Go fund Global Fund

The world is uniting to help this group

They’ll be saving 14,600 lives every day.

I was in Lyon, France, yesterday with leaders from around the world to celebrate an achievement that, strictly speaking, hasn’t happened yet.

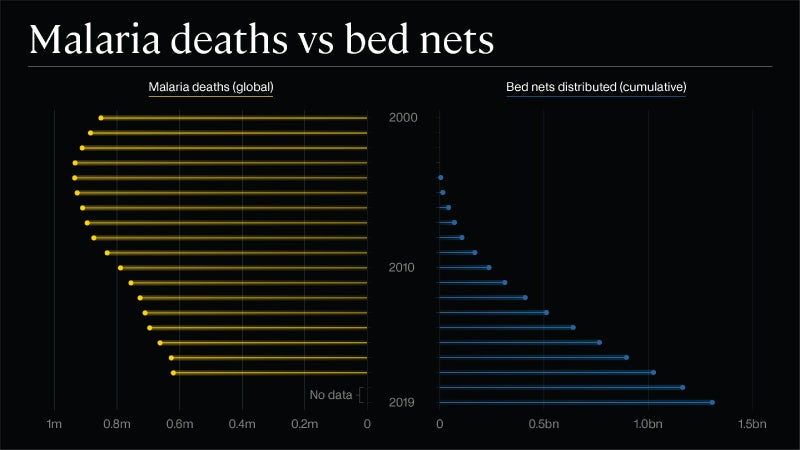

We were all in Lyon to pledge new funding for an organization that has changed the world. It’s called the Global Fund, and since it was created in 2002, the fund has helped drive phenomenal progress on AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria in the world’s poorest countries. For example, since 2004, the Global Fund has distributed 1.3 billion bed nets to help stop malaria—one of the major reasons that malaria deaths have dropped by about 40 percent since 2000.

When I spoke yesterday, we didn’t know exactly how much money was going to be pledged. Now we do: It’s more than $14 billion, the largest sum ever raised by the Global Fund. (Our foundation committed $700 million over the next three years.) When all the funding kicks in—and as we get more innovations like new bed nets and HIV drugs—we’ll be able to report a remarkable accomplishment: The Global Fund will save 14,600 lives every day for the next three years.

Here’s the speech I gave at the conference yesterday:

Thanks very much, everyone. I want to especially thank the people of France for hosting this year’s replenishment – and President Macron for all he’s done to make sure it’s a big and successful one.

The other thing I want to say is: I’m really inspired by the generosity of the people in this room. We don’t know the exact total of the pledge yet, but from what I’ve heard this morning, it sounds like the world will commit more to the Global Fund than ever before.

That’s a huge accomplishment, especially when you consider the political moment we’re living in. More and more, countries seem to be stepping back from the world and saying they’ll cut things like foreign aid. If there’s a narrative about how the globe is turning, it is that it’s turning inward.

But that’s not what’s happening here. Many of the nations represented here have become MORE engaged – and have increased funding for the Global Fund by upwards of 15% since the last replenishment.

And the pledge amount is getting slightly bigger right now: Our foundation is very proud to commit $700 million to the Global Fund over the next 3 years.

But I don’t want to spend too much time today talking about fundraising totals. Because I actually think that undersells what this room has achieved.

What does the dollar amount tell us about what the Global Fund will do – and has done already? Not very much.

To see why giving this money to this institution is so important you have to dig beneath the fundraising totals.

So that’s what I want to do today. I want to show how you how your support of the Global Fund has changed the world – and how it will continue to change it.

I think the best way to begin is with the story of bed nets. They’re a really old invention. The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus wrote about how Egyptians living on the banks of the Nile River would fish with their nets during the day – and then sleep under them at night to keep away malaria-transmitting mosquitos.

This was the 5th century BC – and for thousands of years, that’s basically how malaria prevention remained in many parts of the world: a basic barrier between humans and insects.

