Now read this

5 great books for the summer

I loved all of them and hope you’ll find something you enjoy too.

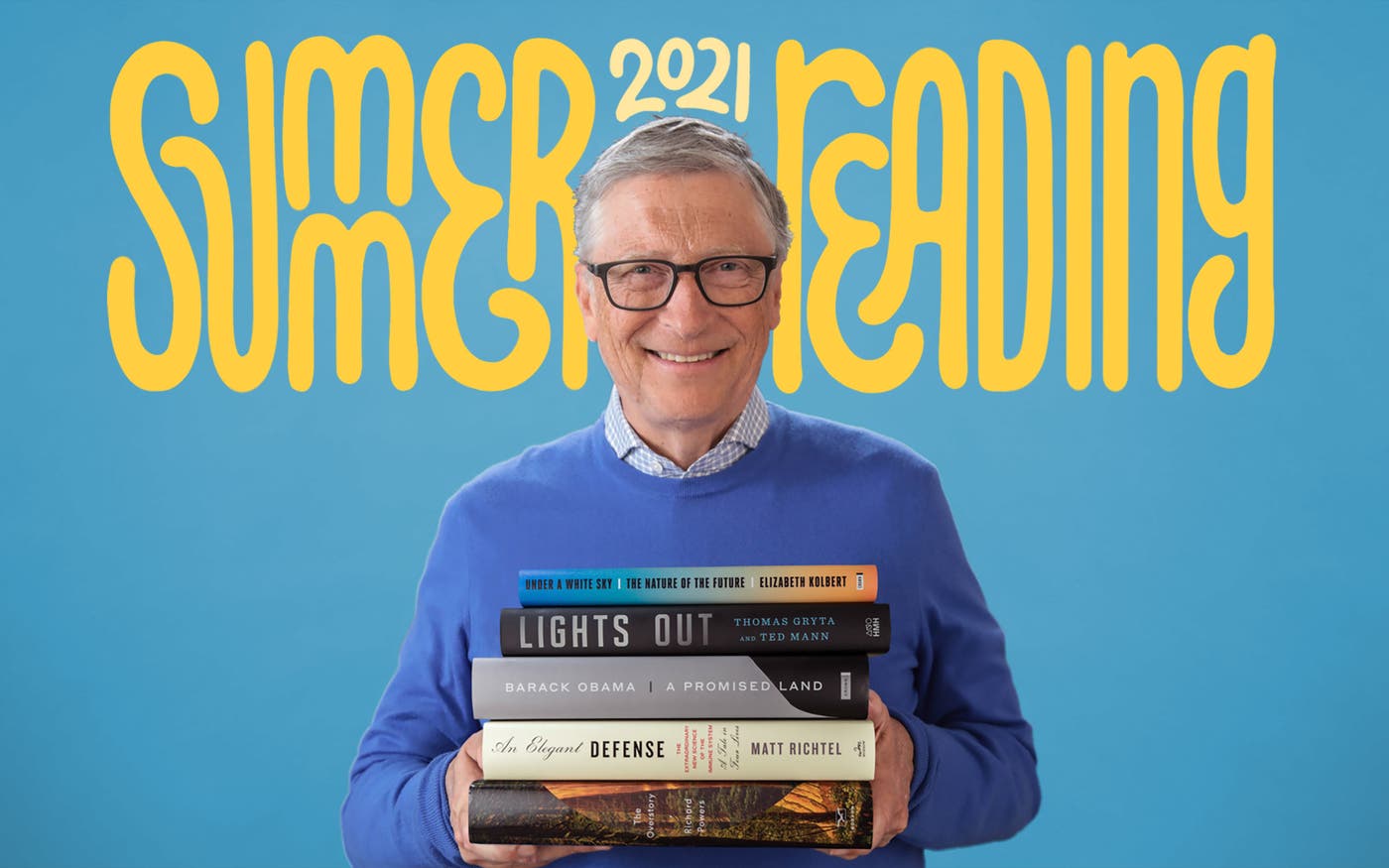

As I was putting together my list of suggested reading for the summer, I realized that the topics they cover sound pretty heavy for vacation reading. There are books here about gender equality, political polarization, climate change, and the hard truth that life never goes the way young people think it will. It does not exactly sound like the stuff of beach reads.

But none of the five books below feel heavy (even though, at nearly 600 pages, The Lincoln Highway is literally weighty). Each of the writers—three novelists, a journalist, and a scientist—was able to take a meaty subject and make it compelling without sacrificing any complexity.

I loved all five of these books and hope you find something here you’ll enjoy too. And feel free to share some of your favorite recent reads in the comments section below.

The Power, by Naomi Alderman. I’m glad that I followed my older daughter’s recommendation and read this novel. It cleverly uses a single idea—what if all the women in the world suddenly gained the power to produce deadly electric shocks from their bodies?—to explore gender roles and gender equality. Reading The Power, I gained a stronger and more visceral sense of the abuse and injustice many women experience today. And I expanded my appreciation for the people who work on these issues in the U.S. and around the world.

Why We’re Polarized, by Ezra Klein. I’m generally optimistic about the future, but one thing that dampens my outlook a bit is the increasing polarization in America, especially when it comes to politics. In this insightful book, Klein argues persuasively that the cause of this split is identity—the human instinct to let our group identities guide our decision making. The book is fundamentally about American politics, but it’s also a fascinating look at human psychology.

The Lincoln Highway, by Amor Towles. I put Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow on my summer books list back in 2019, but I liked this follow-up novel even more. Set in 1954, it’s about two brothers who are trying to drive from Nebraska to California to find their mother; their trip is thrown way off-course by a volatile teenager from the older brother’s past. Towles takes inspiration from famous hero’s journeys and seems to be saying that our personal journeys are never as linear or predictable as we might hope.

The Ministry for the Future, by Kim Stanley Robinson. When I was promoting my book on climate change last year, a number of people told me I should read this novel, because it dramatized many of the issues I had written about. I’m glad I picked it up, because it’s terrific. It’s so complex that it’s hard to summarize, but Robinson presents a stimulating and engaging story, spanning decades and continents, packed with fascinating ideas and people.

How the World Really Works, by Vaclav Smil. Another masterpiece from one of my favorite authors. Unlike most of Vaclav’s books, which read like textbooks and go super-deep on one topic, this one is written for a general audience and gives an overview of the main areas of his expertise. If you want a brief but thorough education in numeric thinking about many of the fundamental forces that shape human life, this is the book to read. It’s a tour de force. Bonus: You can download a free chapter from How the World Really Works on the full review page.

Seasons readings

Five books to read this winter

These were some of my favorite books from 2025.

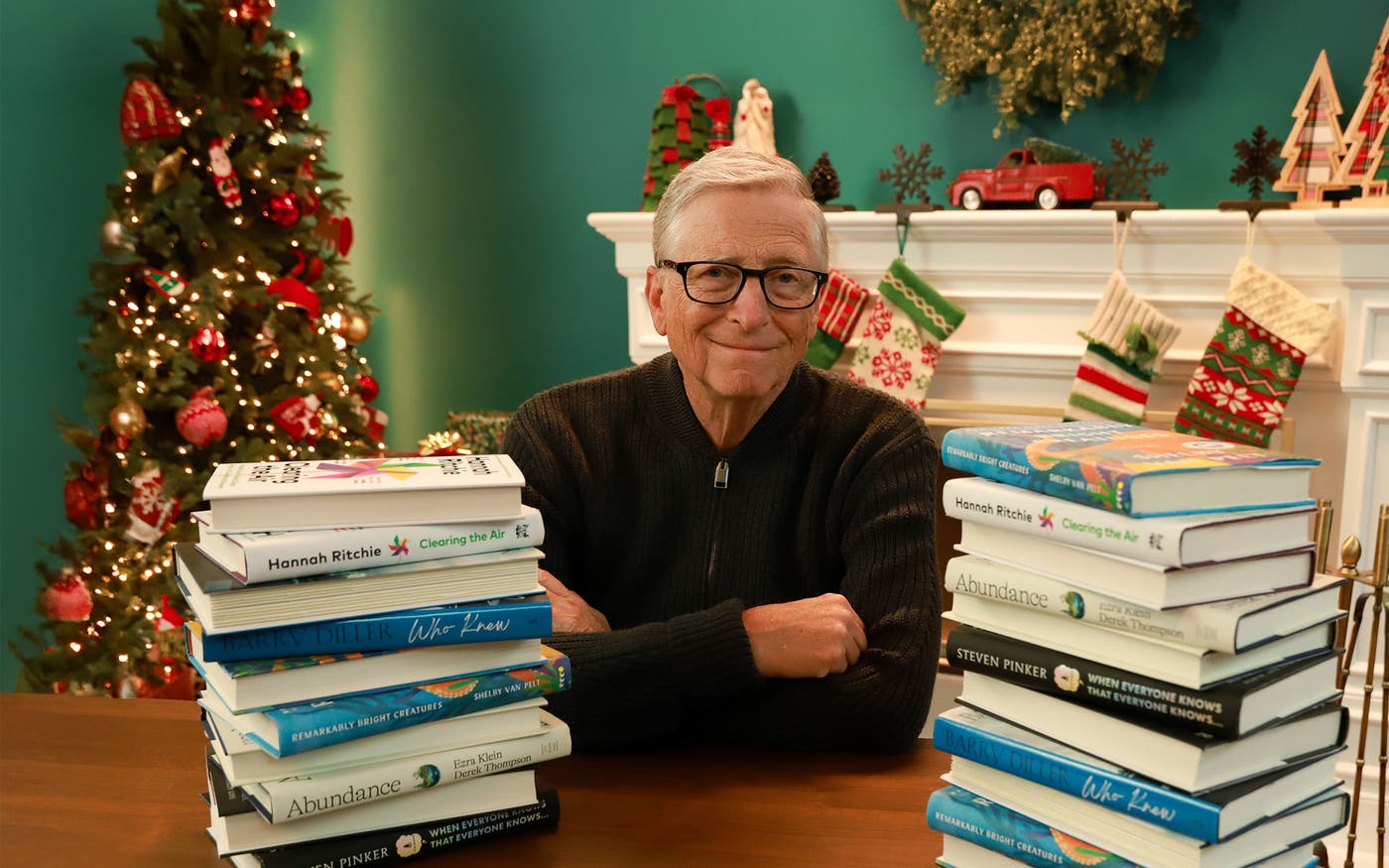

The holidays are almost here. I always love taking advantage of this time of year to catch up on reading, and I know a lot of people feel the same way. There’s something about the quieter days around the holidays that makes it easier to sit down with a good book. So I’m sharing a few recent favorites.

