On the record

How Katharine Graham found the courage to challenge Nixon

Personal History contains valuable lessons about leadership and finding strength in vulnerability.

July 5, 1991 was one of the most important days of my life. My mom was hosting a get-together at our family’s favorite vacation spot in Hood Canal, WA. One of her friends had invited Warren Buffett, and I immediately hit it off with him, kickstarting a relationship that would, among other things, lead to the creation of the Gates Foundation.

But Warren wasn’t the only legend in the room. I remember him introducing me to his old friend Katharine Graham, one of the most well-respected newspaper publishers in the world. Even after all these years—and after her death in 2001—I still treasure the friendship I began with Kay that day.

Kay is best known for leading the Washington Post through the Watergate crisis, but her remarkable story goes way beyond her fights with the Nixon White House. That story is told in her riveting memoir Personal History, which came out in 1997—just a few years before she passed away—and won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Kay’s father purchased the Washington Post and saved it from bankruptcy when she was a teenager. In 1946, he made Kay’s husband, Philip Graham, the publisher of the paper. Although this decision sounds strange today—Why would you hand over the family business to your son-in-law instead of your own child?—the thought of putting a woman in charge was unthinkable in that era. “It never crossed my mind that he might have viewed me as someone to take on an important job at the paper,” she writes. Kay was expected to devote her life to being a good wife and mother.

But life with Phil wasn’t easy. He suffered from bipolar disorder at a time when treatments for mental illness were crude and ineffective. The chapters about his mental decline are devastating. Kay describes how Phil had to be sedated after suffering from a manic episode at a publishing conference. A few months later, he dies by suicide during a stay at the family’s country home. Kay is the first person to find his body.

While she was struggling with grief, Kay found herself thrust into a new role: president of the Washington Post Company and the publisher of a major national newspaper. That isn’t an easy job under any circumstances, but several of Kay’s male colleagues made it harder than it needed to be. “I didn’t blame my male colleagues for condescending—I just thought it was due to my being so new,” she writes. “It took the passage of time and the women’s lib years to alert me properly to the real problems of women in the workplace, including my own.”

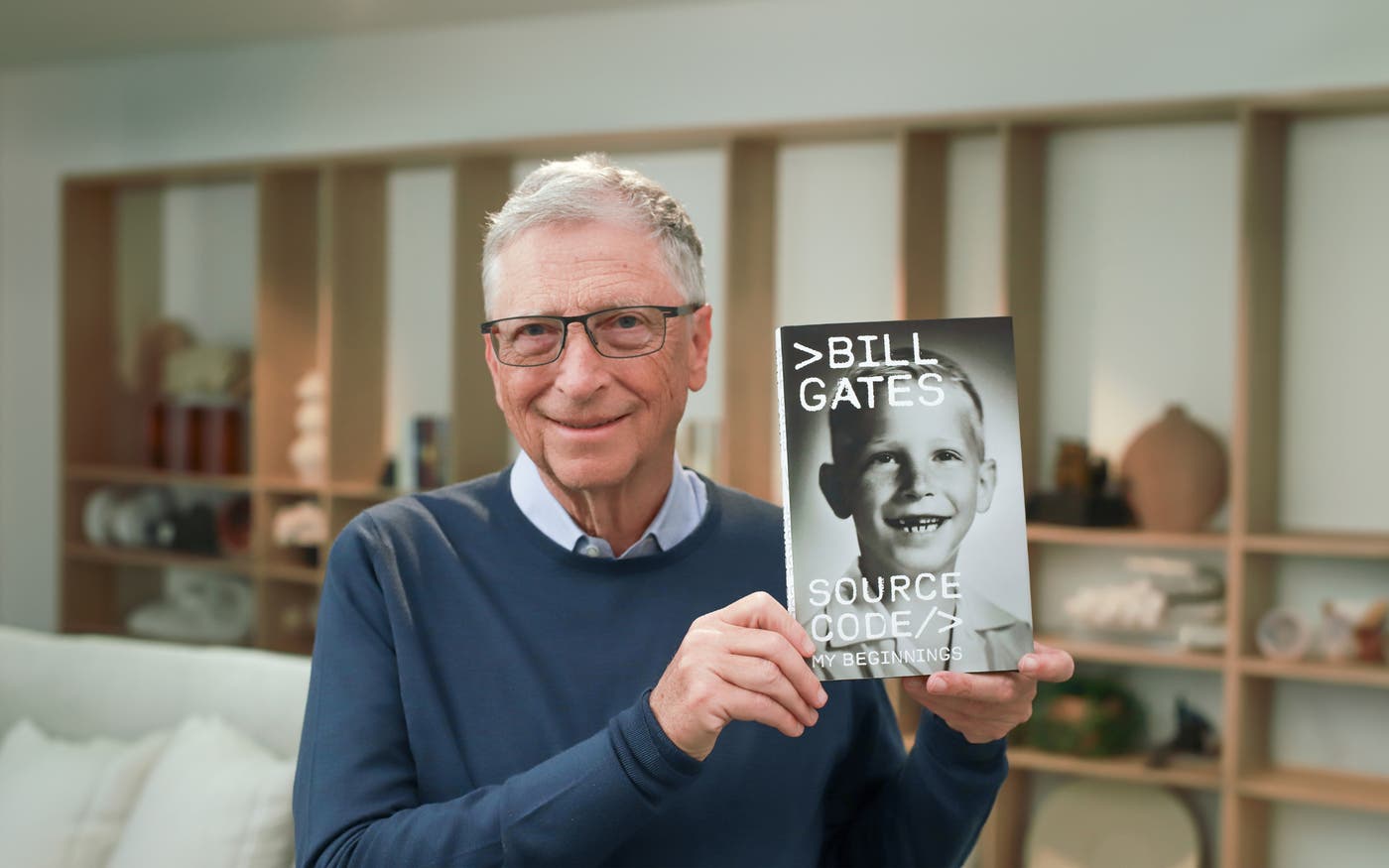

Still, Kay internalized some of the skepticism, and she is pretty harsh on herself throughout the book. She blames herself for Phil’s suicide and describes her business acumen as “abysmally ignorant” when she takes over the Post. I understand her impulse to be critical of her younger self—I often felt frustrated by how I acted as a kid when I was writing my own memoir, Source Code. But it can be difficult to read at points in Personal History. I wish Kay knew how special she was.

Her story is a powerful reminder that strong leaders don’t always come in the form you expect. What Kay sees as weaknesses end up becoming her strengths. Because she didn’t know much about the newsroom when she took over in 1963, she asked a lot of questions. A more experienced publisher might have come into the job with preconceived notions about how to run things—but Kay listened to her new colleagues, and she took the time to learn how they worked. That trust in her people would pay off years later during the Watergate scandal.

I was a teenager during the Watergate years, and I remember reading about it in the paper. Many people focus on two specific events when they talk about Watergate: the break-in at the Democratic National Committee in June 1972, and President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 after secret recordings revealed his administration’s involvement in the burglary and subsequent cover-up. But during the more than two years between those two points, the Washington Post reported relentlessly on the scandal.

Nixon himself tried to bully them into giving up, but Kay stood by her newsroom. She protected their editorial independence, never asking her reporters to censor or soften their reporting. At one point, John Mitchell—the chair of Nixon’s re-election campaign and former Attorney General—told a Post reporter that Kay was going to get a certain part of her anatomy “caught in a big fat ringer.” She read about it in the paper the next day.

Kay risked the company’s reputation and financial health to protect journalistic integrity, even in the face of potential lawsuits and calls to discredit the paper. The Post almost folded at one point when the Nixon administration threatened to pull the broadcasting licenses for several TV stations owned by the Washington Post Company. (Despite being the namesake of the company, the Washington Post itself was not profitable at the time. The business relied on local broadcast stations to stay afloat.)

This is where Warren enters the story. He believed the Washington Post was undervalued, and in 1973, Berkshire Hathaway bought a 10 percent ownership share—enough to keep the company going while making sure that Kay remained in control. He eventually became a trusted advisor and a close friend to Kay, which I saw firsthand years later in Hood Canal.

Warren has always hated that Kay was left out of the movie All the President’s Men, which came out just two years after Nixon resigned and received great critical acclaim. Without her leadership and bravery, the Watergate scandal might have faded into obscurity. Fortunately, the film The Post gave Kay her proper due. Meryl Streep was even nominated for an Oscar for playing her.

There is so much to Kay’s story—including her time with President Kennedy, the Pentagon Papers, and the pressmen’s strike—that I cannot mention all of it here. If you want to learn even more about her incredible life, I recommend starting with the new documentary Becoming Katharine Graham before reading Personal History.

Diving deep into Kay's extraordinary life is well worth your time. Her story offers more than just insights into a fascinating chapter of American history—it also reveals valuable lessons about courage, leadership, and finding strength in vulnerability.

A global health giant

Dr. Bill Foege, a hero who saved hundreds of millions of lives

Celebrating the life of a mentor and friend.