It’s only been within the last generation or so that a new approach was developed for fighting malaria with bed nets. The concept was to coat the nets with insecticide – and then hand them out by the millions, and for free, in endemic countries.

And this is where the Global Fund came in.

In 2002, the Global Fund was founded, and by 2007 – just 5 years later – it had helped distribute more than 50 million nets. Then look what happened: Malaria deaths, which had been increasing globally, finally started to decline. And they kept declining.

In the years since, the Fund has delivered 1.3 billion bed nets. (131 million were delivered last year alone). And as all this happened, you can see that malaria deaths dropped by about 40 percent from their peak.

This is the first really important thing I think people need to understand about the Global Fund. Big multilateral institutions often have a reputation of being slow and ineffective. But the Global Fund is one of the fastest-scaling, most effective institutions the world has ever created.

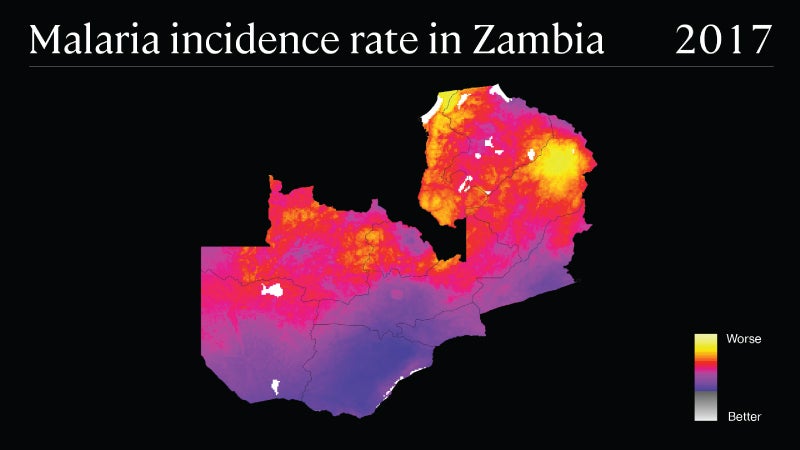

In fact, the numbers are more impressive when you dig in to country- and regional-level data. For instance: Today, a young girl in Zambia is half as likely to die of malaria than her mother was at her age.

Or how about this? Back in the year 2000, a girl in the Manipur region of India had about a 1-in-1,500 chance of contracting malaria. But today the odds are less than 1-in-30,000.

And it’s not just malaria. Look at HIV.

