COVID coverage

Next time, we can close the vaccine gap much faster

How to use vaccines more fairly and effectively.

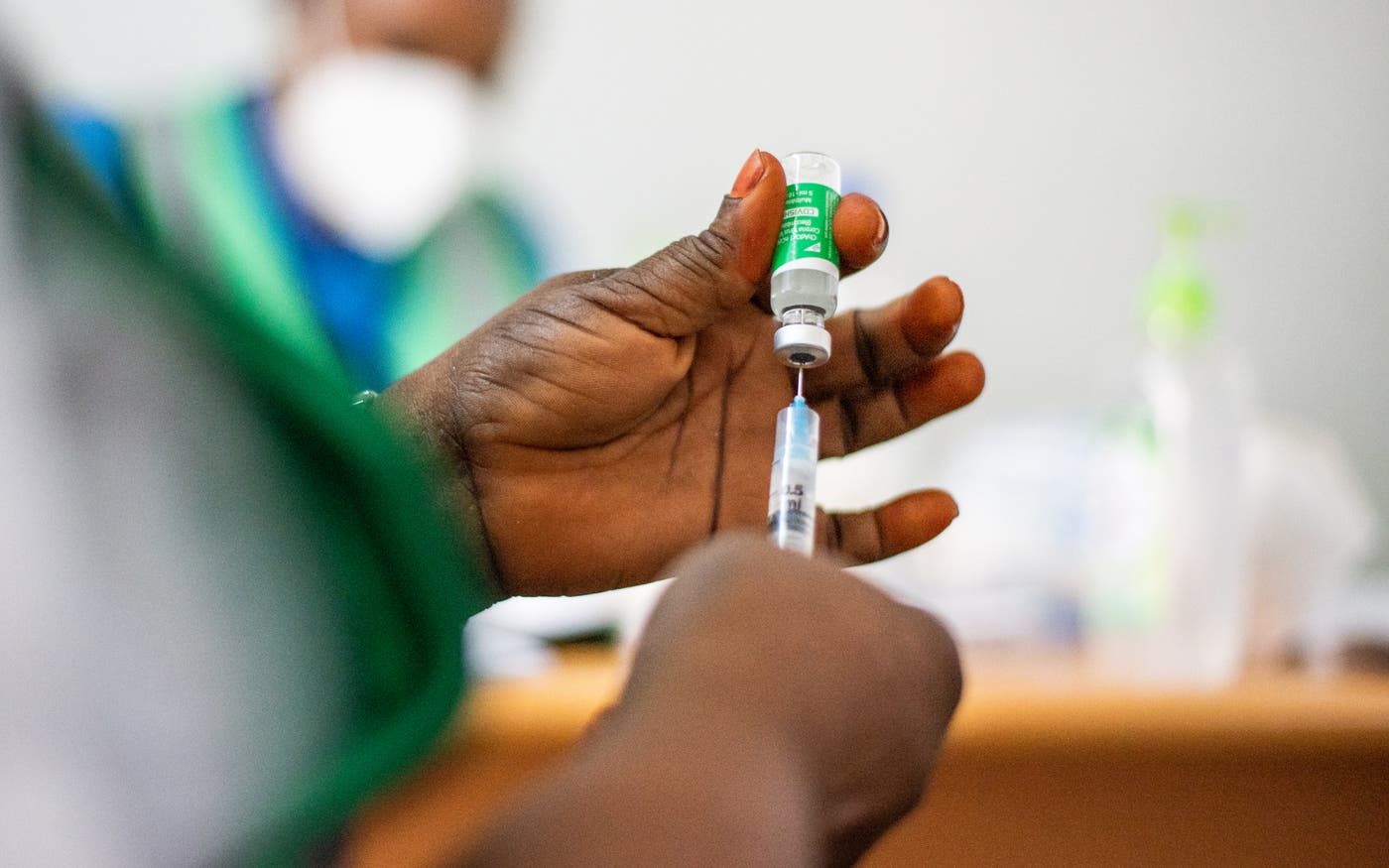

Today, 46 percent of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. It’s hard to overstate what a remarkable achievement this is. Humanity has never made and distributed a vaccine for a disease faster than it did for COVID-19. It accomplished in 18 months something that used to take a decade or more.

But within this amazing success there is a startling disparity: Just over 2 percent of people in low-income countries have received any COVID-19 vaccines. And the gap will be harder to close as rich-world governments buy up extra doses to serve as booster shots.

People are right to be upset about the inequity here. Vaccines make COVID-19 a largely preventable disease—and a survivable one in all but the rarest cases—and it is heartbreaking to know that people are dying of a disease not because it can’t be stopped but because they live in a low-income country.