Each of these books pulls back the curtain on how something important really works: how people find purpose later in life, how we should think about climate change, how creative industries evolve, how humans communicate, and how America lost its capacity to build big things—and how to get it back.

I hope you find something here that sparks your curiosity. And I hope your holiday season is filled with happy loved ones, good food, and great conversation.

Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt. I don't read fiction often, but when I do, I want to read about interesting characters who help me see the world in a new way. Remarkably Bright Creatures delivered on that front. I loved this terrific novel about Tova, a 70-year-old woman who works night shifts cleaning an aquarium and finds fulfillment caring for a clever octopus. Tova struggles to find meaning in her life, which is something a lot of people deal with as they get older. Van Pelt's story made me think about the challenge of filling the days after you stop working—and what communities can do to help older people find purpose.

Clearing the Air by Hannah Ritchie. I’ve followed Hannah’s work at Our World in Data for years, and her new book is one of the clearest explanations of the climate challenge I’ve read. She structures it around 50 big questions—like whether it’s too late to act, whether nuclear power is dangerous, and whether renewables really are affordable—and answers each one in concise, accessible language. She’s realistic about the risks but grounded in data that shows real progress: Solar and wind are growing at record speed, electric cars are getting cheaper, and innovation is accelerating across areas like steel, cement, and clean fuels. If you want a hopeful, fact-driven overview of where climate solutions stand, this is a great pick.

Who Knew by Barry Diller. I’ve known Barry for decades, but his memoir still surprised and taught me a lot. He’s one of the most influential figures in modern media. He invented the made-for-TV movie, helped create the TV miniseries, built Paramount into the #1 film studio, launched the Fox broadcast network, and later assembled an internet empire. He’s spent his life betting on ideas before they were obvious, and the industries he’s transformed show how much those bets can pay off.

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows by Steven Pinker. Few people explain the mysteries of human behavior better than Steven Pinker, and his latest book is a must-read for anyone who wants to learn more about how people communicate. When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows shows how “common knowledge” lets people coordinate: When we know what others know, indirect signals become clear. Although the topic itself is pretty complicated, the book is readable and practical, and it made me see everyday social interactions in a new light.

Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. This book is a sharp look at why America seems to struggle to build things and what it will take to fix that. Klein and Thompson argue that progress depends not just on good ideas but on the systems that help ideas spread. Today, these systems often slow things down instead—from housing and infrastructure to clean energy and scientific breakthroughs. I recognized many of the bottlenecks they describe from my own work in global health and climate. Abundance doesn’t pretend to have all the answers, but it asks the right questions about how the U.S. can rebuild our capacity to get big things done.

The source code for Source Code

5 memoirs that helped shape my own

What I learned from other authors who wrote about their lives.

I feel like I’m always learning, but I really go into serious learning mode when I’m starting a new project. In the early days of Microsoft, I read a ton about technology companies, and as I was starting the Gates Foundation, I researched the history of American philanthropy.

Writing my memoir Source Code, which came out earlier this year, was no different: I thought about what I could draw on from the best memoirs I’ve read.

So for this year’s Summer Books, I want to share a few of them. With the exception of Nicholas Kristof’s Chasing Hope, I read all of these before finishing Source Code—in fact I read Katharine Graham’s Personal History years before I even decided to start writing. (Nick’s book is so good that I wanted to share it anyway.)

You won’t find a direct correlation between any of these books and Source Code. But I think it has shades of Bono’s vulnerability about his own challenges, Tara Westover’s evolving view of her parents, and Trevor Noah’s sense as a kid that he didn’t quite fit in.

In any case, I hope you can find something that interests you on this list. Memoirs are a good reminder that people have countless interesting stories to tell about their lives.

Personal History, by Katharine Graham. I met Kay Graham, the legendary publisher of the Washington Post, on July 5, 1991—the same day I met Warren Buffett—and we became good friends. I loved hearing Kay talk about her remarkable life: taking over the Post at a time when few women were in leadership positions like that, standing up to President Nixon to protect the paper’s reporting on Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, negotiating the end to a pressman’s strike, and much more. This thoughtful memoir is a good reminder that great leaders can come from unexpected places.

Chasing Hope, by Nicholas Kristof. In 1997, Nick Kristof wrote an article that changed the course of my life. It was about the huge number of children in poor countries who were dying from diarrhea—and it helped me decide what I wanted to focus my philanthropic giving on. I’ve been following Nick’s work ever since, and we’ve stayed in touch. He’s reported from more than 150 countries, covering war, poverty, health, and human rights. In this terrific memoir, Nick writes about how he stays optimistic about the world despite everything he’s seen. His book made me think: The world would be better off with more Nick Kristofs.

Educated, by Tara Westover. Tara grew up in a Mormon survivalist home in rural Idaho, raised by parents who believed that doomsday was coming and that the family should interact with the outside world as little as possible. Eventually she broke away from her parents—a process that felt like a much more extreme version of what I went through as a kid, and what I think a lot of people go through: At some point in your childhood, you go from thinking your parents know everything to seeing them as adults with limitations. Tara beautifully captures that process of self-discovery in this unforgettable memoir.

Born a Crime, by Trevor Noah. Back in 2017, I said this memoir shows how the former Daily Show host’s “approach has been honed over a lifetime of never quite fitting in.” I also grew up feeling like I didn’t quite fit in at times, although Trevor has a much stronger claim to the phrase than I do. He was a biracial child in apartheid South Africa, a country where mixed-race relationships were forbidden. He was, as the title says, “born a crime.” In this book, and in his comedy, Trevor uses his outside perspective to his advantage. His outlook transcends borders.

Surrender, by Bono. I’m lucky that my parents were super supportive of my interest in computers—but Bono’s parents had a very different view of his passion for singing. He says his parents basically ignored him, which made him try even harder to get their attention. “The lack of interest of my father … in his son’s voice is not easy to explain, but it might have been crucial.” Bono shows a lot of vulnerability in this surprisingly open memoir, writing about his “need to be needed” and how he learned he’ll never fill his emotional needs by playing for huge crowds. It was a great model for how I could be open about my own challenges in Source Code.

Deck the shelves

Books to keep you warm this holiday season

Each book on my list is about making sense of the world around you.

Happy holidays! I hope you and your loved ones are enjoying the coziest time of year—and that you are able to find time to enjoy some good books in between spending time with family.

If you’re in the market for something new to read, I have put together a list of four books I enjoyed this year. All four are, in one way or another, about making sense of the world around you. This wasn’t an intentional theme, but I wasn’t surprised to see it emerge: It’s natural to try and wrap your head around things during times of rapid change, like we’re living through now.

Two of the books on my list focus on the future and how the rise of artificial intelligence and huge technological advances are changing the ways we live, learn, and love. One looks to the past for answers—the lessons it offers about how leaders have tackled tough times before are both comforting and fascinating. And the fourth book on my list is all about the present. It will help you appreciate the amazing, invisible backbone of society that surrounds us every day.

I’ve also thrown in one bonus pick, just in case you are looking for a gift for a tennis lover in your life. You can never have enough books, especially this time of year!

An Unfinished Love Story, by Doris Kearns Goodwin. I’m a huge fan of Doris’s books, but I didn’t know a lot about her personal life until I read her new autobiography. The book focuses on her life with her late husband, who served as a policy expert and speechwriter to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson during one of the most turbulent times in recent U.S. history. Doris is such a talented writer that the chapters about her love story are just as engaging and enlightening as the chapters about the Kennedy assassination and the Vietnam War.

The Anxious Generation, by Jonathan Haidt. This book is a must-read for anyone raising, working with, or teaching young people today. It made me reflect on how much of my younger years—which were often spent running around outside without parental supervision, sometimes getting into trouble—helped shape who I am today. Haidt explains how the shift from play-based childhoods to phone-based childhoods is transforming how kids develop and process emotions. I appreciate that he doesn’t just lay out the problem—he offers real solutions that are worth considering.

Engineering in Plain Sight, by Grady Hillhouse. Have you ever looked at an unusual pipe sticking out of the ground and thought, “What the hell is that?” If so, this is the perfect book for you. Hillhouse takes all of the mysterious structures we see every day, from cable boxes to transformers to cell phone towers, and explains what they are and how they work. It’s the kind of read that will reward your curiosity and answer questions you didn’t even know you had.

The Coming Wave, by Mustafa Suleyman. Mustafa has a deep understanding of scientific history, and he offers the best explanation I’ve seen yet of how artificial intelligence—along with other scientific advances, like gene editing—is poised to reshape every aspect of society. He lays out the risks we need to prepare for and the challenges we need to overcome so we can reap the benefits of these technologies without the dangers. If you want to understand the rise of AI, this is the best book to read.

A bonus read: Federer, by Doris Henkel. This book isn’t for everyone. It’s pretty expensive, and it weighs as much as a small dog. But if you—or someone you love—is a fan of Roger’s, Federer is a wonderful retrospective of his life and career. I thought I knew pretty much everything about Roger’s history with tennis, but I learned a ton, especially about his early years. It includes a lot of photographs I’d never seen before. This is a special treat for the tennis fan in your life.

In service

5 great things to read or watch this summer

I found an unintentional theme connecting them all.

When I finish one book and decide what to read next, there’s rarely a logical connection between the two. I might get to the end of a history book on the Civil War and then pick up a sci-fi novel set in the distant future. The same goes for shows and movies: I gravitate toward whatever sounds most interesting at the moment.

