Trip photos

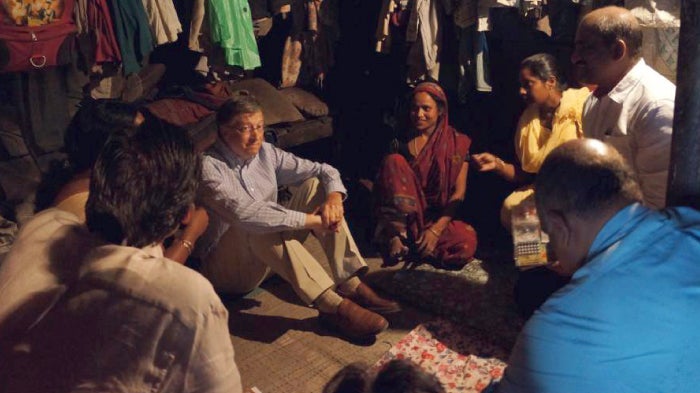

I found inspiration in India

Here are a few pictures from my latest visit to this amazing country.

Around this time last year, I wrote a Gates Notes post that began: “I just returned from my visit to India, and I can’t wait to go back again.”

Last week, I got my wish and returned to India—and now that I’m home, I can’t wait to go back for another visit.

My goal was to get an update on some of the world-changing ideas and inventions that are coming out of India, and that’s exactly what I got. I spent four days there, meeting with political leaders, government officials, scientists, philanthropists, women who are lifting their communities out of poverty, and many others. The Gates Foundation funds more work in India than in any other country (other than the United States), and it’s always uplifting and educational to be there in person and see the impact of the efforts we’re supporting. Here are a few photos from my visit.

The doctor can see you now

Expanding access to health care through AI

Today’s AI can transform health care systems and support health care workers the world over.

A core principle underlying the Gates Foundation’s work is closing the innovation gap between rich countries and everyone else. People in poorer parts of the world shouldn’t have to wait decades for new technologies to reach them. That’s why we've worked for 25 years to accelerate access to life-saving medicines and vaccines in low- and middle-income countries.

It's also why, today, the Gates Foundation and OpenAI are announcing an initiative called Horizon1000 to support several countries in Africa, starting in Rwanda, as they apply AI technology to improve their health care systems.

Over the next few years, we will collaborate with leaders in African countries as they pioneer the deployment of AI in health. Together, the Gates Foundation and OpenAI are committing $50 million in funding, technology, and technical support to back their work. The goal is to reach 1,000 primary healthcare clinics and their surrounding communities by 2028.

Today’s AI can help save lives

A few years ago, I wrote that the rise of artificial intelligence would mark a technological revolution as far-reaching for humanity as microprocessors, PCs, mobile phones, and the Internet. Everything I’ve seen since then confirms my view that we are on the cusp of a breathtaking global transformation.

All over the world, AI, in the form of LLMs and machine learning models, are improving far more quickly than I first anticipated. From science to education to customer service and more, AI tools are reshaping every facet of our lives.

I spend a lot of time thinking about how AI can help us address fundamental challenges like poverty, hunger, and disease. One issue that I keep coming back to is making great health care accessible to all—and that’s why we’re partnering with OpenAI and African leaders and innovators on Horizon1000.

Not enough doctors in the house

We have seen amazing successes in global health over the past 25 years: child mortality has been cut in half, and there are now real pathways to eliminating or controlling deadly diseases like polio, malaria, TB, and HIV. But one stubborn problem that keeps slowing progress is the desperate shortage of health care workers in poorer parts of the world.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, which suffers from the world’s highest child mortality rate, there is a shortfall of nearly 6 million health care workers, a gap so large that even the most aggressive hiring and training efforts can’t close it in the foreseeable future.

These huge shortages put health care workers in these countries in an impossible situation. They’re forced to triage too many patients with too little administrative support, modern technology, and up-to-date clinical guidance. Partly as a result, the WHO estimates that low-quality care is a contributing factor in 6 to 8 million deaths in low- and middle-income countries every year, and that’s not even counting the millions who die because they aren’t able to access health care at all.

Rwanda leads the way

Today’s AI can help save those lives by reaching many more people with much higher-quality care.

Rwanda currently has only one health care worker per 1,000 people, far below the WHO recommendation of about four per 1,000. It would take 180 years for that gap to close at the current pace of progress. So, as part of the 4x4 reform initiative, Minister of Health Dr. Sabin Nsanzimana recently announced the launch of an AI-powered Health Intelligence Center in Kigali to help ensure limited health care resources are being used as wisely as possible.

As part of the Horizon1000 initiative, we aim to accelerate the adoption of AI tools across primary care clinics, within communities, and in people’s homes. These AI tools will support health workers, not replace them.

On the horizon

Minister Nsanzimana has called AI the third major discovery to transform medicine, after vaccines and antibiotics, and I agree with his point of view.

If you live in a wealthier country and have seen a doctor recently, you may have already seen how AI is making life easier for health care workers. Instead of taking notes constantly, they can now spend more time talking directly to you about your health, while AI transcribes and summarizes the visit. Afterwards, AI can handle much of the onerous paperwork, so doctors and nurses can focus on the next patient.

In poorer countries with enormous health worker shortages and lack of health systems infrastructure, AI can be a gamechanger in expanding access to quality care. I believe this partnership with OpenAI, governments, innovators, and health workers in sub-Saharan Africa is a step towards the type of AI we need more of: systems that help people all over the world to solve generational challenges that they simply didn’t know how to address before. I invite others working on AI to think about how we can put these massively powerful tools to the best use.

This announcement is a great example of why I remain optimistic about the improvements we can make. I’m looking forward to seeing health workers using some of these AI solutions in action when I visit Africa, and I plan to continue focusing on ways AI technology can help billions of people in low- and middle-income countries meet their most important needs.

The Year Ahead

Optimism with footnotes

As we start 2026, I am thinking about how the year ahead will set us up for the decades to come.

I have always been an optimist. When I founded Microsoft, I believed a digital revolution powered by great software would make the world a better place. When I started the Gates Foundation, I saw an opportunity to save and improve millions of lives because critical areas like children’s health were getting so little money.

In both cases, the results exceeded my expectations. We are far better off than when I was born 70 years ago. I believe the world will keep improving—but it is harder to see that today than it has been in a long time.

Friends and colleagues often ask me how I stay optimistic in an era with so many challenges and so much polarization. My answer is this: I am still an optimist because I see what innovation accelerated by artificial intelligence will bring. But these days, my optimism comes with footnotes.

The thing I am most upset about is the fact that the world went backwards last year on a key metric of progress: the number of deaths of children under 5 years old. Over the last 25 years, those deaths went down faster than at any other point in history. But in 2025, they went up for the first time this century, from 4.6 million in 2024 to 4.8 million in 2025—an increase driven by less support from rich countries to poor countries. This trend will continue unless we make progress in restoring aid budgets.

The next five years will be difficult as we try to get back on track and work to scale up new lifesaving tools. Yet I remain optimistic about the long-term future. As hard as last year was, I don’t believe we will slide back into the Dark Ages. I believe that, within the next decade, we will not only get the world back on track but enter a new era of unprecedented progress.

The key will be, as always, innovation. Consider this: An HIV diagnosis used to be a death sentence. Today, thanks to revolutionary treatments, a person with HIV can expect to live almost as long as someone without the virus. By the 2040s, new innovations could virtually eliminate deaths from HIV/AIDS.

Budget cuts limit how many people benefit from lifesaving tools, as we saw to devastating effect last year. But nothing can erase the fact that for decades we didn’t know how to save people from HIV, and now we do. Breakthroughs are a bell that cannot be unrung. They ensure that we will never go back to the world in 2000 where over 10 million children died from preventable causes every year—and they form the core of my optimism about where the world is headed.

But as I mentioned, there are footnotes to my optimism. Although the innovation pipeline sets us up for long-term success, the trajectory of progress hinges on how the world addresses three key questions.

1.

Will a world that is getting richer increase its generosity toward those in need?

The “golden rule” precept is more important now than ever with the record disparities in wealth. This idea of treating others as you wish to be treated does not just apply to rich countries giving aid. It must also include philanthropy from the wealthy to help those in need—both domestically and globally—which should grow rapidly in a world with a record number of billionaires and even centibillionaires.

Through the Giving Pledge, I get to work with a number of incredible philanthropists who set a great example by giving away substantial portions of their wealth in smart ways. However, more needs to be done to encourage higher levels of generosity from the rich and to show how fulfilling and impactful it can be.

Turning to aid budgets for poor countries, I am worried about one number: If funding for health decreases by 20 percent, 12 million more children could die by 2045. I know cuts won’t be reversed overnight, even though aid represented less than 1 percent of GDP even in the most generous countries. But it is critical that we restore some of the funding. The foundation’s Goalkeepers report lays out what is at risk and how the world can best spend the aid it gives.

I will spend much of my year working with partners to advocate for increased funding for the health of the world’s children. I plan to engage with a number of communities, including health care workers, religious groups, and members of diaspora communities to help make this case.