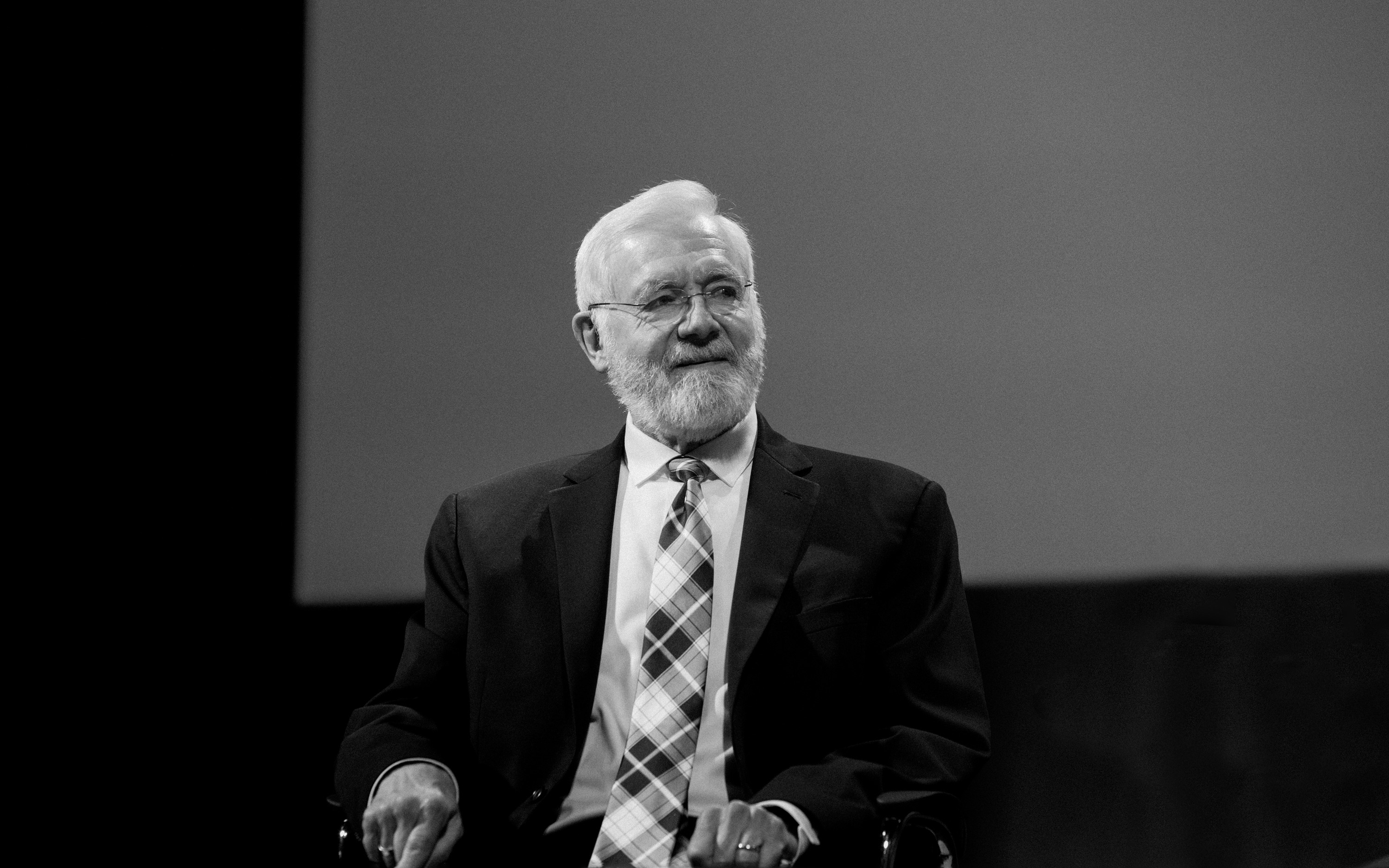

I’m greatly saddened to learn of the passing of Dr. Bill Foege. Bill was a towering figure in global health—a man who saved the lives of literally hundreds of millions of people. He was also a friend and mentor who gave me a deep grounding in the history of global health and inspired me with his conviction that much more could be done to alleviate suffering.

I first met Bill in 1999. At the time, I was interested in global health but didn’t know much about it. Soon after, we asked Bill to join the Gates Foundation as a senior advisor. In doing so, we used the oldest trick in the leadership handbook: get people who know more than you do to join your team.

It was obvious right away that Bill was a special person—not just because he was so accomplished but also because of his compassion for humanity. In that way, he reminded me of my dad.

Bill loved to send me books to help me educate myself about global health. In fact, right after we met for the first time, Bill followed up by sending me a list of 82 books and articles.

One of those books was Out of My Life and Thought, the autobiography of the global health pioneer Albert Schweitzer. “Fortunate are those who succeed in giving themselves genuinely and completely,” Schweitzer wrote in 1933. “[But] anyone who proposes to do good must not expect people to roll any stones out of his way, and must calmly accept his lot even if they roll a few more into it. Only force that in the face of obstacles becomes stronger can win.” That passage perfectly describes Bill and his willingness to do whatever it took to help the world’s poorest people.

Bill read Schweitzer’s book as a teenager growing up in rural eastern Washington, and it helped inspire him to dedicate his life to global health. When Bill attended medical school, the field of global health was sorely neglected. “At my fiftieth medical school class reunion, a classmate confessed that when I told him I wanted to go into global health, he said to himself, What a waste,” Bill wrote in his book The Fears of the Rich, the Needs of the Poor. And then Bill helped invigorate that neglected field.

He was best known for the strategy and leadership that helped the world eradicate smallpox, one of the most important victories in the history of public health. That success brought an end to a horrific disease that killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone. It also gave the world the confidence to try to eradicate polio, Guinea worm, measles, malaria, and other diseases.

Bill sometimes put his own life at risk to do his work. While fighting smallpox outbreaks during the Nigerian civil war, he was arrested and held in prison twice— “not a sought-after experience,” he wrote with his usual understatement. “But interestingly, my concern at the moment was for the time being lost for planning Monday’s [vaccination efforts].”

I had long known about his accomplishments as director of the Centers for Disease Control, but reading The Fears of the Rich, the Needs of the Poor gave me a deep understanding of the constant political and policy battles he had to fight during these years. “Reason was [often] brushed aside,” he wrote. “The power of science is often neutralized by the power of power.” Bill showed tremendous patience and moral courage in fighting for what he believed in.

When I first met Bill, I was also blown away by what he had done to expand vaccination for the world’s poorest children. He was instrumental in launching the Task Force for Child Survival, which quadrupled the percentage of children around the world who receive basic vaccinations. He also used his positions at the task force and as director of the Carter Center to help deliver a miracle drug called Mectizan to tens of millions of people a year suffering from a debilitating disease called onchocerciasis. Very few other people could have brought together such a diverse coalition of partners—including African health ministers, nonprofits, churches, and a major pharmaceutical company. Bill told that story in an essay that he let me share on Gates Notes in 2014. It is an amazing piece of writing and gives you a sense of the kind of person he was.

I also want people to know how humble Bill was. One of my favorite examples comes from the final days of the push to eradicate smallpox, when he and his family decided to return to the U.S. from India. His boss at the time urged Bill to remain in India until he and his team could celebrate the world’s final case of smallpox. Bill told his boss, “If I remain in India, too much attention would be directed toward the external support that India received, and it is very important that recognition be given to the accomplishments of hundreds of thousands of Indians who really did the work.”

Late in life, Bill spoke openly about his own mortality. “I feel so enthusiastic every day about seeing the newest thing in science and health,” he told an interviewer. “The part that’s going to be hard about dying is not dying but not being able to see what’s happening next.” The legacy of Bill’s career is that many of the remarkable developments to come will have his imprint all over them.

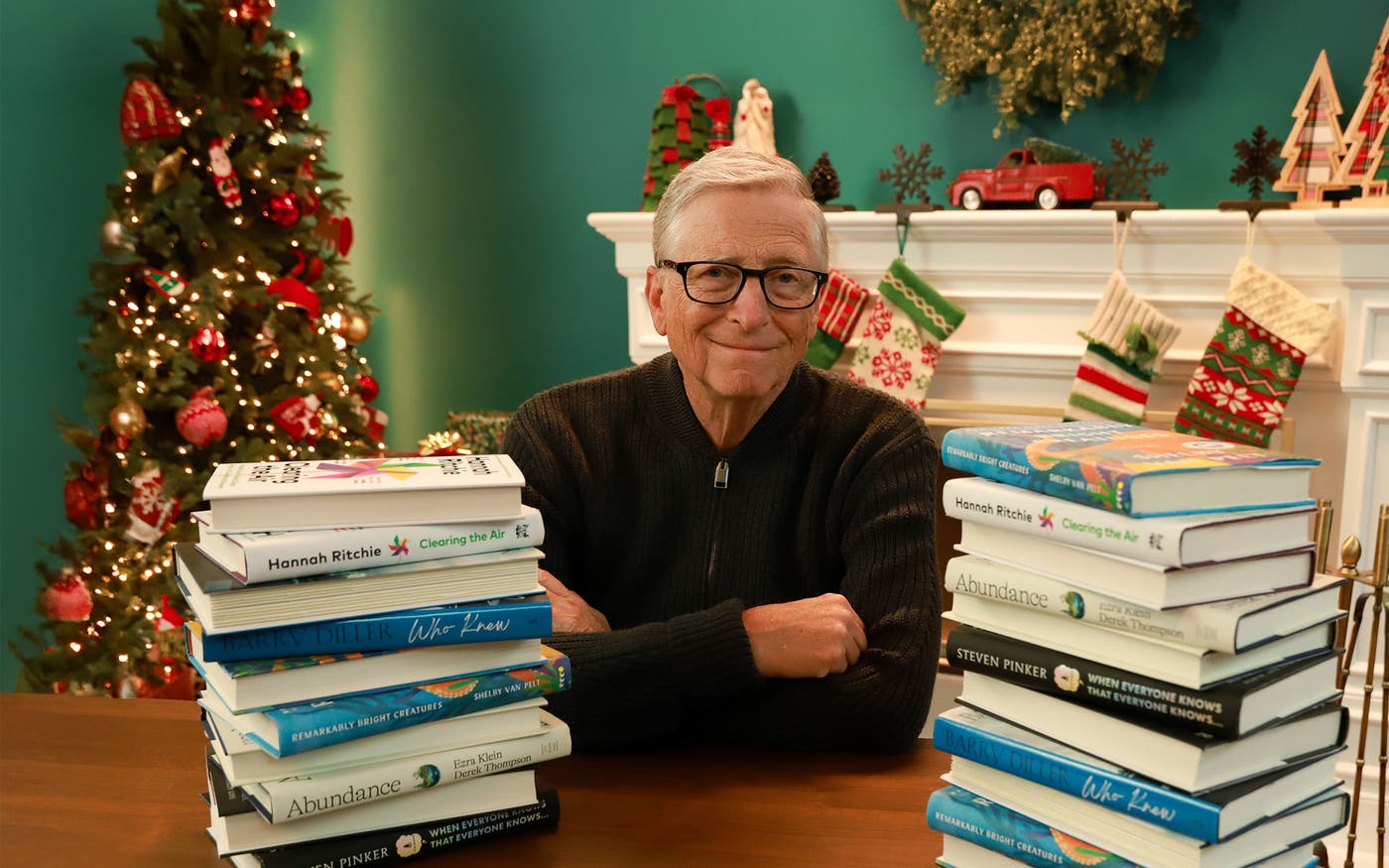

The Year Ahead

Optimism with footnotes

As we start 2026, I am thinking about how the year ahead will set us up for the decades to come.

