Fighting to End a Disease

How the U.S. battled polio

The polio epidemics of the past were terrible and unsettling times.

Talk to anyone old enough to remember polio epidemics in the U.S., and you will see the fear in their eyes as they talk about those terrible and unsettling times. For decades, no one knew why thousands of children would suddenly be stricken—usually in midsummer—with many dying or left permanently paralyzed.

Today, most of us in the U.S. don’t even think about polio. But if you go to villages in India’s Bihar Province or the northern states of Nigeria, or the southern part of Afghanistan, you will see that very same fear in the eyes of parents who worry that their child might be next.

I’m a dogged advocate for polio eradication and have written about it in many other articles on the Gates Notes. We are very close to ridding the world of this terrible disease once and for all. It will take focus and commitment to get it done, but I am confident we can.

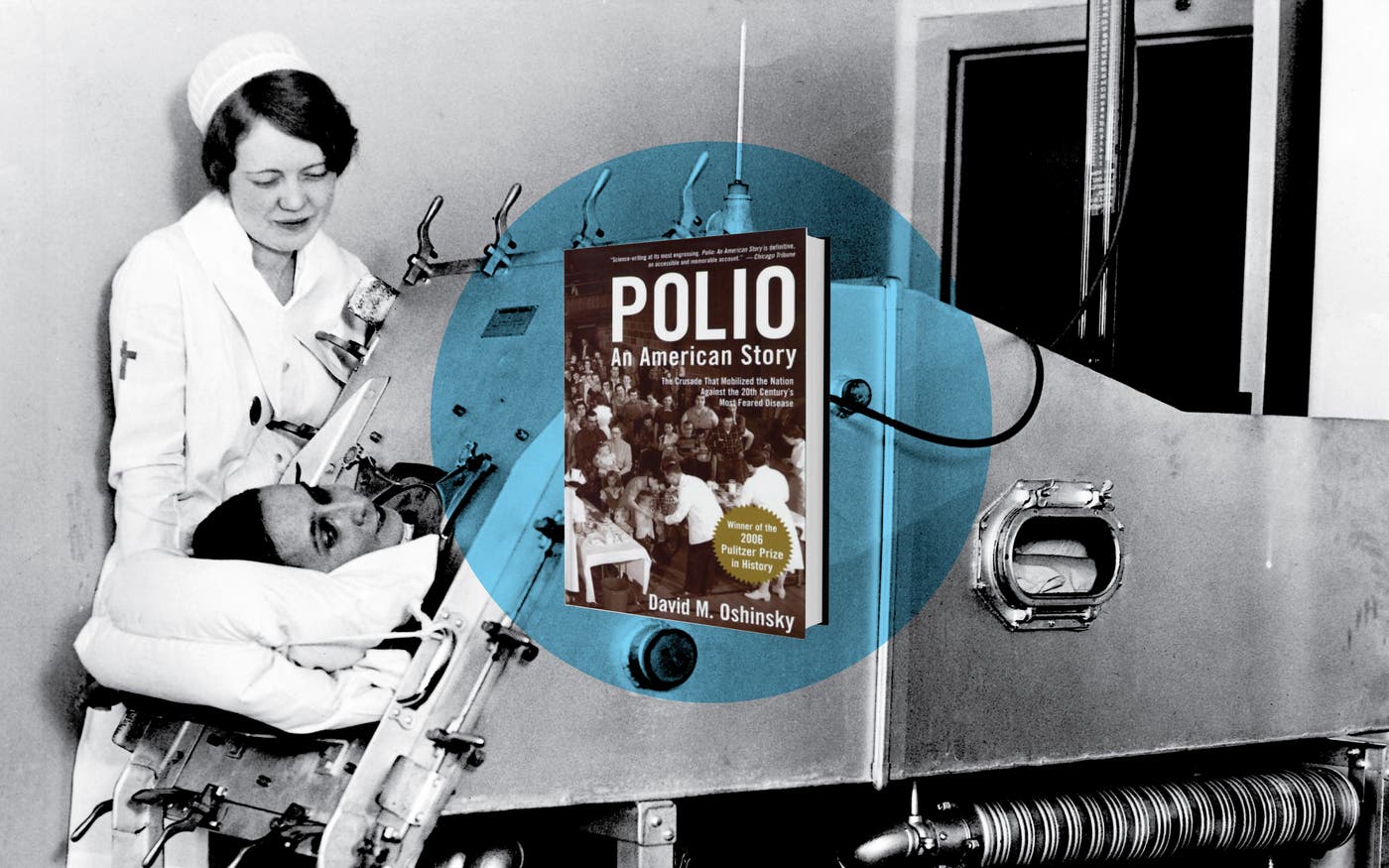

That’s why I’m a fan of David Oshinsky’s insightful book, Polio: An American Story. (I’m not alone here, as it received the Pulitzer Prize for history in 2006.) It is a fascinating account of the search for a vaccine to stop the polio epidemics that swept the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century, and the remarkable efforts that led to its successful eradication from the U.S. and most other countries. Reading Oshinsky’s book a few years ago broadened my appreciation of the challenges associated with global health issues and influenced the decision that Melinda and I made to make polio eradication the top priority of the foundation, as well as my own personal priority.

Oshinsky retraces the steps of researchers trying to puzzle together how to create an effective vaccine. He’s a gifted storyteller who makes complex scientific subjects easy to understand and also captures the mood of a country terrorized by an invisible and little-understood disease. He describes in meticulous but never-boring detail the people and politics associated with one of the most important medical breakthroughs in history.

