The last chapter

My new deadline: 20 years to give away virtually all my wealth

During the first 25 years of the Gates Foundation, we gave away more than $100 billion. Over the next two decades, we will double our giving.

When I first began thinking about how to give away my wealth, I did what I always do when I start a new project: I read a lot of books. I read books about great philanthropists and their foundations to inform my decisions about how exactly to give back. And I read books about global health to help me better understand the problems I wanted to solve.

One of the best things I read was an 1889 essay by Andrew Carnegie called The Gospel of Wealth. It makes the case that the wealthy have a responsibility to return their resources to society, a radical idea at the time that laid the groundwork for philanthropy as we know it today.

In the essay’s most famous line, Carnegie argues that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” I have spent a lot of time thinking about that quote lately. People will say a lot of things about me when I die, but I am determined that "he died rich" will not be one of them. There are too many urgent problems to solve for me to hold onto resources that could be used to help people.

That is why I have decided to give my money back to society much faster than I had originally planned. I will give away virtually all my wealth through the Gates Foundation over the next 20 years to the cause of saving and improving lives around the world. And on December 31, 2045, the foundation will close its doors permanently.

This is a change from our original plans. When Melinda and I started the Gates Foundation in 2000, we included a clause in the foundation’s very first charter: The organization would sunset several decades after our deaths. A few years ago, I began to rethink that approach. More recently, with the input from our board, I now believe we can achieve the foundation’s goals on a shorter timeline, especially if we double down on key investments and provide more certainty to our partners.

During the first 25 years of the Gates Foundation—powered in part by the generosity of Warren Buffett—we gave away more than $100 billion. Over the next two decades, we will double our giving. The exact amount will depend on the markets and inflation, but I expect the foundation will spend more than $200 billion between now and 2045. This figure includes the balance of the endowment and my future contributions.

This decision comes at a moment of reflection for me. In addition to celebrating the foundation’s 25th anniversary, this year also marks several other milestones: It would have been the year my dad, who helped me start the foundation, turned 100; Microsoft is turning 50; and I turn 70 in October.

This means that I have officially reached an age when many people are retired. While I respect anyone’s decision to spend their days playing pickleball, that life isn’t quite for me—at least not full time. I’m lucky to wake up every day energized to go to work. And I look forward to filling my days with strategy reviews, meetings with partners, and learning trips for as long as I can.

The Gates Foundation’s mission remains rooted in the idea that where you are born should not determine your opportunities. I am excited to see how our next chapter continues to move the world closer to a future where everyone everywhere has the chance to live a healthy and productive life.

Planning for the next 20 years

I am deeply proud of what we have accomplished in our first 25 years.

We were central to the creation of Gavi and the Global Fund, both of which transformed the way the world procures and delivers lifesaving tools like vaccines and anti-retrovirals. Together, these two groups have saved more than 80 million lives so far. Along with Rotary International, we have been a key partner in reviving the effort to eradicate polio. We supported the creation of a new vaccine for rotavirus that has helped reduce the number of children who die from diarrhea each year by 75 percent. Every step of the way, we brought together other foundations, non-profits, governments, multilateral agencies, and the private sector as partners to solve big problems—as we will continue to do for the next twenty years.

Over the next twenty years, the Gates Foundation will aim to save and improve as many lives as possible. By accelerating our giving, my hope is we can put the world on a path to ending preventable deaths of moms and babies and lifting millions of people out of poverty. I believe we can leave the next generation better off and better prepared to fight the next set of challenges.

The work of making the world better is and always has been a group effort. I am proud of everything the foundation accomplished during its first 25 years, but I also know that none of it would have been possible without fantastic partners.

Progress depends on so many people around the globe: Brilliant scientists who discover new breakthroughs. Private companies that step up to develop life-saving tools and medicines. Other philanthropists whose generosity fuels progress. Healthcare workers who make sure innovations get to the people who need them. Governments, nonprofits, and multilateral organizations that build new systems to bring solutions to scale. Each part plays an essential role in driving the world forward, and it is an honor to support their efforts.