I have always been an optimist. When I founded Microsoft, I believed a digital revolution powered by great software would make the world a better place. When I started the Gates Foundation, I saw an opportunity to save and improve millions of lives because critical areas like children’s health were getting so little money.

In both cases, the results exceeded my expectations. We are far better off than when I was born 70 years ago. I believe the world will keep improving—but it is harder to see that today than it has been in a long time.

Friends and colleagues often ask me how I stay optimistic in an era with so many challenges and so much polarization. My answer is this: I am still an optimist because I see what innovation accelerated by artificial intelligence will bring. But these days, my optimism comes with footnotes.

The thing I am most upset about is the fact that the world went backwards last year on a key metric of progress: the number of deaths of children under 5 years old. Over the last 25 years, those deaths went down faster than at any other point in history. But in 2025, they went up for the first time this century, from 4.6 million in 2024 to 4.8 million in 2025—an increase driven by less support from rich countries to poor countries. This trend will continue unless we make progress in restoring aid budgets.

The next five years will be difficult as we try to get back on track and work to scale up new lifesaving tools. Yet I remain optimistic about the long-term future. As hard as last year was, I don’t believe we will slide back into the Dark Ages. I believe that, within the next decade, we will not only get the world back on track but enter a new era of unprecedented progress.

The key will be, as always, innovation. Consider this: An HIV diagnosis used to be a death sentence. Today, thanks to revolutionary treatments, a person with HIV can expect to live almost as long as someone without the virus. By the 2040s, new innovations could virtually eliminate deaths from HIV/AIDS.

Budget cuts limit how many people benefit from lifesaving tools, as we saw to devastating effect last year. But nothing can erase the fact that for decades we didn’t know how to save people from HIV, and now we do. Breakthroughs are a bell that cannot be unrung. They ensure that we will never go back to the world in 2000 where over 10 million children died from preventable causes every year—and they form the core of my optimism about where the world is headed.

But as I mentioned, there are footnotes to my optimism. Although the innovation pipeline sets us up for long-term success, the trajectory of progress hinges on how the world addresses three key questions.

1.

Will a world that is getting richer increase its generosity toward those in need?

The “golden rule” precept is more important now than ever with the record disparities in wealth. This idea of treating others as you wish to be treated does not just apply to rich countries giving aid. It must also include philanthropy from the wealthy to help those in need—both domestically and globally—which should grow rapidly in a world with a record number of billionaires and even centibillionaires.

Through the Giving Pledge, I get to work with a number of incredible philanthropists who set a great example by giving away substantial portions of their wealth in smart ways. However, more needs to be done to encourage higher levels of generosity from the rich and to show how fulfilling and impactful it can be.

Turning to aid budgets for poor countries, I am worried about one number: If funding for health decreases by 20 percent, 12 million more children could die by 2045. I know cuts won’t be reversed overnight, even though aid represented less than 1 percent of GDP even in the most generous countries. But it is critical that we restore some of the funding. The foundation’s Goalkeepers report lays out what is at risk and how the world can best spend the aid it gives.

I will spend much of my year working with partners to advocate for increased funding for the health of the world’s children. I plan to engage with a number of communities, including health care workers, religious groups, and members of diaspora communities to help make this case.

2.

Will the world prioritize scaling innovations that improve equality?

Some problems require doing far more than just letting market incentives take their course.

The first critical area is climate change. Without a large global carbon tax (which is, unfortunately, politically unachievable), market forces do not properly incentivize the creation of technologies to reduce climate-related emissions.

Yet only by replacing all emitting activities with cheaper alternatives will we stop the temperature increase. This is why I started Breakthrough Energy 10 years ago and why I will continue to put billions into innovation.

The world has made meaningful progress in the last decade, cutting projected emissions by more than 40 percent. But we still have a lot of innovation and scaling up to do in tough areas like industrial emissions and aviation. Government policies in rich countries are still critical because unless innovations reach scale, the costs won’t come down and we won’t achieve the impact we need.

If we don’t limit climate change, it will join poverty and infectious disease in causing enormous suffering, especially for the world’s poorest people. Since even in the best case the temperature will continue to go up, we also need to innovate to minimize the negative impacts.

This is called climate adaptation, and a critical example is helping farmers in poor countries with better seeds and better advice so they can grow more even in the face of climate change. Using AI, we will soon be able to provide poor farmers with better advice about weather, prices, crop diseases, and soil than even the richest farmers get today. The foundation has committed $1.4 billion to supporting farmers on the frontlines of extreme weather.

I will be investing and giving more than ever to climate work in the years ahead while also continuing to give more to children’s health, the foundation’s top priority. The need to ensure money is spent on the most important priorities was the topic of a memo I wrote in the fall.

A second critical area where the world must focus on innovation-driven equality is health care. Concerns about healthcare costs and quality are higher than ever in all countries.

In theory, people should feel optimistic about the state of health care with the incredible pipeline of innovations. For example, a recent breakthrough in diagnosing Alzheimer’s will revolutionize how we test for—and ultimately prevent—this disease, saving billions of dollars in costs. (Funding Alzheimer’s research is a particular focus for me.) There’s similar progress on obesity and cancer, as well as on problems in developing countries like malaria, TB, and malnutrition.

Despite so much progress, however, the cost and complexity of the system means very few people are satisfied with their care. I believe we can improve health care dramatically in all countries by using AI not only to accelerate the development of innovations but directly in the delivery of health care.

Like many of you, I already use AI to better understand my own health. Just imagine what will be possible as it improves and becomes available for every patient and provider. Always-available, high-quality medical advice will improve medicine by every measure.

We aren’t quite there yet—developers still have work to do on reliability and how we connect the AI to doctors and nurses so they are empowered to check and override the system. But I’m optimistic we will soon begin to scale access globally. I am following this work so the Gates Foundation and partners can make sure this capability is available in the countries that need it most—where there aren’t enough medical personnel—at the same time it is available elsewhere. We are already working on pilots and making sure that even relatively uncommon African languages are fully supported.

Governments will have to play a central role in leading the implementation of AI into their health systems. This is another case where the market alone won’t and can’t provide the solution.