2.

Will the world prioritize scaling innovations that improve equality?

Some problems require doing far more than just letting market incentives take their course.

The first critical area is climate change. Without a large global carbon tax (which is, unfortunately, politically unachievable), market forces do not properly incentivize the creation of technologies to reduce climate-related emissions.

Yet only by replacing all emitting activities with cheaper alternatives will we stop the temperature increase. This is why I started Breakthrough Energy 10 years ago and why I will continue to put billions into innovation.

The world has made meaningful progress in the last decade, cutting projected emissions by more than 40 percent. But we still have a lot of innovation and scaling up to do in tough areas like industrial emissions and aviation. Government policies in rich countries are still critical because unless innovations reach scale, the costs won’t come down and we won’t achieve the impact we need.

If we don’t limit climate change, it will join poverty and infectious disease in causing enormous suffering, especially for the world’s poorest people. Since even in the best case the temperature will continue to go up, we also need to innovate to minimize the negative impacts.

This is called climate adaptation, and a critical example is helping farmers in poor countries with better seeds and better advice so they can grow more even in the face of climate change. Using AI, we will soon be able to provide poor farmers with better advice about weather, prices, crop diseases, and soil than even the richest farmers get today. The foundation has committed $1.4 billion to supporting farmers on the frontlines of extreme weather.

I will be investing and giving more than ever to climate work in the years ahead while also continuing to give more to children’s health, the foundation’s top priority. The need to ensure money is spent on the most important priorities was the topic of a memo I wrote in the fall.

A second critical area where the world must focus on innovation-driven equality is health care. Concerns about healthcare costs and quality are higher than ever in all countries.

In theory, people should feel optimistic about the state of health care with the incredible pipeline of innovations. For example, a recent breakthrough in diagnosing Alzheimer’s will revolutionize how we test for—and ultimately prevent—this disease, saving billions of dollars in costs. (Funding Alzheimer’s research is a particular focus for me.) There’s similar progress on obesity and cancer, as well as on problems in developing countries like malaria, TB, and malnutrition.

Despite so much progress, however, the cost and complexity of the system means very few people are satisfied with their care. I believe we can improve health care dramatically in all countries by using AI not only to accelerate the development of innovations but directly in the delivery of health care.

Like many of you, I already use AI to better understand my own health. Just imagine what will be possible as it improves and becomes available for every patient and provider. Always-available, high-quality medical advice will improve medicine by every measure.

We aren’t quite there yet—developers still have work to do on reliability and how we connect the AI to doctors and nurses so they are empowered to check and override the system. But I’m optimistic we will soon begin to scale access globally. I am following this work so the Gates Foundation and partners can make sure this capability is available in the countries that need it most—where there aren’t enough medical personnel—at the same time it is available elsewhere. We are already working on pilots and making sure that even relatively uncommon African languages are fully supported.

Governments will have to play a central role in leading the implementation of AI into their health systems. This is another case where the market alone won’t and can’t provide the solution.

A third and final area I will mention briefly is education. AI gives us a chance for the kind of personalized learning to keep students motivated that we have dreamed of in the past. This is now a focus of the Gates Foundation’s spending on education, and I am hopeful it will be empowering to both teachers and students. I’ve seen this firsthand in New Jersey, and it will be game changing as we scale it for the world.

All three of these areas—climate, health, and education—can improve rapidly with the right government focus. This year I will spend a lot of time meeting with pioneers all over the world to see which countries are doing the best work so we can spread best practices.

3.

Will we minimize negative disruptions caused by AI as it accelerates?

Of all the things humans have ever created, AI will change society the most. It will help solve many of our current problems while also bringing new challenges very different from past innovations.

When people in the AI space predict that AGI or fully humanoid robots will come soon and then those deadlines are missed, it creates the impression that these things will never happen. However, there is no upper limit on how intelligent AIs will get or on how good robots will get, and I believe the advances will not plateau before exceeding human levels.

The two big challenges in the next decade are use of AI by bad actors and disruption to the job market. Both are real risks that we need to do a better job managing. We’ll need to be deliberate about how this technology is developed, governed, and deployed.

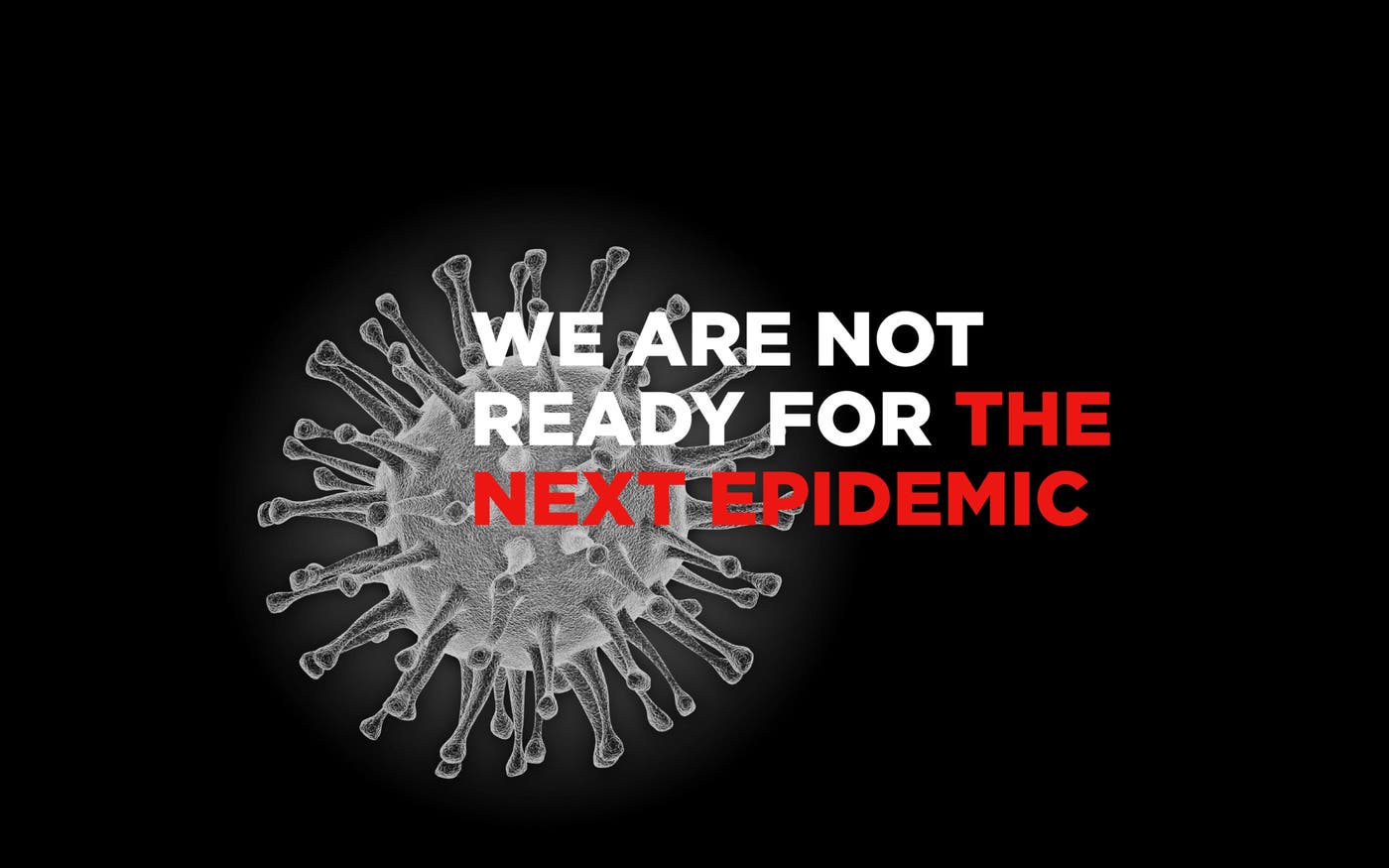

In 2015, I gave a TED talk warning that the world was not ready to handle a pandemic. If we had prepared properly for the Covid pandemic, the amount of human suffering would have been dramatically less. Today, an even greater risk than a naturally caused pandemic is that a non-government group will use open source AI tools to design a bioterrorism weapon.

The second challenge is job market disruption. AI capabilities will allow us to make far more goods and services with less labor. In a mathematical sense, we should be able to allocate these new capabilities in ways that benefit everyone. As AI delivers on its potential, we could reduce the work week or even decide there are some areas we don’t want to use AI in.

The effects of this disruption are hard to model. Sometimes, when a game-changing technology improves rapidly, it drives more demand at lower cost and, by making the world richer, increases demand in other areas. For example, AI makes software developers at least twice as efficient, which makes coding cheaper while also creating demand elasticity for code. (Computing is a good historical example where lower costs actually caused the overall market to grow.)

Even with this complexity, the rate of improvement is already starting to be enough to disrupt job demand in areas like software development. Other areas like warehouse work or phone support are not quite there yet, but once the AIs become more capable, the job disruption will be more immediate.

