Curing the World

Lessons from eradication

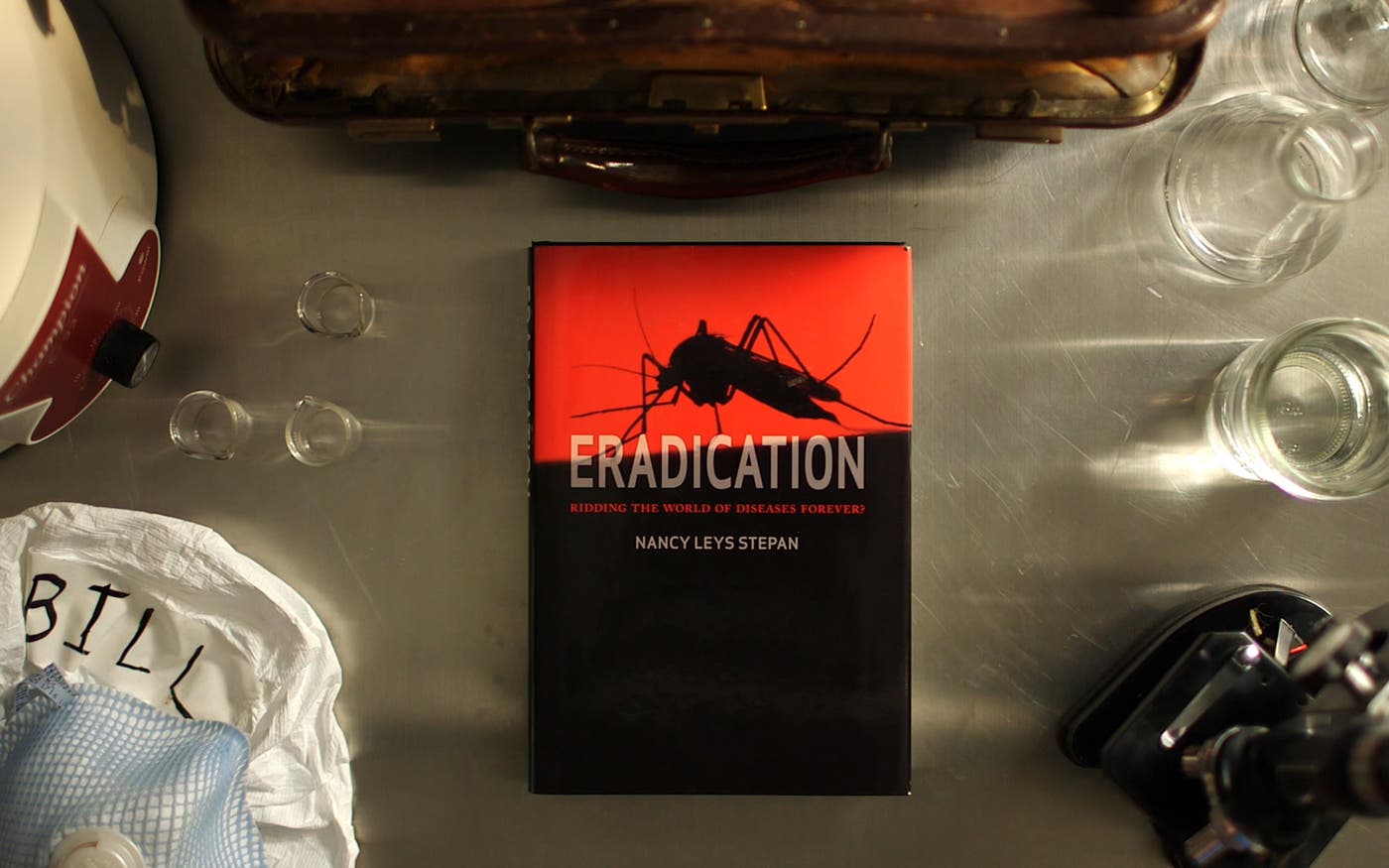

Nancy Leys Stepan has written a useful history of efforts to eliminate diseases.

I don’t remember the first time I heard of smallpox, but when I was a kid in Seattle in the 1960s it wasn’t exactly top of mind for my friends and me. I’m sure I heard about it when the World Health Organization announced in 1980 that smallpox had been eradicated, but I still didn’t pay much attention. After all, smallpox had been eradicated in the United States for almost a century; it’s hard to get too worked up about a disease that nobody you know has ever gotten. It wasn’t until later, when our foundation joined global eradication efforts, that I really started thinking about what it takes to wipe a disease from the face of the earth. Most people think it’s incredibly difficult. It turns out, it’s much harder than that.

That’s why I enjoyed Nancy Leys Stepan’s book Eradication: Ridding the World of Diseases Forever?. It gives you a good sense of how involved the effort to eradicate a disease can get , how many different kinds of approaches have been tried without success, and how much we’ve learned from our failures.

To illustrate the history of eradication, she focuses on the career of Fred Soper, who led efforts to eradicate yellow fever, typhus, and malaria, first at the Rockefeller Foundation and then, from 1947 to 1959, as director of the Pan-American Health Organization.

I’m a little more positive on Soper than Stepan is, but the view she gives of him is very balanced. He got a lot done, but he did it by being extremely demanding, both in his eradication methods and in his dealings with people, and that made him both very effective in some ways and very difficult to deal with. He reportedly tried to strangle somebody who disagreed with him in a meeting. Despite his faults, though, without Soper, I don’t know that we would have eradicated smallpox or that we would be on the verge of eradicating polio.

Soper’s biggest mistake—and on this I agree with Stepan—was believing that scientists had already learned everything there was to learn about mosquitoes and malaria. Because of that he spent a lot of time and money—and made life harder for a lot of people—trying to eradicate a disease that actually was not understood well enough. Scientists didn’t have enough of the right data. Soper didn’t have a deep enough understanding of human behavior and international politics. And most of all, he didn’t doubt himself enough. I think we’re approaching all these issues in better ways today, and I remain optimistic about the world’s strategy to get rid of malaria for good.

I feel similarly optimistic about the effort to eradicate polio. Although it has taken longer and cost more than we thought it would, there are now only two countries that have never been polio-free—Afghanistan and Pakistan—and we're on the verge of eradicating it entirely. Once that happens, we’ll be able to use the infrastructures we’ve set up for taking on other diseases.

I do disagree with some of Stepan’s arguments. For example she faults eradication programs for not strengthening health infrastructures—she writes that they can come “at the expense of a broader approach to ill health.” In theory, they can—but more and more, they don’t. The systems being put in place to deal with polio are actually strengthening health systems more broadly. Part of the reason Nigeria was able to contain Ebola during the recent outbreak was that polio workers there were able to step in to help with the response. Without them, the country's 180 million citizens would have been at far greater risk; in fact, in countries without the polio-eradication infrastructure, the outbreak was much worse.

Finally, a word of warning: Eradication is written in a very academic style, and it may be a challenge for non-experts to get to Stepan’s valuable arguments. It’s worth the effort, though, because you come away from it with a clearer sense of what the world has learned about getting rid of diseases and how we can use that to guide the effort to save even more lives.