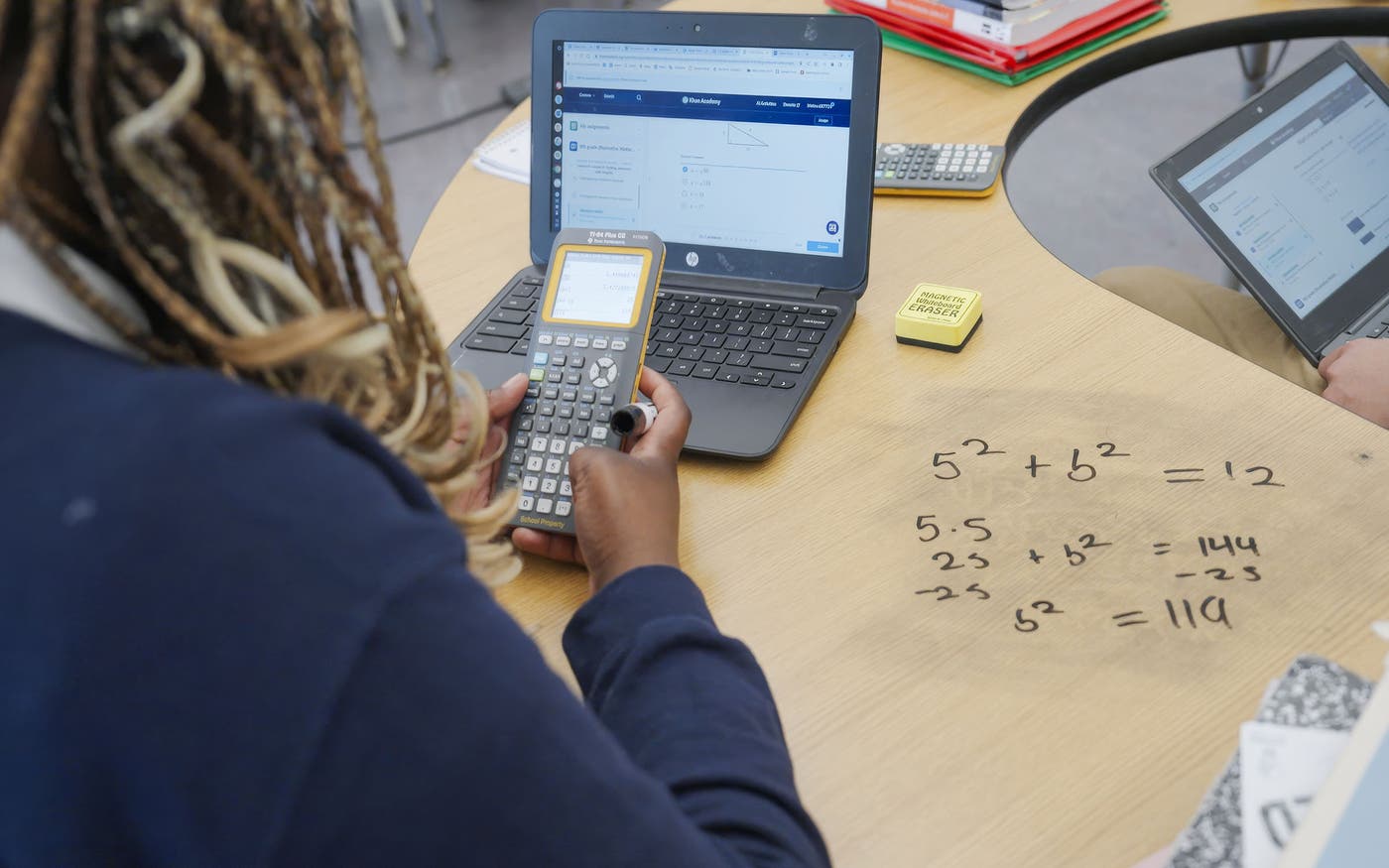

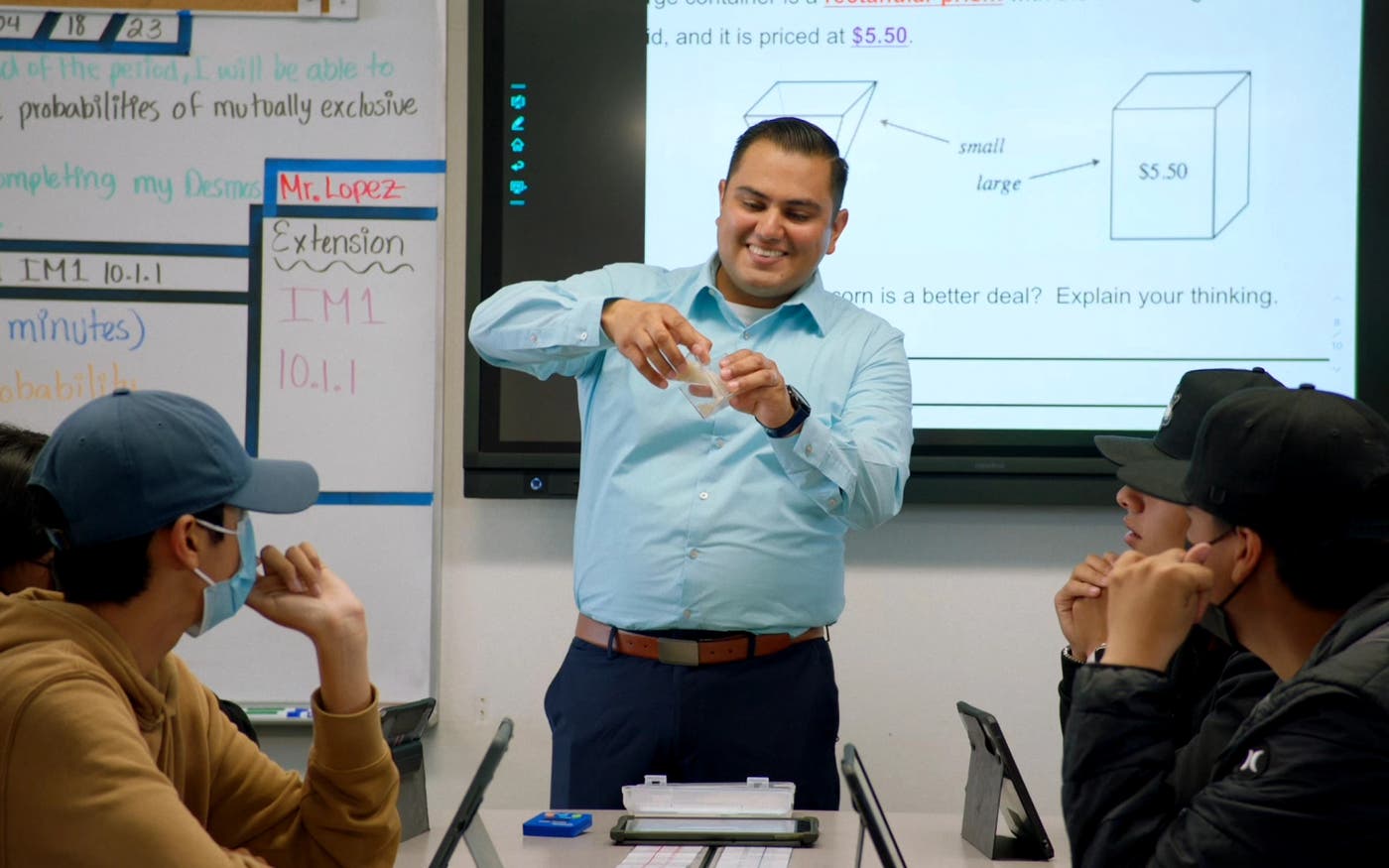

A third and final area I will mention briefly is education. AI gives us a chance for the kind of personalized learning to keep students motivated that we have dreamed of in the past. This is now a focus of the Gates Foundation’s spending on education, and I am hopeful it will be empowering to both teachers and students. I’ve seen this firsthand in New Jersey, and it will be game changing as we scale it for the world.

All three of these areas—climate, health, and education—can improve rapidly with the right government focus. This year I will spend a lot of time meeting with pioneers all over the world to see which countries are doing the best work so we can spread best practices.

3.

Will we minimize negative disruptions caused by AI as it accelerates?

Of all the things humans have ever created, AI will change society the most. It will help solve many of our current problems while also bringing new challenges very different from past innovations.

When people in the AI space predict that AGI or fully humanoid robots will come soon and then those deadlines are missed, it creates the impression that these things will never happen. However, there is no upper limit on how intelligent AIs will get or on how good robots will get, and I believe the advances will not plateau before exceeding human levels.

The two big challenges in the next decade are use of AI by bad actors and disruption to the job market. Both are real risks that we need to do a better job managing. We’ll need to be deliberate about how this technology is developed, governed, and deployed.

In 2015, I gave a TED talk warning that the world was not ready to handle a pandemic. If we had prepared properly for the Covid pandemic, the amount of human suffering would have been dramatically less. Today, an even greater risk than a naturally caused pandemic is that a non-government group will use open source AI tools to design a bioterrorism weapon.

The second challenge is job market disruption. AI capabilities will allow us to make far more goods and services with less labor. In a mathematical sense, we should be able to allocate these new capabilities in ways that benefit everyone. As AI delivers on its potential, we could reduce the work week or even decide there are some areas we don’t want to use AI in.

The effects of this disruption are hard to model. Sometimes, when a game-changing technology improves rapidly, it drives more demand at lower cost and, by making the world richer, increases demand in other areas. For example, AI makes software developers at least twice as efficient, which makes coding cheaper while also creating demand elasticity for code. (Computing is a good historical example where lower costs actually caused the overall market to grow.)

Even with this complexity, the rate of improvement is already starting to be enough to disrupt job demand in areas like software development. Other areas like warehouse work or phone support are not quite there yet, but once the AIs become more capable, the job disruption will be more immediate.

We’re already starting to see the impact of AI on the job market, and I think this impact will grow over the next five years. Even if the transition takes longer than I expect, we should use 2026 to prepare ourselves for these changes—including which policies will best help spread the wealth and deal with the important role jobs play in our society. Different political parties will likely suggest different approaches.

By including these footnotes, particularly the last one, some readers may find my continued optimism even more surprising. But as we start 2026, I remain optimistic about the days ahead because of two core human capabilities.

The first is our ability to anticipate problems and prepare for them, and therefore ensure that our new discoveries make all of us better off. The second is our capacity to care about each other. Throughout history, you can always find stories of people tending not just to themselves or their clan or their country but to the greater good.

Those two qualities—foresight and care—are what give me hope as the year begins. As long as we keep exercising those abilities, I believe the years ahead can be ones of real progress.

The doctor can see you now

Expanding access to health care through AI

Today’s AI can transform health care systems and support health care workers the world over.

A core principle underlying the Gates Foundation’s work is closing the innovation gap between rich countries and everyone else. People in poorer parts of the world shouldn’t have to wait decades for new technologies to reach them. That’s why we've worked for 25 years to accelerate access to life-saving medicines and vaccines in low- and middle-income countries.

It's also why, today, the Gates Foundation and OpenAI are announcing an initiative called Horizon1000 to support several countries in Africa, starting in Rwanda, as they apply AI technology to improve their health care systems.

Over the next few years, we will collaborate with leaders in African countries as they pioneer the deployment of AI in health. Together, the Gates Foundation and OpenAI are committing $50 million in funding, technology, and technical support to back their work. The goal is to reach 1,000 primary healthcare clinics and their surrounding communities by 2028.

Today’s AI can help save lives

A few years ago, I wrote that the rise of artificial intelligence would mark a technological revolution as far-reaching for humanity as microprocessors, PCs, mobile phones, and the Internet. Everything I’ve seen since then confirms my view that we are on the cusp of a breathtaking global transformation.

All over the world, AI, in the form of LLMs and machine learning models, are improving far more quickly than I first anticipated. From science to education to customer service and more, AI tools are reshaping every facet of our lives.

I spend a lot of time thinking about how AI can help us address fundamental challenges like poverty, hunger, and disease. One issue that I keep coming back to is making great health care accessible to all—and that’s why we’re partnering with OpenAI and African leaders and innovators on Horizon1000.