We’re already starting to see the impact of AI on the job market, and I think this impact will grow over the next five years. Even if the transition takes longer than I expect, we should use 2026 to prepare ourselves for these changes—including which policies will best help spread the wealth and deal with the important role jobs play in our society. Different political parties will likely suggest different approaches.

By including these footnotes, particularly the last one, some readers may find my continued optimism even more surprising. But as we start 2026, I remain optimistic about the days ahead because of two core human capabilities.

The first is our ability to anticipate problems and prepare for them, and therefore ensure that our new discoveries make all of us better off. The second is our capacity to care about each other. Throughout history, you can always find stories of people tending not just to themselves or their clan or their country but to the greater good.

Those two qualities—foresight and care—are what give me hope as the year begins. As long as we keep exercising those abilities, I believe the years ahead can be ones of real progress.

A new way to look at the problem

Three tough truths about climate

What I want everyone at COP30 to know.

There’s a doomsday view of climate change that goes like this:

In a few decades, cataclysmic climate change will decimate civilization. The evidence is all around us—just look at all the heat waves and storms caused by rising global temperatures. Nothing matters more than limiting the rise in temperature.

Fortunately for all of us, this view is wrong. Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Unfortunately, the doomsday outlook is causing much of the climate community to focus too much on near-term emissions goals, and it’s diverting resources from the most effective things we should be doing to improve life in a warming world.

It’s not too late to adopt a different view and adjust our strategies for dealing with climate change. Next month’s global climate summit in Brazil, known as COP30, is an excellent place to begin, especially because the summit’s Brazilian leadership is putting climate adaptation and human development high on the agenda.

This is a chance to refocus on the metric that should count even more than emissions and temperature change: improving lives. Our chief goal should be to prevent suffering, particularly for those in the toughest conditions who live in the world’s poorest countries.

Although climate change will hurt poor people more than anyone else, for the vast majority of them it will not be the only or even the biggest threat to their lives and welfare. The biggest problems are poverty and disease, just as they always have been. Understanding this will let us focus our limited resources on interventions that will have the greatest impact for the most vulnerable people.

I know that some climate advocates will disagree with me, call me a hypocrite because of my own carbon footprint (which I fully offset with legitimate carbon credits), or see this as a sneaky way of arguing that we shouldn’t take climate change seriously.

To be clear: Climate change is a very important problem. It needs to be solved, along with other problems like malaria and malnutrition. Every tenth of a degree of heating that we prevent is hugely beneficial because a stable climate makes it easier to improve people’s lives.

I’ve been learning about warming—and investing billions in innovations to reduce it—for over 20 years. I work with scientists and innovators who are committed to preventing a climate disaster and making cheap, reliable clean energy available to everyone. Ten years ago, some of them joined me in creating Breakthrough Energy, an investment platform whose sole purpose is to accelerate clean energy innovation and deployment. We’ve supported more than 150 companies so far, many of which have blossomed into major businesses. We’re helping build a growing ecosystem of thousands of innovators working on every aspect of the problem.

My views on climate change are also informed by my work at the Gates Foundation over the past 25 years. The foundation’s top priority is health and development in poor countries, and we approach climate largely through that lens. This has led us to fund a lot of climate-smart innovations, especially in agriculture, in places where extreme weather is taking the worst toll.

COP30 is taking place at a time when it’s especially important to get the most value out of every dollar spent on helping the poorest. The pool of money available to help them—which was already less than 1 percent of rich countries’ budgets at its highest level—is shrinking as rich countries cut their aid budgets and low-income countries are burdened by debt. Even proven efforts like providing lifesaving vaccines for all the world’s children are not being fully funded. Gavi (the vaccine-buying fund) will have 25 percent less money for the next five years compared to the past five years. We have to think rigorously and numerically about how to put the time and money we do have to the best use.

So I urge everyone at COP30 to ask: How do we make sure aid spending is delivering the greatest possible impact for the most vulnerable people? Is the money designated for climate being spent on the right things?

I believe the answer is no.

Sometimes the world acts as if any effort to fight climate change is as worthwhile as any other. As a result, less-effective projects are diverting money and attention from efforts that will have more impact on the human condition: namely, making it affordable to eliminate all greenhouse gas emissions and reducing extreme poverty with improvements in agriculture and health.

In short, climate change, disease, and poverty are all major problems. We should deal with them in proportion to the suffering they cause. And we should use data to maximize the impact of every action we take.

I believe that embracing the following three truths will help us do that.

Even if the world takes only moderate action to curb climate change, the current consensus is that by 2100 the Earth’s average temperature will probably be between 2°C and 3°C higher than it was in 1850.

That’s well above the 1.5°C goal that countries committed to at the Paris COP in 2015. In fact, between now and 2040, we are going to fall far short of the world’s climate goals. One reason is that the world’s demand for energy is going up—more than doubling by 2050.

From the standpoint of improving lives, using more energy is a good thing, because it’s so closely correlated with economic growth. This chart shows countries’ energy use and their income. More energy use is a key part of prosperity.

Unfortunately, in this case, what’s good for prosperity is bad for the environment. Although wind and solar have gotten cheaper and better, we don’t yet have all the tools we need to meet the growing demand for energy without increasing carbon emissions.

But we will have the tools we need if we focus on innovation. With the right investments and policies in place, over the next ten years we will have new affordable zero-carbon technologies ready to roll out at scale. Add in the impact of the tools we already have, and by the middle of this century emissions will be lower and the gap between poor countries and rich countries will be greatly reduced.

I wasn’t sure this would be possible when Breakthrough Energy was started in 2015 after the Paris agreement. Since then, the progress of Breakthrough companies and others and the acceleration now being provided by the use of artificial intelligence have made me confident that these advances will be ready to scale.

All countries will be able to construct buildings with low-carbon cement and steel. Almost all new cars will be electric. Farms will be more productive and less destructive, using fertilizer created without generating any emissions. Power grids will deliver clean electricity reliably, and energy costs will go down.

Even with these innovations, though, the cumulative emissions will cause warming and many people will be affected. We’ll see what you might call latitude creep: In North America, for instance, Iowa will start to feel more like Texas. Texas will start to feel more like northern Mexico. Although there will be climate migration, most people in countries near the equator won’t be able to relocate—they will experience more heat waves, stronger storms, and bigger fires. Some outdoor work will need to pause during the hottest hours of the day, and governments will have to invest in cooling centers and better early warning systems for extreme heat and weather events.

Every time governments rebuild, whether it’s homes in Los Angeles or highways in Delhi, they’ll have to build smarter: fire-resistant materials, rooftop sprinklers, better land management to keep flames from spreading, and infrastructure designed to withstand harsh winds and heavy rainfall. It won’t be cheap, but it will be possible in most cases. Unfortunately, this capacity to adapt is not evenly distributed, a subject I will return to below.

So why am I optimistic that innovation will curb climate change? For one thing, because it already has.

You probably know about improvements like better electric vehicles, dramatically cheaper solar and wind power, and batteries to store electricity from renewables. What you may not be aware of is the large impact these advances are having on emissions.