But when I put together a list of recommendations, it’s fun to look back and see if there’s a thread that runs through them. This time, there definitely is.

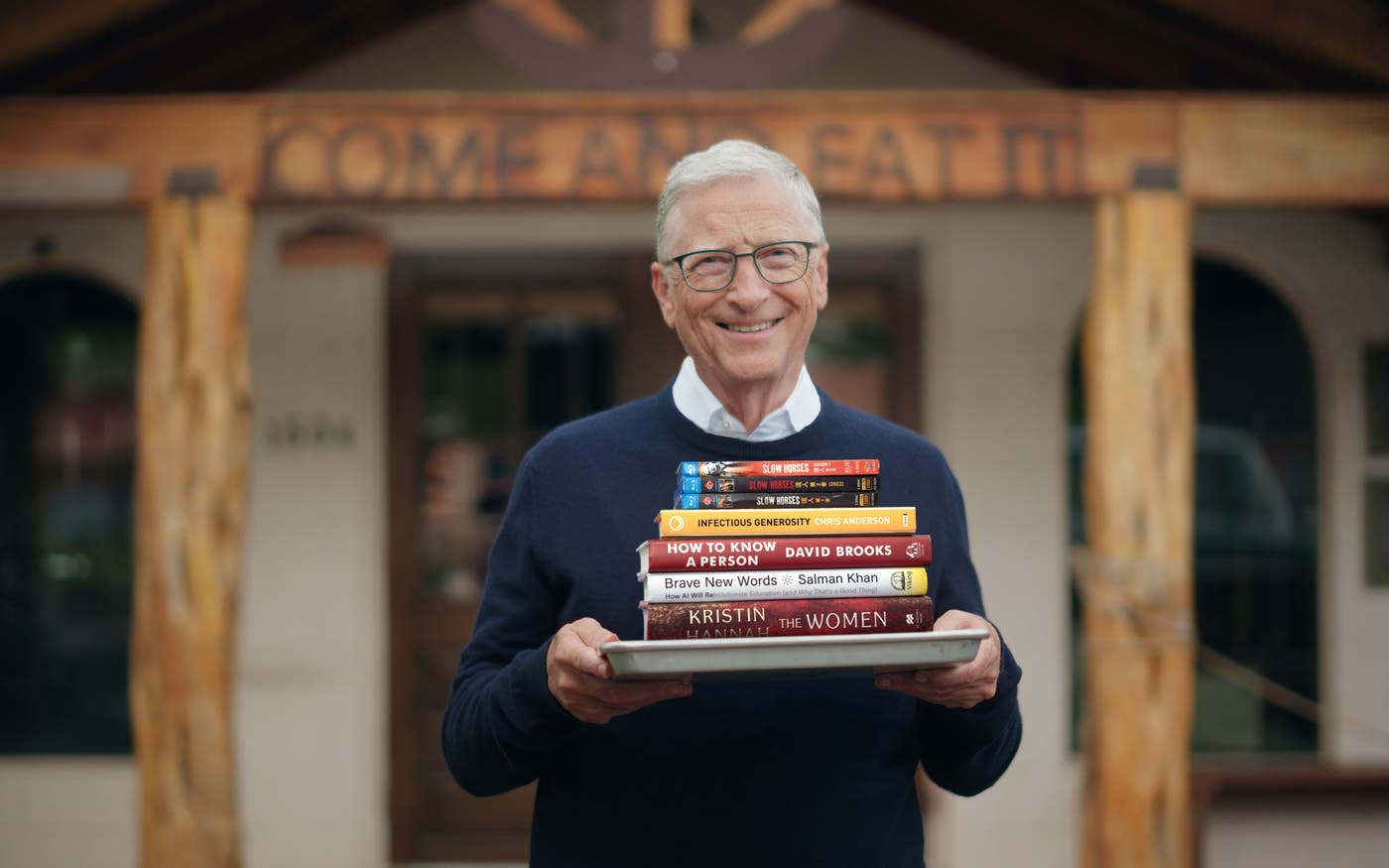

The books and TV series on my summer list all touch on the idea of service to others—why we do it, the things that can make it difficult, and why we should do it anyway. One is a novel about the sacrifices made by American nurses on the front lines of the Vietnam War. Another is a call for (and a guide to) being more generous in the digital age. Others include a rumination on connecting with other people and a look at the evolution of how schoolteachers support their students. Even the TV series is a fictional show about government agents protecting their country.

I didn’t intend to go deep on the idea of service, but it’s certainly as relevant today as ever. At a time when wars dominate the headlines and our politics is becoming more and more polarized, it’s inspiring to appreciate those who help others and think about how we can be more generous in our own lives.

Here’s my list, with links to longer reviews of each entry. Do you ever look back and discover unexpected themes in the things you’ve read, watched, and listened to?

The Women, by Kristin Hannah. This terrific novel tells the story of a U.S. Army nurse who serves two tours on the frontlines in Vietnam before returning home to a country rocked by protest and anti-war sentiment. The author, Kristin Hannah, has written a number of books that did quite well—including this one—and I can see why. It’s a beautifully written tribute to a group of veterans who deserve more appreciation for the incredible sacrifices they made.

Infectious Generosity, by Chris Anderson. Chris, who has been the curator of TED Talks for more than two decades, explores how the internet can amplify the impact of generosity. He offers a plan for how everyone—including individuals, governments, and businesses—can foster more generosity. It’s not just about giving money; he argues that we need to expand our definition of generosity. If you want to help create a more equitable world but don’t know where to start, Infectious Generosity is for you.

Slow Horses. I’m a sucker for stories about spies. I’ve read several of John le Carré’s novels, and two of my favorite movies are Spy Game and Three Days of the Condor. I’d put Slow Horses up there with the best of them. It’s a British series about undercover agents assigned to Slough House, a fictional group inside MI5 where people are sent when they mess up badly, but not quite badly enough to get fired. Gary Oldman plays the head of Slough House, who’s basically the polar opposite of James Bond. He’s a slob and an alcoholic, but then he surprises you with some amazing bit of spycraft. Like le Carré novels, Slow Horses has enough complex characters and plots that you have to really pay attention, but it pays off in the end. (Available in the U.S. on Apple TV+.)

Brave New Words, by Sal Khan. Sal—the founder of Khan Academy—has been a pioneer in the field of education technology since long before the rise of artificial intelligence. So the vision he lays out in Brave New Words for how AI will improve education is well grounded. Sal argues that AI will radically improve both outcomes for students and the experiences of teachers, and help make sure everyone has access to a world-class education. He’s well aware that innovation has had only a marginal impact in the classroom so far but makes a compelling case that AI will be different. No one has sharper insights into the future of education than Sal does, and I can't recommend Brave New Words enough.

How to Know a Person, by David Brooks. I liked David’s previous book, The Road to Character, but this one is even better. His key premise is one I haven't found elsewhere: that conversational and social skills aren't just innate traits—they can be learned and improved upon. And he provides practical tips for what he calls “loud listening,” a practice that can help the people around you feel heard and valued. It’s more than a guide to better conversations; it’s a blueprint for a more connected and humane way of living.

Read, watch, listen

Great books, courses, and music for the holidays

Some favorites from 2023, including a new playlist.

At the end of the year, it’s always fun to look back on some of the best books I read. For 2023, three came to mind right away, each of them deeply informative and well written. I’ve also included economics courses by a phenomenal lecturer that I watched more than a decade ago but am still recommending to friends and family today. Just for fun, I threw in a playlist of great holiday songs from past and present, and from the U.S. and around the world.

I didn’t have time to write up a full review, but I should mention that I just watched the series All the Light We Cannot See on Netflix. I had read the book, which is amazing, sometimes an adaptation of a book you love can be disappointing. That’s not the case here—the series is just as good. The actor who plays von Rumpel, a Nazi gem hunter and the villain in the story, is especially memorable.

I hope you find something fun here to read, watch, or listen to. And happy holidays!

The Song of the Cell, by Siddhartha Mukherjee. All of us will get sick at some point. All of us will have loved ones who get sick. To understand what’s happening in those moments—and to feel optimistic that things will get better—it helps to know something about cells, the building blocks of life. Mukherjee’s latest book will give you that knowledge. He starts by explaining how life evolved from single-celled organisms, and then he shows how every human illness or consequence of aging comes down to something going wrong with the body’s cells. Mukherjee, who’s both an oncologist and a Pulitzer Prize–winning author, brings all of his skills to bear in this fantastic book.

Not the End of the World, by Hannah Ritchie. Hannah Ritchie used to believe—as many environmental activists do—that she was “living through humanity’s most tragic period.” But when she started looking at the data, she realized that’s not the case. Things are bad, and they’re worse than they were in the distant past, but on virtually every measure, they’re getting better. Ritchie is now lead researcher at Our World in Data, and in Not the End of the World, she uses data to tell a counterintuitive story that contradicts the doomsday scenarios on climate and other environmental topics without glossing over the challenges. Everyone who wants to have an informed conversation about climate change should read this book.

Invention and Innovation, by Vaclav Smil. Are we living in the most innovative era of human history? A lot of people would say so, but Smil argues otherwise. In fact, he writes, the current era shows “unmistakable signs of technical stagnation and slowing advances.” I don’t agree, but that’s not surprising—having read all 44 of his books and spoken with him several times, I know he’s not as optimistic as I am about the prospects of innovation. But even though we don’t see the future the same way, nobody is better than Smil at explaining the past. If you want to know how human ingenuity brought us to this moment in time, I highly recommend Invention and Innovation.

Online economics lectures by Timothy Taylor. I’ve watched a lot of lecture series online, and Taylor is one of my favorite professors. All three of his series on Wondrium are fantastic. The New Global Economy teaches you about the basic economic history of different regions and how markets work. Economics is best suited for people who want to understand the principles of economics in a deep way. Unexpected Economics probably has the broadest audience, because Taylor applies those principles to things in everyday life, including gift-giving, traffic, natural disasters, sports, and more. You can’t go wrong with any of Taylor’s lectures.

