Read, watch, listen

Great books, courses, and music for the holidays

Some favorites from 2023, including a new playlist.

At the end of the year, it’s always fun to look back on some of the best books I read. For 2023, three came to mind right away, each of them deeply informative and well written. I’ve also included economics courses by a phenomenal lecturer that I watched more than a decade ago but am still recommending to friends and family today. Just for fun, I threw in a playlist of great holiday songs from past and present, and from the U.S. and around the world.

I didn’t have time to write up a full review, but I should mention that I just watched the series All the Light We Cannot See on Netflix. I had read the book, which is amazing, sometimes an adaptation of a book you love can be disappointing. That’s not the case here—the series is just as good. The actor who plays von Rumpel, a Nazi gem hunter and the villain in the story, is especially memorable.

I hope you find something fun here to read, watch, or listen to. And happy holidays!

The Song of the Cell, by Siddhartha Mukherjee. All of us will get sick at some point. All of us will have loved ones who get sick. To understand what’s happening in those moments—and to feel optimistic that things will get better—it helps to know something about cells, the building blocks of life. Mukherjee’s latest book will give you that knowledge. He starts by explaining how life evolved from single-celled organisms, and then he shows how every human illness or consequence of aging comes down to something going wrong with the body’s cells. Mukherjee, who’s both an oncologist and a Pulitzer Prize–winning author, brings all of his skills to bear in this fantastic book.

Not the End of the World, by Hannah Ritchie. Hannah Ritchie used to believe—as many environmental activists do—that she was “living through humanity’s most tragic period.” But when she started looking at the data, she realized that’s not the case. Things are bad, and they’re worse than they were in the distant past, but on virtually every measure, they’re getting better. Ritchie is now lead researcher at Our World in Data, and in Not the End of the World, she uses data to tell a counterintuitive story that contradicts the doomsday scenarios on climate and other environmental topics without glossing over the challenges. Everyone who wants to have an informed conversation about climate change should read this book.

Invention and Innovation, by Vaclav Smil. Are we living in the most innovative era of human history? A lot of people would say so, but Smil argues otherwise. In fact, he writes, the current era shows “unmistakable signs of technical stagnation and slowing advances.” I don’t agree, but that’s not surprising—having read all 44 of his books and spoken with him several times, I know he’s not as optimistic as I am about the prospects of innovation. But even though we don’t see the future the same way, nobody is better than Smil at explaining the past. If you want to know how human ingenuity brought us to this moment in time, I highly recommend Invention and Innovation.

Online economics lectures by Timothy Taylor. I’ve watched a lot of lecture series online, and Taylor is one of my favorite professors. All three of his series on Wondrium are fantastic. The New Global Economy teaches you about the basic economic history of different regions and how markets work. Economics is best suited for people who want to understand the principles of economics in a deep way. Unexpected Economics probably has the broadest audience, because Taylor applies those principles to things in everyday life, including gift-giving, traffic, natural disasters, sports, and more. You can’t go wrong with any of Taylor’s lectures.

A holiday playlist. This one doesn’t need much explanation. I love holiday music and have put together a list of some favorites—classics and modern tunes, from the U.S. and around the world.

Seasons readings

Five books to read this winter

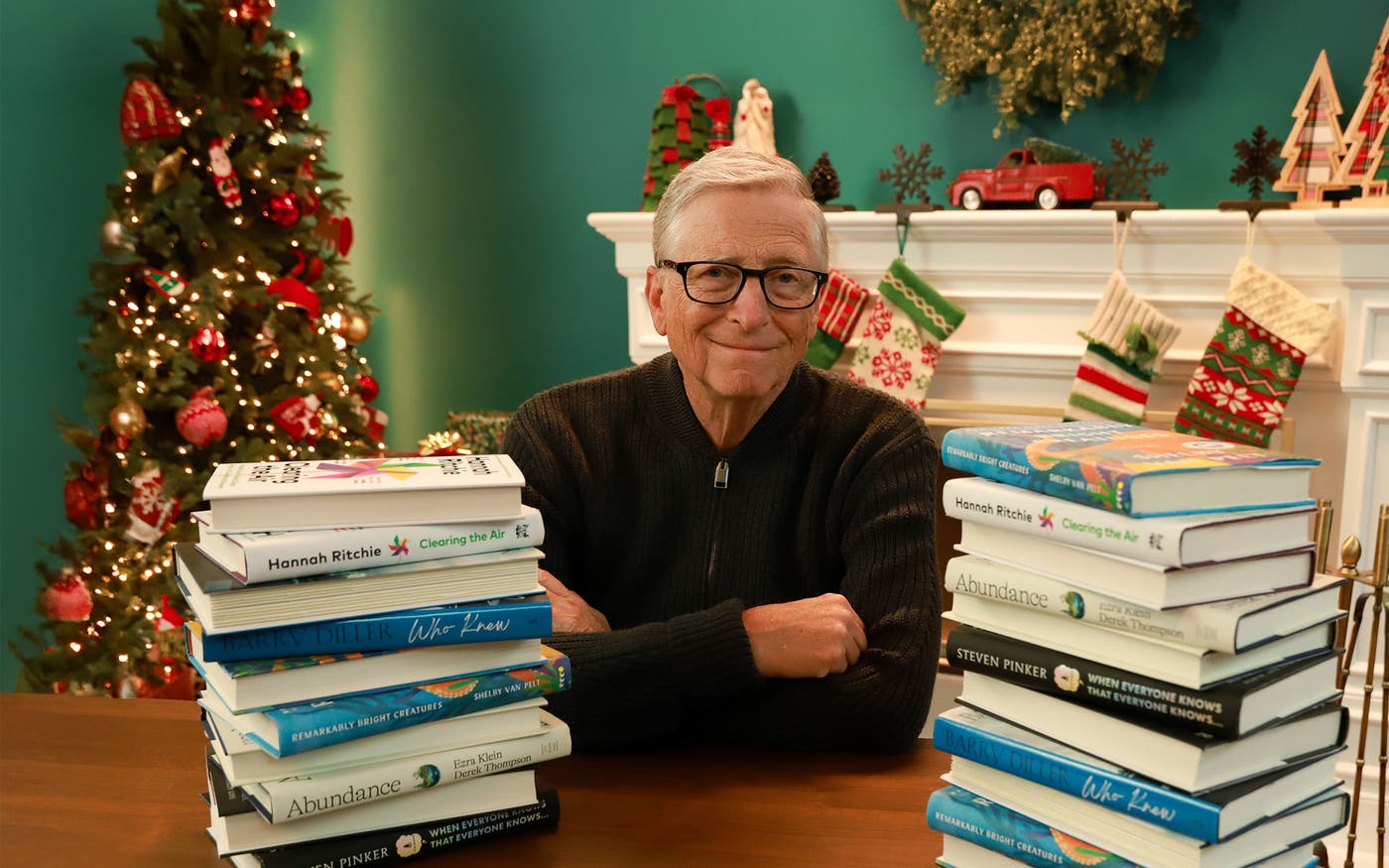

These were some of my favorite books from 2025.

The holidays are almost here. I always love taking advantage of this time of year to catch up on reading, and I know a lot of people feel the same way. There’s something about the quieter days around the holidays that makes it easier to sit down with a good book. So I’m sharing a few recent favorites.

Each of these books pulls back the curtain on how something important really works: how people find purpose later in life, how we should think about climate change, how creative industries evolve, how humans communicate, and how America lost its capacity to build big things—and how to get it back.

I hope you find something here that sparks your curiosity. And I hope your holiday season is filled with happy loved ones, good food, and great conversation.

Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt. I don't read fiction often, but when I do, I want to read about interesting characters who help me see the world in a new way. Remarkably Bright Creatures delivered on that front. I loved this terrific novel about Tova, a 70-year-old woman who works night shifts cleaning an aquarium and finds fulfillment caring for a clever octopus. Tova struggles to find meaning in her life, which is something a lot of people deal with as they get older. Van Pelt's story made me think about the challenge of filling the days after you stop working—and what communities can do to help older people find purpose.

