Co-op mode

This novel about video games felt personal to me

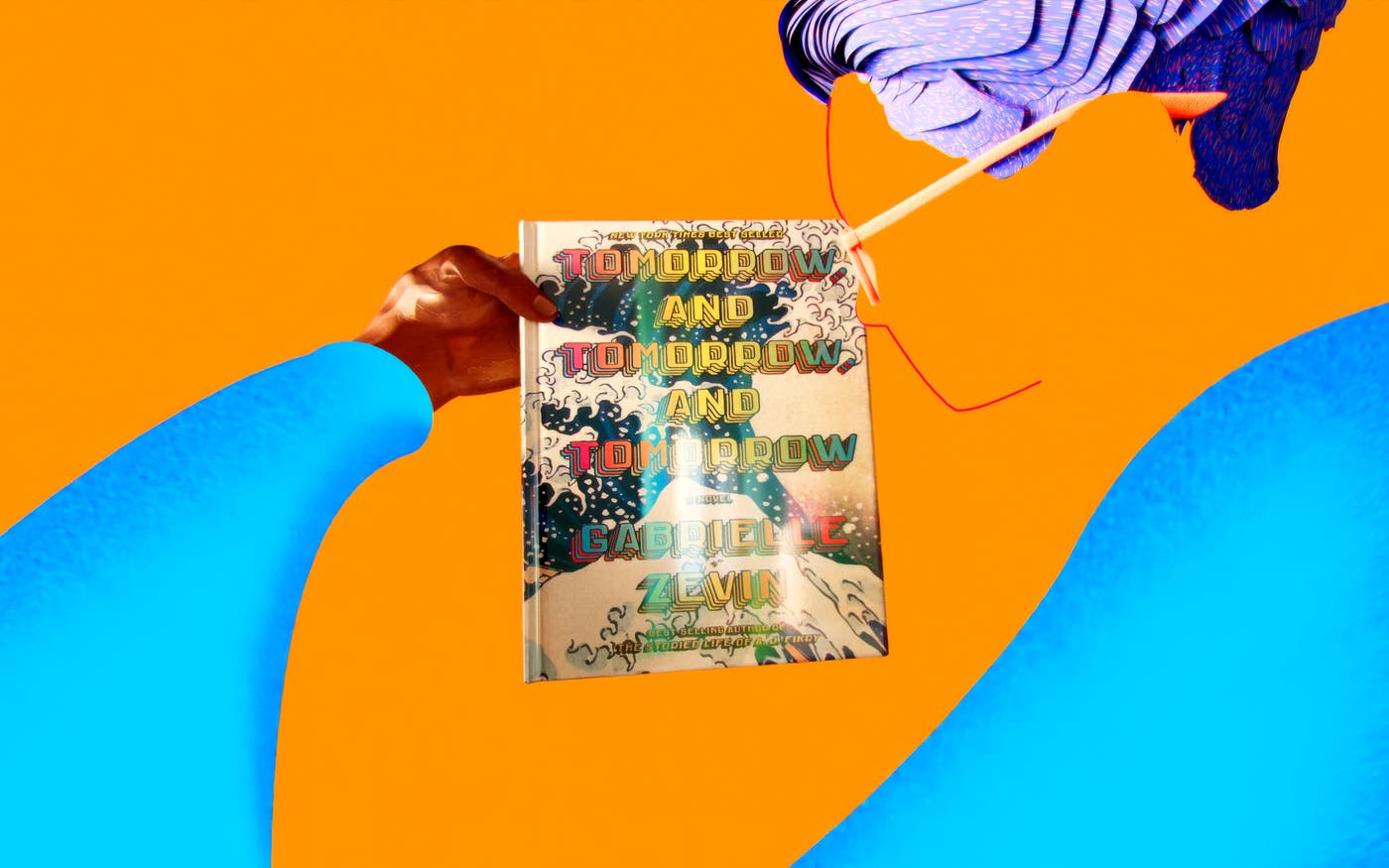

I never thought I’d relate to a book about gaming, but I loved Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.