A holiday playlist. This one doesn’t need much explanation. I love holiday music and have put together a list of some favorites—classics and modern tunes, from the U.S. and around the world.

Read, watch, and listen

Great books, songs, and shows for the summer

Because there’s more to life than reading. (Though reading is still the best.)

For the past decade, I’ve recommended great books to read each summer. This year, I decided to mix it up and try something different. I’m recommending just two books—one novel and one nonfiction—plus a mix of other things I’ve enjoyed lately, including a TV series set in Denmark and a few dozen songs that are on regular rotation for me. Whatever your summer plans are, I hope you find something here to help you make the most of them.

Books

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, by Gabrielle Zevin. This terrific novel tells the story of two friends who grow up bonding over Super Mario Bros. and then, in college, start making their own games together. I really related to the story—in fact, it reminded me a lot of my relationship with Paul Allen and our work together at Microsoft. Tomorrow was one of the biggest books of last year, and it’s easy to see why. Zevin is a great writer who makes you care deeply about her characters.

Born in Blackness, by Howard French. I’m a student of Africa, but I still learned a lot from this thoughtful, well-researched book. French, a journalist of African descent, challenges the standard Western accounts of the continent’s history. It was far from stateless and primitive when Europeans arrived. In reality, he explains, various African kingdoms had established city-states that rivaled Europe’s in terms of political organization, military power, commerce, art, and exploration. I mean it as a compliment when I say that Born in Blackness left me wanting to know more.

TV

Borgen (available on Netflix in the U.S.). I’ve binged all four seasons of this Danish political drama. Named for the palace in Copenhagen where the Danish government is based, it follows the country’s (fictional) first female prime minister as she navigates a complex political landscape. I’m fascinated by how political coalitions come together and stay together, and I loved watching the PM, Birgitte Nyborg, figure it all out. She’s a principled and talented leader who’s also fallible and sometimes misguided. Borgen is entertaining above all else, but I’ve learned a ton from watching it too.

My summer playlist

Here’s a Spotify playlist with many of my favorite tracks—songs newer and older that have stuck with me over the years. You’ll find everything from Billie Holiday, Nat King Cole, and the Beatles to Vampire Weekend, Adele, and U2.

Page turners

5 of my all-time favorite books

I decided to try something different for my list of holiday books this year.

The holidays are a great time for annual traditions. Like many people, I love to spend the end of the year celebrating the holidays with my family. (We usually wear matching pajamas on Christmas.) I also enjoy sitting down to write my annual list of holiday books, which I’ve done around this time of year for the last decade. It’s always a fun opportunity for me to reflect on everything I’ve read recently.

This time, though, I decided to try something different. Rather than limit myself to things I’ve read over the previous twelve months, I instead picked books regardless of when I finished them.

One of the selections has been a favorite of mine since middle school. Another is a brand-new memoir that I just finished. This isn’t a complete list of my favorite books of all time—that list would include a lot more Vaclav Smil and Elizabeth Kolbert. But all five are books that I have recommended to my family and friends over the years.

I hope you find something new to read this winter—and that you and your loved ones enjoy celebrating your favorite traditions together over the holiday season.

Best introduction to grownup sci-fi: Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert Heinlein. Paul Allen and I fell in love with Heinlein when we were just kids, and this book is still one of my favorite sci-fi novels of all time. It tells the story of a young man who returns to Earth after growing up on Mars and starts a new religion. I think the best science fiction pushes your thinking about what’s possible in the future, and Heinlein managed to predict the rise of hippie culture years before it emerged.

Best memoir by a rock star: Surrender, by Bono. This book came out this month, so it’s the most recent one I’ve read on my list. If you’re a U2 fan, there is a good chance you already plan to check it out. Even if you’re not, it’s a super fun read about how a boy from the suburbs of Dublin grew up to become a world-famous rock star and philanthropist. I’m lucky enough to call Bono a friend, but a lot of the stories he tells in Surrender were new to me.

Best guide to leading a country: Team of Rivals, by Doris Kearns Goodwin. I can’t read enough about Abraham Lincoln, and this is one of the best books on the subject. It feels especially relevant now when our country is once again facing violent insurrection, difficult questions about race, and deep ideological divides. Goodwin is one of America’s best biographers, and Team of Rivals is arguably her masterpiece.

Best guide to getting out of your own way: The Inner Game of Tennis, by Timothy Gallwey. This book from 1974 is a must-read for anyone who plays tennis, but I think even people who have never played will get something out of it. Gallwey argues that your state of mind is just as important—if not more important—than your physical fitness. He gives excellent advice about how to move on constructively from mistakes, which I’ve tried to follow both on and off the court over the years.

Best book about the periodic table: Mendeleyev’s Dream, by Paul Strathern. The history of chemistry is filled with quirky characters like Dimitri Mendeleyev, the Russian scientist who first proposed the periodic table after it allegedly came to him in a dream. Strathern’s book traces that history all the way back to its origins in ancient Greece. It’s a fascinating look at how science develops and how human curiosity has evolved over the millennia.

Cover to cover

5 books I loved reading this year

Lately, I’ve found myself drawn to the kinds of books I would’ve liked as a kid.

When I was a kid, I was obsessed with science fiction. Paul Allen and I would spend countless hours discussing Isaac Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy. I read every book by Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert Heinlein. (The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress was a particular favorite.) There was something so thrilling to me about these stories that pushed the limits of what was possible.

As I got older, I started reading a lot more non-fiction. I was still interested in books that explored the implications of innovation, but it felt more important to learn something about our real world along the way. Lately, though, I’ve found myself drawn back to the kinds of books I would’ve loved as a kid.

My holiday reading list this year includes two terrific science fiction stories. One takes place nearly 12 light-years away from our sun, and the other is set right here in the United States—but both made me think about how people can use technology to respond to challenges. I’ve also included a pair of non-fiction books about cutting-edge science and a novel that made me look at one of history’s most famous figures in a new light.

I read a lot of great books this year—including John Doerr’s latest about climate change—but these were some of my favorites.

A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, by Jeff Hawkins. Few subjects have captured the imaginations of science fiction writers like artificial intelligence. If you’re interested in learning more about what it might take to create a true AI, this book offers a fascinating theory. Hawkins may be best known as the co-inventor of the PalmPilot, but he’s spent decades thinking about the connections between neuroscience and machine learning, and there’s no better introduction to his thinking than this book.

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, by Walter Isaacson. The CRISPR gene editing system is one of the coolest and perhaps most consequential scientific breakthroughs of the last decade. I’m familiar with it because of my work at the foundation—we’re funding a number of projects that use the technology—but I still learned a lot from this comprehensive and accessible book about its discovery by Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues. Isaacson does a good job highlighting the most important ethical questions around gene editing.

Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro. I love a good robot story, and Ishiguro’s novel about an “artificial friend” to a sick young girl is no exception. Although it takes place in a dystopian future, the robots aren’t a force for evil. Instead, they serve as companions to keep people company. This book made me think about what life with super intelligent robots might look like—and whether we’ll treat these kinds of machines as pieces of technology or as something more.

Hamnet, by Maggie O’Farrell. If you’re a Shakespeare fan, you’ll love this moving novel about how his personal life might’ve influenced the writing of one of his most famous plays. O’Farrell has built her story on two facts we know to be true about “The Bard”: his son Hamnet died at the age of 11, and a couple years later, Shakespeare wrote a tragedy called Hamlet. I especially enjoyed reading about his wife, Anne, who is imagined here as an almost supernatural figure.

Project Hail Mary, by Andy Weir. Like most people, I was first introduced to Weir’s writing through The Martian. His latest novel is a wild tale about a high school science teacher who wakes up in a different star system with no memory of how he got there. The rest of the story is all about how he uses science and engineering to save the day. It’s a fun read, and I finished the whole thing in one weekend.

Good reads

5 ideas for summer reading

These books gave me something to think about. I hope they do the same for you.

When I finish one book and am deciding what to read next, there usually isn’t always rhyme or reason to what I pick. Sometimes I’ll read one great book and get inspired to read several more about the same subject. Other times I am eager to follow a recommendation from someone I respect.

Lately, though, I find myself reaching for books about the complicated relationship between humanity and nature. Maybe it’s because everyone’s lives have been upended by a virus. Or maybe it’s because I’ve spent so much time this year talking about what we need to do to avoid a climate disaster.

Whatever the reason, most of the books on my summer reading list this year touch on what happens when people come into conflict with the world around them. I’ve included a look at how researchers are trying to undo damage done to the planet by humans, a deep dive about how your body keeps you safe from microscopic invaders, a president’s memoir that addresses the fallout from an oil spill, and a novel about a group of ordinary people fighting to save the trees. (There’s also a fascinating look at the downfall of one of America’s greatest companies.)

I hope at least one of these books sparks your interest this summer.

Lights Out: Pride, Delusion, and the Fall of General Electric, by Thomas Gryta and Ted Mann. How could a company as big and successful as GE fail? I’ve been thinking about that question for several years, and Lights Out finally gave me many of the answers I was seeking. The authors give you an unflinching look at the mistakes and missteps made by GE’s leadership. If you’re in any kind of leadership role—whether at a company, a non-profit, or somewhere else—there’s a lot you can learn here.

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future, by Elizabeth Kolbert. Kolbert’s latest is the most straightforward examination of “humanity versus nature” on this list. She describes it as “a book about people trying to solve problems caused by people trying to solve problems.” She writes about a number of the ways that people are intervening with nature, including gene drive and geoengineering—two topics that I’m particularly interested in. Like all of her books, it’s an enjoyable read.

A Promised Land, by Barack Obama. I am almost always interested in books about American presidents, and I especially loved A Promised Land. The memoir covers his early career up through the mission that killed Osama bin Laden in 2011. President Obama is unusually honest about his experience in the White House, including how isolating it is to be the person who ultimately calls the shots. It’s a fascinating look at what it’s like to steer a country through challenging times.