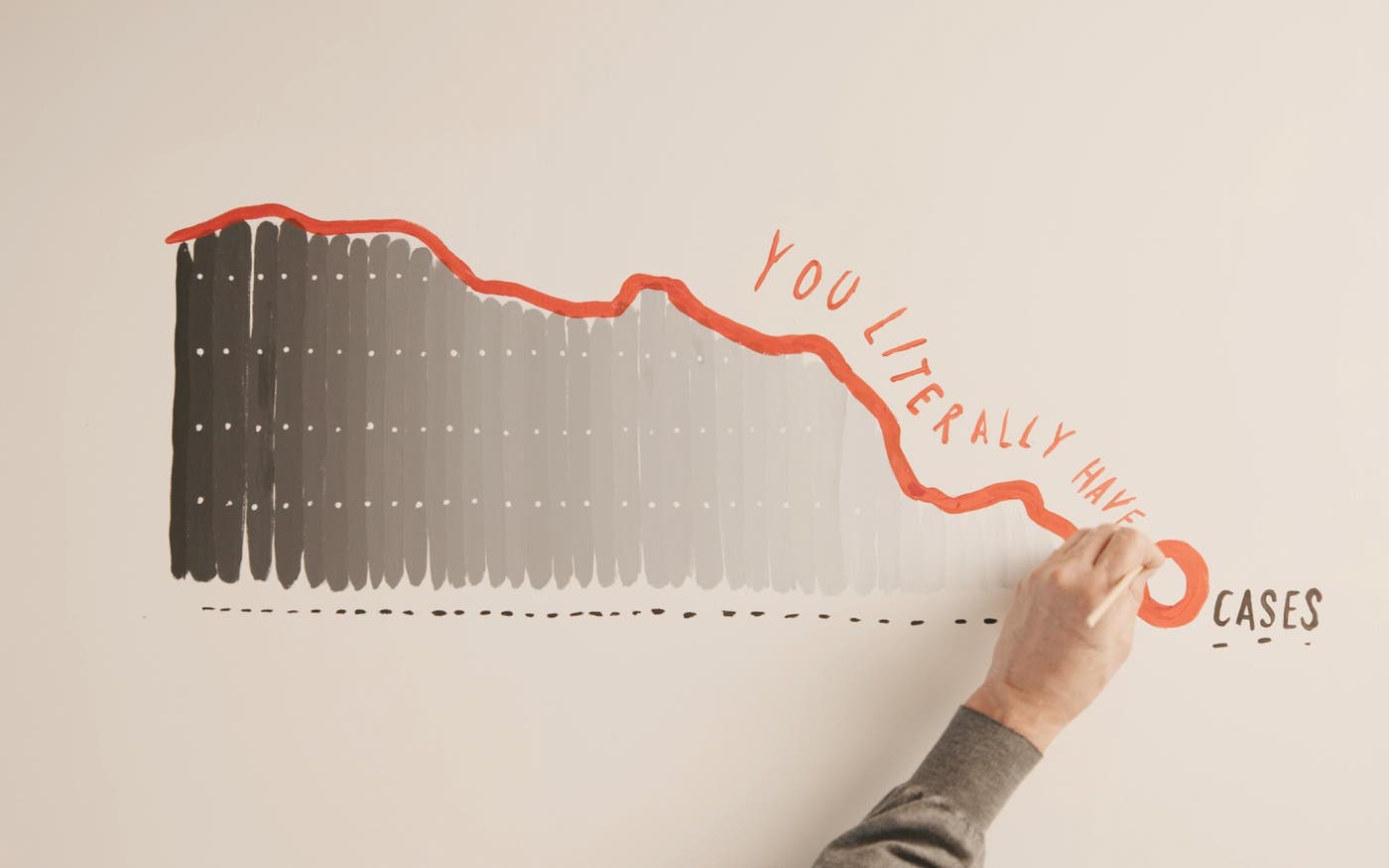

Ten years ago, the International Energy Agency predicted that by 2040, the world would be emitting 50 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year. Now, just a decade later, the IEA’s forecast has dropped to 30 billion, and it’s projecting that 2050 emissions will be even lower.

Read that again: In the past 10 years, we’ve cut projected emissions by more than 40 percent.

This progress is not part of the prevailing view of climate change, but it should be. What made it possible is that the Green Premium—the cost difference between clean and dirty ways of doing something—reached zero or became negative for solar, wind, power storage, and electric vehicles. By and large, they are just as cheap as, or even cheaper than, their fossil fuel counterparts.

Of course, to get to net zero, we need more breakthroughs. This will become even more important if new evidence shows that climate change will be much worse than what the current generation of climate models predicts, because we will need to lower the Green Premium faster and accelerate the transition to a zero-emission economy.

Luckily, humans’ ability to invent is better than it has ever been.

Breakthrough Energy focuses its new investment on the areas of innovation that still have large positive Green Premiums. Below I write about the state of play in the five sectors of the economy that are responsible for all carbon emissions. I’ll cover highlights and challenges—one common theme will be the difficulty of scaling rapidly—and I’ll include some of the companies Breakthrough Energy works with so you can see how much activity there is in each sector.

Electricity (28 percent of global emissions)

Making electricity is the second biggest source of emissions, but it’s arguably the most important: To decarbonize the other sectors, we’ll have to electrify a lot of things that currently use fossil fuels. We need more innovation in renewables, transmission, and other ways to generate and store electricity.

- New approaches to wind power can generate more energy using less land, and advances in geothermal mean it’s being tapped in more places around the world. (Examples: Fervo, Baseload Capital, Airloom)

- Companies are pilot-testing highly efficient power lines that can transmit much more electricity than the previous generation of cables. (TS Conductor, VEIR)

- We need to keep reducing the cost of clean energy that’s available around the clock, including new nuclear fission and fusion facilities. More than half of today’s emissions from electricity could only be eliminated using these so-called “firm” sources, but they have a Green Premium of well over 50 percent. I’m hopeful that we can get rid of the Green Premium with fission; a next-generation nuclear power plant is under construction in Wyoming. And fusion, which promises to give us an inexhaustible supply of cheap clean electricity, has moved from science fiction to near-commercial. (TerraPower, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, Type One Energy)

Manufacturing (30 percent of global emissions)

When someone tells you they know how to curb emissions, the first question you should ask is: What’s your plan for cement and steel? They’re key to modern life, and they’re hard to decarbonize on a global scale because it’s so cheap to make them with fossil fuels.

- Zero-emissions steel exists today. It’s made using electricity, so if you can get clean electricity that’s cheap enough, you end up with clean steel that’s cheaper than the conventional type. The technology still needs to get into more markets, and companies that make clean steel need to expand their capacity. (Boston Metal, Electra)

- Clean cement faces similar hurdles. Several companies have found ways to make it with no Green Premium, but it takes years to get a foothold in the global market and ramp up manufacturing capacity. (Brimstone, Ecocem, CarbonCure, Terra CO2, Fortera)

- One of the biggest energy surprises of the past decade is the discovery of geologic hydrogen. Eventually, hydrogen will be widely used to make clean fuels and will help with clean steel and cement. Today we make it from fossil fuels or by running electricity through water, but geologic hydrogen is generated by the Earth itself. Companies have already proven that they can find it underground; now the challenge is to extract it efficiently. There’s also been a lot of progress on making hydrogen with electricity much more cheaply than current technology does it. (Koloma, Mantle8, Electric Hydrogen)

- Companies are beginning to roll out ways to either capture carbon from facilities that currently emit it, such as cement and steel plants, or to remove it directly from the air and store it permanently. If captured carbon becomes cheap enough, we could even use it to make things like sustainable aviation fuel. (Heirloom, Graphyte, MissionZero, Deep Sky)

Agriculture (19 percent of global emissions)

Much of the emissions from agriculture comes from just two sources: the production and use of fertilizer, and grazing livestock that release methane.

- Farmers can already buy one replacement for synthetic fertilizer that’s made without any emissions, and another that turns the methane in manure into organic fertilizer. Both are selling at a negative Green Premium. Now the challenge is to produce them in large quantities and persuade farmers to use them. (Pivot Bio, Windfall Bio)

- Additives to cattle feed that keep livestock from producing methane are nearly cheap enough to be economical for farmers, and a vaccine that does the same thing has been shown to work. It’s now moving into the next stage of development. (Rumin8, ArkeaBio)

- Another source of methane is the cultivation of rice, one of the world’s most important staple foods. Companies are helping rice farmers around the world adopt new methods that both reduce methane emissions and increase crop yields. (Rize)

- One stubborn problem is that some of the nitrogen in fertilizer seeps into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. It’s very dilute, which makes it hard to capture.

Transportation (16 percent of global emissions)

Nearly one in four cars sold in 2024 was an EV, and more than 10 percent of all vehicles in the world are electric. In some countries including the U.S., they still have disadvantages, such as long charging times and too few public charging stations, that keep them from being as practical as gas-powered cars. In addition, cars and trucks are just one part of this sector, which also includes tough-to-decarbonize activities like shipping and aviation.

- Airplane emissions are projected to double by 2050, and clean jet fuel still comes with a Green Premium of over 100 percent. Today we know of only two cost-effective ways to make it: produce it with algae, or make synthetic fuel using very cheap hydrogen. Companies are in the early stages of work on both approaches.

- As more transportation goes electric, the demand for batteries is going to increase, which is why companies have developed ways to make them cheaper and more efficient. (KoBold Metals, GeologicAI, Redwood, Stratus Materials)

Buildings (7 percent of global emissions)

Heating and cooling buildings is the smallest slice of global emissions today, but it’s going to skyrocket with urbanization and the growing need for air conditioning.

- Electric heat pumps are widely available, up to five times more efficient than boilers and furnaces, and often the cheaper option. But there aren’t enough skilled workers around the world to install them. Next-generation, extra-efficient heat pumps are already on the market, and ones that are easier to install are in the works. (Dandelion, Blue Frontier, Conduit Tech)

- Other zero Green Premium products are available, including building sealants and super-efficient windows. But as with so many clean technologies, reaching scale takes time. (Aeroseal, Luxwall)

The global temperature doesn’t tell us anything about the quality of people’s lives. If droughts kill your crops, can you still afford food? When there’s an extreme heat wave, can you go somewhere with air conditioning? When a flood causes a disease outbreak, can the local health clinic treat everyone who’s sick?

Quality of life may seem like a vague concept, but it’s not. One useful tool for measuring it is the United Nations’ Human Development Index, which provides a snapshot of how people in a country are faring—from 0 to 1, with higher numbers meaning better outcomes.

If you look through a list of the HDI scores of the world’s countries, the disparities leap out at you. Switzerland has the highest HDI, at 0.96. South Sudan, the lowest, is at 0.33. The 30 countries with the lowest HDI scores are home to one out of every eight people on the planet, but they produce only about one third of 1 percent of global GDP. They have the highest poverty rates and, tragically, the worst health outcomes. A child born in South Sudan is 39 times more likely to die before her fifth birthday than one born in Sweden.