Of course, although the Gates Foundation is by far the most significant piece of my giving, it is not the only way I give back. I have invested considerable time and money into both energy innovation and Alzheimer’s R&D. Today’s announcement does not change my approach to those areas.

Expanding access to affordable energy is essential to building a future where every person can both survive and thrive. The bulk of my spending in this area is through Breakthrough Energy, which invests in companies with promising ideas to generate more energy while reducing emissions. I also started a company called TerraPower to bring safe, clean, next-generation nuclear technology to life. Both of these ventures will earn profits if successful, and I will reinvest any money I make through them back in the foundation, as I already do today.

I support a number of efforts to fight Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias. Alzheimer’s is a growing crisis here in the United States, and as life expectancies go up, it threatens to become a massive burden to both families and healthcare systems around the world. Fortunately, scientists are currently making amazing progress to slow and even stop the progress of this disease. I expect to keep supporting their efforts as long as it’s necessary.

The success in both areas will determine exactly how much money is given to the foundation since any profits they earn will be part of my overall gift.

What the Gates Foundation hopes to accomplish

Over the next twenty years, the foundation will work together with our partners to make as much progress towards our vision of a more equitable world as possible.

The truth is, there have never been more opportunities to help people live healthier, more prosperous lives. Advances in technology are happening faster than ever, especially with artificial intelligence on the rise. Even with all the challenges that the world faces, I’m optimistic about our ability to make progress—because each breakthrough is yet another chance to make someone’s life better.

Over the next twenty years, the foundation’s funding will be guided by three key aspirations:

In 1990, 12 million children under the age of 5 died. By 2019, that number had fallen to 5 million. I believe the world possesses the knowledge to cut that figure in half again and get even closer to ending all preventable child deaths.

We now understand the essential role nutrition—and especially the gut microbiome—plays in not only helping kids survive but thrive. We’ve made huge advances in maternal health, making sure that new and expectant mothers have the support they need to deliver healthy babies. We have new, life-saving vaccines and medicines, and we know how to get them to the people who need them most thanks to organizations like Gavi and the Global Fund. The innovation is there, the ability to measure progress is stronger than ever, and the world has the tools it needs to put all children on a good path.

Today, the list of human diseases the world has eradicated has just one entry: smallpox. Within the next couple years, I expect to add polio and Guinea worm to the list. (When we eradicate the latter, it will be a testament to the late President Jimmy Carter’s leadership.) I’m optimistic that, by the time the foundation shuts down, we can also add malaria and measles. Malaria is particularly tricky, but we’ve got lots of new tools in the pipeline, including ways of reducing mosquito populations. That is probably the key tool that, as it gets perfected and approved and rolled out, gives us a chance to eradicate malaria.

In 2000, the year that we started the foundation, 1.8 million people died from HIV/AIDS. By 2023, advances in treatment and preventatives cut that number to 630,000. I believe that figure will be reduced dramatically in the decades ahead, thanks to incredible new innovations in the pipeline—including a single-shot gene therapy that could reduce the amount of virus in your body so much that it effectively cures you. This would be massively beneficial to anybody who has HIV, including in the rich world. The same technology is also being used to treat sickle cell disease, an excruciating and deadly illness.

We’re also making huge progress on tuberculosis, which still kills more people than malaria and HIV/AIDS combined. Last year, a historic phase 3 trial began that could be the first new TB vaccine in over 100 years.

The key to maximizing the impacts of these innovations will be lowering their costs to make them affordable everywhere, and I expect the Gates Foundation will play a big role in making that happen. Health inequities are the reason the Gates Foundation exists. And the true test of our success will be whether we can ensure these life-saving interventions reach the people who need them most—particularly in Africa, South Asia, and across the Global South.

To reach their full potential, people need access to opportunity. That’s why our foundation focuses on more than just health.