The Overstory, by Richard Powers. This is one of the most unusual novels I’ve read in years. The Overstory follows the lives of nine people and examines their connection with trees. Some of the characters come together over the course of the book, while others stay on their own. Even though the book takes a pretty extreme view towards the need to protect forests, I was moved by each character’s passion for their cause and finished the book eager to learn more about trees.

An Elegant Defense: The Extraordinary New Science of the Immune System: A Tale in Four Lives, by Matt Richtel. Richtel wrote his book before the pandemic, but this exploration of the human immune system is nevertheless a valuable read that will help you understand what it takes to stop COVID-19. He keeps the subject accessible by focusing on four patients, each of whom is forced to manage their immune system in one way or another. Their stories make for a super interesting look at the science of immunity.

Holiday books 2020

5 good books for a lousy year

In a year like this, sometimes you want to go deep on a tough issue. Other times you need a break.

In tough times—and there’s no doubt that 2020 qualifies as tough times—those of us who love to read turn to all kinds of different books. This year, sometimes I chose to go deeper on a difficult subject, like the injustices that underlie this year’s Black Lives Matter protests. Other times I needed a change of pace, something lighter at the end of the day. As a result, I read a wide range of books, and a lot of excellent ones. Here are five books on a variety of subjects that I’d recommend as we wrap up 2020. I hope you find something that helps you—or the book lover in your life—finish the year on a good note.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander. Like many white people, I’ve tried to deepen my understanding of systemic racism in recent months. Alexander’s book offers an eye-opening look into how the criminal justice system unfairly targets communities of color, and especially Black communities. It’s especially good at explaining the history and the numbers behind mass incarceration. I was familiar with some of the data, but Alexander really helps put it in context. I finished the book more convinced than ever that we need a more just approach to sentencing and more investment in communities of color.

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, by David Epstein. I started following Epstein’s work after watching his fantastic 2014 TED talk on sports performance. In this fascinating book, he argues that although the world seems to demand more and more specialization—in your career, for example—what we actually need is more people “who start broad and embrace diverse experiences and perspectives while they progress.” His examples run from Roger Federer to Charles Darwin to Cold War-era experts on Soviet affairs. I think his ideas even help explain some of Microsoft’s success, because we hired people who had real breadth within their field and across domains. If you’re a generalist who has ever felt overshadowed by your specialist colleagues, this book is for you.

The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, by Erik Larson. Sometimes history books end up feeling more relevant than their authors could have imagined. That’s the case with this brilliant account of the years 1940 and 1941, when English citizens spent almost every night huddled in basements and Tube stations as Germany tried to bomb them into submission. The fear and anxiety they felt—while much more severe than what we’re experiencing with COVID-19—sounded familiar. Larson gives you a vivid sense of what life was like for average citizens during this awful period, and he does a great job profiling some of the British leaders who saw them through the crisis, including Winston Churchill and his close advisers. Its scope is too narrow to be the only book you ever read on World War II, but it’s a great addition to the literature focused on that tragic period.

The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War, by Ben Macintyre. This nonfiction account focuses on Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB officer who became a double agent for the British, and Aldrich Ames, the American turncoat who likely betrayed him. Macintyre’s retelling of their stories comes not only from Western sources (including Gordievsky himself) but also from the Russian perspective. It’s every bit as exciting as my favorite spy novels.

Breath from Salt: A Deadly Genetic Disease, a New Era in Science, and the Patients and Families Who Changed Medicine, by Bijal P. Trivedi. This book is truly uplifting. It documents a story of remarkable scientific innovation and how it has improved the lives of almost all cystic fibrosis patients and their families. This story is especially meaningful to me because I know families who’ve benefited from the new medicines described in this book. I suspect we’ll see many more books like this in the coming years, as biomedical miracles emerge from labs at an ever-greater pace.

Great escapes

5 summer books and other things to do at home

Whether you’re looking for a distraction or just spending a lot more time at home, you can’t beat reading a book.

Most of my conversations and meetings these days are about COVID-19 and how we can stem the tide. But I’m also often asked about what I am reading and watching—either because people want to learn more about pandemics, or because they are looking for a distraction. I’m always happy to talk about great books and TV shows (and to hear what other people are doing, since I’m usually in the market for recommendations).

So, in addition to the five new book reviews I always write for my summer book list, I included a number of other recommendations. I hope you find something that catches your interest.

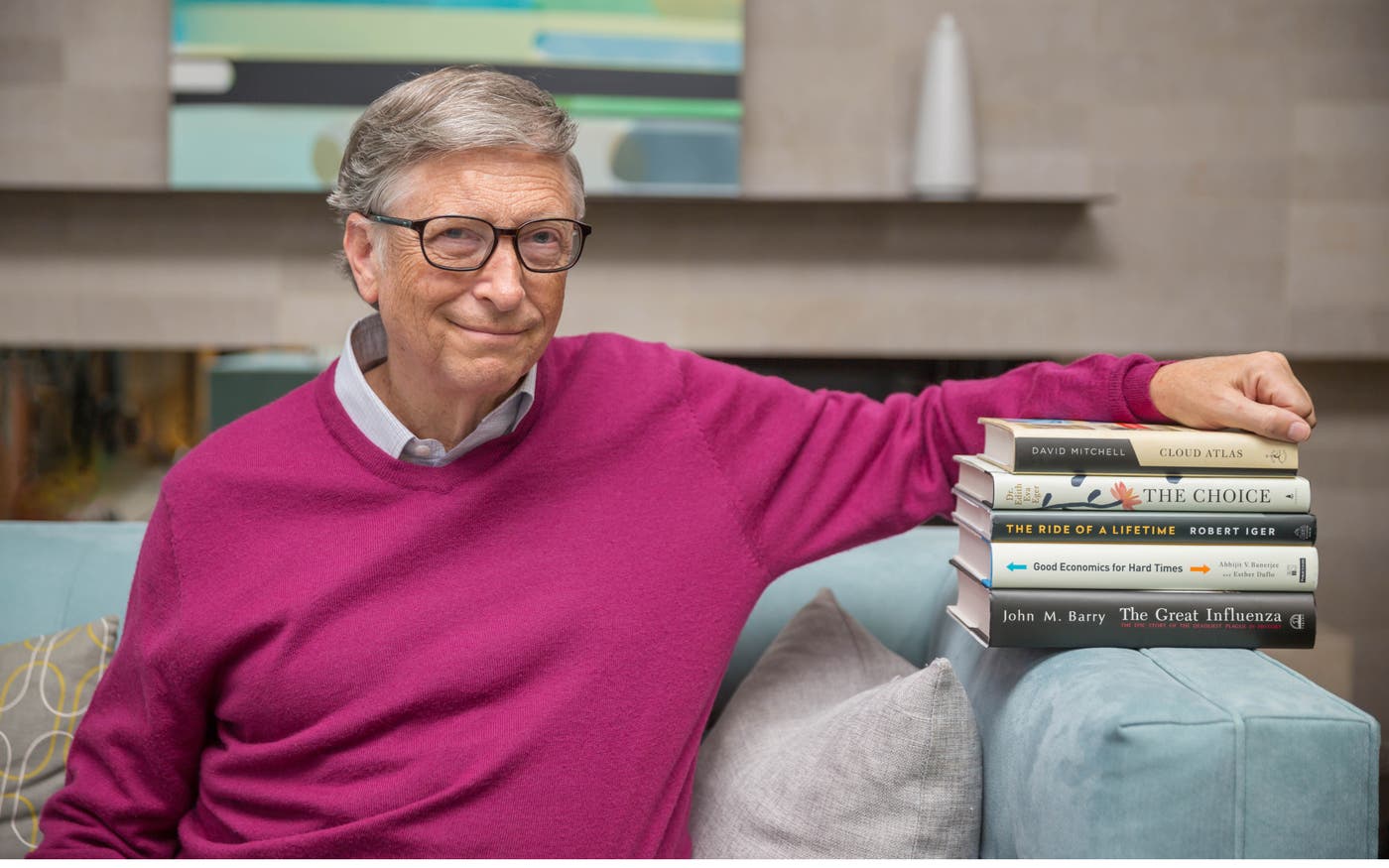

My 2020 summer book recommendations

The Choice, by Dr. Edith Eva Eger. This book is partly a memoir and partly a guide to processing trauma. Eger was only sixteen years old when she and her family got sent to Auschwitz. After surviving unbelievable horrors, she moved to the United States and became a therapist. Her unique background gives her amazing insight, and I think many people will find comfort right now from her suggestions on how to handle difficult situations.

Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell. This is the kind of novel you’ll think and talk about for a long time after you finish it. The plot is a bit hard to explain, because it involves six inter-related stories that take place centuries apart (including one I particularly loved about a young American doctor on a sailing ship in the South Pacific in the mid-1800s). But if you’re in the mood for a really compelling tale about the best and worst of humanity, I think you’ll find yourself as engrossed in it as I was.

The Ride of a Lifetime, by Bob Iger. This is one of the best business books I’ve read in several years. Iger does a terrific job explaining what it’s really like to be the CEO of a large company. Whether you’re looking for business insights or just an entertaining read, I think anyone would enjoy his stories about overseeing Disney during one of the most transformative times in its history.

The Great Influenza, by John M. Barry. We’re living through an unprecedented time right now. But if you’re looking for a historical comparison, the 1918 influenza pandemic is as close as you’re going to get. Barry will teach you almost everything you need to know about one of the deadliest outbreaks in human history. Even though 1918 was a very different time from today, The Great Influenza is a good reminder that we’re still dealing with many of the same challenges.

Good Economics for Hard Times, by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo. Banerjee and Duflo won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences last year, and they’re two of the smartest economists working today. Fortunately for us, they’re also very good at making economics accessible to the average person. Their newest book takes on inequality and political divisions by focusing on policy debates that are at the forefront in wealthy countries like the United States.