Not enough doctors in the house

We have seen amazing successes in global health over the past 25 years: child mortality has been cut in half, and there are now real pathways to eliminating or controlling deadly diseases like polio, malaria, TB, and HIV. But one stubborn problem that keeps slowing progress is the desperate shortage of health care workers in poorer parts of the world.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, which suffers from the world’s highest child mortality rate, there is a shortfall of nearly 6 million health care workers, a gap so large that even the most aggressive hiring and training efforts can’t close it in the foreseeable future.

These huge shortages put health care workers in these countries in an impossible situation. They’re forced to triage too many patients with too little administrative support, modern technology, and up-to-date clinical guidance. Partly as a result, the WHO estimates that low-quality care is a contributing factor in 6 to 8 million deaths in low- and middle-income countries every year, and that’s not even counting the millions who die because they aren’t able to access health care at all.

Rwanda leads the way

Today’s AI can help save those lives by reaching many more people with much higher-quality care.

Rwanda currently has only one health care worker per 1,000 people, far below the WHO recommendation of about four per 1,000. It would take 180 years for that gap to close at the current pace of progress. So, as part of the 4x4 reform initiative, Minister of Health Dr. Sabin Nsanzimana recently announced the launch of an AI-powered Health Intelligence Center in Kigali to help ensure limited health care resources are being used as wisely as possible.

As part of the Horizon1000 initiative, we aim to accelerate the adoption of AI tools across primary care clinics, within communities, and in people’s homes. These AI tools will support health workers, not replace them.

On the horizon

Minister Nsanzimana has called AI the third major discovery to transform medicine, after vaccines and antibiotics, and I agree with his point of view.

If you live in a wealthier country and have seen a doctor recently, you may have already seen how AI is making life easier for health care workers. Instead of taking notes constantly, they can now spend more time talking directly to you about your health, while AI transcribes and summarizes the visit. Afterwards, AI can handle much of the onerous paperwork, so doctors and nurses can focus on the next patient.

In poorer countries with enormous health worker shortages and lack of health systems infrastructure, AI can be a gamechanger in expanding access to quality care. I believe this partnership with OpenAI, governments, innovators, and health workers in sub-Saharan Africa is a step towards the type of AI we need more of: systems that help people all over the world to solve generational challenges that they simply didn’t know how to address before. I invite others working on AI to think about how we can put these massively powerful tools to the best use.

This announcement is a great example of why I remain optimistic about the improvements we can make. I’m looking forward to seeing health workers using some of these AI solutions in action when I visit Africa, and I plan to continue focusing on ways AI technology can help billions of people in low- and middle-income countries meet their most important needs.

My look back

The breakthrough that transformed the Gates Foundation

This is the story of how better data helped us cut child mortality in half.

We started the Gates Foundation 25 years ago to save and improve children’s lives. But no one can solve a problem they don’t fully understand. And back in 2000, the world’s understanding of childhood mortality was occasionally inaccurate, often imprecise, and almost always incomplete.

That’s why I believe the breakthrough that transformed our foundation in the two-and-a-half decades since wasn’t a single vaccine or treatment—it was a revolution in the world’s understanding of childhood mortality. Through advances in how researchers collect and analyze global health data, we now know much more about what kills children, where these deaths occur, and why some kids are more vulnerable than others. By putting those insights to work, we’ve been able to save lives.

The first challenge was knowing exactly what was killing children.

Reading the 1993 World Development Report opened my eyes to the scale of the problem: Around 12 million children under the age of five were dying every year, with a staggering disparity between rich and poor countries. But the available data was fragmented and inconsistent. That made it difficult to understand trends or allocate resources effectively.

So the foundation helped create the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, to give a permanent home to the Global Burden of Disease study—originally developed in the 1990s by researchers at Harvard University and the World Health Organization. We wanted to expand it from a static snapshot of the problem into a regularly updated tool that tracked how diseases impact people around the world. That gave us something the world never had before: a comprehensive—and current—picture of child mortality across every country.

Measuring symptom-based causes of children’s deaths was an important step. But broad disease categories like “diarrhea” or “respiratory infection” didn’t give us enough information to act on. We needed to know which specific pathogens were responsible for the most common and fatal cases. So the Gates Foundation funded two landmark studies to find out.

In 2013, the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, or GEMS, found that rotavirus was causing 20 percent of lethal diarrhea cases in kids. At the time, diarrhea was the second-leading infectious killer of children. While oral rehydration therapy had already helped bring down deaths over previous decades, GEMS helped fast-track the rollout of a more targeted tool—a new rotavirus vaccine—in the hardest-hit countries, in close partnership with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

A year later, the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study, or PERCH, revealed that respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, was a much more common cause of severe pneumonia—the leading infectious killer of kids around the world—than previously understood. (And not just in low- and middle-income countries, where 97 percent of RSV deaths occur, but in higher-income ones too, where the virus still fills pediatric hospital wards each winter.) That prompted us to expand our investments in RSV prevention, which led to the approval of the first maternal vaccines for RSV in 2023.

But understanding what causes childhood mortality wasn’t enough on its own, because deaths aren’t distributed evenly across countries—or even within them. That’s why our second challenge was to figure out where exactly children were dying.

At the time, most health data was collected at national or regional levels. That masked major differences in disease burden from one community to the next—and made it harder to target interventions effectively.

To solve this second challenge, the foundation invested in new approaches to health mapping that combined satellite imagery, GIS technology, GPS data, and local health surveys. These maps gave Ministries of Health and implementing partners unprecedented, anonymized detail about disease patterns and population distribution, down to individual neighborhoods, that transformed how and where public health resources are deployed—while still preserving the privacy of the individual children and families in these places.

In Pakistan—one of just two countries where wild polio remains endemic—advanced mapping tools have helped vaccination teams reach and protect kids in settlements that weren’t on any official maps. Across sub-Saharan Africa, better geographic data has transformed the fight against malaria by revealing that transmission often clusters in small, hyper-local pockets. Through the Malaria Atlas Project, countries like Nigeria can now track those patterns more precisely—and then get bed nets, testing, and treatment where they’ll have the greatest impact.

With better knowledge of what was killing children, and where, one more fundamental question remained: Why might one child die from a disease while another—who lives in the same place, faces the same risks, and gets the same treatment—survives? This was our third big challenge.

In theory, traditional autopsies would provide the answer. But in the places where most childhood deaths still occur, these invasive procedures are often impossible to perform—too costly, and sometimes opposed for religious, cultural, or personal reasons.

So in 2015, the foundation launched the Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance network, or CHAMPS, which now operates in nine countries across Africa and South Asia. Working with in-country partners, CHAMPS pioneered a new autopsy alternative—using minimally invasive tissue sampling—that can determine causes of death quickly and accurately while respecting local customs and beliefs.

Through CHAMPS, we discovered that childhood deaths rarely have a single cause. Instead, kids often have multiple conditions at the same time, with malnutrition frequently leaving them much more vulnerable to a whole host of infections. (While it rarely shows up on death certificates, it’s an underlying cause of death in nearly half of all child mortality cases.) That finding helped solidify nutrition as a core focus of the foundation’s global health work—and the research, innovation, and product development we invest in. On the ground, we’re supporting partners as they integrate nutrition screening into routine care and train healthcare workers to manage multiple risks at once.

CHAMPS also demonstrated that inadequate prenatal care is responsible for a majority of stillbirths, newborn deaths, and maternal deaths, prompting us to further expand access to maternal health services—like prenatal vitamins and AI-enabled ultrasounds—in the communities where we work.

But the biggest takeaway from CHAMPS is also the most hopeful—and a reminder of why we started the Gates Foundation in the first place: So many childhood deaths could be prevented with existing interventions. We just need to ensure they reach the right children at the right time.

Twenty-five years in, our work on child mortality is far from complete. Still, the impact of what we have learned has been enormous

The Global Burden of Disease, GEMS, and PERCH studies helped shift global priorities by showing the world what was really killing kids—and where new vaccines and treatments could make the biggest difference. Better geospatial tools have empowered countries to pinpoint disease hotspots, find previously unmapped settlements, and distribute life-saving resources where they’re needed most. And CHAMPS is giving governments better data on why children are dying—data that’s now shaping policies, improving reporting, and guiding more effective care.

Most importantly, even as the number of children born every year has gone up, the number of overall childhood deaths has fallen by more than half—from 11.3 million in 1990 to 4.5 million in 2022. Playing a part in making that happen is the best job I’ve ever had, and the most meaningful work I’ve ever done.

At the Gates Foundation, we used to say we could cut child mortality in half again by 2040. The truth, though, is that goal feels further out of reach now—not because the science has stalled, but because support for global health has. The progress we’ve been part of was only possible because governments around the world, including here in the U.S., made long-term commitments to saving lives and followed through. That kind of leadership gave millions of children who would have died a chance at life—and made life better for millions more.

The last 25 years have shown us what’s possible. The next 25 will depend on whether the world keeps showing up for the children who need it most.

My look ahead

What it takes to take a breath

New tools can help millions more newborns—and their mothers—survive.

In a rural health clinic, a baby tries to take her first breath.

But her lungs aren’t ready. Because she was born too early, they haven’t developed the slick, soap-like substance that keeps her air sacs from collapsing. Without that substance—called lung surfactant—breathing becomes a desperate, exhausting act.

She’s suffering from respiratory distress syndrome, or RDS, a life-threatening condition that appears within hours of birth in premature babies. Unless she gets treatment, her oxygen levels will plummet and her organs will begin to shut down. In one study from India, every baby born with RDS outside of a hospital setting died. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, RDS is responsible for almost half of all neonatal deaths.

At hospitals in higher-income countries, there’s a way to save her: a liquid form of organically-derived surfactant delivered directly into the lungs. But the procedure requires a highly-trained specialist to guide a breathing tube down the newborn’s windpipe—avoiding the stomach and placing it just right—at a cost of up to $20,000. In many parts of the world, that kind of care simply doesn’t exist.