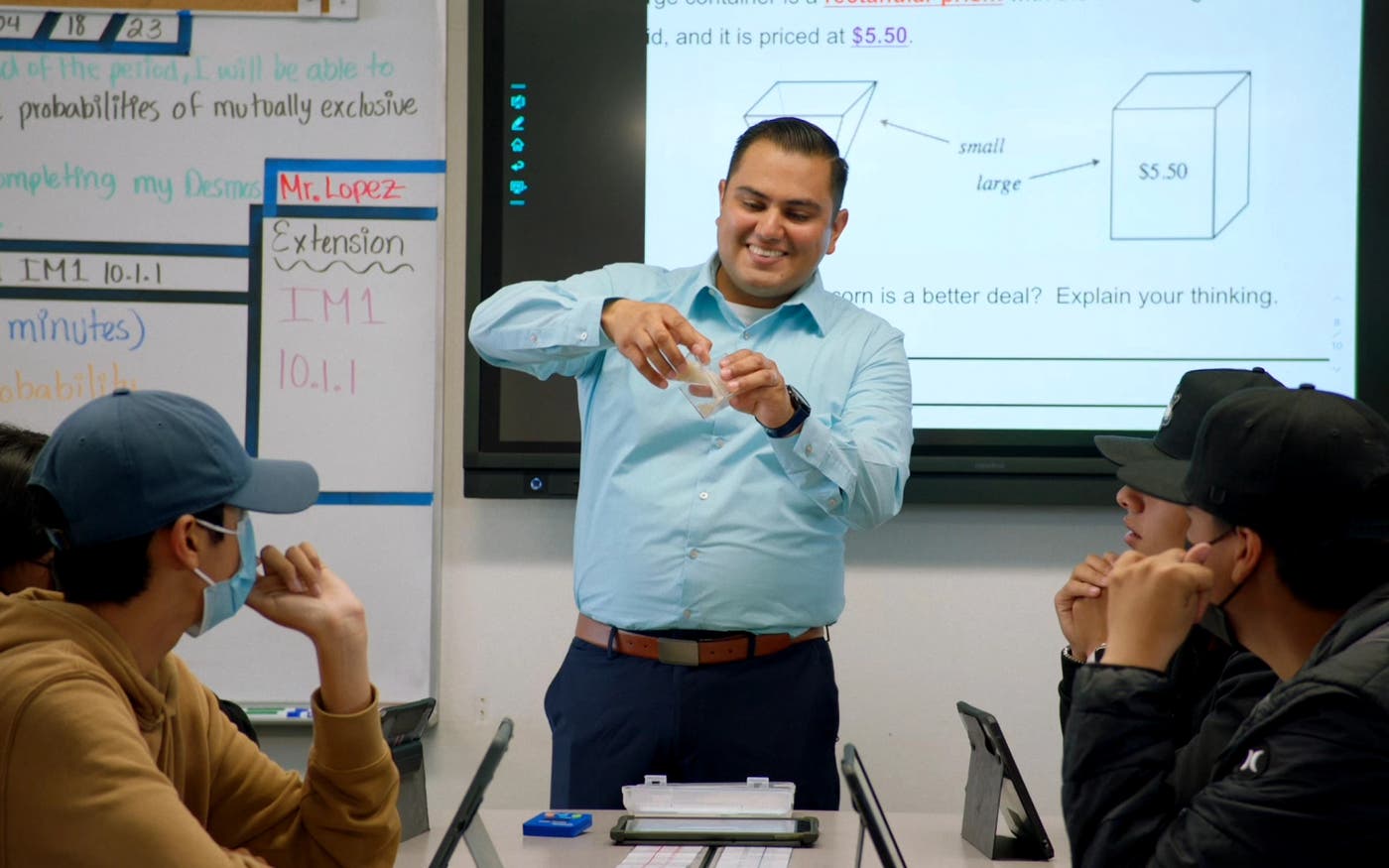

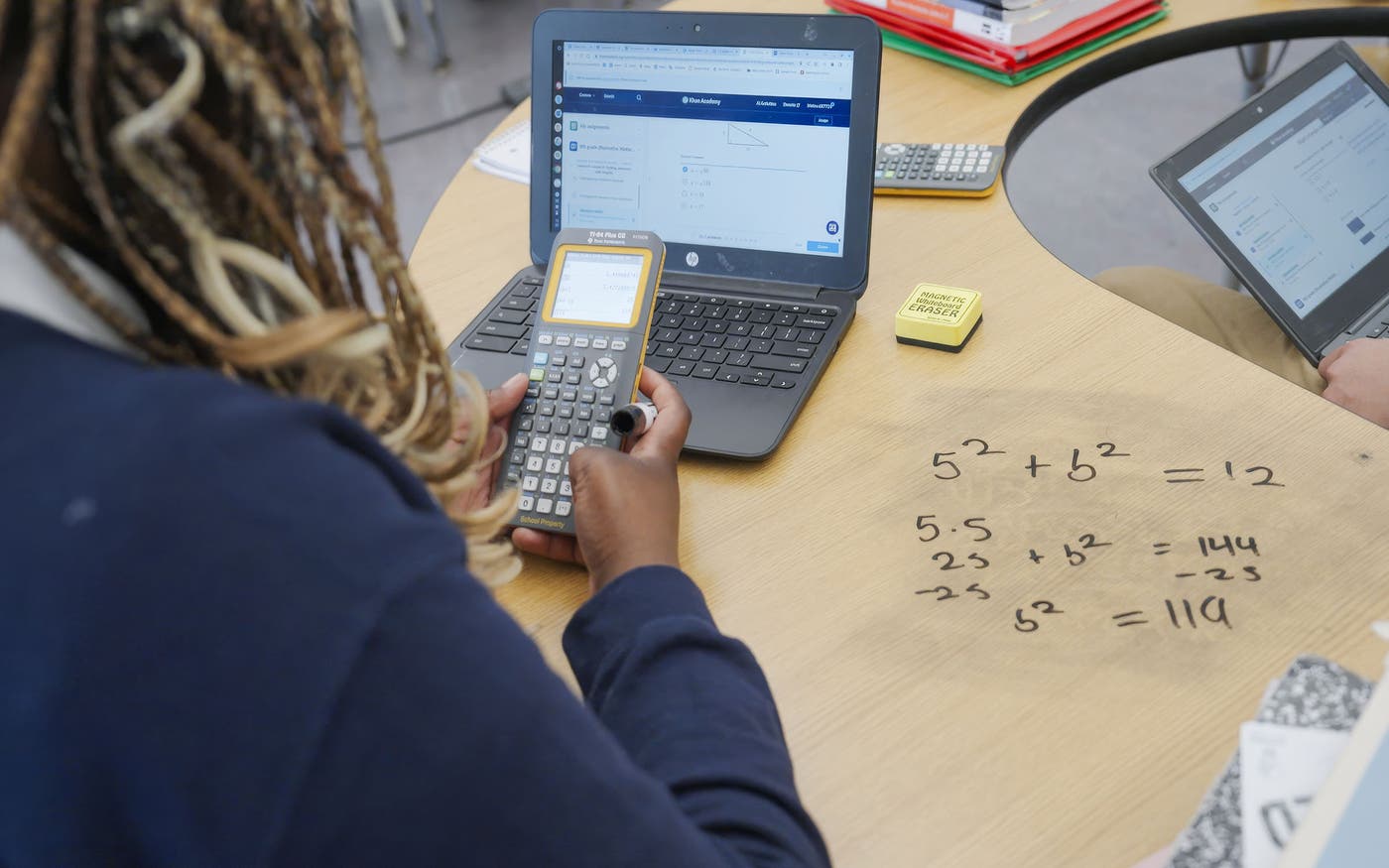

Education is key. Frustratingly, progress in education is less dramatic than in health—there is no vaccine to improve the school system—but improving education remains our foundation’s top priority in the United States. Our focus is on helping public schools ensure that all students can get ahead—especially those who typically face the greatest barriers, including Black and Latino students, and children from low-income backgrounds. At the K-12 level, that means boosting math instruction and ensuring teachers have the training and support they need—including access to new AI tools that allow them to focus on what matters most in the classroom. Given the importance of a post-secondary degree or credential for success nowadays, we’re funding initiatives to increase graduation rates, too.