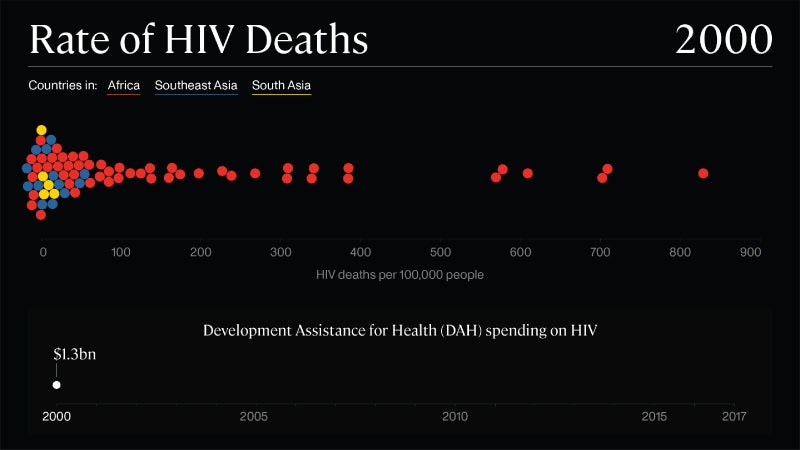

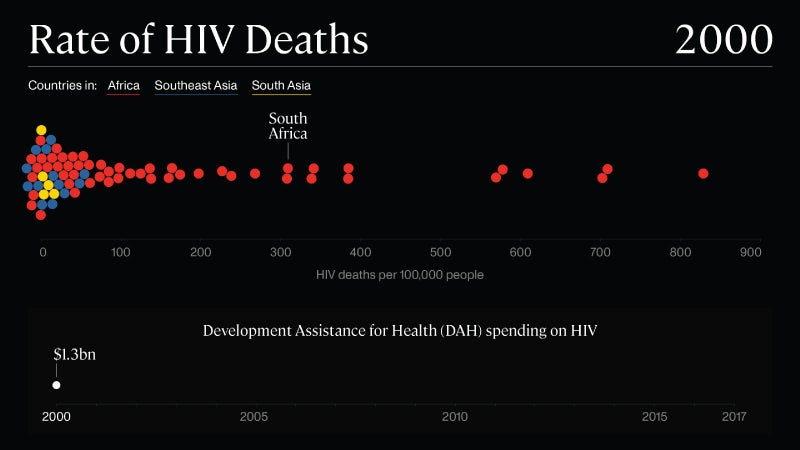

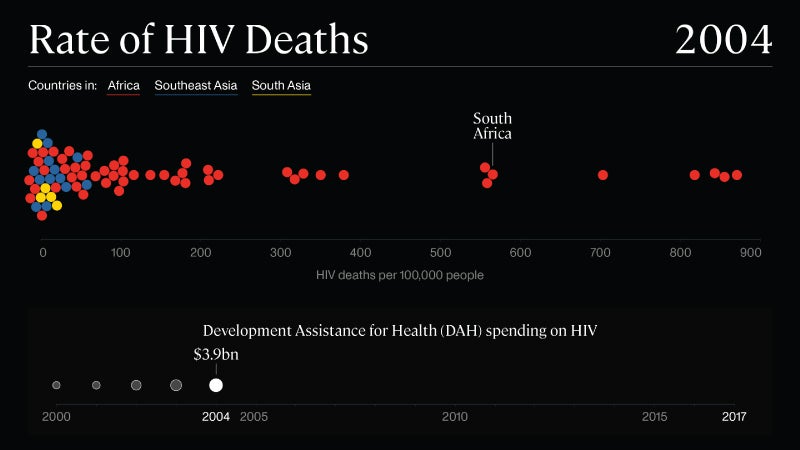

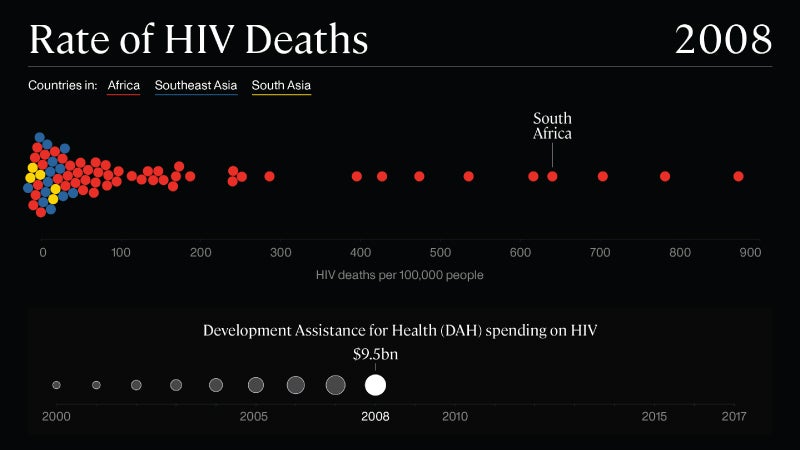

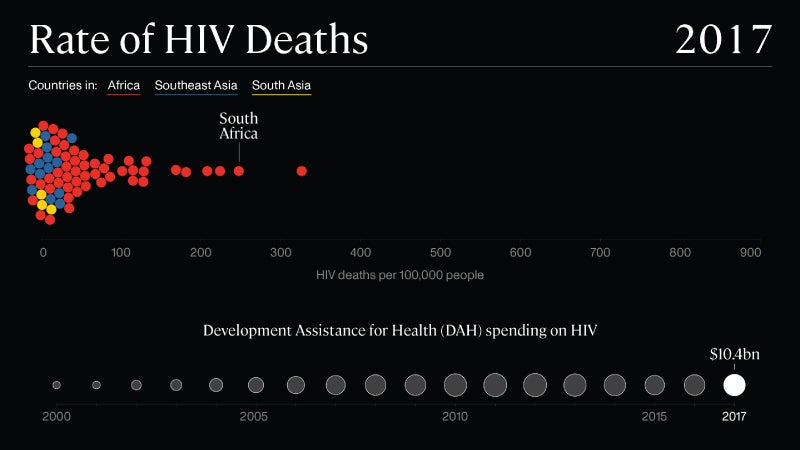

These dots represent different countries in Africa and Asia in the year 2000. The farther right the dot is on the graph, the higher the odds someone in that country would die of AIDS-related causes.

Focus on South Africa for a moment. If you were living in South Africa in the year 2000, you had a 1-in-300 chance of dying of AIDS just that year.

Those odds ticked up over the next few years: By 2004, they increased by 50%.

By 2008, they doubled.

But then, look what happened around 2008, just six years after the Fund launched: The odds start to drop – and then plummet.

As the Global Fund scaled up, you can literally see the tide turn in the fight against disease.

And these dots will continue to move farther and farther left. Because the Global Fund is constantly getting better at what it does; it’s constantly learning.

Let’s go back to malaria. The year the Global Fund launched was when the first Anopheles mosquito genome sequence was published. We didn’t even have a very good estimate of how many people were dying of the disease worldwide.

But now, we sequence thousands of malaria mosquito genomes every year. And in some countries, we know exactly how many cases of malaria there are down to the village-level.

Here’s an example. This is a malaria-heat map of Zambia.

You can see, in granularity, where the incidence of the disease is highest, and that helps us fight the disease in a much more targeted way, sending the right types of nets to the right places. Because the bed nets themselves have also become more advanced, too.

It used to be that every insecticide-treated bed net made had one ingredient: a pyrethroid insecticide compound. Over the years, though, mosquitos became widely resistant to the chemical. So much so that when we sequenced mosquito genomes, we found that the same resistance gene had evolved independently in many different parts of Africa.

Fortunately, there’s a new generation of bed nets – the Interceptor G2. I have one right here.