Other books worth reading

The Headspace Guide to Meditation and Mindfulness, by Andy Puddicombe. For years, I was a skeptic about meditation. Now I do it as often as I can—three times a week, if time allows. Andy’s book and the app he created, Headspace, are what made me a convert. Andy, a former Buddhist monk, offers lots of helpful metaphors to explain potentially tricky concepts in meditation. At a time when we all could use a few minutes to de-stress and re-focus each day, this is a great place to start.

Moonwalking with Einstein, by Joshua Foer. If you’re looking to work on a new skill, you could do worse than learning to memorize things. Foer is a science writer who got interested in how memory works, and why some people seem to have an amazing ability to recall facts. He takes you inside the U.S. Memory Championship—yes, that’s a real thing—and introduces you to the techniques that, amazingly, allowed him to win the contest one year.

The Martian, by Andy Weir. You may remember the movie from a few years ago, when Matt Damon—playing a botanist who’s been stranded on Mars—sets aside his fear and says, “I’m going to science the s*** out of this.” We’re doing the same thing with the novel coronavirus.

A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles. The main character in this novel is living through a situation that now feels very relatable: He can’t leave the building he’s living in. But he’s not stuck there because of a disease; it’s 1922, and he’s a Russian count who’s serving a life sentence under house arrest in a hotel. I thought it was a fun, clever, and surprisingly upbeat story about making the best of your surroundings.

The Rosie Trilogy, by Graeme Simsion. All three of the Rosie novels made me laugh out loud. They’re about a genetics professor with Asperger’s Syndrome who (in the first book) goes looking for a wife and then (in the second and third books) starts a family. Ultimately the story is about getting inside the mind and heart of someone a lot of people see as odd, and discovering that he isn’t really that different from anybody else. Melinda got me started on these books, and I’m glad she did.

I don’t read a lot of comics or graphic novels, but I’ve really enjoyed the few that I have picked up. The best ones combine amazing storytelling with striking visuals. In her memoir The Best We Could Do, for example, Thi Bui gains a new appreciation for what her parents—who survived the Vietnam War—went through. It’s a deeply personal book that explores what it means to be a parent and a refugee.

On the lighter side is Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things that Happened, by Allie Brosh. You will rip through it in three hours, tops. But you’ll wish it went on longer, because it’s funny and smart as hell. I must have read Melinda a dozen hilarious passages out loud.

Finally, I love the way that former NASA engineer Randall Munroe turns offbeat science lessons into super-engaging comics. The two books of his that I’ve read and highly recommend are What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions, and XKCD Volume 0. I also have Randall’s latest book, How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems, on my bookshelf and hope to read it soon. If you’ve read it, let me know what you think in the comments.

TV shows and movies you might enjoy

Pandemic: How to Prevent an Outbreak. This documentary series on Netflix introduces you to four people who are working super-hard in different parts of the world to prevent epidemics. Since the series was filmed some time ago, the episodes are focused not on the coronavirus but on influenza—which was widely regarded as the most likely culprit for a big outbreak. But Pandemic still gives you a sense of the inspiring work that heroic doctors, researchers, and aid workers are doing to prevent the very thing we’re all going through right now.

A few of the series that Melinda and I are keeping up with include A Million Little Things, This Is Us, and Ozark. And I’m planning to finally watch I, Claudius—a 1970s BBC series set during the Roman empire—after reading a rave review in The Economist. I’ve read a lot about the Roman times, but this series sounds like an interesting look at the era.

On the much more escapist front, a few weeks ago I re-watched one of my favorite movies, Spy Game, starring Robert Redford and Brad Pitt. It has lots of good surprises, so I don’t want to spoil the plot for you. Not a lot of people have heard of Spy Game, but I’ve probably seen it 12 times.

I’ve made lists of these books and shows on Likewise.

The wild card: online bridge

I’ve been playing bridge for years—Warren Buffett is my favorite partner. We don’t get together in person now that we’re sheltering in place, but we still play online. There are lots of great options out there, including this guide to learning the game, and the online platform that Warren and I play on, which is called Bridge Base. (I'll keep our screen names between us.) I got worried a couple months ago when their service briefly went down, but it was back up in no time. I was surprised at how relieved I was to see it running again.

Escapes from the cold

5 books to enjoy this winter

The five books on my end-of-year list will help you start 2020 on a good note.

As the clock ticks closer to midnight on New Year’s Eve, it’s fun to look back at what you’ve accomplished this year. December is a great time to take stock of everything you’ve done over the last twelve months—including all of the books you’ve read.

Because I’m a data guy, I like to look at my reading list and see if any trends emerge. This year, I picked up a bit more fiction than usual. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but I seemed to be drawn to stories that let me explore another world.

I’m currently trying to finish Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell before the end of the year (it’s amazingly clever but a bit hard to follow). Along with A Gentleman in Moscow and An American Marriage, I finished The Rosie Result by Graeme Simsion and a terrific novel about a woman who deals with grief by bonding with a Great Dane. I even picked up a short story collection in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men.

Maybe next year’s end-of-year books post will finally include the Wallace novel I’ve been wanting to read for a while: Infinite Jest.

For this year’s holiday books list, I chose five titles that I think you’ll also enjoy reading. I think they’re all solid choices to help wrap up your 2019 or start 2020 on a good note:

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones. My daughter Jenn recommended that I read this novel, which tells the story of a black couple in the South whose marriage gets torn apart by a horrible incident of injustice. Jones is such a good writer that she manages to make you empathize with both of her main characters, even after one makes a difficult decision. The subject matter is heavy but thought-provoking, and I got sucked into Roy and Celestial’s tragic love story.

These Truths, by Jill Lepore. Lepore has pulled off the seemingly impossible in her latest book: covering the entire history of the United States in just 800 pages. She’s made a deliberate choice to make diverse points of view central to the narrative, and the result is the most honest and unflinching account of the American story I’ve ever read. Even if you’ve read a lot about U.S. history, I’m confident you will learn something new from These Truths.

Growth, by Vaclav Smil. When I first heard that one of my favorite authors was working on a new book about growth, I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it. (Two years ago, I wrote that I wait for new Smil books the way some people wait for the next Star Wars movie. I stand by that statement.) His latest doesn’t disappoint. As always, I don’t agree with everything Smil says, but he remains one of the best thinkers out there at documenting the past and seeing the big picture.

Prepared, by Diane Tavenner. As any parent knows, preparing your kids for life after high school is a long and sometimes difficult journey. Tavenner—who created a network of some of the best performing schools in the nation—has put together a helpful guidebook about how to make that process as smooth and fruitful as possible. Along the way, she shares what she’s learned about teaching kids not just what they need to get into college, but how to live a good life.

Why We Sleep, by Matthew Walker. I read a couple of great books this year about human behavior, and this was one of the most interesting and profound. Both Jenn and John Doerr urged me to read it, and I’m glad I did. Everyone knows that a good night’s sleep is important—but what exactly counts as a good night’s sleep? And how do you make one happen? Walker has persuaded me to change my bedtime habits to up my chances. If your New Year’s resolution is to be healthier in 2020, his advice is a good place to start.

Here comes the sun

Looking for a summer read? Try one of these 5 books

I can’t recommend these books highly enough.

I always like to pick out a bunch of books to bring with me whenever I get ready to go on vacation. More often than not, I end up taking more books than I could possibly read on one trip. My philosophy is that I’d rather have too much to read on a trip than too little.

If you’re like me, you’re probably starting to think about what’s on your summer reading list this year—and I can’t recommend the books below highly enough.

None of them are what most people think of as a light read. All but one deal with the idea of disruption, but I don’t mean “disruption” in the way tech people usually mean it. I’ve recently found myself drawn to books about upheaval (that’s even the title of the one of them)—whether it’s the Soviet Union right after the Bolshevik revolution, the United States during times of war, or a global reevaluation of our economic system.

If you’re looking for something that’s more of a typical summer book, I recommend Graeme Simsion’s The Rosie Result. (And if you haven’t read the first two books in the Rosie trilogy, summer vacation is the perfect time to start!) I also can’t resist a plug for Melinda’s new book The Moment of Lift. I know I’m biased, but it’s one of the best books I’ve read so far this year.

Here is my full summer reading list:

