Laugh-Out-Loud Sad

A funny, brutally honest memoir

Allie Brosh’s memoir looks openly at depression. It’s also very funny.

Some of the books I’ve recommended as summer reads really aren’t. They’re long nonfiction books that might look a little out of place beside the pool or on the beach.

But Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things that Happened , by Allie Brosh, is an honest-to-goodness summer read. You will rip through it in three hours, tops. But you’ll wish it went on longer, because it’s funny and smart as hell. I must have interrupted Melinda a dozen times to read to her passages that made me laugh out loud.

The book consists of brief vignettes and comic (in both senses of the word) drawings about Brosh’s young life (she’s in her late 20s). It’s based on her wildly popular website.

Brosh has quietly earned a big following even though, as her official bio puts it, she “lives as a recluse in her bedroom in Bend, Oregon.” The adventures she recounts are mostly inside her head, where we hear and see the kind of inner thoughts most of us are too timid to let out in public. Despite her book’s title, Brosh’s stories feel incredibly—and sometimes brutally—real.

I don’t mean to suggest that giving an outlet to our often-despicable me is a novel form of humor, but she is really good at it. Her timing and tone are consistently spot on. And so is her artwork. I’m amazed at how expressive and effective her intentionally crude drawings are.

Some of Brosh’s stories are funny without being particularly meaningful, such as her tales about her two dogs and their humorously illogical inner thoughts. Here’s a typical snippet: “To the simple dog, throwing up was like some magical power that she never knew she possessed—the ability to create infinite food. I was less excited about the discovery because it turned my dog into a horrible, vomit-making perpetual-motion machine.”

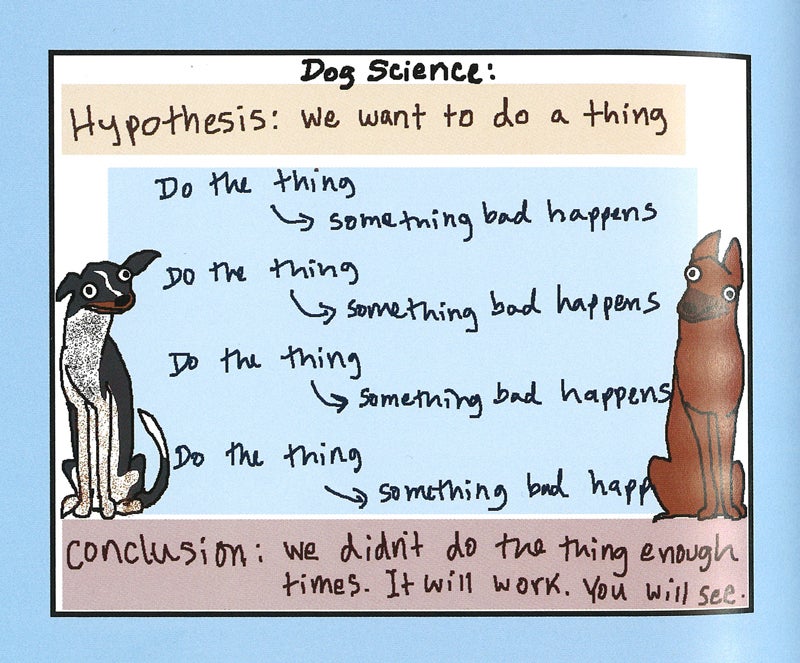

And here’s a typical illustration:

But her best stuff is the deep stuff, especially the chapters about her battles with severe depression. There is a lot of self-revelation here but no self-pity. She brings the same wit to this subject as she does to her stories about her dogs—even if it makes the reader more likely to tear up than crack up.

Here’s a typical snippet that follows a riff about feeling suicidal and not quite knowing how to let loved ones know about these feelings:

I suspect that anyone who has experienced depression would get a lot out of reading this book. The mental illness she describes is profoundly isolating: “When you have to spend every social interaction consciously manipulating your face into shapes that are only approximately the right ones, alienating people is inevitable.” It must be empowering for those who have struggled with depression to read this book, see themselves, and know they’re far from alone.

It might be even more valuable for those who have a friend, colleague, or family member who has experienced depression. Hyperbole and a Half gave me a new appreciation for what a depressed person is feeling and notnot feeling, and what’s helpful and helpful. Here’s a good example: “People want to help. So they try harder to make you feel hopeful…. You explain it again, hoping they’ll try a less hope-centric approach, but re-explaining your total inability to experience joy inevitably sounds kind of negative, like maybe you WANT to be depressed. So the positivity starts coming out in a spray—a giant, desperate happiness sprinkler pointed directly at your face.”

I get why Brosh has become so popular. While she self-deprecatingly depicts herself in words and art as an odd outsider, we can all relate to her struggles. Rather than laughing at her, you laugh with her. It is no hyperbole to say I love her approach—looking, listening, and describing with the observational skills of a scientist, the creativity of an artist, and the wit of a comedian.