Clearing the Air by Hannah Ritchie. I’ve followed Hannah’s work at Our World in Data for years, and her new book is one of the clearest explanations of the climate challenge I’ve read. She structures it around 50 big questions—like whether it’s too late to act, whether nuclear power is dangerous, and whether renewables really are affordable—and answers each one in concise, accessible language. She’s realistic about the risks but grounded in data that shows real progress: Solar and wind are growing at record speed, electric cars are getting cheaper, and innovation is accelerating across areas like steel, cement, and clean fuels. If you want a hopeful, fact-driven overview of where climate solutions stand, this is a great pick.

Who Knew by Barry Diller. I’ve known Barry for decades, but his memoir still surprised and taught me a lot. He’s one of the most influential figures in modern media. He invented the made-for-TV movie, helped create the TV miniseries, built Paramount into the #1 film studio, launched the Fox broadcast network, and later assembled an internet empire. He’s spent his life betting on ideas before they were obvious, and the industries he’s transformed show how much those bets can pay off.

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows by Steven Pinker. Few people explain the mysteries of human behavior better than Steven Pinker, and his latest book is a must-read for anyone who wants to learn more about how people communicate. When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows shows how “common knowledge” lets people coordinate: When we know what others know, indirect signals become clear. Although the topic itself is pretty complicated, the book is readable and practical, and it made me see everyday social interactions in a new light.

Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. This book is a sharp look at why America seems to struggle to build things and what it will take to fix that. Klein and Thompson argue that progress depends not just on good ideas but on the systems that help ideas spread. Today, these systems often slow things down instead—from housing and infrastructure to clean energy and scientific breakthroughs. I recognized many of the bottlenecks they describe from my own work in global health and climate. Abundance doesn’t pretend to have all the answers, but it asks the right questions about how the U.S. can rebuild our capacity to get big things done.

Under the sea

Growing older with Remarkably Bright Creatures

Shelby Van Pelt’s novel was the perfect way to start my next decade of life.

I turned 70 years old last month. I don’t feel like it, though. I still have a ton of energy, and I have no plans to retire. But somehow, I have officially reached an age my younger self would have called “old.” It’s hard to wrap my head around.

Fortunately, I recently read Remarkably Bright Creatures, a terrific novel that helped me make a bit more sense out of aging. Shelby Van Pelt released her debut novel a couple years ago. It was a huge hit, and I think I might be one of the last people to read it—but I’m glad I waited until now.

Tova, the main character, is also 70, and she feels every single one of those years. Her life hasn’t been easy. Tova’s son is presumed dead after he disappeared when he was a teenager, and her husband died from cancer five years earlier. To pass the time, she works night shifts cleaning the local aquarium, which is where she meets Marcellus, an elderly giant Pacific octopus who is nearing the end of his life.

Marcellus is a fascinating character. Octopuses are some of the smartest animals in the world, and although Marcellus can’t speak, he is super observant. Van Pelt cleverly includes chapters from his perspective, so you get to learn about how he sees the world. He considers Tova a friend after she rescues him after a late-night excursion from his tank goes dangerously wrong. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but Marcellus’s power of observation ends up changing the lives of many of the books’ characters.

Tova gets a much-needed sense of fulfillment from caring for Marcellus and the aquarium. She struggles with purpose throughout the book. Her friends are motivated by their grandchildren, but without her husband and son, Tova feels aimless and alone (even though the reader knows that she has plenty of people in her life who love her—including Ethan, the owner of the local grocery store). Early in the book, she feels so lost that she considers moving away from her hometown and into a senior living community.

Tova’s struggle is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about, because I worry that we might soon see more people feeling like her. As life expectancies go up, many people are living for years and even decades after they stop working. That sounds like a luxury, and it is in a lot of ways—but it is also a lot of time to fill. The decline of third places like churches and libraries makes it harder than ever to find connections that keep the days interesting. Fewer families are having children, which means that fewer older people are becoming grandparents. And while part-time work can help give life meaning, not everyone is physically capable of working.

“Tova has always felt more than a bit of empathy for the sharks, with their never-ending laps around the tank. She understands what it means to never be able to stop moving, lest you find yourself unable to breathe,” Van Pelt writes. Her message is clear: People need a reason to get out of bed in the morning. For many, it’s hard to transition from a lifetime of working to retirement. So, what can we do to help older people find purpose? And how can we prepare for a potential future where technological advances mean all of us have less work to fill our days?

Remarkably Bright Creatures doesn’t try to answer those questions, but Tova’s story really makes you think about how people find meaning in life. Her story is mirrored by Cameron’s, a young man who struggles to find his own purpose and ends up working with Tova at the aquarium. Although their lives couldn’t be more different, I loved seeing how Tova and Cameron help each other find reasons to get out of bed over the course of the story (with help from Marcellus the octopus).

I think anyone who enjoys fiction would enjoy this book, but it’s a must-read for people who grew up in Western Washington like I did. The novel takes place in Sowell Bay, a fictional coastal town that will feel familiar to anyone who has spent time around Puget Sound. Van Pelt captures the specific feeling of weathered charm you get when you visit places like Hood Canal or Anacortes.

I usually read non-fiction books, but Remarkably Bright Creatures gave me exactly what I want whenever I pick up a novel. It transported me to a different world, and it illuminated something new for me—in this case, about relationships and getting older. Reading Tova and Marcellus’s story was the perfect way to start my next decade of life.

Goes without saying

Lessons from a toilet paper shortage

Steven Pinker’s latest book explores the fascinating science behind common knowledge.

Have you ever thought about how weird the question “Can you pass the salt?” is?

It’s an innocuous question that most of us have asked over the dinner table at some point. It’s also a deeply loaded one. When you ask me if I can pass the salt, you are not actually wondering whether I am physically capable of lifting a salt shaker—you want me to hand it to you. But since it feels rude to command someone to pass the salt, the request is couched as a related but different question. And here’s the weirdest part: It works.

Why? Because of something called common knowledge. I know you really mean “Pass me the salt.” And you know I know that. And because both of us know what each other knows, an indirect question is, in reality, super clear.

If that makes your head spin, I get it. Common knowledge is strangely complicated for something so commonplace. Luckily, Steven Pinker explains the topic brilliantly in his latest book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Steven is a cognitive psychologist, and I’m a big fan of his books, which always illuminate something new and fascinating about how humans interact. In this one, he writes about how common knowledge is key to the fabric of social behavior. As Steven explains, it allows “individual minds [to] coordinate their choices for mutual benefit. Many of our harmonies and discords fall out of our struggles to achieve, sustain, or prevent common knowledge.”

The book starts with the famous story of The Emperor’s New Clothes. As soon as a child points out the obvious—the fact that emperor isn’t wearing any clothes—the entire town realizes everyone knows that the emperor is naked and turns on him.

It sounds like a silly folktale until you realize that it reveals a fundamental truth: The social dynamic changes as soon as I know that you know what I know. In this case, people feel more comfortable speaking out publicly once they realize others see the same thing. Common knowledge makes coordination easier, whether it’s something as small as passing the salt or something as big as a protest against an unfair policy.

Common knowledge is a powerful communications tool, but it can also cause chaos. In the book, Steven explains a phenomenon that has baffled me for years: panic-buying toilet paper during an emergency. As far as I know, toilet paper manufacturers have never struggled to meet demand. And yet, every time there’s an emergency—whether it’s a hurricane, a snowstorm, or a pandemic—people rush to the store and clear toilet paper off the shelves.

Steven traces the blame back to Johnny Carson. In 1973, the U.S. was reeling from shortages of gasoline and staples like sugar. Johnny made a joke in his monologue on The Tonight Show about the country running low on toilet paper. “It wasn’t true at the time,” writes Steven, “but it quickly became true when viewers, knowing how many other Americans were viewers, snapped up the supply.” Ever since, the common knowledge that toilet paper is scarce during emergencies causes people to buy it in bulk, which makes toilet paper scarce during emergencies.