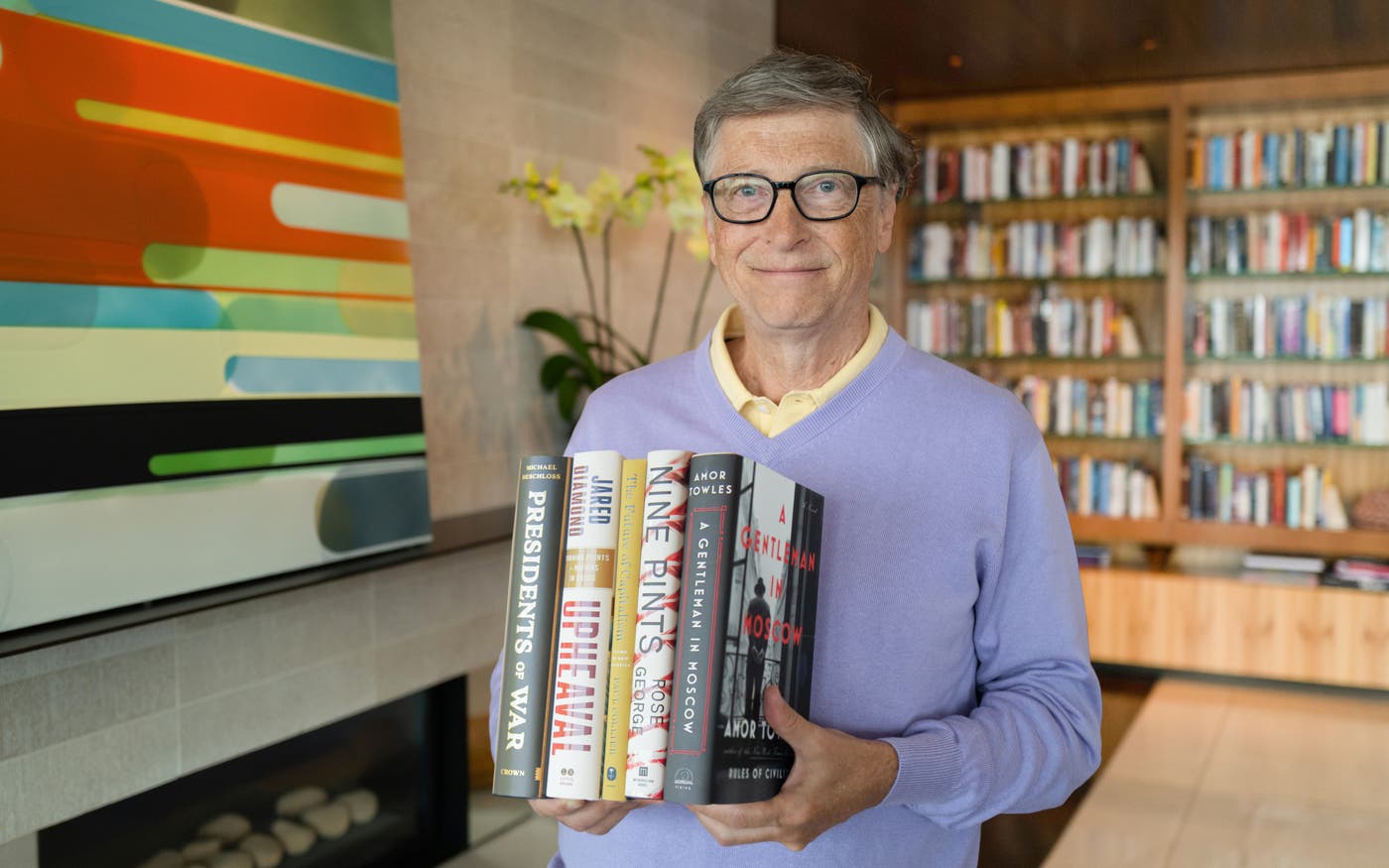

Upheaval, by Jared Diamond. I’m a big fan of everything Jared has written, and his latest is no exception. The book explores how societies react during moments of crisis. He uses a series of fascinating case studies to show how nations managed existential challenges like civil war, foreign threats, and general malaise. It sounds a bit depressing, but I finished the book even more optimistic about our ability to solve problems than I started.

Nine Pints, by Rose George. If you get grossed out by blood, this one probably isn’t for you. But if you’re like me and find it fascinating, you’ll enjoy this book by a British journalist with an especially personal connection to the subject. I’m a big fan of books that go deep on one specific topic, so Nine Pints (the title refers to the volume of blood in the average adult) was right up my alley. It’s filled with super-interesting facts that will leave you with a new appreciation for blood.

A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles. It seems like everyone I know has read this book. I finally joined the club after my brother-in-law sent me a copy, and I’m glad I did. Towles’s novel about a count sentenced to life under house arrest in a Moscow hotel is fun, clever, and surprisingly upbeat. Even if you don’t enjoy reading about Russia as much as I do (I’ve read every book by Dostoyevsky), A Gentleman in Moscow is an amazing story that anyone can enjoy.

Presidents of War, by Michael Beschloss. My interest in all aspects of the Vietnam War is the main reason I decided to pick up this book. By the time I finished it, I learned a lot not only about Vietnam but about the eight other major conflicts the U.S. entered between the turn of the 19th century and the 1970s. Beschloss’s broad scope lets you draw important cross-cutting lessons about presidential leadership.

The Future of Capitalism, by Paul Collier. Collier’s latest book is a thought-provoking look at a topic that’s top of mind for a lot of people right now. Although I don’t agree with him about everything—I think his analysis of the problem is better than his proposed solutions—his background as a development economist gives him a smart perspective on where capitalism is headed.

The greatest gift of all

5 books I loved in 2018

There’s something for everyone on my end-of-year book list.

If you’re like me, you love giving—or getting!—books during the holidays. A great read is the perfect gift: thoughtful and easy to wrap (with no batteries or assembly required). Plus, I think everyone could use a few more books in their lives. I usually don’t consider whether something would make a good present when I’m putting together my end of year book list—but this year’s selections are highly giftable.

My list is pretty eclectic this year. From a how-to guide about meditation to a deep dive on autonomous weapons to a thriller about the fall of a once-promising company, there’s something for everyone. If you’re looking for a fool-proof gift for your friends and family, you can’t go wrong with one of these.

Educated, by Tara Westover. Tara never went to school or visited a doctor until she left home at 17. I never thought I’d relate to a story about growing up in a Mormon survivalist household, but she’s such a good writer that she got me to reflect on my own life while reading about her extreme childhood. Melinda and I loved this memoir of a young woman whose thirst for learning was so strong that she ended up getting a Ph.D. from Cambridge University.

Army of None, by Paul Scharre. Autonomous weapons aren’t exactly top of mind for most around the holidays, but this thought-provoking look at A.I. in warfare is hard to put down. It’s an immensely complicated topic, but Scharre offers clear explanations and presents both the pros and cons of machine-driven warfare. His fluency with the subject should come as no surprise: he’s a veteran who helped draft the U.S. government’s policy on autonomous weapons.

Bad Blood, by John Carreyrou. A bunch of my friends recommended this one to me. Carreyrou gives you the definitive insider’s look at the rise and fall of Theranos. The story is even crazier than I expected, and I found myself unable to put it down once I started. This book has everything: elaborate scams, corporate intrigue, magazine cover stories, ruined family relationships, and the demise of a company once valued at nearly $10 billion.

21 Lessons for the 21st Century, by Yuval Noah Harari. I’m a big fan of everything Harari has written, and his latest is no exception. While Sapiens and Homo Deus covered the past and future respectively, this one is all about the present. If 2018 has left you overwhelmed by the state of the world, 21 Lessons offers a helpful framework for processing the news and thinking about the challenges we face.

The Headspace Guide to Meditation and Mindfulness, by Andy Puddicombe. I’m sure 25-year-old me would scoff at this one, but Melinda and I have gotten really into meditation lately. The book starts with Puddicombe’s personal journey from a university student to a Buddhist monk and then becomes an entertaining explainer on how to meditate. If you’re thinking about trying mindfulness, this is the perfect introduction.

Big questions

5 books worth reading this summer

Five titles you might enjoy over the next few months.

I’ve read some terrific books lately. When I pulled together this list of five that you might enjoy this summer, I realized that several of my choices wrestle with big questions. What makes a genius tick? Why do bad things happen to good people? Where does humanity come from, and where are we headed?

Despite the heavy subject matter, all these books were fun to read, and most of them are pretty short. Even the longest (Leonardo) goes quickly. If you’re looking for something to read over the next few months, you can’t go wrong with:

Leonardo da Vinci, by Walter Isaacson. I think Leonardo was one of the most fascinating people ever. Although today he’s best known as a painter, Leonardo had an absurdly wide range of interests, from human anatomy to the theater. Isaacson does the best job I’ve seen of pulling together the different strands of Leonardo’s life and explaining what made him so exceptional. A worthy follow-up to Isaacson’s great biographies of Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs.

Everything Happens for a Reason and Other Lies I’ve Loved, by Kate Bowler. When Bowler, a professor at Duke Divinity School, is diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer, she sets out to understand why it happened. Is it a test of her character? The result is a heartbreaking, surprisingly funny memoir about faith and coming to grips with your own mortality.

Lincoln in the Bardo, by George Saunders. I thought I knew everything I needed to know about Abraham Lincoln, but this novel made me rethink parts of his life. It blends historical facts from the Civil War with fantastical elements—it’s basically a long conversation among 166 ghosts, including Lincoln’s deceased son. I got new insight into the way Lincoln must have been crushed by the weight of both grief and responsibility. This is one of those fascinating, ambiguous books you’ll want to discuss with a friend when you’re done.

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything, by David Christian. David created my favorite course of all time, Big History. It tells the story of the universe from the big bang to today’s complex societies, weaving together insights and evidence from various disciplines into a single narrative. If you haven’t taken Big History yet, Origin Story is a great introduction. If you have, it’s a great refresher. Either way, the book will leave you with a greater appreciation of humanity’s place in the universe.

Factfulness, by Hans Rosling, with Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund. I’ve been recommending this book since the day it came out. Hans, the brilliant global-health lecturer who died last year, gives you a breakthrough way of understanding basic truths about the world—how life is getting better, and where the world still needs to improve. And he weaves in unforgettable anecdotes from his life. It’s a fitting final word from a brilliant man, and one of the best books I’ve ever read.

Turtles and jazz chickens

5 amazing books I read this year

Great reads for the holiday season.

Reading is my favorite way to indulge my curiosity. Although I’m lucky that I get to meet with a lot of interesting people and visit fascinating places through my work, I still think books are the best way to explore new topics that interest you.

This year I picked up books on a bunch of diverse subjects. I really enjoyed Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS by Joby Warrick. I recommend it to anyone who wants a compelling history lesson on how ISIS managed to seize power in Iraq.

On the other end of the spectrum, I loved John Green’s new novel, Turtles All the Way Down, which tells the story of a young woman who tracks down a missing billionaire. It deals with serious themes like mental illness, but John’s stories are always entertaining and full of great literary references.

Another good book I read recently is The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein. I’ve been trying to learn more about the forces preventing economic mobility in the U.S., and it helped me understand the role federal policies have played in creating racial segregation in American cities.

I’ve written longer reviews about some of the best books I read this year. They include a memoir by one of my favorite comedians, a heartbreaking tale of poverty in America, a deep dive into the history of energy, and not one but two stories about the Vietnam War. If you’re looking to curl up by the fireplace with a great read this holiday season, you can’t go wrong with one of these.

The Best We Could Do,by Thi Bui. This gorgeous graphic novel is a deeply personal memoir that explores what it means to be a parent and a refugee. The author’s family fled Vietnam in 1978. After giving birth to her own child, she decides to learn more about her parents’ experiences growing up in a country torn apart by foreign occupiers.