As I mentioned, having access to a high-quality nutrition source is key to keeping kids’ development on track. Smallholder farmers form the backbones of local economies and food supplies, and they play a key role in making that happen. One of the main ways the foundation helps farmers is through the development of new, more resilient seeds that yield more crops even under difficult conditions. This work is even more important in a warming world, since no one suffers more from climate change than farmers who live near the equator. Despite that, I’m hopeful that we can help make smallholder farmers more productive than ever over the next two decades. Some of the crops our partners are developing even contain more nutrients—a win-win for both climate adaptation and preventing malnutrition.

We’ll also continue supporting digital public infrastructure, so more people have access to the financial and social services that foster inclusive economies and open, competitive markets. And we’ll continue supporting new uses of artificial intelligence, which can accelerate the quality and reach of services from health to education to agriculture.

Underpinning all our work—on health, agriculture, education, and beyond—is a focus on gender equality. Half the world’s smallholder farmers are women, and women stand to gain the most when they have access to education, health care, and financial services. Left to their own devices, systems often leave women behind. But done right, they can help women lift up their families and their communities.

The United States, United Kingdom, France, and other countries around the world are cutting their aid budgets by tens of billions of dollars. And no philanthropic organization—even one the size of the Gates Foundation—can make up the gulf in funding that’s emerging right now. The reality is, we will not eradicate polio without funding from the United States.

While it's been amazing to see African governments step up, it’s still not enough, especially at a moment when many African countries are spending so much money servicing their debts that they cannot invest in the health of their own people—a vicious cycle that makes economic growth impossible.

It's unclear whether the world’s richest countries will continue to stand up for its poorest people. But the one thing we can guarantee is that, in all of our work, the Gates Foundation will support efforts to help people and countries pull themselves out of poverty. There are just too many opportunities to lift people up for us not to take them.

The last chapter of my career

Next week, I will participate in the foundation’s annual employee meeting, which is always one of my favorite days of the year. Although it’s been many years since I left Microsoft, I am still a CEO at heart, and I don’t make any decisions about my money without considering the impact.

I feel confident putting the remainder of my wealth into the Gates Foundation, because I know how brilliant and dedicated the people responsible for using that money are—and I can’t wait to celebrate them.

I'm inspired by my colleagues at the foundation, many of whom have foregone more lucrative careers in the private sector to use their talents for the greater good. They possess what Andrew Carnegie called “precious generosity,” and the world is better off for it.

I am lucky to have been surrounded by many generous people throughout my life. As I wrote in my memoir Source Code, my parents were my first and biggest influences. My mom introduced me to the idea of giving back. She was a big believer in the idea of “to whom much is given much is expected,” and she taught me that I was just a steward of any wealth I gained.

Dad was a giant in every sense of the word, and he, more than anyone else, shaped the values of the foundation as its first leader. He was collaborative, judicious, and serious about learning—three qualities that shape our approach to everything we do. Every year, the most important internal recognition we hand out is called the Bill Sr. Award, which goes to the staff member who most exemplifies the values that he stood for. Everything we have accomplished—and will accomplish—is a testament to his vision of a better world.

As an adult, one of my biggest influences has been Warren Buffett, who remains the ultimate model of generosity. He was the first one who introduced me to the idea of giving everything away, and he’s been incredibly generous to the foundation over the decades. Chuck Feeney remains a big hero of mine, and his philosophy of “giving while living” has shaped how I think about philanthropy.

I hope other wealthy people consider how much they can accelerate progress for the world’s poorest if they increased the pace and scale of their giving, because it is such a profoundly impactful way to give back to society. I feel fulfilled every day I go to work at the foundation. It forces me to learn new things, and I get to work with incredible people out in the field who really understand how to maximize the impact of new tools.

Today’s announcement almost certainly marks the beginning of the last chapter of my career, and I’m okay with that. I have come a long way since I was just a kid starting a software company with my friend from middle school. As Microsoft turns 50 years old, it feels right that I celebrate the milestone by committing to give away the resources I earned through the company.