I found it interesting that the first recorded polio epidemic in the U.S. didn’t occur until 1894, in rural Vermont. By 1908, Karl Landsteiner, a Viennese researcher who later won a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the different human blood types, isolated the poliovirus by injecting monkeys with an emulsion from the spinal cord of a boy who had just died of polio. It was one of several important breakthroughs in the early 20th century battle against killer infectious diseases, including malaria, tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhoid, and syphilis.

In 1916, a polio outbreak in New York City quickly spread to adjacent states. Despite intensive sanitation measures of the kind that had helped control other epidemic diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever, 27,000 people died that summer. In New York City, 80 percent of those who died were under five.

I knew that Franklin Delano Roosevelt contracted polio, but did not realize until reading Oshinsky’s book how significant an influence FDR had on the search for a vaccine. He was struck in the fall of 1921 while on a family vacation in Canada. The news stunned Americans, who at the time believed the disease mainly occurred among poor children in slums. FDR was 39 and from a wealthy New York family.

For thousands of polio victims, Roosevelt symbolized that life could go on for those disabled by the disease. He helped found the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now known as the March of Dimes, which provided aid to victims and funded polio research. I was impressed that even as president, FDR would often respond personally to letters sent to him by other victims. Yet, Roosevelt also went to great lengths—abetted by a cooperative press corps—to hide the fact that he needed leg braces and handrails to stand, and a wheel chair to get around. I can’t imagine an American president being able to do that today, but FDR was greatly admired at a time when the nation was dealing with a world war and the Great Depression. Somehow, he persuaded the media that obscuring the extent of his disability was necessary to reassure the public that he was healthy and capable of holding public office.

I was also fascinated by the media savvy and marketing sophistication of the March of Dimes, which used famous Hollywood actors to get out its message and was the first philanthropic organization to introduce the idea that millions of Americans—not just the wealthy—could play an important role in helping solve big social problems. In 1938, Americans mailed nearly 2.7 million dimes directly to the White House in support of that year’s March of Dimes campaign.

We sometimes take for granted the speed of scientific breakthroughs today. Yet, Oshinky’s book reminded me of the painstaking efforts scientists often must undertake. Forty years after the polio virus was discovered, scientists still didn’t know what caused it. Theories ranged from rotten fruit to houseflies to contaminated milk. They didn’t know the mechanism by which it attacked the central nervous system. They didn’t know if there was just one type of polio, or many. And they didn’t know how to grow poliovirus safely, and in large enough quantities, to produce vaccines.

Also, researchers were divided over whether a “live-virus” vaccine or a “killed-virus” vaccine would be more effective. Most virologists believed a live-virus vaccine would stimulate higher antibody levels in the blood and create a lasting immunity. Advocates of the killed-virus vaccine believed it could be just as effective, and would eliminate any risk that someone receiving an immunization could contract polio.

Jonas Salk, a young researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, was one of those who believed a killed-virus vaccine would work. It had, after all, been effective against cholera, typhoid, and diphtheria. From 1949 to 1951, Salk and his team conducted extensive testing on thousands of monkeys, using samples from human polio victims and from monkeys who had contracted the virus after being injected with the human samples. Salk’s work confirmed what had been suspected but not yet proven—all of the identified and tested strains of poliovirus fit into one of three distinct types.

About the same time, John Enders, a researcher at Harvard, figured out how to grow poliovirus that would be safe and could be mass produced. But scientists were still stymied over how the virus was transmitted and traveled through the body. Several prominent researchers had long believed that it entered through the nose and traveled directly to the central nervous system, bypassing the bloodstream. If that was the case, a vaccine that stimulated antibodies in the bloodstream would have done no good.

Two scientists working independently, Dorothy Horstmann at Yale and David Bodian at Johns Hopkins, upended the prevailing thinking with a breakthrough discovery. Previous researchers had been unable to detect poliovirus in the blood because they were not looking for it soon enough. Horstmann and Bodian discovered that the poliovirus is in the bloodstream for only a brief period of incubation before the body’s immune system creates antibodies that destroy it.

Salk was relentless in his pursuit of a vaccine. He began human trials against the backdrop of the worst outbreak of polio on record in the U.S.—57,000 cases in 1952. By the spring of 1954, more than 1.3 million children had taken part in the largest vaccine trial in history. It took a year for the results to be reported, and when they were, church bells tolled, factory whistles rung, and then-President Dwight Eisenhower—a war hero—broke down in tears.

Although not 100 percent effective, the Salk vaccine was considered a huge success and a great relief for an edgy nation. In 1956, the number of polio cases in the U.S. dropped by 50 percent compared to the year before, and by another 50 percent the following year.

Meanwhile, Sabin was about to undertake the largest medical experiment in world history—a live-virus vaccine administered to 10 million children in Russia. It, too, proved a success. Considered more effective and easier to administer than the Salk vaccine, Sabin’s oral vaccine won out by 1963.

Oshinsky’s narrative ends at about this point, but the quest to completely eradicate polio is still ongoing. In 1987, the World Health Organization launched a global initiative to eradicate polio worldwide. Since that time, about 2.5 billion children have been vaccinated, and the number of polio cases has decreased by 99 percent. Last year there were fewer than 1,500 cases in just four countries—India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

While this is fantastic progress, the last remaining cases pose a serious danger. If not completely eliminated, polio will spread back into countries where it has previously been eradicated, killing and paralyzing perhaps hundreds of thousands of children.

The foundation is deeply involved in this final push, and I am personally committed to doing what I can to rid the world of this dreaded disease once and for all.