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, by Matthew Desmond. If you want a good understanding of how the issues that cause poverty are intertwined, you should read this book about the eviction crisis in Milwaukee. Desmond has written a brilliant portrait of Americans living in poverty. He gave me a better sense of what it is like to be poor in this country than anything else I have read.

Believe Me: A Memoir of Love, Death, and Jazz Chickens, by Eddie Izzard. Izzard’s personal story is fascinating: he survived a difficult childhood and worked relentlessly to overcome his lack of natural talent and become an international star. If you’re a huge fan of him like I am, you’ll love this book. His written voice is very similar to his stage voice, and I found myself laughing out loud several times while reading it.

The Sympathizer,by Viet Thanh Nguyen. Most of the books I’ve read and movies I’ve seen about the Vietnam War focused on the American perspective. Nguyen’s award-winning novel offers much-needed insight into what it was like to be Vietnamese and caught between both sides. Despite how dark it is, The Sympathizer is a gripping story about a double agent and the trouble he gets himself into.

Energy and Civilization: A History, by Vaclav Smil. Smil is one of my favorite authors, and this is his masterpiece. He lays out how our need for energy has shaped human history—from the era of donkey-powered mills to today’s quest for renewable energy. It’s not the easiest book to read, but at the end you’ll feel smarter and better informed about how energy innovation alters the course of civilizations.

Outside in

5 good summer reads

Books I hope you’ll enjoy as the days get longer.

Summer is a great time to escape: to the beach, to the mountains, or to the world of a great book. This year, I found myself drawn even more than usual to books that took me outside (and I don’t mean the great outdoors). The books on this year’s summer reading list pushed me out of my own experiences, and I learned some things that shed new light on how our experiences shape us and where humanity might be headed.

Some of these books helped me better understand what it’s like to grow up outside the mainstream: as a child of mixed race in apartheid South Africa, as a young man trying to escape his impoverished life in rural Appalachia, or as the son of a peanut farmer in Plains, Georgia. I hope you’ll find that others make you think deeper about what it means to truly connect with other people and to have purpose in your life. And all of them will transport you somewhere else—whether you’re sitting on a beach towel or on your own couch.

Born a Crime, by Trevor Noah. As a longtime fan of The Daily Show, I loved reading this memoir about how its host honed his outsider approach to comedy over a lifetime of never quite fitting in. Born to a black South African mother and a white Swiss father in apartheid South Africa, he entered the world as a biracial child in a country where mixed race relationships were forbidden. Much of Noah’s story of growing up in South Africa is tragic. Yet, as anyone who watches his nightly monologues knows, his moving stories will often leave you laughing.

The Heart, by Maylis de Kerangal. While you’ll find this book in the fiction section at your local bookstore, what de Kerangal has done here in this exploration of grief is closer to poetry than anything else. At its most basic level, she tells the story of a heart transplant: a young man is killed in an accident, and his parents decide to donate his heart. But the plot is secondary to the strength of its words and characters. The book uses beautiful language to connect you deeply with people who may be in the story for only a few minutes. For example, de Kerangal goes on for pages about the girlfriend of the surgeon who does the transplant even though you never meet that character. I’m glad Melinda recommended this book to me, and I recently passed it along to a friend who, like me, sticks mostly with nonfiction.

Hillbilly Elegy, by J.D. Vance. The disadvantaged world of poor white Appalachia described in this terrific, heartbreaking book is one that I know only vicariously. Vance was raised largely by his loving but volatile grandparents, who stepped in after his father abandoned him and his mother showed little interest in parenting her son. Against all odds, he survived his chaotic, impoverished childhood only to land at Yale Law School. While the book offers insights into some of the complex cultural and family issues behind poverty, the real magic lies in the story itself and Vance’s bravery in telling it.

Homo Deus, by Yuval Noah Harari. I recommended Harari’s previous book Sapiens in last summer’s reading list, and this provocative follow-up is just as challenging, readable, and thought-provoking. Homo Deus argues that the principles that have organized society will undergo a huge shift in the 21st century, with major consequences for life as we know it. So far, the things that have shaped society—what we measure ourselves by—have been either religious rules about how to live a good life, or more earthly goals like getting rid of sickness, hunger, and war. What would the world be like if we actually achieved those things? I don’t agree with everything Harari has to say, but he has written a smart look at what may be ahead for humanity.

A Full Life, by Jimmy Carter. Even though the former President has already written more than two dozen books, he somehow managed to save some great anecdotes for this quick, condensed tour of his fascinating life. I loved reading about Carter’s improbable rise to the world’s highest office. The book will help you understand how growing up in rural Georgia in a house without running water, electricity, or insulation shaped—for better and for worse—his time in the White House. Although most of the stories come from previous decades, A Full Life feels timely in an era when the public’s confidence in national political figures and institutions is low.

Great Reads

My favorite books of 2016

From tennis to tennis shoes and genomics to great leadership, these books delivered unexpected insights and pleasures.

Never before have I felt so empowered to learn as I do today. When I was young, there were few options to learn on my own. My parents had a set of World Book Encyclopedias, which I read through in alphabetical order. But there were no online courses, video lectures, or podcasts to introduce me to new ideas and thinkers as we have today.

Still, reading books is my favorite way to learn about a new topic. I’ve been reading about a book a week on average since I was a kid. Even when my schedule is out of control, I carve out a lot of time for reading.

If you’re looking for a book to enjoy over the holidays, here are some of my favorites from this year. They cover an eclectic mix of topics—from tennis to tennis shoes, genomics to great leadership. They’re all very well written, and they all dropped me down a rabbit hole of unexpected insights and pleasures.

String Theory, by David Foster Wallace. This book has nothing to do with physics, but its title will make you look super smart if you’re reading it on a train or plane. String Theory is a collection of five of Wallace’s best essays on tennis, a sport I gave up in my Microsoft days and am once again pursuing with a passion. You don’t have to play or even watch tennis to love this book. The late author wielded a pen as skillfully as Roger Federer wields a tennis racket. Here, as in his other brilliant works, Wallace found mind-blowing ways of bending language like a metal spoon.

Shoe Dog, by Phil Knight. This memoir, by the co-founder of Nike, is a refreshingly honest reminder of what the path to business success really looks like: messy, precarious, and riddled with mistakes. I’ve met Knight a few times over the years. He’s super nice, but he’s also quiet and difficult to get to know. Here Knight opens up in a way few CEOs are willing to do. I don’t think Knight sets out to teach the reader anything. Instead, he accomplishes something better. He tells his story as honestly as he can. It’s an amazing tale.

The Gene, by Siddhartha Mukherjee. Doctors are deemed a “triple threat” when they take care of patients, teach medical students, and conduct research. Mukherjee, who does all of these things at Columbia University, is a “quadruple threat,” because he’s also a Pulitzer Prize– winning author. In his latest book, Mukherjee guides us through the past, present, and future of genome science, with a special focus on huge ethical questions that the latest and greatest genome technologies provoke. Mukherjee wrote this book for a lay audience, because he knows that the new genome technologies are at the cusp of affecting us all in profound ways.

The Myth of the Strong Leader, by Archie Brown. This year’s fierce election battle prompted me to pick up this 2014 book, by an Oxford University scholar who has studied political leadership—good, bad, and ugly—for more than 50 years. Brown shows that the leaders who make the biggest contributions to history and humanity generally are not the ones we perceive to be “strong leaders.” Instead, they tend to be the ones who collaborate, delegate, and negotiate—and recognize that no one person can or should have all the answers. Brown could not have predicted how resonant his book would become in 2016.

Honorable mention: The Grid, by Gretchen Bakke. This book, about our aging electrical grid, fits in one of my favorite genres: “Books About Mundane Stuff That Are Actually Fascinating.” Part of the reason I find this topic fascinating is because my first job, in high school, was writing software for the entity that controls the power grid in the Northwest. But even if you have never given a moment’s thought to how electricity reaches your outlets, I think this book would convince you that the electrical grid is one of the greatest engineering wonders of the modern world. I think you would also come to see why modernizing the grid is so complex and so critical for building our clean-energy future.

Great Reads

5 books to read this summer

Each one kept me up reading long past when I should have gone to sleep.

Here in Seattle, summer is a gift you earn by gutting out nine months of rain and gloom. The skies are clear, there’s hardly any humidity, and the nights are cool. Best of all, you sometimes get the chance to sit outside reading a great book.

This summer, my recommended reading list has a good dose of books with science and math at their core. But there’s no science or math to my selection process. The following five books are simply ones that I loved, made me think in new ways, and kept me up reading long past when I should have gone to sleep. As a result, this is an eclectic list—from an 800-page science fiction novel by a local legend to a 200-page nonfiction book on how Japan can get its economic mojo back. I hope you find at least one book here that inspires you to go off the beaten path when you get some time to yourself this summer.

Seveneves, by Neal Stephenson. I hadn’t read any science fiction for a decade when a friend recommended this novel. I’m glad she did. The plot gets going in the first sentence, when the moon blows up. People figure out that in two years a cataclysmic meteor shower will wipe out all life on Earth, so the world unites on a plan to keep humanity going by launching as many spacecraft as possible into orbit. You might lose patience with all the information you’ll get about space flight—Stephenson, who lives in Seattle, has clearly done his research—but I loved the technical details. Seveneves inspired me to rekindle my sci-fi habit.

How Not to be Wrong, by Jordan Ellenberg. Ellenberg, a mathematician and writer, explains how math plays into our daily lives without our even knowing it. Each chapter starts with a subject that seems fairly straightforward—electoral politics, say, or the Massachusetts lottery—and then uses it as a jumping-off point to talk about the math involved. In some places the math gets quite complicated, but he always wraps things up by making sure you’re still with him. The book’s larger point is that, as Ellenberg writes, “to do mathematics is to be, at once, touched by fire and bound by reason”—and that there are ways in which we’re all doing math, all the time.