A lot can happen over the course of twenty years. I want to make sure the world moves forward during that time. The clock starts now—and I can’t wait to make the most of it.

Just the facts

Health aid saves lives. Don’t cut it.

Here’s the proof I’m showing Congress.

I’ve been working in global health for 25 years—that’s as long as I was the CEO of Microsoft. At this point, I know as much about improving health in poor countries as I do about software.

I’ve spent a quarter-century building teams of experts at the Gates Foundation and visiting low-income countries to see the work. I’ve funded studies about the effectiveness of health aid and pored over the results. I’ve met people who were on the brink of dying of AIDS until American-funded medicines brought them back. And I’ve met heroic health workers and government leaders who made the best possible use of this aid: They saved lives.

The more I’ve learned, the more committed I’ve become. I believe so strongly in the value of global health that I’m dedicating the rest of my life to it, as well as most of the $200 billion the foundation will give away over the next 20 years.

People in global health argue about a lot of things, but here’s one thing everyone agrees on: Health aid saves lives. It has helped cut the number of children who die each year by more than half since 2000. The number used to be more than 9 million a year; now it’s fewer than 5 million. That’s incontrovertible.

So when the United States and other governments suddenly cut their aid budgets the way they've been doing, I know for a fact that more children will die. We’re already seeing the tragic impact of reductions in aid, and we know the number of deaths will continue to rise.

A study in the Lancet looked at the cumulative impact of reductions in American aid. It found that, by 2040, 8 million more children will die before their fifth birthday. To give some context for 8 million: That's how many children live in California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio combined.

I’ve submitted written testimony on this topic, which you can read below, for the Senate Appropriations Committee hearing occurring later today. In it, I discuss what’s already happened and what needs to happen next.

Testimony to the United States Senate Committee on Appropriations

June 25, 2025

Over the past 25 years—the same span of time I spent leading Microsoft—I have immersed myself in global health: building knowledge, deepening expertise, and working to save lives from deadly diseases and preventable causes. During that time, I have built teams of world-class scientists and public health experts at the Gates Foundation, studied health systems across continents, and worked in close partnership with national and local leaders to strengthen the delivery of lifesaving care. I have visited hundreds of clinics, listened to frontline health workers, and spoken with people who rely on these programs. Earlier this month, I traveled to Ethiopia and Nigeria, where I witnessed firsthand the impact that recent disruptions to U.S. global health funding are having on lives and communities.

Global health aid saves lives. And when that aid is withdrawn—abruptly and without a plan—lives are lost.

Yet, in recent months, some have questioned whether the foreign assistance pause has caused harm. Concerns about the human impact of these disruptions have been dismissed as overstated. Some people have even claimed that no one is dying as a result.

I wish that were true. But it is not.

It is important to note that while this hearing is about the Trump Administration’s $9 billion recission package, what is really at stake is tens of billions of dollars in critical aid and health research that has been frozen by DOGE with complete disregard for the Congress and its Constitutional power of the purse.

In the early weeks of implementing the foreign aid freeze, DOGE directives resulted in the dismissal of nearly all United States Agency for International Development (USAID) staff and many personnel at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some funding was later restored to allow for the continuation of what has been categorized as "lifesaving" programs. However, to date that designation has been applied narrowly and with limited transparency, in an inconsistent manner, often prioritizing emergency interventions when a patient is already in critical condition over essential preventative or supportive care.

For example, providing a child with a preventive antimalarial treatment, ensuring access to nutrition so that HIV/AIDS medications can be properly administered, testing pregnant women for HIV to see if they are eligible for treatment to prevent transmission to their children or identifying and treating tuberculosis cases early have not consistently qualified for exemption. As a result, many of the programs delivering these services have been suspended, delayed, or scaled back.

Recent reporting from the New York Times has shed light on the devastating human cost of the abrupt aid cuts. One especially tragic example is Peter Donde, a 10-year-old orphan in South Sudan, born with HIV, who died in February after losing his access to life-saving medication when USAID operations were suspended. His story is one of many.