The book is full of recursive examples like this that make your head hurt while revealing deep insights about how we communicate. There aren’t many other mainstream books about this topic, and it provides a kind of groundbreaking way of thinking about human behavior. (Steven sent me an early copy of the book, and I enjoyed it so much that I provided a blurb for the cover.)

The chapter that interested me most is about one of my favorite topics: philanthropy. Steven and his colleagues ran numerous experiments to learn how people feel about different kinds of philanthropy. They found that people see anonymous giving as significantly more virtuous than public giving. As soon as a donation becomes common knowledge, it becomes less impressive. This belief is so strong that some participants in Steven’s research believed a smaller amount given anonymously was better than a larger amount given publicly.

I think there are a lot of practical reasons to be open about your giving, including the fact it creates transparency. But it was helpful to understand more about how people see philanthropy—and how those beliefs might shape their motivations for donating. I spend a lot of time encouraging other wealthy people to give away their money. This book armed me with new information that will (hopefully) make those conversations more effective moving forward.

Most people would benefit from understanding how common knowledge props up every conversation we have. “Human social life can seem baffling,” Steven writes. “It is played out with rituals and symbols and ceremonies, rife with social paradoxes and strategic absurdities… [but] life provides people with opportunities to flourish if they coordinate their actions.” If you are interested in learning more about how humans communicate and work together, I highly recommend reading When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Diller instinct

The man who built modern media

Barry Diller’s memoir is a candid playbook for creativity and competition in business.

If you don’t know Barry Diller’s name, you definitely know his work.

He invented the made-for-TV movie and the TV miniseries. He greenlit Raiders of the Lost Ark, An Officer and a Gentleman, Grease, Saturday Night Fever, Terms of Endearment, and the Star Trek movies. He created the Fox television network and helped bring the world The Simpsons. He turned QVC into a home shopping behemoth. He assembled a digital empire that built or grew Expedia, Match.com, Ticketmaster, Vimeo, and many more companies now part of everyday online life.

And that’s just scratching the surface.

I’m lucky to call Barry a friend, and I thought I knew his story. But his new memoir Who Knew still managed to surprise and teach me a lot about him, his career, and the many industries he’s transformed.

The book opens with Barry’s complicated childhood in Beverly Hills. From the outside, his family life looked idyllic. But his brother struggled with addiction; his parents, though loving, were often emotionally distant and preoccupied. Meanwhile, Barry was grappling with his sexuality in an age when being gay meant living in constant fear of exposure.

This part of Who Knew is raw and honest in a way most business memoirs usually aren’t. But Barry’s early years are key to understanding not just who he became as a person but also how he succeeded professionally. Reading the book, you can see how the same coping mechanisms he developed as a kid—learning to read people, defuse tension, compartmentalize, adapt—evolved into business instincts later on.

After barely graduating high school, Barry started in the mailroom of William Morris, a talent agency, at 19. Most people trying to break into Hollywood treat the mailroom as a stepping stone. The goal is to get out fast, become someone’s assistant, then get promoted to agent yourself. But Barry spent years there by choice, reading every contract and deal memo in the agency’s history. (His obsessive self-education reminded me of my own approach to learning.)

By the time he joined ABC at 23, he knew more about how the entertainment industry actually worked—the deal structures, the power dynamics, who mattered and why—than executives twice his age. That foundation let him revolutionize an industry in ways you can only do when you truly understand it.

At ABC, Barry came up with the made-for-TV movie: 90-minute films produced specifically for television, with different stories and casts each week. Within a year, ABC was producing 75 original movies annually. By 27, Barry was the youngest vice president in network television history. Then he created the miniseries.

Five years later, he was named chairman of Paramount Pictures, which had fallen to fifth place among the major movie studios. Barry rebuilt it into the number one studio by focusing on ideas first, not pre-packaged deals that came with the stars, directors, and writers already attached. He built a team of young executives and put them through what he called “creative conflict”: exhausting late-night sessions where his team would tear ideas apart to find their essence. Only if an idea survived that process would they develop it and then attach the right talent.

After leaving Paramount, Barry joined 20th Century Fox as chairman. But what he really wanted to do at Fox was create something that didn’t exist yet: a fourth national network to rival ABC, CBS, and NBC. That’s probably what surprised me most in the book—learning that Fox Broadcasting was Barry’s idea, not Rupert Murdoch’s. Barry had been pitching a fourth network for nearly a decade, even though conventional wisdom said that America could only support three networks. But Barry thought they’d become homogenous and identified an opening for something new. Eventually, he got Murdoch to agree.

That pattern shows up throughout the book. Barry is able to see opportunities that are invisible to everyone else and sound crazy until they don’t. When he left Fox at its peak to run QVC, people were baffled, including me. In reality, Barry had recognized that the future of commerce was hiding in plain sight, on a home shopping channel, where phone calls spiked in real-time as products were pitched on TV. This epiphany about interactivity—screens as two-way, not just passive—helped Barry do super well in the digital era.

Barry was early to see the internet’s potential and willing to bet on it when others weren’t. In 2001, he was in the process of buying Expedia from Microsoft when 9/11 happened and air travel grounded to a halt. He had an out clause but decided to go through with the acquisition anyway, betting that travel would come back. It did, and Expedia became one of the first major successes in what would become IAC: the unlikely conglomerate of 150+ internet businesses Barry assembled over the next two decades.

I’ve always wondered why one studio succeeds while another fails, and how revolutionary ideas get greenlit when conventional wisdom says they’re impossible. Barry provides a lot of insight, especially about media and entertainment, that I didn’t know before. He’s also candid about his failures: the disastrous stint running ABC’s prime-time programming, getting outmaneuvered in bidding wars, trusting the wrong people. I like that Barry doesn’t gloss over mistakes or reframe them as “learning experiences.” He just tells you he screwed up.

In his book, Barry attributes much of his success to luck and timing. But there’s a difference between being in the right place at the right time and knowing what to do once you’re there.

Who Knew? Barry did. He just had to wait for everyone else to catch up.

Permit pending

Why good ideas aren’t always enough

In Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson explain the bottlenecks that slow progress and what it’ll take to overcome them.

Back in 2007, the Gates Foundation and several partners tried something new. At the time, pneumonia was killing hundreds of thousands of kids in poor countries every year. The science to make a vaccine already existed, but pharmaceutical companies weren’t developing it for African strains of the virus because there was no obvious market to sell to.

So we made the companies a deal: If you build it, we’ll buy it. That promise, known as an Advance Market Commitment, led to the creation of affordable pneumonia vaccines that have saved an estimated 700,000 lives.

I was excited to see this story cited in Abundance, a recent book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson about why America struggles to build things and how we can do better. Their argument is that progress and innovation rely not just on good ideas but on systems—economic, political, and regulatory—that help those ideas spread and succeed. Today, those systems too often do the opposite. And good ideas end up slowed down or stonewalled instead.

Abundance is organized into five sections: Grow, Build, Govern, Invent, and Deploy. Each one examines a different bottleneck that gets in the way of getting stuff done.

The Grow section looks at how zoning and land-use rules have made housing scarce and expensive. Build focuses on the reasons it’s so hard to build the infrastructure the U.S. needs, especially for energy and transportation. Govern digs into why government has lost the capacity to make decisions and execute projects. Invent explores what drives scientific breakthroughs. And Deploy, where Klein and Thompson write about the pneumonia vaccines, examines what it will take to get more innovations from the lab into the real world. (An incentive structure like the Advanced Market Commitment is one of many potential solutions.)