Am I a gamer? For a long time, I would have said no because I don’t spend hundreds of hours going deep on one game.

But when I was younger, I loved arcade games and got very good at Tetris. And in recent years, I have started playing a lot of online bridge and games like Spelling Bee and a bunch of the Wordle variants. The definition of a gamer is becoming a lot broader and more inclusive, and it might be fair to start calling me one.

Either way, I don’t think you need to be a hardcore gamer to enjoy Gabrielle Zevin’s terrific novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. It tells the story of Sam and Sadie, two friends who bond over Super Mario Bros. as kids and grow up to make video games together. Tomorrow was one of the biggest books of last year, and it’s easy to see why. Zevin is a great writer who makes you care deeply about her characters.

Although there are plenty of video games mentioned in the book—Oregon Trail is a recurring theme—I’d describe it more as a story about partnership and collaboration. When Sam and Sadie are in college, they create a game called Ichigo that turns out to be a huge hit. Their company, Unfair Games, becomes successful, but the two start to butt heads. Sadie is upset that Sam got most of the credit for Ichigo. Sam is frustrated that Sadie cares more about creating art than about making their company viable.

Zevin is such a good writer that she makes you sympathize equally with both of them. Female game developers often struggle to receive recognition, so Sadie’s position is understandable. But she also comes from a well-off family unlike Sam, who grew up poor and sees Unfair Games as his gateway to achieving financial stability for the first time. Most of the book is about how a creative partnership can be equal parts remarkable and complicated.

I couldn’t help but be reminded of my relationship with Paul Allen while I was reading it. Sadie believes that “true collaborators in this life are rare.” I agree, and I was lucky to have one in Paul.

An early chapter describing how Sam and Sadie worked until sunrise in a dingy apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, could have just as easily been about Paul and me coming up with the idea for Microsoft. Like Sam and Sadie, we worked together every day for years. Paul’s vision and contributions to the company were absolutely critical to its success, and then he chose to move on. We had a great relationship, but not without some of the complexities that success brings.

Zevin really captures what it feels like to start a company that takes off. It’s thrilling to know your vision is now real, but success brings a lot of new questions. Once you make money, do you still have something to prove? How does your relationship with your partner change once a lot more people get involved? How do you make the next idea as good as the last?

You can’t help but wonder whether you would’ve been as successful if you started up at a different time. Sadie says, “If we’d been born a little bit earlier, we wouldn’t have been able to make our games so easily. Access to computers would have been harder… And if we’d been born a little bit later, there would have been even greater access to the internet and certain tools, but honestly, the games got so much more complicated; the industry got so professional. We couldn’t have done as much as we did on our own.” I know what she means: Paul and I were very lucky in terms of our timing with Microsoft. We got in when chips were just starting to become powerful but before other people had created established companies.

Another part of the book that felt familiar to me was Sam and Sadie’s dynamic with Marx, a college friend who is an equal partner in their work. Marx isn’t a game designer like Sam and Sadie, but Ichigo and Unfair Games wouldn’t have happened without his production and business savvy. He’s also a charming, funny character who you can’t help but root for throughout the book.

If Paul and I were Sam and Sadie, Steve Ballmer was our Marx. He didn’t write code, but the success of Microsoft was highly dependent on him. Like Marx, Steve made sure we hired the right people and had the tools we needed for the company to take off. The comparison isn’t perfect: We always appreciated Steve’s value, but in the book, Sam comes to resent Marx and downplays his contributions. (And of course Steve became Microsoft’s CEO, a position that Marx never reaches at Unfair Games.) But Zevin understands that dreamers alone can’t turn big ideas into reality—you need doers, too.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow resonated with me for personal reasons, but I think Zevin’s exploration of partnership and collaboration is worth reading no matter who you are. Even if you’re skeptical about reading a book about video games, the subject is a terrific metaphor for human connection. As Zevin writes, “To allow yourself to play with another person is no small risk. It means allowing yourself to be open, to be exposed, to be hurt. To play requires trust and love.”