During my recent visit to Nigeria, I met with leaders from local nonprofit organizations previously funded by the United States. One group shared the remarkable progress they had made in tuberculosis detection and treatment. In just a few years, case identification increased from 25 percent to 80 percent, a critical step toward breaking transmission and reducing the overall disease burden. That progress has now stalled. The grants that enabled this work were tied to USAID staff who have been dismissed, and with their departure, the funding ended, and the work stopped.

The broader effects of these sudden shifts are difficult to overstate. For example, funding for polio eradication has been preserved in the State Department budget but cut from the CDC—even though the two agencies collaborate closely on the program. This type of fragmented decision-making has left implementing organizations uncertain about staffing and operations. Many no longer feel confident that promised U.S. funds will materialize, even when awards have been announced. In some cases, staff continue to work without pay. Some organizations are approaching insolvency.

Meanwhile, in warehouses across the globe, food aid and medical supplies sourced from American producers are sitting idle—spoiling or approaching expiration—because the systems that once distributed them have been disrupted. Clinics are closing. Health workers are being laid off. HIV/AIDS patients are missing critical doses of medication. Malaria prevention campaigns, including bed net distributions and indoor spraying, have been delayed or canceled, leaving hundreds of millions of people unprotected at the peak of transmission season.

Efforts to track data that would illustrate the severity of this worsening crisis have also been severely compromised. Many of the people responsible for collecting and reporting health information—health workers, statisticians, and program managers—have been laid off or placed on leave. The systems that once monitored health outcomes are shutting down, and the offices where that data was once analyzed now sit empty. As a result, the true scope of the harm is becoming harder to measure, just as the need for information is most urgent.

The situation we face is not about political ideology, and it is not a debate over fiscal responsibility. U.S. government spending on global health accounts for just 0.2 percent of the federal budget. Shutting down USAID did nothing to reduce the deficit. In fact, the deficit has grown in the months since.

Furthermore, many of the allegations regarding waste, fraud, and abuse have proven to be unsubstantiated. For example, the widely circulated claim that USAID sent millions of dollars’ worth of condoms to the Gaza Strip is inaccurate. In fact, the Wall Street Journal reported that the program allocated approximately $27,000 for condoms as part of an HIV transmission prevention initiative—not in the Middle East, but in Gaza Province, Mozambique.

What we are witnessing because of the rapid dismantling of America’s global health infrastructure is a preventable, human-caused humanitarian crisis—one that is growing more severe by the day. DOGE made a deadly mistake by cutting health aid and laying off so many people. But it is not too late to undo some of the damage.

A Record of Progress—and What is at Risk

Since 2000, child mortality worldwide has been cut in half. Deaths from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria have declined significantly. And we are on the verge of eradicating only the second human disease in history: polio. These are not abstract statistics; they represent tens of millions of lives saved. None of this progress would have been possible without consistent, bipartisan U.S. leadership and investment.

Over the past several decades, the United States has built one of its most strategic global assets: a respected and robust public health presence. This leadership is not just a humanitarian achievement—it is a core pillar of American soft power and security. For example, a Stanford study analyzing 258 global surveys across 45 countries found that U.S. health aid is strongly linked to improved public opinion of the United States. In countries and years where U.S. health aid was highest, the probability of people having a very favorable view of the United States was 19 percentage points higher. Other forms of aid—like military or governance—did not have the same effect. Another example is the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The rapid deployment of U.S. scientists, health workers, and CDC teams helped contain the virus before it could spread globally. Their presence allowed the U.S. to help shape the response strategy, speed up containment, and prevent a wider outbreak. Many African countries are facing the dual burden of rising debt and pressing health needs, forcing painful choices between repaying creditors, and protecting their citizens. Helping them navigate this challenge is not just the right thing to do—it is a strategic imperative. If the United States retreats, others will fill the gap, and not all of them will bring our values, our priorities, or our interests to the table. Preserving American global influence will require restoring the staff, systems, and resources that underpin it—before the damage becomes irreversible.