But what if any healthcare worker anywhere in the world could simply hold a small nebulizer to the baby's face and deliver surfactant as an easy-to-administer inhalant?

This breakthrough—a synthetic surfactant that’s stable enough to be delivered through a nebulizer—is still in development, drive in part by Gates Foundation-supported research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, and The Lundquist Institute. But its promise is extraordinary: an RDS treatment that costs less to make, doesn’t require a specialist to administer, and eliminates the need for intubation.

In other words, a therapy currently limited to the most advanced hospitals could become accessible in rural clinics and community settings around the world. Even in places with top-tier care, it could make treatment gentler, faster, and easier to deliver. In the United States—where RDS still affects 24,000 newborns a year—it could reduce the risks that come with intubating babies who might weigh only two or three pounds.

It’s the kind of innovation that could help solve one of the most persistent problems in global health: delivering intensive care without an intensive care unit, and helping millions more babies survive their first, most fragile moments.

Since 1990, the mortality rate for children under five has been cut by more than half—an amazing mark of global progress. But another statistic hasn’t fallen as fast: the number of babies who die in their first month of life.

Each year, 2.3 million newborns don’t survive past their first 28 days. And the day a baby is born is the most dangerous day of their life. The single biggest cause of these deaths is prematurity. Nearly 900,000 babies a year die from complications related to being born too soon, including infection, underdeveloped organs, and RDS.

Lower cost, easier-to-deliver surfactant is one way to give newborns a fighting chance, but it’s not the only way. Around the world, simple, affordable interventions already exist to identify at-risk pregnancies earlier, prevent more preterm births, and ensure a healthy birthing experience for mothers. Not only are these tools designed to work in the hardest-to-reach places—many of them start working even before a baby takes that first breath.

One of these innovations is a new type of ultrasound that’s changing who can catch the risks of preterm birth—and where.

Around the world, two thirds of women never get an ultrasound screening during pregnancy. Traditional machines are bulky and expensive, with specialized training required to operate them and interpret their results. In places where medical resources are already stretched thin, these types of ultrasounds are rarely an option.

But now, we have ultrasound devices about the size of a phone that can be operated by a nurse or midwife—no on-site specialist required. They weigh less than a pound. They process scans instantly. Their AI interface automatically detects high-risk conditions, like a shortened cervix or signs of early labor, so patients are referred for further care. And they have built-in telehealth functions to share images with remote specialists when needed.

By finding and flagging risks early, these AI-enabled ultrasounds are giving healthcare workers more time to act. In some cases, that means transferring the mother to a higher-level facility. In others, it means providing her with antenatal steroids—an inexpensive, underused treatment that speeds up fetal lung development—and, when needed, medications that delay labor just long enough for those steroids to take effect.

Early warning is essential, but we can save even more lives by going further upstream, starting with the health of pregnant women themselves.

In many low-income countries, undernutrition isn’t an exception. It’s the norm. And the intense demands of pregnancy make nutritional deficiencies even worse—putting mothers at increased risk of complications or death in childbirth, and raising the odds of early labor, low birth weight, and developmental delays for their babies.

But there’s a surprisingly simple fix: a daily supplement called MMS, or multiple-micronutrient supplementation, developed by the United Nations. It contains 15 essential vitamins and minerals for pregnancy—like zinc to reduce the risk of early labor, folic acid to help prevent birth defects, iron and vitamin D for healthy birth weight, and iodine for brain development. For an entire pregnancy, it costs just $2.60.

If MMS became the standard prenatal supplement in every low- and middle-income country, it could save nearly half a million newborn lives each year—and prevent serious complications in 25 million births by 2040.

The innovations above focus on treating, detecting, and preventing premature birth, a huge threat to newborn survival. But one of the most powerful ways to protect babies, preterm or full-term, is by ensuring their mothers stay healthy through pregnancy and childbirth.

When a woman dies during delivery, her baby is 46 times more likely to die in that first month of life. That’s why any serious effort to tackle infant mortality must also address postpartum hemorrhage—which tragically kills 70,000 women a year and is the leading cause of maternal mortality. Fortunately, two innovations are already helping healthcare workers catch and treat it before it becomes fatal.

The first is a calibrated drape—a simple plastic sheet placed under a woman during delivery that collects blood and shows, through printed measurement lines, exactly how much she’s losing. It gives healthcare workers a fast, accurate way to spot dangerous bleeding before it becomes life-threatening. The second is a one-time, 15-minute iron infusion during pregnancy that treats severe anemia—so if a woman does hemorrhage during childbirth, she’s less likely to experience catastrophic blood loss and more likely to survive.

Neither of these tools is complicated or expensive. But in combination, they can make a life-or-death difference for mothers and the babies who depend on them.

Taken together, these innovations form a chain of survival. They help mothers stay healthy through pregnancy. They detect problems before they become emergencies. They give fragile newborns a fighting chance. And they make it possible for families to celebrate a baby’s birth rather than mourning a loss.

Some of these tools are already saving lives. Others are on the verge of doing so. But their impact will be limited unless we prioritize and fund their delivery, not just their development. The world needs to make sure these innovations don’t get stuck in labs or warehouses—so they can reach the mothers and babies who need them most.

Just the facts

Health aid saves lives. Don’t cut it.

Here’s the proof I’m showing Congress.

I’ve been working in global health for 25 years—that’s as long as I was the CEO of Microsoft. At this point, I know as much about improving health in poor countries as I do about software.

I’ve spent a quarter-century building teams of experts at the Gates Foundation and visiting low-income countries to see the work. I’ve funded studies about the effectiveness of health aid and pored over the results. I’ve met people who were on the brink of dying of AIDS until American-funded medicines brought them back. And I’ve met heroic health workers and government leaders who made the best possible use of this aid: They saved lives.

The more I’ve learned, the more committed I’ve become. I believe so strongly in the value of global health that I’m dedicating the rest of my life to it, as well as most of the $200 billion the foundation will give away over the next 20 years.

People in global health argue about a lot of things, but here’s one thing everyone agrees on: Health aid saves lives. It has helped cut the number of children who die each year by more than half since 2000. The number used to be more than 9 million a year; now it’s fewer than 5 million. That’s incontrovertible.

So when the United States and other governments suddenly cut their aid budgets the way they've been doing, I know for a fact that more children will die. We’re already seeing the tragic impact of reductions in aid, and we know the number of deaths will continue to rise.

A study in the Lancet looked at the cumulative impact of reductions in American aid. It found that, by 2040, 8 million more children will die before their fifth birthday. To give some context for 8 million: That's how many children live in California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio combined.

I’ve submitted written testimony on this topic, which you can read below, for the Senate Appropriations Committee hearing occurring later today. In it, I discuss what’s already happened and what needs to happen next.

Testimony to the United States Senate Committee on Appropriations

June 25, 2025

Over the past 25 years—the same span of time I spent leading Microsoft—I have immersed myself in global health: building knowledge, deepening expertise, and working to save lives from deadly diseases and preventable causes. During that time, I have built teams of world-class scientists and public health experts at the Gates Foundation, studied health systems across continents, and worked in close partnership with national and local leaders to strengthen the delivery of lifesaving care. I have visited hundreds of clinics, listened to frontline health workers, and spoken with people who rely on these programs. Earlier this month, I traveled to Ethiopia and Nigeria, where I witnessed firsthand the impact that recent disruptions to U.S. global health funding are having on lives and communities.

Global health aid saves lives. And when that aid is withdrawn—abruptly and without a plan—lives are lost.

Yet, in recent months, some have questioned whether the foreign assistance pause has caused harm. Concerns about the human impact of these disruptions have been dismissed as overstated. Some people have even claimed that no one is dying as a result.

I wish that were true. But it is not.

It is important to note that while this hearing is about the Trump Administration’s $9 billion recission package, what is really at stake is tens of billions of dollars in critical aid and health research that has been frozen by DOGE with complete disregard for the Congress and its Constitutional power of the purse.

In the early weeks of implementing the foreign aid freeze, DOGE directives resulted in the dismissal of nearly all United States Agency for International Development (USAID) staff and many personnel at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some funding was later restored to allow for the continuation of what has been categorized as "lifesaving" programs. However, to date that designation has been applied narrowly and with limited transparency, in an inconsistent manner, often prioritizing emergency interventions when a patient is already in critical condition over essential preventative or supportive care.

For example, providing a child with a preventive antimalarial treatment, ensuring access to nutrition so that HIV/AIDS medications can be properly administered, testing pregnant women for HIV to see if they are eligible for treatment to prevent transmission to their children or identifying and treating tuberculosis cases early have not consistently qualified for exemption. As a result, many of the programs delivering these services have been suspended, delayed, or scaled back.

Recent reporting from the New York Times has shed light on the devastating human cost of the abrupt aid cuts. One especially tragic example is Peter Donde, a 10-year-old orphan in South Sudan, born with HIV, who died in February after losing his access to life-saving medication when USAID operations were suspended. His story is one of many.

During my recent visit to Nigeria, I met with leaders from local nonprofit organizations previously funded by the United States. One group shared the remarkable progress they had made in tuberculosis detection and treatment. In just a few years, case identification increased from 25 percent to 80 percent, a critical step toward breaking transmission and reducing the overall disease burden. That progress has now stalled. The grants that enabled this work were tied to USAID staff who have been dismissed, and with their departure, the funding ended, and the work stopped.

The broader effects of these sudden shifts are difficult to overstate. For example, funding for polio eradication has been preserved in the State Department budget but cut from the CDC—even though the two agencies collaborate closely on the program. This type of fragmented decision-making has left implementing organizations uncertain about staffing and operations. Many no longer feel confident that promised U.S. funds will materialize, even when awards have been announced. In some cases, staff continue to work without pay. Some organizations are approaching insolvency.