This inequity is the reason our climate strategies need to prioritize human welfare. This may seem obvious—who could be against improving people’s lives?—but sometimes human welfare takes a backseat to lowering emissions, with bad consequences.

For example, a few years ago, the government of one low-income country set out to cut emissions by banning synthetic fertilizers. Farmers’ yields plummeted, there was much less food available, and prices skyrocketed. The country was hit by a crisis because the government valued reducing emissions above other important things.

Sometimes the pressure comes from outsiders. For example, multilateral lenders have been pushed by wealthy shareholders to stop financing fossil fuel projects, with the hope of limiting emissions by leaving oil, gas, and coal in the ground. This pressure has had almost no impact on global emissions, but it has made it harder for low-income countries to get low-interest loans for power plants that would bring reliable electricity to their homes, schools, and health clinics.

Granted, situations like these are complicated, since burning fossil fuels helps people now at the cost of making the climate worse for people in the future. But remember that climate change is not the biggest threat to the lives and livelihoods of people in poor countries, and it won’t be in the future. In the next section, I’ll explain why and what it means for our climate strategies.

A few years ago, researchers at the University of Chicago’s Climate Impact Lab ran a thought experiment: What happens to the number of projected deaths from climate change when you account for the expected economic growth of low-income countries over the rest of this century? The answer: It falls by more than 50 percent.

This finding is exciting because it suggests a way forward. Since the economic growth that’s projected for poor countries will reduce climate deaths by half, it follows that faster and more expansive growth will reduce deaths by even more. And economic growth is closely tied to public health. So the faster people become prosperous and healthy, the more lives we can save.

When you look at the problem this way, it becomes easier to find the best buys in climate adaptation—they’re the areas where finance can do the most to fight poverty and boost health.

At the top of that list is improvements in agriculture.

Most poor countries are still largely agrarian economies. The average smallholder farmer in these countries has between two and four acres and makes about $2 a day. And she gets relatively little from her fields, about 80 percent less per acre than an American farmer. A single drought or flood can wipe her out for an entire season.

Lower emissions will eventually lead to fewer devastating losses, but today’s farmers don’t have time to wait for the climate to stabilize. They need to raise their incomes and feed their families now.

Mobile phones are already making a dramatic difference. Farmers use their phones to get advice on what to plant, when to plant, and when to fertilize that’s tailored by artificial intelligence to account for their soil, weather, and other local conditions. In India, during the most recent summer monsoon, around 40 million farmers in 13 states received an advance warning by SMS that the rains would arrive early and then pause. That single message saved millions of acres of crops.

And the technology is improving rapidly: In the next five years, a low-income farmer will be able to get better advice than anything that’s available to the richest farmers today.

Advances in crop breeding are another great buy, and Kenya has set an excellent example. Nearly 20 years ago, a group of African agricultural scientists saw that hotter, drier seasons were putting staple crops like maize under stress. So with support from the Gates Foundation and others, they developed a variety that could thrive in a changing climate. It worked: The new seeds gave a group of Kenyan farmers 66 percent more maize, enough to feed a family of six for a year and still have $880 worth of crops left over to sell. That’s equivalent to five months of income for them.

The list of innovations goes on. For example, researchers have helped farmers identify breeds of cattle that are naturally more resilient in tough conditions. And the new class of natural zero-emissions fertilizers I mentioned earlier is being tailored to the conditions in low-income countries. Scientists at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in India found that when smallholder farmers added these biofertilizers to their fields, their yields went up as much as 20 percent.

Improvements like these need to go hand in hand with improvements in health. I think if you ask most people how they think climate will affect health, they’ll talk about heat waves and natural disasters. So let’s start there and look at the facts.

Excessively hot weather now causes around 500,000 deaths every year. Despite the impression you’d get from the news, though, the number has been decreasing for some time, chiefly because more people can afford air conditioners. And, surprisingly, excessive cold is far deadlier, killing nearly ten times more people every year than heat does. As for what will happen in the future, heat deaths will go up and cold deaths will go down. The best current estimates suggest that the net effect will be a global rise in temperature-related mortality, and that most of the increase will be in developing countries.

The story so far with natural disasters is similar. In the past century, direct deaths from natural disasters, such as drowning during a flood, have fallen 90 percent to between 40,000 and 50,000 people a year, thanks mostly to better warning systems and more-resilient buildings.

But indirect deaths from natural disasters have not followed the same pattern of decline. In most cases today, people caught in storms and floods are more likely to die from a waterborne disease than from drowning. When floodwaters contaminate drinking water, they create ideal breeding grounds for cholera and rotavirus, which cause diarrhea and are especially deadly for children. More floods equals more diarrheal deaths.

But pathogens don’t wait around for storms or floods to infect people. Diarrheal diseases kill more than a million people a year, and the vast majority of infections don’t happen in a sudden tragic flash. They’re part of life in a low-income country. And, sadly, they’re not the only ongoing health threat.

If you include the other major causes of death in poor countries—malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS, respiratory infections, and complications from childbirth—poverty-related health problems kill about 8 million people a year.

And the burden is even worse when you factor in the health problems that don’t kill people but make them too sick to work, go to school, or take care of their kids. If a pregnant woman is already malnourished and then has her food supply cut off because of a flood, she’s even more likely to give birth prematurely, and her baby is more likely to start life underweight. But if she’s well-nourished to begin with, she and her baby have a much better chance to stay healthy.

I’m not saying we should ignore temperature-related deaths because diseases are a bigger problem. In fact, temperature-related deaths are one of the reasons why cheap clean energy is so important—it will make heating and air conditioning more affordable everywhere.

What I am saying is that we should deal with disease and extreme weather in proportion to the suffering they cause, and that we should go after the underlying conditions that leave people vulnerable to them. While we need to limit the number of extremely hot and cold days, we also need to make sure that fewer people live in poverty and poor health so that extreme weather isn’t such a threat to them.

Artificial intelligence has already begun to help do that. Today, for example, AI-powered devices make it possible for health workers to provide ultrasound exams for pregnant women in low-income settings—a breakthrough that means many more women will get the treatment they need to survive childbirth and deliver a healthy baby. AI is also helping researchers develop new vaccines and treatments faster, adding to the long list of affordable lifesaving tools that are already available, including vaccines, biofortified foods, bed nets, and treatments for diseases like AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis.

The benefits of improving health and agriculture go beyond climate resilience. For example, as child survival rates go up, something unexpected takes place: People choose to have smaller families. When this happens, governments of poor countries can invest more in schools and health clinics, roads and ports, and sanitation systems and power grids. These things in turn make it easier to improve health and raise incomes. It is a remarkable virtuous cycle and it is set in motion by better health and agriculture.

In this memo, I’ve argued that we should measure success by our impact on human welfare more than our impact on the global temperature, and that our success relies on putting energy, health, and agriculture at the center of our strategies.

Development doesn’t depend on helping people adapt to a warmer climate—development is adaptation.

Under Brazil’s leadership, adaptation and human development will get more attention at COP30 than at any other COP. That’s a promising first step.

For COP30 and beyond, I see two priorities that I hope the climate community will embrace.

1.

Drive the Green Premium to zero.

At each COP, governments take turns announcing commitments to lower their emissions. Unfortunately, this process doesn’t tell us which technologies are needed to meet those commitments, whether we have them yet, or what it will take to get them.

This is why, in addition to country-by-country commitments, every COP should have high-level discussions and commitments based on the five sectors. Policies and innovations in each sector need to get more visibility. Representatives from each of the five sectors should report on progress toward affordable and practical zero-carbon innovations, using the Green Premium as their yardstick.

Government leaders would get a view into whether they can meet their commitments with existing tools. They would see, sector by sector, which technologies they can start adopting now, which ones they should plan to roll out soon, and which ones still need government action to reduce the Green Premium. They would talk to their peers from other countries about working together on promising breakthroughs that will help everyone meet their commitments.

If you’re a policymaker, you can bring this sector-by-sector focus on the Green Premium to your government’s work. You can also protect funding for clean technologies and the policies that promote them. This is not just a public good: The countries that win the race to develop these breakthroughs will create jobs, hold enormous economic power for decades to come, and become more energy independent.

If you’re an activist, you can call for steps that make clean alternatives in every sector as cheap and practical as their fossil fuel counterparts. The public is more likely to switch to clean technology when it’s cheaper and better than fossil fuels.

If you’re a young scientist or entrepreneur, this is a moment to rethink what it means to change the world. The people working on clean materials today will have an enormous impact on human welfare. If you need pointers, the Climate Tech Map published last month by Breakthrough Energy and other partners is an excellent guide to the technologies that are essential for decarbonizing the economy.

If you’re an investor, I encourage you to invest in companies working on high-impact clean technologies that will eventually have no Green Premium. I’m putting more of my own money into these efforts because reducing the Green Premium to zero demands more for-profit capital. It’s also a fantastic investment in what will be the biggest growth industry of the 21st century. (I will give any profits I make from my investments to the Gates Foundation.)

2.

Be rigorous about measuring impact.