Sadly, this inequity is not new. It is not even the worst gap in global health. There were shocking disparities in health long before any of us had heard of COVID-19.

Every year, more than 5 million children die before their fifth birthday, mostly from infectious diseases, and almost entirely in low- and middle-income countries. A child in northern Nigeria is 20 times more likely to die before the age of 5 than a child in a rich country. That is simply unjust, and reducing this inequity has been the Gates Foundation’s top priority for more than 20 years.

If you step back and look at the trends, though, there is good news. Since 1960 the childhood death rate has been cut by more than 80 percent, thanks in large part to the invention and distribution of vaccines for children around the world.

The fact that routine childhood vaccines are reaching so many people is reason to believe COVID-19 vaccines can too. Providing them to everyone who needs them is one of three crucial steps in controlling this pandemic, along with containing the virus so it doesn’t come roaring back and coordinating the global response. At the same time, we can learn from the inequities that were so clear during this pandemic so we can do a better job of closing the gap during the next one. (Assuming there is a next pandemic. I think it is possible to prevent them altogether. But that’s a subject for another time.)

How could we achieve vaccine equity in a future pandemic? I see two ways.

1. Change how the world allocates doses.

What would the optimal allocation look like? It’s not simply a matter of proportional representation, where if your county has X percent of the world’s population, you get X percent of the vaccines. There are two different benefits to consider, and both are important.

One benefit is to the individual who’s immunized; they get protection from the virus. The more likely you are to get infected—and the more likely you are to become seriously ill or die if you do get infected—the more benefit you get from a vaccine. A COVID-19 patient in their seventies is 90 times more likely to die of the disease than a patient in their twenties. From a global perspective, it is neither fair nor wise to protect that young person before the old one.

Second, when an individual is vaccinated, society gets the benefit of lowering the risk that the person will spread the disease to others. This is the core of the argument in favor of vaccinating health workers and people who work in elderly care facilities, since even when a lockdown is in place, they can transmit the virus to people at high risk.

When a virus is spreading, we should maximize both benefits—saving lives and stopping transmission. This means that, when supplies are short, we should prioritize vaccinating people who both have a high risk of death and live in the places where the virus is spreading fastest.

Those will not necessarily be low-income countries. When COVID-19 vaccines first became available, many of the most severe epidemics were in rich- and middle-income countries.

The gravest inequity, even more than vaccinating rich people before poor ones, is vaccinating young people in rich countries before older people in middle-income countries with bad epidemics, such as South Africa and most of South America.

To their credit, rich countries have pledged to share more than a billion doses with poorer countries during COVID-19. But they haven’t yet delivered fully on those pledges, and even if they had, the gap would still be enormous.

Although sharing doses needs to be part of the solution, it will never be sufficient to solve the problem. For one thing, the number of doses won’t be high enough. And will future politicians always be willing to tell young voters they can’t be vaccinated because the doses are going to another country, at a time when schools are still closed and people—including a few young people—are still dying?

That’s why it’s so important to find ways to produce more doses in less time. The world should have the goal of being able to make and deliver enough vaccines for everyone on the planet within six months of detecting a potential pandemic. If we could do that, then the supply of doses would not be a limiting factor, and the way they were allocated would no longer be a matter of life and death.

2. Make more doses.

As limited as the supply of COVID-19 vaccines has been, the situation could have been even worse.

We are fortunate that mRNA vaccines work so well, since this is the first disease for which the mRNA technology has been used. If they hadn’t, we would have been far worse off.

It is also great that some vaccine companies entered into second-source deals, which allowed huge volumes of their vaccines to be manufactured by other firms. This was a crucial and remarkable step. (It’s as if Ford let Honda use its factories to build Accords.) Just one example: In less than two years, a single manufacturer, AstraZeneca, signed second source deals involving 25 factories in 15 countries.

You may have heard the argument that waiving intellectual property (or IP) restrictions would have made a difference. Unfortunately, that’s not true in this case. IP waivers and licensing are a complicated issue, so I want to take some time to untangle it.

There are cases in which IP licensing is a great way to make something cheaper and better. For example, in 2017, the Gates Foundation and a number of partners were involved in an agreement to make a new, more effective version of an HIV drug cocktail that would be more affordable for the world’s poorest countries.

In the deal, a pharmaceutical company gave the recipe for the key ingredient in this cocktail to firms that specialize in producing generic drugs. These firms were able to reduce the cost so much that today nearly 80 percent of people who get HIV treatment in low- or middle-income countries are receiving the improved cocktail.

Unfortunately, IP licensing doesn’t work as well with vaccines. Here’s why.

Many drugs are made using chemical processes that are well defined and measurable. If you mix the same ingredients in the right proportion and so on, you’ll get the same product every time, and you can check your work by looking at the chemical structure after the drug is made. Company A can give a recipe to company B, and company B will be able to make precisely the same drug consistently.