I’ve spent a lot of time over the past two decades thinking about these problems. When I was running Microsoft, it was relatively easy to scale a good idea; if we built a better product, customers usually adopted it. But since I began working at the foundation full time, I’ve seen how the bottlenecks discussed in Abundance impede progress in global health—whether we’re trying to improve seeds, design better toilets, or eradicate polio. Sometimes the science itself is hard. But often, the logistics and execution are even harder.

That’s true in climate, too. Breakthrough Energy, which I helped launch in 2015, has backed hundreds of startups working on clean technologies. But getting those technologies to market is incredibly difficult—especially when it requires building new physical infrastructure. One of the biggest barriers to clean energy in the U.S. is the permitting process for long-distance transmission lines. Without them, we can’t upgrade our outdated grid to make it more affordable and reliable. But building them is slow and expensive.

Klein and Thompson dig into why this is. One of their recurring arguments is about government capacity. There was a time, especially in the mid-20th century, when government could make decisions and act on them—building highways, launching space programs, and approving major projects with clear timelines. Today, authority is spread across so many agencies and jurisdictions that even simple projects get stuck in limbo. And when they do move forward, there's a second problem: cost. America now spends exponentially more on infrastructure than other wealthy countries.

It's one thing to talk about these dynamics in the abstract. But Klein and Thompson show how they shape real-life outcomes in less obvious ways.

Take homelessness. A lot of people think mental illness or substance use are the main drivers. But the data tells a different story. While rates of addiction and mental illness are higher in West Virginia, California has much higher rates of homelessness—because housing costs are much higher. When you make it nearly impossible to build inexpensive housing through zoning rules, minimum lot sizes, or limits on shared bathrooms, then only expensive housing is built. The result is a shortage of everything else.

Abundance is tough on both sides of the aisle. The authors note how Republicans often rail against regulation while blocking government investments or gutting the institutions needed to do permitting well.

Klein and Thompson are liberals, though, and that’s who their primary message is for. They argue that Democrats—who tend to believe in government’s power to do good—have added layers of process and regulation that make it way too complex to actually get things done. But progress isn’t made by simply funding projects. It’s made by finishing them. And if you’re going to ask government to take on big challenges, you have to make sure it can deliver.

And we know it can. Our government is incredibly effective at building infrastructure and accelerating innovation when it wants to. Operation Warp Speed's development of COVID vaccines in record time is a perfect example. Democrats and Republicans alike should be competing to make this kind of thing happen more, not less.

Abundance doesn’t have all the answers. But in my view, Klein and Thompson are asking the right questions. I’m glad the book has already sparked some real debate, and I hope the conversation continues.

Climate matters

I loved this clear-eyed guide to global warming

Hannah Ritchie’s concise, reader-friendly Clearing the Air.

Climate change is one of the most important issues of our time and is causing enormous suffering, especially for the world’s poorest people. That makes it especially important for our conversations about climate to be grounded in facts. A few months ago I read a book that does an amazing job of that.

It's called Clearing the Air, and it’s the second book by data scientist Dr. Hannah Ritchie, a senior researcher at Our World in Data, an online platform that uses data to create super-clear visuals about global trends. (The Gates Foundation is one of their funders.) I’ve known and admired Hannah for several years. I learned about her work by reading her excellent first book, Not the End of the World, which argues that the global picture—in terms of health, poverty, the environment, and other measures—is a lot brighter than many people think. I liked it so much that I asked her to record an episode of my podcast with me.

Hannah brings the same spirit to Clearing the Air, which came out this year in the U.K. and will be published in the U.S. next March. She organizes it around fifty questions, like Isn’t nuclear power dangerous?, Is there any hope of low-carbon aviation and shipping?, and Aren’t renewables too expensive?

Her answers are a model of science writing for a general audience. She avoids jargon and keeps things concise—most chapters are only a couple of pages long, and each one starts with a summary that’s only one or two sentences long. For example, here’s her brief answer to a question about whether electric cars are too expensive for the average driver: “Electric cars are much cheaper to run, and will soon be just as cheap to buy upfront.” Over the next few pages, she explains why that’s true, but that single sentence is a memorable way to sum it all up.

She opens the book with a sharp question: Isn’t it too late? Aren’t we heading for a 5 or 6°C warmer world?. Here’s her short answer: “Every tenth of a degree matters. There’s no point at which it’s too late to limit warming and reduce damage from climate change.” After expanding on that answer, she turns to a bulleted list of three tips for talking about climate in a more helpful way.

First, she says, “be honest about where we’re heading…the 1.5°C target is dead.” Second, “don’t throw in the towel… Our 1.5°C and 2°C targets are not cliffs or thresholds.… Stop obsessing over arbitrary targets and focus on how you can help to reduce our carbon emissions as quickly as possible.” Finally, she suggests, “watch out for headlines based on worst-case scenarios. … Knowing the impacts of these extreme cases is useful for scientists, but not for policymakers or the public, who assume that this is the most likely outcome.”

One of the reasons we’re probably not headed for a worst-case scenario is that the energy transition is moving remarkably quickly in many areas. Hannah shows that solar and wind are scaling faster than any other energy source in history. In a single year, China built enough solar and wind capacity to power the entire United Kingdom, and half of the cars sold there are now electric.

Those are reasons to be optimistic, but not excuses to be complacent. We need to get renewables out there even faster, and we need to keep working on new breakthroughs like low-emissions steel, cement, and aviation fuel. These would be necessary even if there weren’t also the possibility that the climate will hit a tipping point and start warming faster than scientists are predicting now. Hannah has excellent chapters on each of those areas, and many others.

If I could add a 51st question to Hannah’s list, it would be: “Aren’t higher temperatures the biggest threat to mankind?” I’d love to hear her answer. Here’s mine: “Higher temperatures cause serious problems, especially in places with a lot of poverty and disease. The solution is to reduce emissions and also make sure people aren’t sick and poor.” I’m fortunate to be able to help on both fronts: lowering emissions by investing billions in clean-energy innovations, and fighting disease and poverty by giving away all my wealth through the Gates Foundation.

What I appreciate the most about Hannah is that she’s realistic about trade-offs and relentlessly focused on solving problems. As she writes toward the end of Clearing the Air, “The solutions we have today are as bad as they’ll ever be, and that’s a good thing.” They will only get better from here. That’s as true for vaccines and climate-smart seeds as it is for clean energy.

If you want a book that explains the climate challenge without doom or denial, Clearing the Air is a must-read. It’s a hopeful reminder that while the problem is enormous, the progress is real.

Starting line

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

The source code for Source Code

5 memoirs that helped shape my own

What I learned from other authors who wrote about their lives.

I feel like I’m always learning, but I really go into serious learning mode when I’m starting a new project. In the early days of Microsoft, I read a ton about technology companies, and as I was starting the Gates Foundation, I researched the history of American philanthropy.

Writing my memoir Source Code, which came out earlier this year, was no different: I thought about what I could draw on from the best memoirs I’ve read.

So for this year’s Summer Books, I want to share a few of them. With the exception of Nicholas Kristof’s Chasing Hope, I read all of these before finishing Source Code—in fact I read Katharine Graham’s Personal History years before I even decided to start writing. (Nick’s book is so good that I wanted to share it anyway.)

You won’t find a direct correlation between any of these books and Source Code. But I think it has shades of Bono’s vulnerability about his own challenges, Tara Westover’s evolving view of her parents, and Trevor Noah’s sense as a kid that he didn’t quite fit in.

In any case, I hope you can find something that interests you on this list. Memoirs are a good reminder that people have countless interesting stories to tell about their lives.

Personal History, by Katharine Graham. I met Kay Graham, the legendary publisher of the Washington Post, on July 5, 1991—the same day I met Warren Buffett—and we became good friends. I loved hearing Kay talk about her remarkable life: taking over the Post at a time when few women were in leadership positions like that, standing up to President Nixon to protect the paper’s reporting on Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, negotiating the end to a pressman’s strike, and much more. This thoughtful memoir is a good reminder that great leaders can come from unexpected places.