I wish there were enough money to fund every good climate change idea. Unfortunately, there isn’t, and we have to make tradeoffs so we can deliver the most benefit with limited resources. In these circumstances, our choices should be guided by data-based analysis that identifies ways to deliver the highest return for human welfare.

Vaccines are the undisputed champion of lives saved per dollar spent. Since 2000, Gavi has spent $22 billion to immunize children in poor countries, preventing 19 million deaths. That means Gavi can save a life for a little more than $1,000. Other estimates find that vaccines cost less than $5,000 per life saved. And vaccines become even more important in a warming world because children who aren’t dying of measles or whooping cough will be more likely to survive when a heat wave hits or a drought threatens the local food supply.

Every effort in the world’s climate agenda should undergo a similar analysis and be prioritized by its ability to save and improve lives cost-effectively. Malaria prevention, for example, is nearly as good as vaccines on the basis of cost per life saved. Energy innovation is a good buy not because it saves lives now, but because it will provide cheap clean energy and eventually lower emissions, which will have large benefits for human welfare in the future. Many of the best buys in agricultural innovation will be on display at COP30 in a showcase hosted by the Gates Foundation, the Brazilian government, and other partners.

This moment reminds me of another time when I called for a new direction.

Thirty years ago, when I was running Microsoft, I wrote a long memo to employees about a major strategic pivot we had to make: embracing the internet in every product we made.

It seems like an obvious move now, given that online activity is such an integral part of everyone’s life, but at the time, the internet was just entering the mainstream. If we hadn’t adjusted our strategy, our success would have been at risk.

For a company, it's relatively easy to make a shift like that because there’s only one person in charge. By contrast, there is no CEO who sets the world’s climate priorities or strategies, which is exactly as it should be. These are rightly determined by the global climate community.

So I urge that community, at COP30 and beyond, to make a strategic pivot: prioritize the things that have the greatest impact on human welfare. It’s the best way to ensure that everyone gets a chance to live a healthy and productive life no matter where they’re born, and no matter what kind of climate they’re born into.

Life and death

How to cut child mortality in half… again

We already know how to save millions of newborn lives.

When Paul Allen and I started Microsoft, we had an ambitious goal: to put a computer on every desk and in every home. A lot of people thought we were out of our minds. But we believed in the power and potential of these machines to change the world. So every day, we came to work determined to make it happen. Now, it’s hard to imagine the world any other way. In a few short decades, that goal became reality for billions.

In 1990, the possibility that the world would be able to cut child mortality in half over the next thirty years would have seemed just as remote. But that’s exactly what happened. And I believe the world can do it again by 2040—we can cut child mortality in half once more—and get even closer to ending all preventable child deaths.

My introduction to this issue came 27 years ago, when I read a piece in The New York Times about deadly drinking water in the world’s poorest countries that contained the following statistic: “Diarrhea kills some 3.1 million people annually, almost all of them children.” Learning that shocked me to my core. There’s no greater pain than the death of a child. The death of millions of them—from something easily treatable in much of the world—is tragedy after tragedy on an almost unfathomable scale.

Before long, I was learning everything I could about global health generally and child mortality specifically. And shortly after, the Gates Foundation, which was just getting off the ground, made it our mission to fight preventable health disparities like this around the world—with an emphasis on children whose lives were being cut short before they ever had a chance.

My look ahead

What it takes to take a breath

New tools can help millions more newborns—and their mothers—survive.

In a rural health clinic, a baby tries to take her first breath.

But her lungs aren’t ready. Because she was born too early, they haven’t developed the slick, soap-like substance that keeps her air sacs from collapsing. Without that substance—called lung surfactant—breathing becomes a desperate, exhausting act.

She’s suffering from respiratory distress syndrome, or RDS, a life-threatening condition that appears within hours of birth in premature babies. Unless she gets treatment, her oxygen levels will plummet and her organs will begin to shut down. In one study from India, every baby born with RDS outside of a hospital setting died. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, RDS is responsible for almost half of all neonatal deaths.

At hospitals in higher-income countries, there’s a way to save her: a liquid form of organically-derived surfactant delivered directly into the lungs. But the procedure requires a highly-trained specialist to guide a breathing tube down the newborn’s windpipe—avoiding the stomach and placing it just right—at a cost of up to $20,000. In many parts of the world, that kind of care simply doesn’t exist.

But what if any healthcare worker anywhere in the world could simply hold a small nebulizer to the baby's face and deliver surfactant as an easy-to-administer inhalant?

This breakthrough—a synthetic surfactant that’s stable enough to be delivered through a nebulizer—is still in development, drive in part by Gates Foundation-supported research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, and The Lundquist Institute. But its promise is extraordinary: an RDS treatment that costs less to make, doesn’t require a specialist to administer, and eliminates the need for intubation.

In other words, a therapy currently limited to the most advanced hospitals could become accessible in rural clinics and community settings around the world. Even in places with top-tier care, it could make treatment gentler, faster, and easier to deliver. In the United States—where RDS still affects 24,000 newborns a year—it could reduce the risks that come with intubating babies who might weigh only two or three pounds.

It’s the kind of innovation that could help solve one of the most persistent problems in global health: delivering intensive care without an intensive care unit, and helping millions more babies survive their first, most fragile moments.

Since 1990, the mortality rate for children under five has been cut by more than half—an amazing mark of global progress. But another statistic hasn’t fallen as fast: the number of babies who die in their first month of life.

Each year, 2.3 million newborns don’t survive past their first 28 days. And the day a baby is born is the most dangerous day of their life. The single biggest cause of these deaths is prematurity. Nearly 900,000 babies a year die from complications related to being born too soon, including infection, underdeveloped organs, and RDS.

Lower cost, easier-to-deliver surfactant is one way to give newborns a fighting chance, but it’s not the only way. Around the world, simple, affordable interventions already exist to identify at-risk pregnancies earlier, prevent more preterm births, and ensure a healthy birthing experience for mothers. Not only are these tools designed to work in the hardest-to-reach places—many of them start working even before a baby takes that first breath.

One of these innovations is a new type of ultrasound that’s changing who can catch the risks of preterm birth—and where.

Around the world, two thirds of women never get an ultrasound screening during pregnancy. Traditional machines are bulky and expensive, with specialized training required to operate them and interpret their results. In places where medical resources are already stretched thin, these types of ultrasounds are rarely an option.

But now, we have ultrasound devices about the size of a phone that can be operated by a nurse or midwife—no on-site specialist required. They weigh less than a pound. They process scans instantly. Their AI interface automatically detects high-risk conditions, like a shortened cervix or signs of early labor, so patients are referred for further care. And they have built-in telehealth functions to share images with remote specialists when needed.

By finding and flagging risks early, these AI-enabled ultrasounds are giving healthcare workers more time to act. In some cases, that means transferring the mother to a higher-level facility. In others, it means providing her with antenatal steroids—an inexpensive, underused treatment that speeds up fetal lung development—and, when needed, medications that delay labor just long enough for those steroids to take effect.

Early warning is essential, but we can save even more lives by going further upstream, starting with the health of pregnant women themselves.

In many low-income countries, undernutrition isn’t an exception. It’s the norm. And the intense demands of pregnancy make nutritional deficiencies even worse—putting mothers at increased risk of complications or death in childbirth, and raising the odds of early labor, low birth weight, and developmental delays for their babies.

But there’s a surprisingly simple fix: a daily supplement called MMS, or multiple-micronutrient supplementation, developed by the United Nations. It contains 15 essential vitamins and minerals for pregnancy—like zinc to reduce the risk of early labor, folic acid to help prevent birth defects, iron and vitamin D for healthy birth weight, and iodine for brain development. For an entire pregnancy, it costs just $2.60.

If MMS became the standard prenatal supplement in every low- and middle-income country, it could save nearly half a million newborn lives each year—and prevent serious complications in 25 million births by 2040.

The innovations above focus on treating, detecting, and preventing premature birth, a huge threat to newborn survival. But one of the most powerful ways to protect babies, preterm or full-term, is by ensuring their mothers stay healthy through pregnancy and childbirth.

When a woman dies during delivery, her baby is 46 times more likely to die in that first month of life. That’s why any serious effort to tackle infant mortality must also address postpartum hemorrhage—which tragically kills 70,000 women a year and is the leading cause of maternal mortality. Fortunately, two innovations are already helping healthcare workers catch and treat it before it becomes fatal.

The first is a calibrated drape—a simple plastic sheet placed under a woman during delivery that collects blood and shows, through printed measurement lines, exactly how much she’s losing. It gives healthcare workers a fast, accurate way to spot dangerous bleeding before it becomes life-threatening. The second is a one-time, 15-minute iron infusion during pregnancy that treats severe anemia—so if a woman does hemorrhage during childbirth, she’s less likely to experience catastrophic blood loss and more likely to survive.

Neither of these tools is complicated or expensive. But in combination, they can make a life-or-death difference for mothers and the babies who depend on them.

Taken together, these innovations form a chain of survival. They help mothers stay healthy through pregnancy. They detect problems before they become emergencies. They give fragile newborns a fighting chance. And they make it possible for families to celebrate a baby’s birth rather than mourning a loss.