But many vaccines don’t work that way. Manufacturing them often involves living organisms—anything from bacteria to chicken eggs. Living things don’t necessarily act exactly the same way every time, which means that even if you follow the same process twice, you might not get the same product both times. Even an experienced vaccine maker might not be able to simply take another’s recipe and replicate it reliably.

This is why broadly waiving IP protections would not meaningfully increase the supply of vaccines. (In the case of COVID-19, though, a narrow waiver that applied to specific easily transferred technologies during the pandemic made sense.) Supply has been limited not because of IP rules, but because there aren’t enough factories capable of handling the more complicated process of making vaccines.

Licensing IP—or having the rights to it waived—only guarantees that company A can’t sue company B. Second-source deals are far superior because they involve sharing not only the recipe but also knowledge about how to use it, as well as personnel, data, and biological samples. It was a second-source deal with AstraZeneca—not an IP waiver—that allowed Serum Institute of India to produce 100 million doses at a very low cost and in record time.

So how can the world make more doses faster next time?

First, decision makers should get serious about expanding the world’s vaccine-making capacity. In particular, governments and industry should make sure there’s enough capacity to quickly make huge volumes of mRNA vaccines; now that we know the mRNA platform works, it will allow new vaccines to be developed faster than any other approach. And if companies that have second-source deals now maintain their relationships with each other, they won’t have to start from square one in the next outbreak.

Another step is to develop prototype vaccines against the diseases that are most likely to cause future outbreaks, and to develop universal vaccines for flu and coronaviruses, which would protect people against any form of the two pathogens. The NIH and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations are doing excellent work on both, but even more research is needed.

One longer-term step is for more countries to build the capacity to develop, manufacture, and approve vaccines themselves.

Historically, the companies that invent new vaccines have been based in higher-income countries. Because it costs so much to develop a new product, they try to recoup their costs as quickly as possible by selling doses at the higher prices that rich countries can afford. They have no financial incentive to try to lower their costs (by optimizing the production process, for example) so that the price can be cheap enough for lower-income countries.

The pentavalent vaccine—which protects against five diseases—is a great example. It was invented in the early 2000s, but there was only one manufacturer, and at more than $3.50 per dose, it was far too expensive for low- or middle-income countries. Our foundation and other partners worked with two vaccine companies in India—Biological E Limited and Serum Institute of India—to develop a pentavalent vaccine that would be affordable everywhere. Today that vaccine costs about $1, and it is given to 80 million children a year. That’s a 16-fold increase since 2005.

We need more examples like this. Pentavalent took years to pull off. If there were more high-volume vaccine manufacturers whose primary goal was to produce low-cost vaccines, then affordable doses would be available much faster. Middle-income countries are a natural home for these companies, and some have set ambitious goals for themselves. For example, a group of African leaders has set a target of manufacturing 60 percent of the continent’s vaccines by 2040.

Helping middle-income countries build their vaccine-making capacity is something the Gates Foundation has been working on for two decades. We’ve helped bring 17 vaccines to market, and we’re supporting the African efforts to build theirs out by 2040.

What we’ve learned is that creating an entire vaccine-making ecosystem is a tough challenge. But the obstacles can be overcome.

One issue is the need for regulatory approvals. Vaccine factories are required to be approved by what’s known as a “gold-standard” regulator. India is the only developing country with a gold-standard regulator; factories in any other developing country have to be approved by their own government first, and then by the WHO. It’s time-consuming.

Regional agencies in Africa are working with the WHO and the European Union to create gold-standard regulation on the continent. Governments are also collaborating on regional standards for vaccines, so manufacturers don’t have to meet different safety and efficacy requirements in each country.

Another challenge: If vaccine manufacturers don’t have other products to make between outbreaks, they’ll go out of business. Unfortunately, making existing vaccines isn’t a viable option, at least right now, because the market is already saturated with existing vaccines, and it would be hard for new entrants to compete on price with established low-cost / high-volume companies.

But new products are coming that would be ideal products for them. As vaccines become available for diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV, they’ll create opportunities for producers in middle-income countries. In the meantime, countries can take on the fill and finish process—putting vaccines made elsewhere into vials and distributing them.

To anyone who has lost a loved one to COVID-19, or had to choose between paying the rent or buying food, it is no comfort to suggest that anything has gone well in this pandemic. But as my friend the late Hans Rosling used to say, “The world can be both bad and better.” The situation today is bad, and also better than it would have been if COVID-19 had come along ten years ago. If the world makes the right investments and decisions now, we can make things better next time. And maybe even make sure there is no next time at all.

This post originally appeared on CNN.com.