Chasing Hope, by Nicholas Kristof. In 1997, Nick Kristof wrote an article that changed the course of my life. It was about the huge number of children in poor countries who were dying from diarrhea—and it helped me decide what I wanted to focus my philanthropic giving on. I’ve been following Nick’s work ever since, and we’ve stayed in touch. He’s reported from more than 150 countries, covering war, poverty, health, and human rights. In this terrific memoir, Nick writes about how he stays optimistic about the world despite everything he’s seen. His book made me think: The world would be better off with more Nick Kristofs.

Educated, by Tara Westover. Tara grew up in a Mormon survivalist home in rural Idaho, raised by parents who believed that doomsday was coming and that the family should interact with the outside world as little as possible. Eventually she broke away from her parents—a process that felt like a much more extreme version of what I went through as a kid, and what I think a lot of people go through: At some point in your childhood, you go from thinking your parents know everything to seeing them as adults with limitations. Tara beautifully captures that process of self-discovery in this unforgettable memoir.

Born a Crime, by Trevor Noah. Back in 2017, I said this memoir shows how the former Daily Show host’s “approach has been honed over a lifetime of never quite fitting in.” I also grew up feeling like I didn’t quite fit in at times, although Trevor has a much stronger claim to the phrase than I do. He was a biracial child in apartheid South Africa, a country where mixed-race relationships were forbidden. He was, as the title says, “born a crime.” In this book, and in his comedy, Trevor uses his outside perspective to his advantage. His outlook transcends borders.

Surrender, by Bono. I’m lucky that my parents were super supportive of my interest in computers—but Bono’s parents had a very different view of his passion for singing. He says his parents basically ignored him, which made him try even harder to get their attention. “The lack of interest of my father … in his son’s voice is not easy to explain, but it might have been crucial.” Bono shows a lot of vulnerability in this surprisingly open memoir, writing about his “need to be needed” and how he learned he’ll never fill his emotional needs by playing for huge crowds. It was a great model for how I could be open about my own challenges in Source Code.

On the record

How Katharine Graham found the courage to challenge Nixon

Personal History contains valuable lessons about leadership and finding strength in vulnerability.

July 5, 1991 was one of the most important days of my life. My mom was hosting a get-together at our family’s favorite vacation spot in Hood Canal, WA. One of her friends had invited Warren Buffett, and I immediately hit it off with him, kickstarting a relationship that would, among other things, lead to the creation of the Gates Foundation.

But Warren wasn’t the only legend in the room. I remember him introducing me to his old friend Katharine Graham, one of the most well-respected newspaper publishers in the world. Even after all these years—and after her death in 2001—I still treasure the friendship I began with Kay that day.

Kay is best known for leading the Washington Post through the Watergate crisis, but her remarkable story goes way beyond her fights with the Nixon White House. That story is told in her riveting memoir Personal History, which came out in 1997—just a few years before she passed away—and won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Kay’s father purchased the Washington Post and saved it from bankruptcy when she was a teenager. In 1946, he made Kay’s husband, Philip Graham, the publisher of the paper. Although this decision sounds strange today—Why would you hand over the family business to your son-in-law instead of your own child?—the thought of putting a woman in charge was unthinkable in that era. “It never crossed my mind that he might have viewed me as someone to take on an important job at the paper,” she writes. Kay was expected to devote her life to being a good wife and mother.

But life with Phil wasn’t easy. He suffered from bipolar disorder at a time when treatments for mental illness were crude and ineffective. The chapters about his mental decline are devastating. Kay describes how Phil had to be sedated after suffering from a manic episode at a publishing conference. A few months later, he dies by suicide during a stay at the family’s country home. Kay is the first person to find his body.

While she was struggling with grief, Kay found herself thrust into a new role: president of the Washington Post Company and the publisher of a major national newspaper. That isn’t an easy job under any circumstances, but several of Kay’s male colleagues made it harder than it needed to be. “I didn’t blame my male colleagues for condescending—I just thought it was due to my being so new,” she writes. “It took the passage of time and the women’s lib years to alert me properly to the real problems of women in the workplace, including my own.”

Still, Kay internalized some of the skepticism, and she is pretty harsh on herself throughout the book. She blames herself for Phil’s suicide and describes her business acumen as “abysmally ignorant” when she takes over the Post. I understand her impulse to be critical of her younger self—I often felt frustrated by how I acted as a kid when I was writing my own memoir, Source Code. But it can be difficult to read at points in Personal History. I wish Kay knew how special she was.

Her story is a powerful reminder that strong leaders don’t always come in the form you expect. What Kay sees as weaknesses end up becoming her strengths. Because she didn’t know much about the newsroom when she took over in 1963, she asked a lot of questions. A more experienced publisher might have come into the job with preconceived notions about how to run things—but Kay listened to her new colleagues, and she took the time to learn how they worked. That trust in her people would pay off years later during the Watergate scandal.

I was a teenager during the Watergate years, and I remember reading about it in the paper. Many people focus on two specific events when they talk about Watergate: the break-in at the Democratic National Committee in June 1972, and President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 after secret recordings revealed his administration’s involvement in the burglary and subsequent cover-up. But during the more than two years between those two points, the Washington Post reported relentlessly on the scandal.

Nixon himself tried to bully them into giving up, but Kay stood by her newsroom. She protected their editorial independence, never asking her reporters to censor or soften their reporting. At one point, John Mitchell—the chair of Nixon’s re-election campaign and former Attorney General—told a Post reporter that Kay was going to get a certain part of her anatomy “caught in a big fat ringer.” She read about it in the paper the next day.

Kay risked the company’s reputation and financial health to protect journalistic integrity, even in the face of potential lawsuits and calls to discredit the paper. The Post almost folded at one point when the Nixon administration threatened to pull the broadcasting licenses for several TV stations owned by the Washington Post Company. (Despite being the namesake of the company, the Washington Post itself was not profitable at the time. The business relied on local broadcast stations to stay afloat.)

This is where Warren enters the story. He believed the Washington Post was undervalued, and in 1973, Berkshire Hathaway bought a 10 percent ownership share—enough to keep the company going while making sure that Kay remained in control. He eventually became a trusted advisor and a close friend to Kay, which I saw firsthand years later in Hood Canal.

Warren has always hated that Kay was left out of the movie All the President’s Men, which came out just two years after Nixon resigned and received great critical acclaim. Without her leadership and bravery, the Watergate scandal might have faded into obscurity. Fortunately, the film The Post gave Kay her proper due. Meryl Streep was even nominated for an Oscar for playing her.

There is so much to Kay’s story—including her time with President Kennedy, the Pentagon Papers, and the pressmen’s strike—that I cannot mention all of it here. If you want to learn even more about her incredible life, I recommend starting with the new documentary Becoming Katharine Graham before reading Personal History.

Diving deep into Kay's extraordinary life is well worth your time. Her story offers more than just insights into a fascinating chapter of American history—it also reveals valuable lessons about courage, leadership, and finding strength in vulnerability.

Field notes

The world needs more Nick Kristofs

I loved this journalist’s story of chasing hard problems and holding onto hope.

If you’re a big reader, you can probably point to a book or two that changed the course of your life. For me, it was a 1997 New York Times column by Nicholas Kristof about diarrhea, which was killing three million kids a year.

At the time, I had wealth—and knew I planned to give it away—but no clear mission. Nick’s article gave me one. I faxed it to my dad with a note: “Maybe we can do something about this.”

That ended up setting the direction for what became the Gates Foundation. It didn’t just give us a what—it gave us a how. Nick’s reporting showed us that the biggest challenge in global health isn’t always discovering new breakthroughs. Often, it’s making sure the tools we already have—vaccines, medicines, bed nets, or oral rehydration therapies for rotavirus—reach every child, no matter where they’re born.

Reading Nick’s new memoir, Chasing Hope, brought me back to that moment and showed me how it fit into the bigger story of his life. The book is a deeply personal account of a life spent documenting injustice and refusing to look away, whether it’s genocide in Darfur, refugee camps in Sudan, or the streets of his hometown in rural Oregon.