Meanwhile, in warehouses across the globe, food aid and medical supplies sourced from American producers are sitting idle—spoiling or approaching expiration—because the systems that once distributed them have been disrupted. Clinics are closing. Health workers are being laid off. HIV/AIDS patients are missing critical doses of medication. Malaria prevention campaigns, including bed net distributions and indoor spraying, have been delayed or canceled, leaving hundreds of millions of people unprotected at the peak of transmission season.

Efforts to track data that would illustrate the severity of this worsening crisis have also been severely compromised. Many of the people responsible for collecting and reporting health information—health workers, statisticians, and program managers—have been laid off or placed on leave. The systems that once monitored health outcomes are shutting down, and the offices where that data was once analyzed now sit empty. As a result, the true scope of the harm is becoming harder to measure, just as the need for information is most urgent.

The situation we face is not about political ideology, and it is not a debate over fiscal responsibility. U.S. government spending on global health accounts for just 0.2 percent of the federal budget. Shutting down USAID did nothing to reduce the deficit. In fact, the deficit has grown in the months since.

Furthermore, many of the allegations regarding waste, fraud, and abuse have proven to be unsubstantiated. For example, the widely circulated claim that USAID sent millions of dollars’ worth of condoms to the Gaza Strip is inaccurate. In fact, the Wall Street Journal reported that the program allocated approximately $27,000 for condoms as part of an HIV transmission prevention initiative—not in the Middle East, but in Gaza Province, Mozambique.

What we are witnessing because of the rapid dismantling of America’s global health infrastructure is a preventable, human-caused humanitarian crisis—one that is growing more severe by the day. DOGE made a deadly mistake by cutting health aid and laying off so many people. But it is not too late to undo some of the damage.

A Record of Progress—and What is at Risk

Since 2000, child mortality worldwide has been cut in half. Deaths from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria have declined significantly. And we are on the verge of eradicating only the second human disease in history: polio. These are not abstract statistics; they represent tens of millions of lives saved. None of this progress would have been possible without consistent, bipartisan U.S. leadership and investment.

Over the past several decades, the United States has built one of its most strategic global assets: a respected and robust public health presence. This leadership is not just a humanitarian achievement—it is a core pillar of American soft power and security. For example, a Stanford study analyzing 258 global surveys across 45 countries found that U.S. health aid is strongly linked to improved public opinion of the United States. In countries and years where U.S. health aid was highest, the probability of people having a very favorable view of the United States was 19 percentage points higher. Other forms of aid—like military or governance—did not have the same effect. Another example is the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The rapid deployment of U.S. scientists, health workers, and CDC teams helped contain the virus before it could spread globally. Their presence allowed the U.S. to help shape the response strategy, speed up containment, and prevent a wider outbreak. Many African countries are facing the dual burden of rising debt and pressing health needs, forcing painful choices between repaying creditors, and protecting their citizens. Helping them navigate this challenge is not just the right thing to do—it is a strategic imperative. If the United States retreats, others will fill the gap, and not all of them will bring our values, our priorities, or our interests to the table. Preserving American global influence will require restoring the staff, systems, and resources that underpin it—before the damage becomes irreversible.

I understand the fiscal pressures facing Congress. I recognize the need to prioritize spending and to hold programs accountable for results. I also share the Trump Administration’s commitment to promoting efficiency and encouraging country-led solutions. But I believe those goals can—and must—be pursued while still protecting the programs that deliver the highest return on investment and the greatest impact on human lives.

The United States’ support for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) represent some of the smartest, most effective investments our country has ever made. These initiatives are proven, strategically aligned with American interests, and cost-effective on a scale few other government programs can match.

Together, Gavi and the Global Fund have helped save more than 82 million lives. Gavi has helped halve childhood deaths in the world’s poorest countries and returns an estimated $54 for every $1 invested. The Global Fund has contributed to a 61% reduction in deaths from HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. PEPFAR has saved over 26 million lives and helped millions of children be born HIV-free. GPEI has brought us closer than ever to the eradication of polio. Pulling back now would not only jeopardize these historic gains—it would invite a resurgence of preventable disease, deepen global instability, and undermine decades of bipartisan American leadership.

This is not a forever funding stream for the U.S. Government. These programs set out clear pathways for countries to “graduate” from aid, which many have already done. For example, nineteen countries, including Viet Nam and Indonesia, have successfully graduated from Gavi support and now fully finance their own immunization programs. Others—from Bangladesh to Cote d'Ivoire—are on track to do the same. This is how U.S. development policy should work: catalytic, cost effective, and designed to help countries become self-reliant and drive their own progress. I agree that aid funding should have an end date, but not overnight. The most effective path to that end date is innovation. By investing in the development and delivery of new medical tools and treatments, we can drive down the cost of care, and in some cases, make diseases that were once a death sentence treatable, or even curable. Advances in therapies for chronic conditions like sickle cell disease, HIV, or certain types of cancers could transform lives and health systems. American innovation offers a sustainable exit strategy—one that reduces long-term costs, allows the United States to responsibly step back, and builds lasting trust and good will that far exceed the original investment.

Over the past 25 years, the Gates Foundation has invested nearly $16 billion in global health partnerships like Gavi, the Global Fund, and GPEI. We will continue to invest, through innovation, research, and close coordination with partners. But no private institution—or coalition of them—can replace the scale, reach, or authority of the U.S. government in delivering lifesaving impact at the global level.

The decisions made in the coming weeks will shape not only the lives saved in the near term—but the legacy of American leadership for generations to come.

Download a PDF of the testimony with appendices that include reflections from Gates Foundation staff in Africa on the impact of the U.S. aid cuts; analytical projections from respected organizations; and a selection of first-hand reporting from reputable news organizations and journalists.

The last mile

We’re closer than ever to eradicating polio

...And closer than ever to seeing a resurgence.

When most Americans think of polio, we probably picture President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In 1921, at age 39, he was paralyzed by the virus and never regained the use of his legs. His story helped turn polio into a national cause. But in many ways, his experience was an anomaly.

After all, polio is overwhelmingly a childhood disease, with the vast majority of cases affecting those younger than five. That was true when FDR fell ill, and it’s true today. The typical patient isn’t an adult with an already established political career—it’s a little kid, often a little kid in a low-income country, who might never get the chance to take his first steps.

That injustice is one big reason I've spent the past two decades working to eradicate polio. The other reason is that eradication is actually possible, realistic, and well within reach. This is a disease we can get rid of—not just control, but eliminate everywhere. That is a rarity in global health.

The world has already made extraordinary progress. Back in 1988, when Rotary International and the World Health Assembly set the goal of eradication, the virus was paralyzing more than 350,000 children each year across 125 countries. Since then, cases have dropped by 99.9 percent. The strains known as Type 2 and Type 3 wild poliovirus have been eradicated. The entire African continent is certified wild-polio free. Only two countries—Afghanistan and Pakistan—still have persistent transmission of Type 1 wild poliovirus.

Now we're closer than ever to total polio eradication. But the last mile is proving the hardest because viruses find ways to exploit any immunity gaps or weaknesses. Wherever vaccination rates slip—even briefly—they can resurface.

One of the biggest challenges comes from what are called variant outbreaks. In communities where immunization is low, the weakened virus used in the oral polio vaccine can circulate asymptomatically and rarely, over time, mutate enough to regain the ability to cause paralysis in unvaccinated children.

While most variant outbreaks happen in places with extremely low vaccination coverage, poor sanitation, and weaker health systems, no place is risk-free until the world is polio-free. In 2022, the United States confirmed its first paralytic polio case in nearly a decade, and the virus was detected in New York wastewater samples. In the time since, variant polioviruses have also been found in the U.K., Ukraine, Indonesia, and other countries.

The good news is that today’s tools are better than anything we had even five years ago, and they make every dollar spent on the cause go further than ever before. We have a new oral vaccine, nOPV2, that’s far less likely to mutate and lead to new variant outbreaks; nearly two billion doses have already been given worldwide. New regional labs in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda that test wastewater samples and sequence viruses have cut detection times by over 30 percent, which gives health workers a critical head start on outbreak response. And the surveillance network for polio is one of the most sophisticated ever built—also helping alert public health officials to outbreaks of cholera, measles, Ebola, and even COVID-19 at the height of that pandemic.

The Gates Foundation has been proud to support these advances as part of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, a coalition of the WHO, UNICEF, the CDC, Gavi, Rotary International, and dozens of countries’ governments. It’s one of the most successful collaborations in the history of global health.

But right now, GPEI is facing a $1.7 billion funding gap, with various long-term donor governments cutting back their support. Without the right resources, vaccination campaigns may have to be scaled back, surveillance sites will likely close, and the virus could spread globally.

In the century since FDR was paralyzed by the virus, American leadership and generosity have helped turn polio into a fight the whole world could win. From the March of Dimes, which funded research, to the development of the first vaccines, to support for eradication campaigns, U.S. commitment has been decisive.

The world is at the brink of ending this terrible disease, and the stakes of this moment couldn’t be higher. If we finish the job, we free up billions of dollars for other health priorities and—most importantly—protect generations of children from a virus that has paralyzed millions. If we back down from the fight, up to 200,000 children could be paralyzed each year within a decade.

We have the scientific tools and infrastructure needed to cross the finish line. And we have hundreds of thousands of committed vaccinators who are determined to get us there—who go door to door across deserts, jungles, floodplains, and war zones to make sure no child is missed. I've met them, I've heard their stories, and I've seen how determined they are to finish the job.

We should be too.

PrEP talk

From once a day to twice a year

Long-acting preventatives will save more lives from HIV/AIDS.

I’ve been working in global health for two and a half decades now, and the transformation in how we fight HIV/AIDS is one of the most remarkable achievements I’ve witnessed. (It’s second only to how vaccines have saved millions of children's lives.)

