Getting better

An Auschwitz survivor’s guide to healing

Eger’s life story gives her fascinating insight into how people move on after trauma.

How do you move on after trauma?

That’s a question many of us will unfortunately have to grapple with at some point in our lives. It’s certainly relevant right now. The good news is that there is no shortage of smart, thoughtful people out there offering advice on the subject. I recently read a book by Dr. Edith Eva Eger that I think is particularly useful.

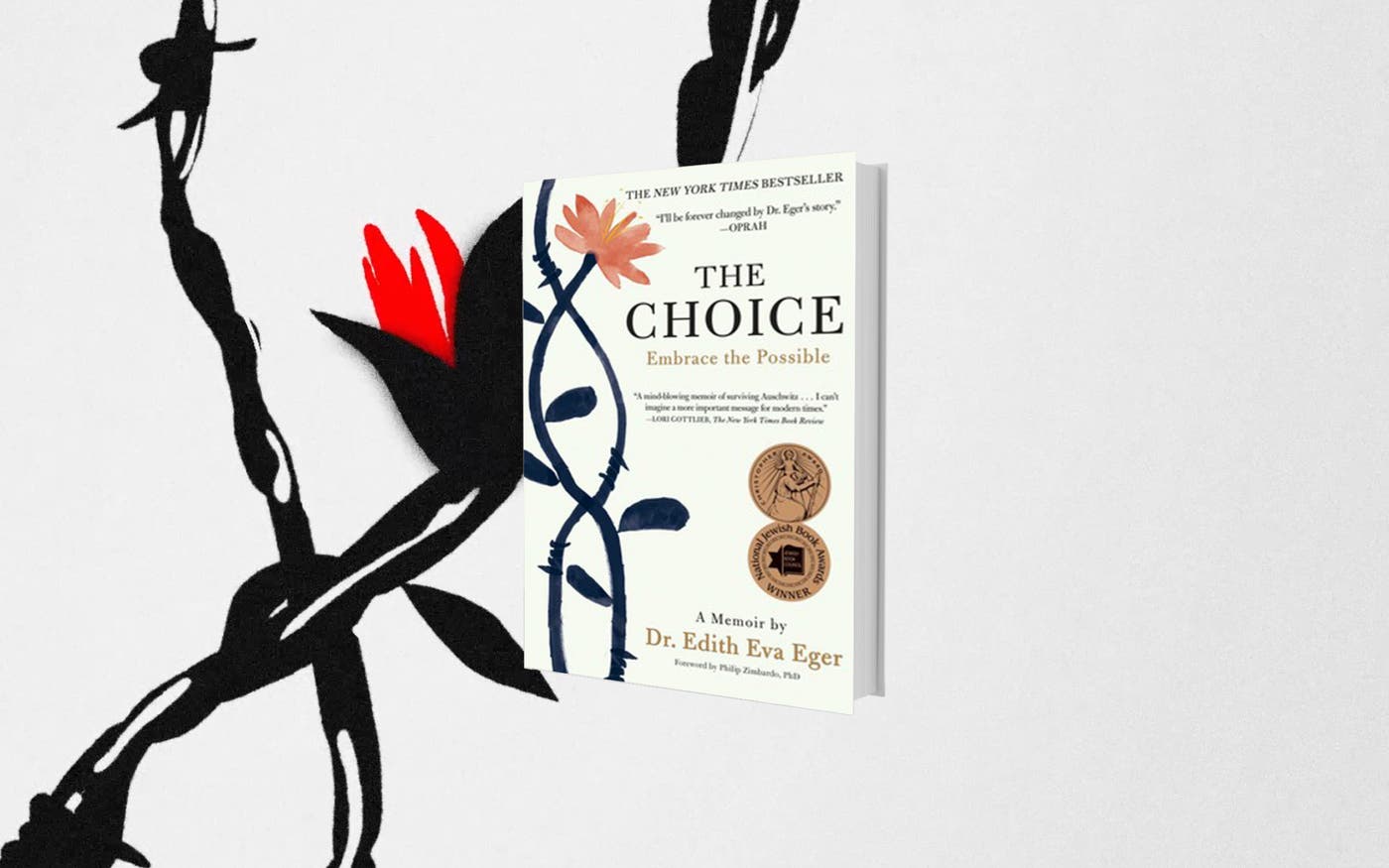

The Choice is partly a memoir and partly a guide to processing trauma. Melinda recommended that I read it, and I’m glad she did. What makes the book exceptional is Edith’s life story: she’s an Auschwitz survivor and a professional therapist. That combination gives her fascinating insight into how people heal.

Edith was just a teenager when her family was taken from their home in Hungary and sent to the death camp at Auschwitz. She was separated from her parents, whom she never saw again. Edith and her sister Magda managed to stay together, though, and they spent the next year helping each other survive unbelievable horrors.

Even after the sisters are liberated, Edith’s trauma doesn’t end. I don’t want to give away specifics, but the book offers a look into how chaotic the post-war period was in Europe. Her story is a reminder of how people’s worst instincts can come out when civil order is completely broken down. Edith remained a victim long after her rescue, even as she’s supposed to be healing from the physical trauma she sustained at Auschwitz.

Eventually, though, Edith met the man who became her husband and moved to the United States. After a rough couple of years, she started a family and learned enough English to begin studying psychology at the University of Texas, El Paso. Her past continued to haunt her, though—she often found herself paralyzed by memories of the concentration camp.

Everything changed when a fellow student gave her a copy of Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl was a prisoner at Auschwitz at the same time as Edith, and his writing becomes the inspiration for her philosophy as a therapist. The lesson she says she took from it is that “each moment is a choice. No matter how frustrating or boring or constraining or painful or oppressive our experience, we can always choose how we respond.” (I read Man’s Search for Meaning many years ago, and I completely understand why it made such an impact on Edith.)

Edith begins processing her past--she even returns to visit Auschwitz as part of the healing process. All the while, she builds a career as a successful therapist who specializes in trauma. This is when the book starts to become more of a guide. She talks a lot about her patients, some of whom suffer from PTSD and have really tragic stories. But not all of her patients have experienced huge traumas.

I think it’s important to point out that her approach applies to everyday disappointments, too. In one memorable story at the beginning of the book, Edith talks about a patient who cried over the fact that her new car was the wrong shade of yellow. Your first reaction as a reader is to see the woman as petty. How can she be upset over a such a silly thing when there is real suffering in the world?

Edith doesn’t see it that way, though. She saw that “her tears of disappointment over the car were really tears of disappointment over the bigger things in her life that hadn’t worked out the way she had hoped.” The patient was transferring her emotional isolation to material disappointment. Edith makes a sympathetic and understandable case that there was something missing in that woman’s life that made her latch onto seemingly silly points of validation. She treats the patient’s pain as seriously as she would anyone else’s.

I really like her approach, because it implies that there is a path to getting better no matter what you’re going through. People can struggle and feel worthless without extreme things happening. That pain is still worthy of attention and help.

It’s a good reminder that there is no “hierarchy of suffering,” as Edith calls it. If you’re struggling with something, that struggle is real—even if you think your experience feels trivial compared to the experience of someone who survived Auschwitz or someone whose child is suffering from a terrible disease. I think this is an especially important thing to keep in mind right now while everyone has different experiences with the COVID-19 outbreak.

Although Edith’s early life is what will make you pick up The Choice, her insights as a therapist are what will stick with you long after you finish it. I hope it gives you some comfort in these challenging times.