Nick’s impulse to go where the suffering is, and to make people care, has defined his career. He’s reported from more than 150 countries, covering war, poverty, health, and human rights. He and his longtime collaborator and wife, Sheryl WuDunn, won a Pulitzer Prize for their work. Together and individually, they’ve brought injustices around the world into view for millions of readers.

But Chasing Hope isn’t just a greatest-hits collection of his past reporting. It’s the story of how someone becomes Nick Kristof. He writes about growing up on a sheep and cherry farm in Oregon, driving tractors as a teenager, and nearly becoming a lawyer before deciding on journalism. He also reflects on the toll his career has taken on him, his family, and his capacity for hope.

I’ve known Nick for many years now, and I’ve admired his work since that 1997 rotavirus column. On paper, we don’t seem all that similar. He’s a journalist, I’m a technologist; he tells stories, I talk numbers. But reading Chasing Hope, I was struck by what we have in common: growing up in the Pacific Northwest, learning about the value of service from our parents, thinking globally.

We both attended Harvard and left early—me because I dropped out, him because he graduated in three years before heading to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. But neither of us ever stopped learning. I think we both believe the world’s pretty interesting if you remain a student.

Nick’s curiosity didn’t come out of nowhere, and neither did his sense of purpose. His mother was an art history professor and a civic leader who helped influence local politics. His father, a political science professor who fled both Nazism and communism, believed deeply in education and the responsibilities that come with freedom. That kind of upbringing left a mark on him and shaped the kind of journalist he became.

Over decades, he’s built a career reporting on crises that are often ignored because they happen in far-off places, far from centers of power. In Chasing Hope, he recounts his experiences chronicling river blindness in Ethiopia, maternal mortality in Cameroon, and malaria in Cambodia. Through the foundation, I mobilize science, data, and funding to address many of the same global challenges Nick reports on. Our approaches are different, but the underlying questions we ask (and try to answer) are the same: Why are some lives valued less than others? And how can we use the tools we have—information, resources, attention—to close that gap?

Nick has an admirable commitment to nuance, especially when it comes to hard subjects like China. Nick lived there for years, speaks Mandarin, and understands the country in a way most Western commentators don’t. I’ve always appreciated his ability to go beyond the headlines—and focus not just on what’s going wrong, but on what’s changing and why it matters.

Nick is also an optimist, which might sound strange given the kinds of suffering he writes about. But his work is grounded in a belief I share: The right data—or the right story—can move people to act. As Nick puts it, “A central job of a journalist is to get people to care about some problem that may seem remote.” People, when given the chance, want to make things better. Progress, while never guaranteed, is possible.

That optimism feels especially important, if increasingly difficult, right now. Isolationism is on the rise around the world, and governments are cutting back on foreign aid at the very moment when we should be doing more, not less. Millions of lives are at stake. Nick’s work reminds us what’s possible when we care about people beyond our own borders—and what happens when we don’t.

Chasing Hope made me think a lot about what kind of person chooses to run toward the hardest problems—and keep going back until they’re solved. It also made me think the world would be a much better place if there were more Nick Kristofs. In the meantime, we’re lucky to have this one.

Quest for knowledge

Educated is even better than you’ve heard

I loved Tara Westover’s journey from the mountains of Idaho to the halls of Cambridge.

I’ve always prided myself on my ability to teach myself things. Whenever I don’t know a lot about something, I’ll read a textbook or watch an online course until I do.

I thought I was pretty good at teaching myself—until I read Tara Westover’s memoir Educated. Her ability to learn on her own blows mine right out of the water. I was thrilled to sit down with her recently to talk about the book.

Tara was raised in a Mormon survivalist home in rural Idaho. Her dad had very non-mainstream views about the government. He believed doomsday was coming, and that the family should interact with the health and education systems as little as possible. As a result, she didn’t step foot in a classroom until she was 17, and major medical crises went untreated (her mother suffered a brain injury in a car accident and never fully recovered).

Because Tara and her six siblings worked at their father’s junkyard from a young age, none of them received any kind of proper homeschooling. She had to teach herself algebra and trigonometry and self-studied for the ACT, which she did well enough on to gain admission to Brigham Young University. Eventually, she earned her doctorate in intellectual history from Cambridge University. (Full disclosure: she was a Gates Scholar, which I didn’t even know until I reached that part of the book.)

Educated is an amazing story, and I get why it’s spent so much time on the top of the New York Times bestseller list. It reminded me in some ways of the Netflix documentary Wild, Wild Country, which I recently watched. Both explore people who remove themselves from society because they have these beliefs and knowledge that they think make them more enlightened. Their belief systems benefit from their separateness, and you’re forced to be either in or out.

But unlike Wild, Wild Country—which revels in the strangeness of its subjects—Educated doesn’t feel voyeuristic. Tara is never cruel, even when she’s writing about some of her father’s most fringe beliefs. It’s clear that her whole family, including her mom and dad, is energetic and talented. Whatever their ideas are, they pursue them.

Of the seven Westover siblings, three of them—including Tara—left home, and all three have earned Ph.D.s. Three doctorates in one family would be remarkable even for a more “conventional” household. I think there must’ve been something about their childhood that gave them a degree of toughness and helped them persevere. Her dad taught the kids that they could teach themselves anything, and Tara’s success is a testament to that.

I found it fascinating how it took studying philosophy and history in school for Tara to trust her own perception of the world. Because she never went to school, her worldview was entirely shaped by her dad. He believed in conspiracy theories, and so she did, too. It wasn’t until she went to BYU that she realized there were other perspectives on things her dad had presented as fact. For example, she had never heard of the Holocaust until her art history professor mentioned it. She had to research the subject to form her own opinion that was separate from her dad’s.

Her experience is an extreme version of something everyone goes through with their parents. At some point in your childhood, you go from thinking they know everything to seeing them as adults with limitations. I’m sad that Tara is estranged from a lot of her family because of this process, but the path she’s taken and the life she’s built for herself are truly inspiring.

When you meet her, you don’t have any impression of all the turmoil she’s gone through. She’s so articulate about the traumas of her childhood, including the physical abuse she suffered at the hands of one brother. I was impressed by how she talks so candidly about how naïve she once was—most of us find it difficult to talk about our own ignorance.

I was especially interested to hear her take on polarization in America. Although it’s not a political book, Educated touches on a number of the divides in our country: red states versus blue states, rural versus urban, college-educated versus not. Since she’s spent her whole life moving between these worlds, I asked Tara what she thought. She told me she was disappointed in what she called the “breaking of charity”—an idea that comes from the Salem witch trials and refers to the moment when two members of the same group break apart and become different tribes.

“I worry that education is becoming a stick that some people use to beat other people into submission or becoming something that people feel arrogant about,” she said. “I think education is really just a process of self-discovery—of developing a sense of self and what you think. I think of [it] as this great mechanism of connecting and equalizing.”

Tara’s process of self-discovery is beautifully captured in Educated. It’s the kind of book that I think everyone will enjoy, no matter what genre you usually pick up. She’s a talented writer, and I suspect this book isn’t the last we’ll hear from her. I can’t wait to see what she does next.

Universal humor

Chameleon comic

Trevor Noah’s funny and moving account of growing up in South Africa.

I’m a longtime fan of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. When Jon Stewart stepped down as host in 2015, I was sad to see him go. I was also worried for his replacement, Trevor Noah, a South African comedian. Stewart’s style is so unusual that I didn’t see how anyone could fill his shoes—especially someone like Noah, who describes himself as an outsider. As popular as Noah was in South Africa, I didn’t know whether his humor would connect with American audiences.

I’m happy to report that I was wrong. Millions of viewers—myself included—are tuning in to The Daily Show because Noah’s show is every bit as good as Stewart’s. His humor has a lightness and optimism that’s refreshing to watch. What’s most impressive is how he uses his outside perspective to his advantage. He’s good at making fun of himself, America, and the rest of the world. His comedy is so universal that it has the power to transcend borders.