At the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, an HIV diagnosis was often a death sentence. But in the years since, so much has changed. Today, not only do we have anti-retroviral medications that allow people with HIV to live full, healthy lives with undetectable viral loads—meaning they can’t transmit the virus to others. We also have powerful preventative medications known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, that can reduce a person’s risk of contracting the virus by up to 99 percent when taken as prescribed. It’s an incredible feat of science: a pill that virtually prevents HIV contraction.

In theory, if we could get these tools to everyone who needs them and make sure they’re used correctly, we could stop HIV in its tracks. Because when people with the virus receive proper treatment, they can’t transmit it to others. And when people at risk take PrEP, they can’t contract it. In practice, however, getting these tools to people—and making sure they’re used correctly—is the hard part. Especially for PrEP.

That’s because current preventatives require people to take medication every single day. Miss a dose, and protection drops. It’s like trying to remember to lock your front door 365 times a year—if you mess up once, you’re vulnerable. For many people, the barriers stack up quickly. Some have to walk hours to reach a clinic. Others struggle to store medication safely or discreetly at home. And many face judgment and stigma for taking PrEP, especially young women in conservative communities. The very act of protecting yourself can lead to being shamed or ostracized.

That’s why I’m so excited about a new wave of innovations in HIV prevention. Scientists are in the process of developing several longer-lasting PrEP breakthroughs, each with distinct advantages that could help more people protect themselves on their own terms.

Lenacapavir, which requires only two doses per year through injection, could open HIV prevention up to people who can’t make frequent clinic visits. Cabotegravir, another injectable option that works for two months at a time, offers a more flexible dosing schedule than daily PrEP pills, too. Meanwhile, a monthly oral medication called MK-8572, still in the trial stage, could provide an alternative for people who prefer pills to injections. The Gates Foundation is even exploring ways to maintain a person’s protection for six months or longer. And researchers are working on promising PrEP options that include contraception, which would be particularly valuable for women who need both types of protection.

To understand how these options work in real life, and not just in labs, our foundation has supported implementation studies in South Africa, Malawi, and elsewhere. Unlike traditional clinical trials that test safety and efficacy in highly controlled settings, these studies examine how medications fit into people’s lives and work in everyday circumstances—looking at ease of use, cultural acceptance, and other practical challenges. This real-world understanding is crucial for successful adoption.

Some people ask me if these new preventative tools mean the Gates Foundation has given up on finding an HIV vaccine. Not at all. In fact, these advances push us to aim even higher in our research for a vaccine that could prevent HIV for a lifetime—and not just a few months at a time. Our goal is to create multiple layers of protection, much like modern cars have seatbelts, airbags, and even collision-warning sensors. Different tools work better for different people in different ways, and we need every tool we can get.

But even the most brilliant innovations make no difference unless they reach the people who need them most. This is where partnerships become crucial. Through grants to research institutions around the world, the foundation is working to lower manufacturing costs for HIV drugs so they’re accessible to everyone, everywhere. Then there are organizations like the Global Fund and PEPFAR, which have been instrumental in turning scientific advances into real-world impact.

The Global Fund—which needs to raise significant new resources next year to continue its work—currently helps more than 24 million people access HIV prevention and treatment. And PEPFAR has saved 25 million lives since its inception in 2003—a powerful example of how American leadership can build tremendous goodwill while transforming the world. Motivated by the belief that no person should die of HIV/AIDS when lifesaving medications are available, President George W. Bush created PEPFAR with strong bipartisan backing and it continues to serve as a lifeline to millions of people.

We're at a pivotal moment in this fight. Twenty years ago, many believed it would be impossible to deliver HIV treatment at scale in Africa’s poorest regions. Since then, we’ve made fantastic progress. Science has shown us promising paths forward—for better prevention options, easier treatment regimens, and, maybe one day, an effective vaccine. Our task now? Ensuring the life-saving innovations we already have reach the people whose lives they can save.

No laughing matter

A gut-wrenching problem we can solve

Diarrhea used to be one of the biggest killers of kids—but now it’s one of the greatest global health success stories.

In 1997, I came across a New York Times column by Nick Kristof that stopped me in my tracks. The headline was “For Third World, Water Is Still a Deadly Drink,” and it included a statistic I almost didn’t believe: Diarrhea was killing 3.1 million people every year—most of them kids under the age of five.

I didn’t know much about the problem back then, except that it seemed so solvable. After all, in rich countries it felt like it already had been. My oldest daughter was a toddler at the time, and we never worried that an upset stomach would kill her. None of the other parents I knew worried about that either.

But in much of the world, kids without clean drinking water or basic sanitation were constantly being exposed to rotavirus, cholera, shigella, typhoid, and more—dangerous pathogens that spread easily when toilets are scarce and water is contaminated.

Nick’s column ended up changing my life. I sent it to my dad with a note: “Maybe we can do something about this.” He agreed. And after he traveled to Bangladesh to see the problem firsthand, we made a $40 million investment in vaccine research for diarrheal diseases. That grant helped shape what would become the Gates Foundation—and kickstarted decades of progress that’s now saved millions of lives.

Within a few years, I stepped away from Microsoft to focus on this work full-time. Once you’ve seen what’s possible in global health, it’s hard to do anything else.

When we first got involved, diarrhea was one of the biggest killers of kids worldwide. But over the past two and a half decades, these deaths have dropped by more than 70 percent.

The biggest breakthrough came from making vaccines for rotavirus, the leading cause of severe diarrhea and death in kids, affordable and accessible. When the vaccines first debuted in the early 2000s, they were priced at around $200 per dose—which meant they were completely out of reach for most families in most of the world. So the foundation partnered with vaccine manufacturers in India like Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute to develop high-quality, low-cost alternatives. Today, rotavirus protection costs about a dollar.

But getting the vaccines developed was only half the challenge. The other half was getting them to the kids who needed them most.

That’s where Gavi came in. The organization was set up a few years earlier to help low-income countries pay for lifesaving vaccines that had existed for decades but weren’t reaching the world’s poorest. But they were well-positioned to do the same with a new vaccine, and they did—purchasing the rotavirus vaccine for millions of children and supporting countries as they added it to their routine immunization programs. USAID played a huge role in this work, too, by helping local governments train community health workers and strengthen their vaccine delivery systems. Meanwhile, public health campaigns promoted treatments like oral rehydration salts and zinc supplements that can save a sick child's life for pennies. (Think of it as the medical-grade equivalent of Pedialyte.)

As all this was happening, countries quietly made enormous progress on clean water and sanitation too. Since 1990, 2.6 billion people around the world have gained access to safe drinking water—and the number of people who now have basic sanitation similarly has skyrocketed. These improvements help break a cycle where kids get sick, recover, and then get reinfected a few weeks later.

Despite the incredible progress, around 340,000 kids under five are still dying from diarrhea each year.

Part of the problem is that many kids still don't get vaccinated. Some live in places where health systems are weak or vaccines are hard to transport and store. Others are caught in conflict zones that make it dangerous for health workers to reach them.

And new challenges make the fight against diarrheal diseases even harder than it was 25 years ago. Shigella—one of the nastiest bacterial causes of diarrhea—is becoming more and more resistant to antibiotics, and we still don't have a vaccine. Climate change is making cholera and typhoid outbreaks more frequent, as floods contaminate water supplies and droughts force people to drink from unclean, unsafe sources.

For malnourished kids, everything is harder: They're more vulnerable to diarrheal diseases in the first place, and their damaged digestive tracts don't respond as well to oral vaccines or treatments. For families barely scraping by, diarrhea is both a medical crisis and an economic disaster. Parents miss work to care for sick kids. Kids miss school. Expenses pile up. It's one of the ways that disease keeps families trapped in poverty—and one of the reasons that a country’s public health is key to its development.

The encouraging news is that there’s a promising pipeline of innovations that builds on what we already know and could save even more lives.

At the foundation, we’re supporting scientists who are working on a vaccine for Shigella, which has become the leading bacterial cause of childhood diarrhea. We’re also funding efforts to combine different vaccines into a single shot, which would lower costs and make things easier for health workers and kids alike.

New delivery methods could make a big difference too. One example: vaccine patches for measles that don’t require needles, refrigeration, or trained staff to administer them. Just peel, stick, and protect.

We've already learned a lot about how chronic infections damage kids’ guts and make it harder for them to absorb nutrients or respond to vaccines. Now, scientists are researching how to repair that damage, which could help the sickest kids recover faster.

And outside the lab, environmental monitoring tools are being developed to detect early signs of outbreaks—by regularly testing sewage for typhoid, for instance. It’s like having an early warning system for epidemics.

We can’t afford to look away now

I’ve been talking about diarrhea for 25 years, even though it makes some people squeamish, because it’s a microcosm of global health. It’s proof that the world can come together to solve big problems. When we refuse to accept that some children won’t make it to their fifth birthday, we can save millions of lives.

But it’s also a warning of what can happen when we look away.

Right now, global health funding is being slashed around the world. According to one estimate, cuts to aid from the U.S. have already led to almost 60,000 additional childhood deaths from diarrhea. If nothing changes, by next January that number could rise to 126,000. These are projections, not final counts, but the reality is undeniable: When lifesaving programs are eliminated, kids pay the price.

Diarrhea is one of the most solvable problems in global health. We’ve come a long way, but we’re not done yet.

Bug fix

The buzz stops here

African scientists are engineering mosquitoes that can’t spread malaria.

A genetic cheat code

Moving ahead responsibly

No fever dream

How the U.S. got rid of malaria

This is how a parasite helped build the CDC and changed public health forever.

I spend a lot of time thinking and worrying about malaria. After all, it’s one of the big focuses of my work at the Gates Foundation. But for most Americans, the disease is a distant concern—something that happens “there,” not here.