You can’t tell by looking at it, but this net is cutting-edge science. It pairs pyrethroid with a different compound, one that’s harder for the mosquitos to evolve against.

In fact, our foundation is working with BASF and MedAccess – and the Global Fund – to make sure 35 million of these nets are manufactured and delivered over the next three years.

This brings me to my next point, and another one that I think is overlooked when we talk about the Global Fund: It is the world’s main artery between research labs – and the people who need the drugs and other medical supplies that they invent. When there’s a breakthrough in the science, the Fund makes sure that breakthrough helps as many people as fast as possible.

Over the past three years, for example, the Fund has helped deploy new anti-retrovirals to treat HIV.

The main challenge with anti-retrovirals is that people have to take them their entire lives – which means it’s easy for the disease to become resistant. That was the case with the old essential HIV drugs, what’s called the first-line regimen.

But back 2017, the WHO recommended new drug called dolutegravir. Not only is it cheaper, it’s harder for the virus to become resistant to dolutegravir.

Now, thanks to the Global Fund, there’s enough dolutegravir supply for more than 7 million people. And the Fund has made sure it’s getting to them super-fast.

When the previous first-line regimen needed to be upgraded, it took 3 years to start swapping out the old drug for the new one. In this case, we’ve cut the time in half. It’s only taken 18 months.

And that’s just a current example. Over the next three-to-five years, the innovations flowing out of the pipeline will be more impressive. That includes the bed net I showed you – but it also includes new TB drugs.

Many strains of tuberculosis have grown resistant to current drugs, but there’s a new triple drug regimen, that is showing a lot of promise even against the most resistant forms of the disease. This regimen has fewer side effects than the old TB drugs – and works up to three times faster: It can get rid of the disease within 6 months.