Reading Noah’s memoir, Born a Crime, I quickly learned how Noah’s outsider approach has been honed over a lifetime of never quite fitting in. Born to a black South African mother and a white Swiss father in apartheid South Africa, he entered the world as a biracial child in a country where mixed race relationships were forbidden. Noah was not just a misfit, he was (as the title says) “born a crime.”

In South Africa, where race categories are so arbitrary and yet so prominent, Noah never had a group to call his own. As a little boy living under apartheid laws, he couldn’t be seen in public with his white father or his black mother. In public, his father would walk far ahead of him to ensure he wouldn’t be seen with his biracial son. His mother would pose as a maid to make it look like she was just babysitting another family’s child. On the schoolyard, he didn’t fit in with the white kids or the black kids or the kids who were “colored” (the term used in South Africa to describe people of mixed race).

But during his childhood, he quickly discovered that there’s a freedom that comes with being a misfit. A polyglot who speaks English, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu, Tsonga, Tswana, as well as German and Spanish, Noah used his talent for language to bounce from group to group and win acceptance from all of them. One of my favorite stories in the book involves Noah walking down the street when he overhears a group of men speaking in Zulu about how they were plotting to mug “this white guy.” Noah realizes they were referring to him. Noah spins around and announces in perfect Zulu that they should all mug someone together. The Zulu men are startled that Noah speaks Zulu and a tense situation is defused. Noah is immediately accepted as one of their own.

Again and again throughout his childhood, he discovered that language was more powerful than skin color in building connections with other people. “I became a chameleon,” Noah writes. “My color didn’t change, but I could change your perception of my color. If you spoke to me in Zulu, I replied to you in Zulu. If you spoke to me in Tswana, I replied to you in Tswana. Maybe I didn’t look like you, but if I spoke like you, I was you.”

Much of Noah’s story of growing up in South Africa is tragic. His Swiss father moves away. His family is desperately poor. He’s arrested. And in the most shocking moment, his mother is shot by his stepfather. Yet in Noah’s hands, these moving stories are told in a way that will often leave you laughing. His skill for comedy is clearly inherited from his mother. Even after she’s shot in the face, and miraculously survives, she tells her son from her hospital bed to look at the bright side. “’Now you’re officially the best-looking person in the family,’” she jokes.

In fact, Noah’s mother emerges as the real hero of the book. She’s an extraordinary person who is fiercely independent and raised her son to be the same way. Her greatest gift was to give her son the ability to think for himself and see the world from his own perspective. “If my mother had one goal, it was to free my mind,” he writes. Like many fans of Noah’s, I am thankful she did.

Surrender

The best memoir by a rock star I actually know

I’m lucky to call Bono a friend. But his autobiography still surprised me.

When Paul Hewson was 11, his parents sent him to a Dublin grammar school that happened to have an outstanding boys’ choir. Paul, who later took the nickname Bono, loved singing. His father had a beautiful voice, and Paul thought he might have some of his dad’s talent. But when the principal asked him if he wanted to join the choir, his mom jumped in before he could answer. “Not at all,” she said. “Paul has no interest in singing.”

Bono’s new book, Surrender, is packed with funny, poignant moments like this. Even though I’m a big fan of U2, and Bono and I have become friends over the years—Paul Allen connected us in the early 2000s—a lot of those stories were new to me. I went into this book knowing almost nothing about his anger at his father, the band’s near-breakups, and his discovery that his cousin was actually his half-brother. I didn’t even know that he grew up with a Protestant mom and Catholic dad.

I loved Surrender. You get to observe the band in the process of creating some of their most iconic songs. The book is filled with clever, self-deprecating lines like “Just how effective can a singer with anger issues be in the cause of nonviolence?” And you’ll learn a lot about the challenges he dealt with in his campaigns for debt relief and HIV treatment in Africa. (The Gates Foundation is a major supporter of ONE, the nonprofit that Bono helped start.)

In this passage, he explains how a boy from the suburbs of Dublin became a global phenomenon: “There are only a few routes to making a grandstanding stadium singer out of a small child. You can tell them they’re amazing, that the world needs to hear their voice, that they must not hide their ‘genius under a bushel.’ Or you can just plain ignore them. That might be more effective. The lack of interest of my father, a tenor, in his son’s voice is not easy to explain, but it might have been crucial.” (It also helped that he has, as he later learned from a doctor, freakishly large lung capacity.)

Bono’s loyalty to his bandmates, and their loyalty to him, is pretty incredible. My favorite illustration from the book takes place at a concert in Arizona, when the band was urging the then-governor to uphold the national MLK Day holiday in his state. U2’s security team picked up a credible threat to Bono’s life if the band played their Martin Luther King tribute “Pride (In the Name of Love).” “It wasn’t just melodrama,” he writes, “when I closed my eyes and sort of half kneeled to disguise the fact that I was fearful to sing the rest of the words.” When Bono opened his eyes, he saw that bassist Adam Clayton had moved in front of him to shield him like a Secret Service agent. Fortunately, the threat never materialized.

There’s another factor that explains the band’s tight bonds: They share the same values. All four of them are passionate about fighting poverty and inequity in the world, and they’re also aligned on maintaining their integrity as artists. I learned this the hard way. When Microsoft wanted to license U2’s song “Beautiful Day” for an ad campaign, I joined a call in an attempt to persuade the band to go for the deal. They simply weren’t interested. I admired their commitment.

While Bono never got lost in drugs or alcohol, he acknowledges that stardom gave him a big ego. He also says that he had a “need to be needed.” His key to survival was embracing the concept of spiritual surrender, as the title of the book suggests. He eventually came to see that he’d never fill his emotional needs by playing for huge crowds or being a global advocate. His faith in a higher power helped him a lot. So did his wife, Ali. He writes that when his mom died during his childhood, his home “stopped being a home; it was just a house.” Ali and their four children gave him a home once again.

Bono writes that his surrender is still incomplete. He’s not going to retire anytime soon, which is great news and not just for U2 fans. After the past few years, the field of global health—one of his chief causes—needs an injection of energy and passion. Bono’s unique gifts are perfectly suited to that mission.

Food for thought

What it will really take to feed the world

In his latest book, one of my favorite authors argues that solving hunger requires more than producing more food.

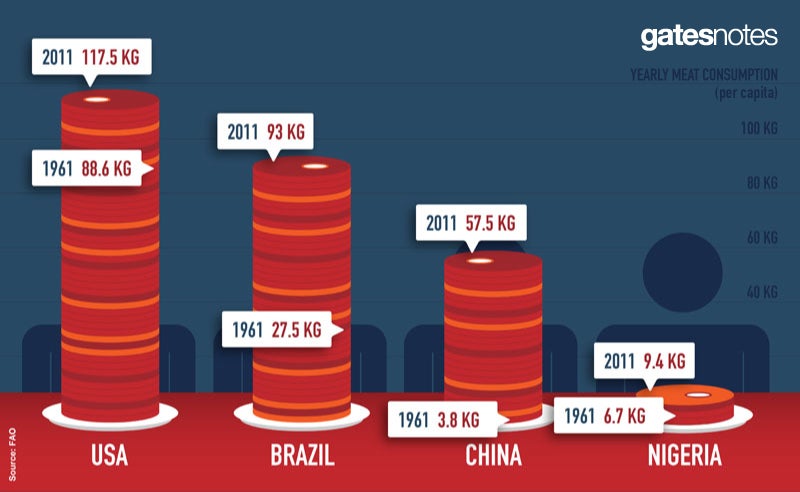

In the introduction to his latest book, How to Feed the World, Vaclav Smil writes that “numbers are the antidote to wishful thinking.” That one line captures why I’ve been such a devoted reader of this curmudgeonly Canada-based Czech academic for so many years. Across his decades of research and writing, Vaclav has tackled some of the biggest questions in energy, agriculture, and public health—not by making grand predictions, but by breaking down complex problems into measurable data.