Some of these tools are already saving lives. Others are on the verge of doing so. But their impact will be limited unless we prioritize and fund their delivery, not just their development. The world needs to make sure these innovations don’t get stuck in labs or warehouses—so they can reach the mothers and babies who need them most.

My look back

The breakthrough that transformed the Gates Foundation

This is the story of how better data helped us cut child mortality in half.

We started the Gates Foundation 25 years ago to save and improve children’s lives. But no one can solve a problem they don’t fully understand. And back in 2000, the world’s understanding of childhood mortality was occasionally inaccurate, often imprecise, and almost always incomplete.

That’s why I believe the breakthrough that transformed our foundation in the two-and-a-half decades since wasn’t a single vaccine or treatment—it was a revolution in the world’s understanding of childhood mortality. Through advances in how researchers collect and analyze global health data, we now know much more about what kills children, where these deaths occur, and why some kids are more vulnerable than others. By putting those insights to work, we’ve been able to save lives.

The first challenge was knowing exactly what was killing children.

Reading the 1993 World Development Report opened my eyes to the scale of the problem: Around 12 million children under the age of five were dying every year, with a staggering disparity between rich and poor countries. But the available data was fragmented and inconsistent. That made it difficult to understand trends or allocate resources effectively.

So the foundation helped create the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, to give a permanent home to the Global Burden of Disease study—originally developed in the 1990s by researchers at Harvard University and the World Health Organization. We wanted to expand it from a static snapshot of the problem into a regularly updated tool that tracked how diseases impact people around the world. That gave us something the world never had before: a comprehensive—and current—picture of child mortality across every country.

Measuring symptom-based causes of children’s deaths was an important step. But broad disease categories like “diarrhea” or “respiratory infection” didn’t give us enough information to act on. We needed to know which specific pathogens were responsible for the most common and fatal cases. So the Gates Foundation funded two landmark studies to find out.

In 2013, the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, or GEMS, found that rotavirus was causing 20 percent of lethal diarrhea cases in kids. At the time, diarrhea was the second-leading infectious killer of children. While oral rehydration therapy had already helped bring down deaths over previous decades, GEMS helped fast-track the rollout of a more targeted tool—a new rotavirus vaccine—in the hardest-hit countries, in close partnership with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

A year later, the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study, or PERCH, revealed that respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, was a much more common cause of severe pneumonia—the leading infectious killer of kids around the world—than previously understood. (And not just in low- and middle-income countries, where 97 percent of RSV deaths occur, but in higher-income ones too, where the virus still fills pediatric hospital wards each winter.) That prompted us to expand our investments in RSV prevention, which led to the approval of the first maternal vaccines for RSV in 2023.

But understanding what causes childhood mortality wasn’t enough on its own, because deaths aren’t distributed evenly across countries—or even within them. That’s why our second challenge was to figure out where exactly children were dying.

At the time, most health data was collected at national or regional levels. That masked major differences in disease burden from one community to the next—and made it harder to target interventions effectively.

To solve this second challenge, the foundation invested in new approaches to health mapping that combined satellite imagery, GIS technology, GPS data, and local health surveys. These maps gave Ministries of Health and implementing partners unprecedented, anonymized detail about disease patterns and population distribution, down to individual neighborhoods, that transformed how and where public health resources are deployed—while still preserving the privacy of the individual children and families in these places.

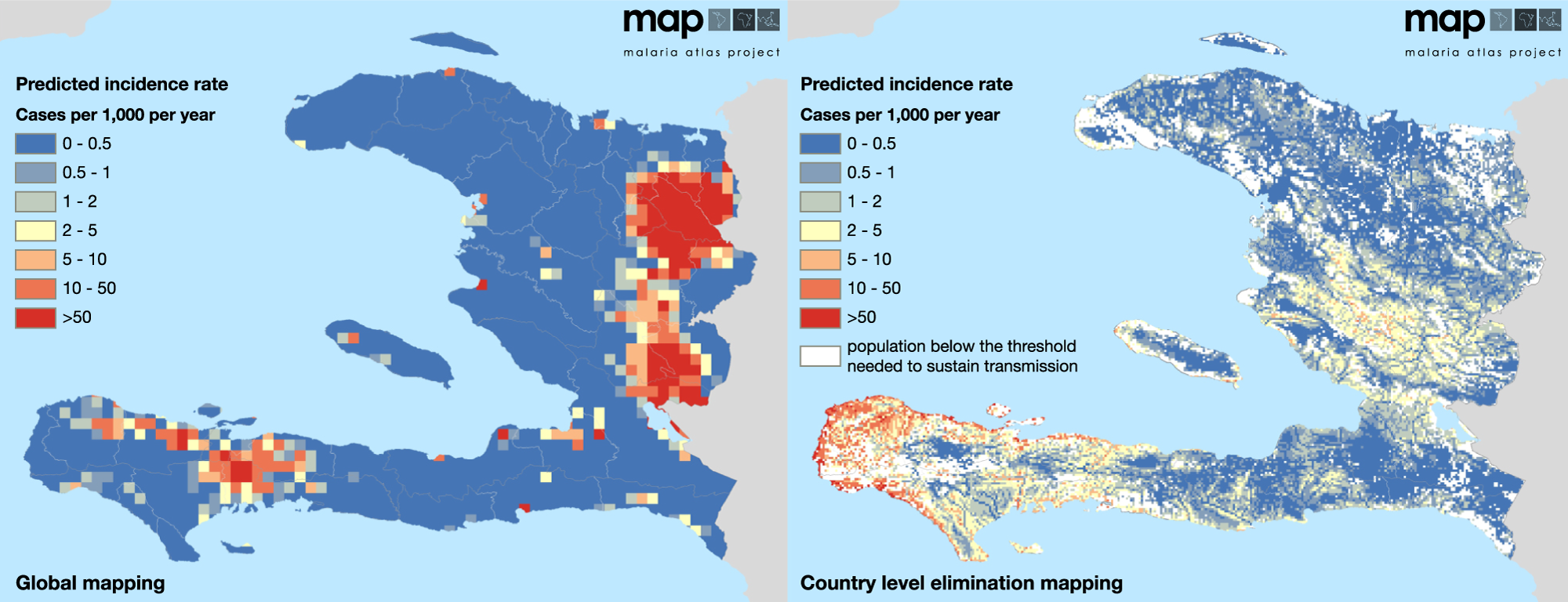

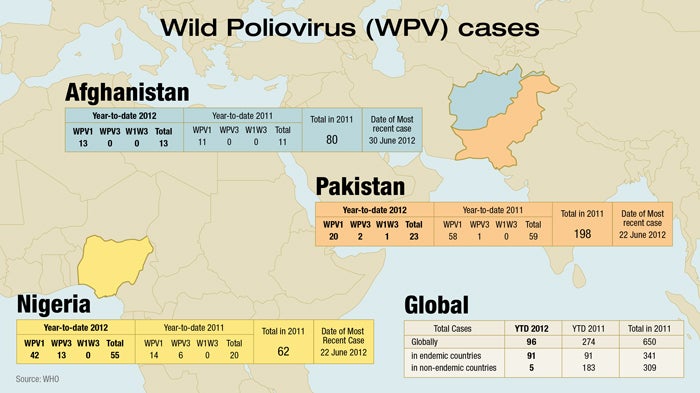

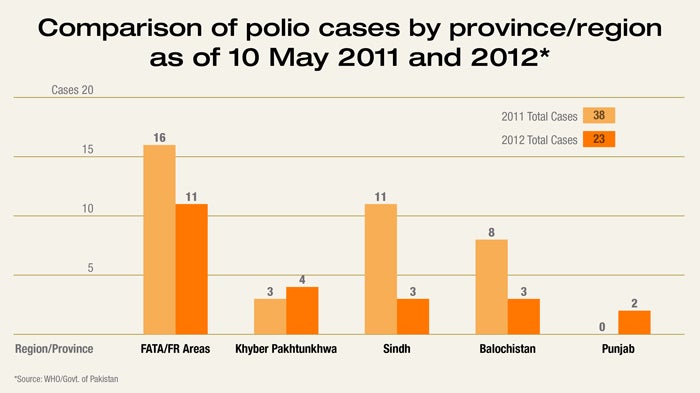

In Pakistan—one of just two countries where wild polio remains endemic—advanced mapping tools have helped vaccination teams reach and protect kids in settlements that weren’t on any official maps. Across sub-Saharan Africa, better geographic data has transformed the fight against malaria by revealing that transmission often clusters in small, hyper-local pockets. Through the Malaria Atlas Project, countries like Nigeria can now track those patterns more precisely—and then get bed nets, testing, and treatment where they’ll have the greatest impact.

With better knowledge of what was killing children, and where, one more fundamental question remained: Why might one child die from a disease while another—who lives in the same place, faces the same risks, and gets the same treatment—survives? This was our third big challenge.

In theory, traditional autopsies would provide the answer. But in the places where most childhood deaths still occur, these invasive procedures are often impossible to perform—too costly, and sometimes opposed for religious, cultural, or personal reasons.