There’s also a new TB vaccine in clinical trials. If it’s successful, it would be the first new TB vaccine in a century – and would supersede the current one, which is only modestly effective and only works in infants.

What I’m most excited about, though, are the breakthroughs in treating and preventing HIV…

Right now, someone needs to take a cocktail of drugs every day in order to adequately prevent an HIV infection. But following that schedule can be extremely difficult, especially for some young women in sub-Saharan Africa who can’t keep HIV drugs at home because of certain stigmas.

A recent study prescribed the drugs to a group of 427 women living in South Africa and Zimbabwe. After a year, it found that less than 8% of the women had enough of the drug in their bloodstream to prevent against the disease.

Going from a daily dose – to, let’s say, a monthly dose – could dramatically boost those numbers. Because it’s much easier to take one pill a month – rather than 30. And women might not even have to keep it at home. They could go to a local clinic.

This is exactly what we think is going to happen: Within the next few years, a new HIV drug is going come on the market for treatment and shortly afterwards for prevention. One dose a month would be enough to prevent the disease entirely.

And this is just the beginning. A matchstick-size implant is in the works. It would be inserted just under the skin of someone’s upper arm, and that would be enough to prevent HIV infection for an entire year.

We think this innovation is a few years farther out, but when it’s ready, we can be confident that the Global Fund will have it saving lives as fast as possible…

Positive stories like these are really important for us to keep telling… because they aren’t told very often. Most people only hear the bad news about disease.

In fact, that’s how Melinda and I first got into philanthropy. Two decades ago, we read an article about how children were dying from a preventable disease by the hundreds of thousands. And there were a lot of those articles to choose from.

The millennium’s first issue of Newsweek featured a cover that read “10 Million Orphans” and said that in sub-Saharan Africa, “AIDS has been cutting through the population like a malevolent scythe.”

Later that year, the German publication, Der Spiegel, ran a story saying that “Africa [was] just the beginning.” The article was titled “Time Bomb on the Doorstep” and predicted that the AIDS crisis would lead to the collapse of entire nations – not only in Africa, but around the world.

Of course, none of those predictions ever came true. The world started getting healthier, not sicker. And yet, people’s perceptions haven’t caught up to this new, better reality.

Before he passed away two years ago, my friend Hans Rosling used to test people’s basic knowledge about global health. And he found that people consistently thought the world was worse off than it actually was.

This is understandable. It’s the nature of news that we rarely hear the good kind. We’re told when people get sick – not when they stay healthy.

Still, it’s a tragedy that we don’t hear the good news. Because good news is an incredible motivator. It’s one of the best ways to get people to keep up the fight.

And we need to keep up the fight. Because this isn’t the last time the Fund will need to be replenished.

Nor is it the only organization of this kind that needs money.

In the same way that the Global Fund marshals the worlds resources to fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria, an organization called Gavi does it to vaccinate children – and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative does it to fight polio. Both will need to be replenished over the next year, too.

And we should all be asking: What good is it to save a child from malaria, for them to die of rotavirus? Or measles?

So, here’s the last thing I’ll say: I’ve spent the last year asking many of you – and the countries you represent – for money. (I’m going to keep asking you for that.)

But now I’m also asking all of you for your voices. And to the journalists in the room: I’m asking you for your stories.

In fact, I’ll give you some headlines you can use for free. Here they are:

“Compared to 30 years ago, half the number of children are dying every year – even though the population has shot up by 50 percent!”

Or there’s this: “That the first time the global number of AIDS deaths fell was two years after the founding of the Global Fund – and they’ve fallen every year since.”

Or how about that when this funding kicks in, newspaper editors could run the headline, “Global Fund saves 14,600 lives today” – and they could run that headline every day for the next three years.

Each one of those stories is remarkable. It is true. And don’t forget that it’s true because of your generosity and efforts.

Thank you very much.