Ripple effect

As COVID-19 spreads, don’t lose track of malaria

The pandemic is a reminder of why we need to eradicate this mosquito-borne disease.

Mosquitoes don’t practice social distancing. They don’t wear masks, either.

As COVID-19 spreads across the globe, it’s important to remember that the world’s deadliest animal hasn’t taken a break during this pandemic.

Mosquitoes are out biting every night, infecting millions of people with malaria—a disease that kills a child every other minute of every day.

Most of these deaths occur in the poorest countries with the weakest health systems. Now, they face the added burden of halting the coronavirus. And in many of these countries, COVID-19 cases are likely to peak at the worst possible time: the height of their malaria transmission seasons.

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, endemic diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS contributed to many more deaths than Ebola because the epidemic disrupted local health care systems. Health officials fear the same could happen with COVID-19.

Lockdowns and social distancing regulations have already made it difficult for health workers to provide malaria prevention and treatment in many parts of Africa. There have also been interruptions to supplies of essential malaria tools—like bed nets, anti-malaria medicines, and rapid diagnostic tests—that have been instrumental in cutting malaria deaths by more than half since 2000.

Now that incredible progress may be in jeopardy. A recent modeling analysis from the World Health Organization found that if essential malaria prevention and treatment services are severely disrupted by the pandemic, malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa would reach mortality levels not seen since 2000. That year, an estimated 764,000 people died from malaria in Africa, most of them children.

There is not a choice between saving lives from COVID-19 versus saving lives from malaria. The world must enable these countries to do both. Health officials urgently need to step up to the challenge of controlling the pandemic while also making sure that malaria, as well as other diseases like HIV and tuberculosis, are not neglected.

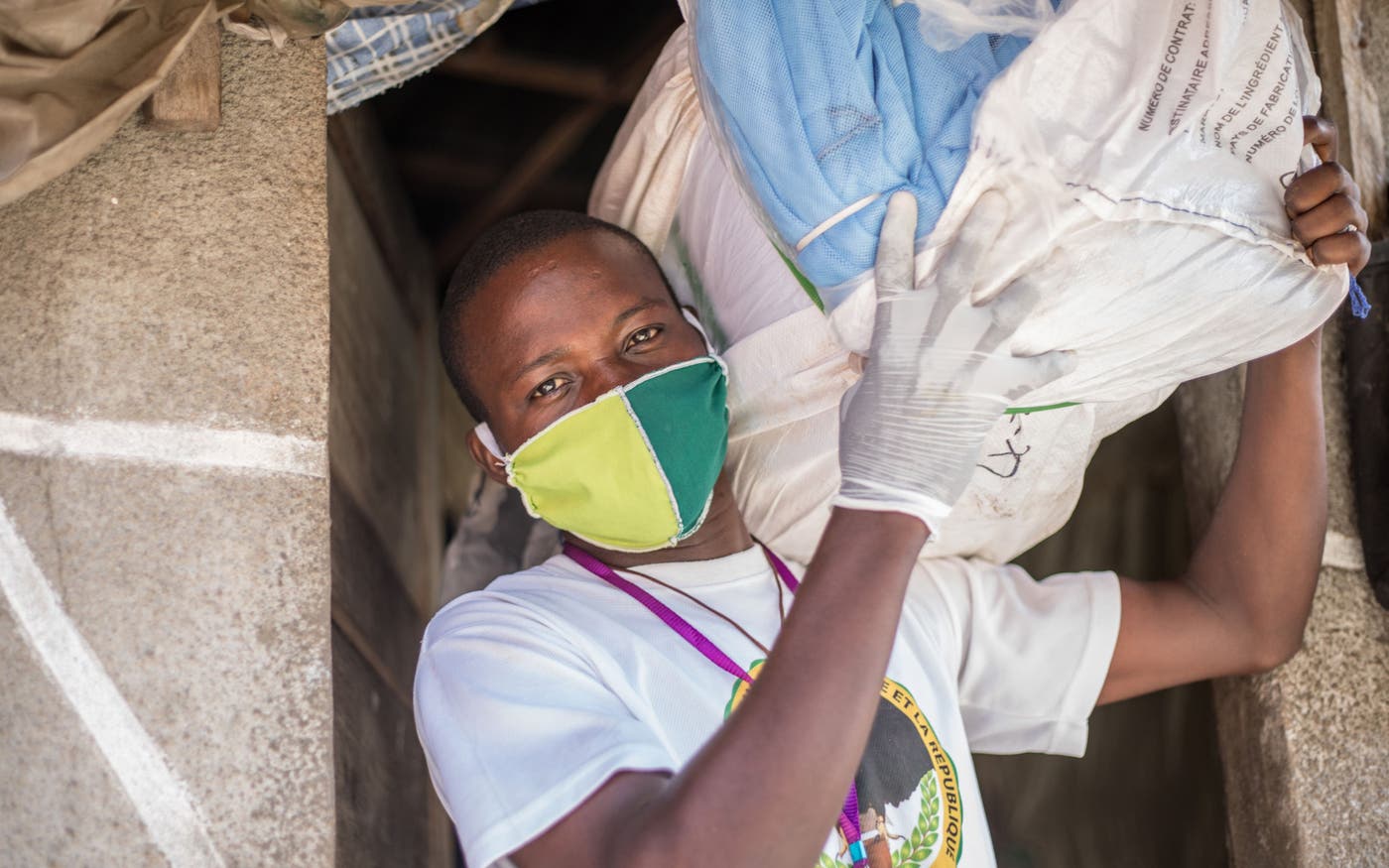

For malaria, that means continuing with campaigns to deliver long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets, control mosquito populations with indoor spraying, and provide preventive treatment for pregnant women and children in high-risk communities. At the same time, health workers must deliver these services while not putting their communities at risk of the coronavirus.

The good news is that many countries are finding ways to maintain key malaria programs even in the face of the pandemic. In Benin, a country in West Africa with one of the highest burdens of malaria in the world, the government teamed up with Catholic Relief Services and our foundation this year to develop a new, innovative way to distribute bed nets across the country. Using smartphones, real time data collection, and satellite mapping, Benin has helped ensure that all families, no matter where they live, will be protected by a bed net at night. And scientists haven’t paused research efforts to find new ways to prevent malaria and control mosquito populations, like those underway at “Mosquito City” in Tanzania.

What’s exciting to see is how some existing malaria programs are also helping to control COVID-19. For example, emergency operations centers that track outbreaks of malaria in Africa are now being used to monitor the spread of COVID-19. By tracking the shape and movement of the pandemic across countries and regions, health officials are also able to deepen their understanding of health conditions in communities that will, in turn, help improve their responses to malaria in those areas.

The progress the world has made against malaria is one of the greatest global health success stories. The COVID-19 pandemic only reinforces why eradicating malaria is so essential. So long as malaria exists, it will continue to flare up and burden the most vulnerable communities. Ridding the world of preventable, treatable diseases like malaria will save millions of lives and lead to healthier, more prosperous communities. And that will make them better prepared to confront any new health challenges like COVID-19 in the future.