So in 2015, the foundation launched the Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance network, or CHAMPS, which now operates in nine countries across Africa and South Asia. Working with in-country partners, CHAMPS pioneered a new autopsy alternative—using minimally invasive tissue sampling—that can determine causes of death quickly and accurately while respecting local customs and beliefs.

Through CHAMPS, we discovered that childhood deaths rarely have a single cause. Instead, kids often have multiple conditions at the same time, with malnutrition frequently leaving them much more vulnerable to a whole host of infections. (While it rarely shows up on death certificates, it’s an underlying cause of death in nearly half of all child mortality cases.) That finding helped solidify nutrition as a core focus of the foundation’s global health work—and the research, innovation, and product development we invest in. On the ground, we’re supporting partners as they integrate nutrition screening into routine care and train healthcare workers to manage multiple risks at once.

CHAMPS also demonstrated that inadequate prenatal care is responsible for a majority of stillbirths, newborn deaths, and maternal deaths, prompting us to further expand access to maternal health services—like prenatal vitamins and AI-enabled ultrasounds—in the communities where we work.

But the biggest takeaway from CHAMPS is also the most hopeful—and a reminder of why we started the Gates Foundation in the first place: So many childhood deaths could be prevented with existing interventions. We just need to ensure they reach the right children at the right time.

Twenty-five years in, our work on child mortality is far from complete. Still, the impact of what we have learned has been enormous

The Global Burden of Disease, GEMS, and PERCH studies helped shift global priorities by showing the world what was really killing kids—and where new vaccines and treatments could make the biggest difference. Better geospatial tools have empowered countries to pinpoint disease hotspots, find previously unmapped settlements, and distribute life-saving resources where they’re needed most. And CHAMPS is giving governments better data on why children are dying—data that’s now shaping policies, improving reporting, and guiding more effective care.

Most importantly, even as the number of children born every year has gone up, the number of overall childhood deaths has fallen by more than half—from 11.3 million in 1990 to 4.5 million in 2022. Playing a part in making that happen is the best job I’ve ever had, and the most meaningful work I’ve ever done.

At the Gates Foundation, we used to say we could cut child mortality in half again by 2040. The truth, though, is that goal feels further out of reach now—not because the science has stalled, but because support for global health has. The progress we’ve been part of was only possible because governments around the world, including here in the U.S., made long-term commitments to saving lives and followed through. That kind of leadership gave millions of children who would have died a chance at life—and made life better for millions more.

The last 25 years have shown us what’s possible. The next 25 will depend on whether the world keeps showing up for the children who need it most.

PrEP talk

From once a day to twice a year

Long-acting preventatives will save more lives from HIV/AIDS.

I’ve been working in global health for two and a half decades now, and the transformation in how we fight HIV/AIDS is one of the most remarkable achievements I’ve witnessed. (It’s second only to how vaccines have saved millions of children's lives.)

At the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, an HIV diagnosis was often a death sentence. But in the years since, so much has changed. Today, not only do we have anti-retroviral medications that allow people with HIV to live full, healthy lives with undetectable viral loads—meaning they can’t transmit the virus to others. We also have powerful preventative medications known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, that can reduce a person’s risk of contracting the virus by up to 99 percent when taken as prescribed. It’s an incredible feat of science: a pill that virtually prevents HIV contraction.

In theory, if we could get these tools to everyone who needs them and make sure they’re used correctly, we could stop HIV in its tracks. Because when people with the virus receive proper treatment, they can’t transmit it to others. And when people at risk take PrEP, they can’t contract it. In practice, however, getting these tools to people—and making sure they’re used correctly—is the hard part. Especially for PrEP.

That’s because current preventatives require people to take medication every single day. Miss a dose, and protection drops. It’s like trying to remember to lock your front door 365 times a year—if you mess up once, you’re vulnerable. For many people, the barriers stack up quickly. Some have to walk hours to reach a clinic. Others struggle to store medication safely or discreetly at home. And many face judgment and stigma for taking PrEP, especially young women in conservative communities. The very act of protecting yourself can lead to being shamed or ostracized.

That’s why I’m so excited about a new wave of innovations in HIV prevention. Scientists are in the process of developing several longer-lasting PrEP breakthroughs, each with distinct advantages that could help more people protect themselves on their own terms.

Lenacapavir, which requires only two doses per year through injection, could open HIV prevention up to people who can’t make frequent clinic visits. Cabotegravir, another injectable option that works for two months at a time, offers a more flexible dosing schedule than daily PrEP pills, too. Meanwhile, a monthly oral medication called MK-8572, still in the trial stage, could provide an alternative for people who prefer pills to injections. The Gates Foundation is even exploring ways to maintain a person’s protection for six months or longer. And researchers are working on promising PrEP options that include contraception, which would be particularly valuable for women who need both types of protection.

To understand how these options work in real life, and not just in labs, our foundation has supported implementation studies in South Africa, Malawi, and elsewhere. Unlike traditional clinical trials that test safety and efficacy in highly controlled settings, these studies examine how medications fit into people’s lives and work in everyday circumstances—looking at ease of use, cultural acceptance, and other practical challenges. This real-world understanding is crucial for successful adoption.

Some people ask me if these new preventative tools mean the Gates Foundation has given up on finding an HIV vaccine. Not at all. In fact, these advances push us to aim even higher in our research for a vaccine that could prevent HIV for a lifetime—and not just a few months at a time. Our goal is to create multiple layers of protection, much like modern cars have seatbelts, airbags, and even collision-warning sensors. Different tools work better for different people in different ways, and we need every tool we can get.

But even the most brilliant innovations make no difference unless they reach the people who need them most. This is where partnerships become crucial. Through grants to research institutions around the world, the foundation is working to lower manufacturing costs for HIV drugs so they’re accessible to everyone, everywhere. Then there are organizations like the Global Fund and PEPFAR, which have been instrumental in turning scientific advances into real-world impact.

The Global Fund—which needs to raise significant new resources next year to continue its work—currently helps more than 24 million people access HIV prevention and treatment. And PEPFAR has saved 25 million lives since its inception in 2003—a powerful example of how American leadership can build tremendous goodwill while transforming the world. Motivated by the belief that no person should die of HIV/AIDS when lifesaving medications are available, President George W. Bush created PEPFAR with strong bipartisan backing and it continues to serve as a lifeline to millions of people.

We're at a pivotal moment in this fight. Twenty years ago, many believed it would be impossible to deliver HIV treatment at scale in Africa’s poorest regions. Since then, we’ve made fantastic progress. Science has shown us promising paths forward—for better prevention options, easier treatment regimens, and, maybe one day, an effective vaccine. Our task now? Ensuring the life-saving innovations we already have reach the people whose lives they can save.

Game changer

Grassroot Soccer scores a hat trick for African youth

This organization uses the beautiful game to reach millions of young people with lifesaving services.

I’ve never been much of a soccer fan. (Tennis and pickleball are my favorite sports.) Still, seeing the athleticism and passion on display during the World Cup, I understand why soccer has earned the nickname “the beautiful game.” What makes soccer even more beautiful is the positive impact it can have off the field.

There may be no better example of this than the work of a unique non-profit organization called Grassroot Soccer, which was featured at a health innovation event where I spoke earlier this week.

For the last two decades, Grassroot Soccer has used the incredible popularity of the game to help young people across Africa navigate some of their toughest health challenges.

Despite significant progress in health and development in Africa, including a dramatic decline in child mortality, HIV/AIDS continues to be a leading cause of death among youth in Africa. Sexual violence threatens the health and safety of girls. A lack of access to contraceptives contributes to high rates of teen pregnancy. And mental health services are often unavailable.

Solving these challenges is difficult—and especially important given that 60 percent of Africans are under the age of 25. So, how can soccer make a difference?

Because it’s so popular, soccer offers a hook to capture the attention of young people. Grassroot Soccer uses the game to involve them in activities that encourage them to live healthier, more productive lives.

Here’s one simple example. In an activity called “Risk Field,” players are asked to dribble a soccer ball through cones labeled with some of the risky behaviors that young people often encounter, such as unprotected sex, HIV, multiple partners, and alcohol.

The local youth who serve as Grassroot Soccer coaches are a critical component of the program. Trained in basic counseling skills, the coaches play an important role as trusted mentors to the young participants.

The coaches also accompany adolescents to clinics where they can get HIV testing, contraceptives, and other services. (In some countries, young people might be turned away because of their age or criticized by health staff for seeking contraceptives and testing. The coaches serve as advocates to support their right to health services.) Coaches also conduct home visits to talk with parents and guardians about their programs and health services.

Founded in 2002 by Dr. Tommy Clark, a pediatrician and former professional soccer player, Grassroot Soccer initially focused on stopping the spread of HIV. (The Gates Foundation was an early funder of its work.) Today the organization works in more than 60 countries and has reached more than 18 million young people.

Studies have shown that its participants had better access to sexual and reproductive health services, were more likely to stick with their HIV treatment, and were less likely to experience depression.