Fast Fears, Slow Truths

Where do vaccine fears come from?

A new mother writes about the world of vaccines.

In his 2013 New Yorker article “Slow Ideas,” the Harvard surgeon Atul Gawande offered a compelling way to understand why some good ideas spread slowly (if at all) while others spread like wildfire.

Gawande’s story begins in 1846, when Dr. Henry Jacob Bigelow published the first account of the use of an inhaled anesthetic to produce “insensibility” during surgery. Within months, surgeons all around the world took up the idea and began using their own ether-based concoctions. When you consider that there were no phones or airplanes to carry the news, it’s amazing how fast the concept of anesthesia spread.

Gawande’s second case study begins two decades later, when the surgeon Joseph Lister reported in The Lancet that patients had much higher survival rates when he used carbolic acid to clean his hands and instruments prior to putting patients under the knife. However, Lister’s simple and effective antiseptic techniques did not go viral. It took a generation for these smart ideas to take hold.

What accounts for the difference in speed? In the case of anesthesia, the benefits of not having patients screaming and thrashing around during surgery were immediate—and they easily trumped the objections and fears that arose from clergymen and others. The same was not true of Lister’s antiseptic method. Because infection was largely an invisible problem and the symptoms appeared after patients left their surgeon’s care, the benefits of antisepsis were not as obvious. Meanwhile, there was a clear cost to doctors: the carbolic acid burned their hands.

I have found it useful to apply this thinking to the field of immunization, a field that is once again making big headlines, this time as a result of the California measles outbreak and the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. Vaccines are at once the source of both super-fast ideas and super-slow ones. Tiny injections of misinformation about vaccines often race around the globe in minutes while, in the words of Mark Twain, “the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

As with Lister’s antiseptic method, the benefits of getting the MMR or Hib vaccine are invisible while you’re sitting in the doctor’s office. For some people, invisible benefits that might materialize in the future are just not enough to get them over the clear and present fears common to all parents that something we’re exposing our children to could result in harm. As Melinda noted recently, most Americans “have forgotten what measles deaths look like.” Because of that luxury, a thin needle and glass vial can look scary.