Now, in How to Feed the World, Vaclav applies that same approach to one of the most pressing issues of our time: ensuring that everyone has enough nutritious food to eat. Many discussions about feeding the world focus on increasing agricultural productivity through improved seeds, healthier soils, better farming practices, and more productive livestock (all priorities for the Gates Foundation). Vaclav, however, insists we already produce more than enough food to feed the world. The real challenge, he says, is what happens after the food is grown.

This kind of argument is classic Vaclav—questioning assumptions, forcing us to rethink the way we frame problems, and turning conventional wisdom on its head. His analysis is never about the best- or worst-case scenarios; it’s about what the numbers actually tell us.

And the numbers tell a striking story: Some of the world’s biggest food producers have the highest rates of undernourishment. Globally, we produce around 3,000 calories per person per day—more than enough to feed everyone—but a staggering one-third of all food is wasted. (In some rich countries, that figure climbs to 45 percent.) Distribution systems fail, economic policies backfire, and food doesn’t always go where it’s needed.

I’ve seen this firsthand through the Gates Foundation’s work in sub-Saharan Africa, where food insecurity is driven by low agricultural productivity and weak infrastructure. Yields in the region remain far lower than in Asia or Latin America, in part because farmers rely on rain-fed agriculture rather than irrigation and have limited access to fertilizers, quality seeds, and digital farming tools. But even when food is grown, getting it to market is another challenge. Poor roads drive up transport costs, inadequate storage leads to food going bad, and weak trade networks make nutritious food unaffordable for many families.

And access is only part of the problem. Even when people get enough calories, they’re often missing the right nutrients. Malnutrition remains one of the most critical challenges the foundation works on—and it’s more complex than eating enough food. While severe hunger has declined globally, micronutrient deficiencies remain stubbornly common, even in wealthy countries. One of the most effective solutions has been around for nearly a century: food fortification. In the U.S., flour has been fortified with iron and vitamin B since the 1940s. This simple step has helped prevent conditions like anemia and neural tube defects and improve public health at scale—close to vaccines in terms of lives improved per dollar spent.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is Vaclav’s exploration of how human diets evolved. Across civilizations, people independently discovered that pairing grains with legumes created complete protein profiles—whether it was rice and soybeans in Asia, wheat and lentils in India, or corn and beans in the Americas. These solutions emerged from practical experience long before modern science could explain why they worked so well.

But just as past generations adapted their diets to available resources, we’re now facing new challenges that require us to adapt in different ways. Technology and innovation can help. They’ve already transformed the way we produce food, and they’ll continue to play a role. Take aquaculture: Once a tiny industry, it’s grown over the past 40 years to supply more seafood for the world than traditional fishing—a scalable way to meet global protein demands. The Green Revolution is another example. Beginning in the 1960s, innovations in higher-yielding crops, more effective fertilizers, and modern irrigation prevented widespread famine in India and Mexico. These changes were once seen as unlikely, too.

New breakthroughs could drive even more progress. CRISPR gene editing, for instance, could help develop crops that are more resilient to drought, disease, and pests—critical for farmers facing the pressures of climate change. Vaclav warns that we can’t count on technological miracles alone, and I agree. But I also believe that breakthroughs like CRISPR could be game-changing, just as the Green Revolution once was. The key is balancing long-term innovation with practical solutions we can implement immediately.

And some of these solutions aren’t about producing more food at all—they’re about wasting less of what we already have. Better storage and packaging, smarter supply chains, and flexible pricing models could significantly reduce spoilage and excess inventory. In a conversation we had about the book, Vaclav pointed out that Costco (which might seem like the pinnacle of U.S. consumption) stocks fewer than 4,000 items, compared to 40,000-plus in a typical North American supermarket.

That kind of efficiency—focusing on fewer, high-turnover products—reduces waste, lowers costs, and ultimately eases pressure on global food supply, helping make food more affordable where it is needed most.

How to Feed the World had a lot to teach me—and I’m sure it will teach you a lot, too. Like all of Vaclav’s best books, it challenges readers to think differently about a problem we thought we understood. Growing more and better food remains crucial—especially in places like sub-Saharan Africa, where there simply isn’t enough. But as the world’s population approaches 10 billion, increasing agricultural productivity alone won’t solve hunger and malnutrition. We also need to ensure that food is more accessible and affordable, less wasted, and just as nutritious as it is abundant.

After all, the goal isn’t to make more food for its own sake—it’s to feed more people.

The Smil test

Three cheers for the dull, factually correct middle

A new masterpiece from one of my favorite authors.

I occasionally check the bestseller lists for ideas about what to read next. A few weeks ago I looked at the New York Times’s nonfiction list and got quite a surprise. The latest book by Vaclav Smil, How the World Really Works, was number 8!

I have been a fan of Vaclav’s work for years—he is one of my favorite authors. But his style is not for everyone. Many of his books are dense and packed with data, and it is an understatement to say they have never sold especially well. So as an admirer of Vaclav’s work, I was excited to see his latest one in the top 10 list. The more people who read his books, the better. (I’m sure his new book got a boost from this largely positive review in the New York Times Book Review.)

What I love about How the World Really Works is that it sums up all of the incredible knowledge Vaclav has gained over the years. Most of his 50 books go into great detail about complex subjects including energy, manufacturing, shipping, and agriculture. He wrote an entire book on how diets in Japan have changed.

Because he has gone so deep into such specific topics, he is qualified to step back and write a broad overview for a general audience, which is what he has done with How the World Really Works. If you want a brief but thorough education in numeric thinking about many of the fundamental forces that shape human life, this is the book to read.

Energy is a great example. I have learned more about energy and its impact on society from Vaclav than from any other single source. In 2017 I reviewed his masterpiece Energy and Civilization: A History and wrote that “he goes deep and broad to explain how innovations in humans’ ability to turn energy into heat, light, and motion have been a driving force behind our cultural and economic progress over the past 10,000 years.”

But if you are not up for a long, dense book on the role of energy in human history—Energy and Civilization is 568 pages long and reads like an academic text—you can get the most important ideas by reading the first three chapters of How the World Really Works. They should be required reading for anyone who wants to have an informed opinion on climate change. All Vaclav wants is for people to look at all the areas of emissions—producing electricity, manufacturing, transportation, and so on—and propose realistic, economically viable plans for reducing emissions in each one.

As I wrote in my book on climate change, parts of which drew on Vaclav’s work, I am more optimistic than he is about the opportunity to innovate our way out of a climate disaster. But I highly recommend reading him on the subject because he is so good at explaining how the world’s energy systems work today. Chapter 1, which you can download for free below, is a great example—it covers fuels and the production of electricity.

Another good example of Vaclav’s approach is from the chapter on food. To help you understand the ways in which new sources of energy have allowed humans to grow crops and raise animals more efficiently, he portrays life on three different farms from three eras. He starts with a hypothetical farmer in western New York state in 1801 and explains all the laborious steps required for that person to harvest wheat. Then he skips ahead a century and takes you to eastern North Dakota, showing you all the advances, including plows and harvesters, that made farming far more efficient. Finally he goes to Kansas in 2021 and shows you how things have changed even more dramatically in the past century.

As usual, Vaclav has crunched all the numbers, so he can explain all of this change in both qualitative and quantitative ways. “In two centuries,” he writes, “the human labor to produce a kilogram of American wheat was reduced from 10 minutes to less than two seconds.”

And then he puts that statistic in an even broader context, showing how higher crop yields freed up people to move off of farms and into urban areas where they could collaborate on other innovations. “Most of the admired and undoubtedly remarkable technical advances that have transformed industries, transportation, communication, and everyday living,” he writes, “would have been impossible if more than 80 percent of all people had to remain in the countryside in order to produce their daily bread… or their daily bowl of rice.”