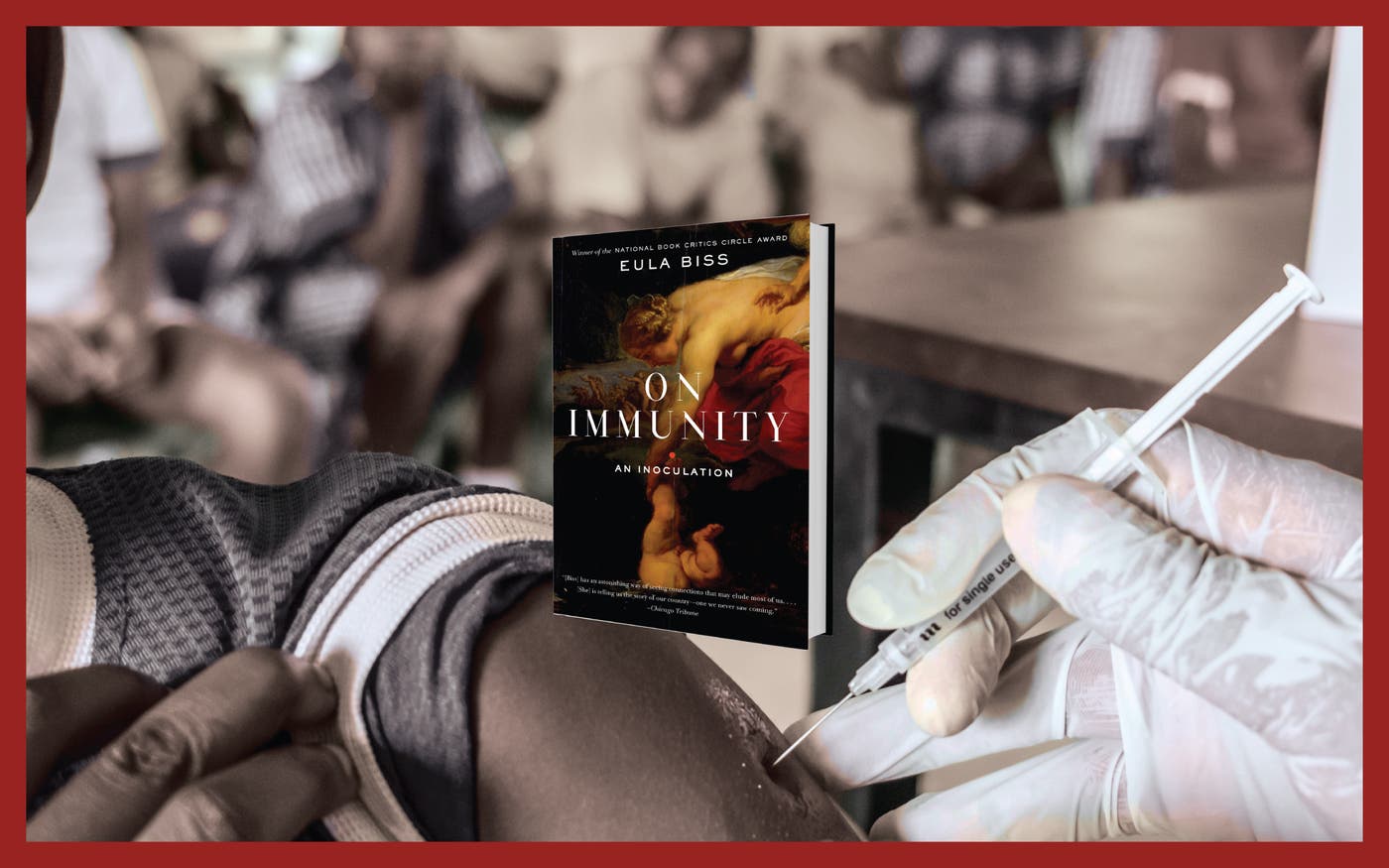

I have new perspective on the power of those fears after reading On Immunity, by the Northwestern University lecturer and essayist Eula Biss. When I stumbled across the book on the Internet, I thought it might be a worthwhile read. I had no idea what a pleasure reading it would be.

I also had no idea how informative it would be, even for someone like me who has been supporting and learning about vaccine research for many years. A lot of people who talk about vaccines—no matter what side they’re on—don’t invest the time to understand the topic. But Biss really did her homework. Like many of us, she concludes that vaccines are safe, effective, and almost miraculous tools for protecting our children against needless suffering.

She is not out to demonize anyone who holds opposing views. She’s a new mother who empathizes with other parents trying to make the best decisions for their children.

What makes this book so good and unusual is how effortlessly Biss moves around different topics. Her father is an oncologist and her mother a poet, which probably helps to explain how Biss so easily navigates the worlds of science and literature. And she’s just as good when she draws on insights from psychology, sociology, women’s studies, history, and philosophy.

One of the virtues of crossing so many boundaries is that it helps expand the way we view these issues. On the cover of the March National Geographic, the magazine’s editors depict vaccine refusal as an iconic example of a “war on science.” But Biss argues persuasively that distrust of science is just one factor. She explores many different things that have triggered people’s fears: pharmaceutical companies, big government, elites, toxic polluters, the medical establishment, male authority, and even vampires.

In an era when trust in just about every institution is waning, those of us who are working to increase vaccination rates face a daunting convergence of fears. What can we do to address them? First, we cannot just dismiss them as ignorant or “anti-science.” Second, I believe we have to accept that good news about vaccines is inherently slow and fears are inherently fast. The words of national experts and eloquent writers like Biss can make a difference, but when it comes to slow ideas, people are most influenced by those they know and trust—friends, family members, doctors, and teachers. As Gawande writes, “Going ‘low touch,’ without sandals on the ground,” just doesn’t work. “People talking to people is still how the world’s standards change.”