I understand the fiscal pressures facing Congress. I recognize the need to prioritize spending and to hold programs accountable for results. I also share the Trump Administration’s commitment to promoting efficiency and encouraging country-led solutions. But I believe those goals can—and must—be pursued while still protecting the programs that deliver the highest return on investment and the greatest impact on human lives.

The United States’ support for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) represent some of the smartest, most effective investments our country has ever made. These initiatives are proven, strategically aligned with American interests, and cost-effective on a scale few other government programs can match.

Together, Gavi and the Global Fund have helped save more than 82 million lives. Gavi has helped halve childhood deaths in the world’s poorest countries and returns an estimated $54 for every $1 invested. The Global Fund has contributed to a 61% reduction in deaths from HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. PEPFAR has saved over 26 million lives and helped millions of children be born HIV-free. GPEI has brought us closer than ever to the eradication of polio. Pulling back now would not only jeopardize these historic gains—it would invite a resurgence of preventable disease, deepen global instability, and undermine decades of bipartisan American leadership.

This is not a forever funding stream for the U.S. Government. These programs set out clear pathways for countries to “graduate” from aid, which many have already done. For example, nineteen countries, including Viet Nam and Indonesia, have successfully graduated from Gavi support and now fully finance their own immunization programs. Others—from Bangladesh to Cote d'Ivoire—are on track to do the same. This is how U.S. development policy should work: catalytic, cost effective, and designed to help countries become self-reliant and drive their own progress. I agree that aid funding should have an end date, but not overnight. The most effective path to that end date is innovation. By investing in the development and delivery of new medical tools and treatments, we can drive down the cost of care, and in some cases, make diseases that were once a death sentence treatable, or even curable. Advances in therapies for chronic conditions like sickle cell disease, HIV, or certain types of cancers could transform lives and health systems. American innovation offers a sustainable exit strategy—one that reduces long-term costs, allows the United States to responsibly step back, and builds lasting trust and good will that far exceed the original investment.

Over the past 25 years, the Gates Foundation has invested nearly $16 billion in global health partnerships like Gavi, the Global Fund, and GPEI. We will continue to invest, through innovation, research, and close coordination with partners. But no private institution—or coalition of them—can replace the scale, reach, or authority of the U.S. government in delivering lifesaving impact at the global level.

The decisions made in the coming weeks will shape not only the lives saved in the near term—but the legacy of American leadership for generations to come.

Download a PDF of the testimony with appendices that include reflections from Gates Foundation staff in Africa on the impact of the U.S. aid cuts; analytical projections from respected organizations; and a selection of first-hand reporting from reputable news organizations and journalists.

Everyday miracles

A perilous time for the world’s poorest children

My latest speech about why we need to keep funding vaccines.

I’ve been giving speeches about vaccines for 25 years. After so much time, it could have become routine for me. But it never has.

One reason is that the impact of vaccines—a single dose can protect a child from deadly diseases forever—is like a miracle to me, and who gets tired of talking about miracles?

The other reason is tied to this particular moment. There’s never been a point in the past 25 years when more lives hung in the balance. In all likelihood, 2025 will be the first year since the turn of the century when the number of children dying will go up instead of down.

Why? Governments are cutting health aid—including funds for Gavi, the vaccine organization that the Gates Foundation helped start. As a result, Gavi will likely not have all the money it needs to fund its next five years of work.

So when I spoke this week at a summit in Brussels where donors committed a new round of funding for Gavi, I focused on why it’s so important to keep the money flowing and maintain our momentum on vaccines. You can read my remarks below.

Remarks as delivered

June 25, 2025

Global Summit: Health & Prosperity through Immunisation

Brussels, Belgium

Good evening, and thank you to everyone joining us here tonight—and for all your support for one of the most transformative efforts in the world.

I want to particularly thank President von der Leyen and President Costa, and the European Union, for co-hosting this summit. President von der Leyen has long been an incredible champion for health and development, and the EU has been one of the Gavi's biggest supporters since the very beginning—support that's more crucial now than ever.

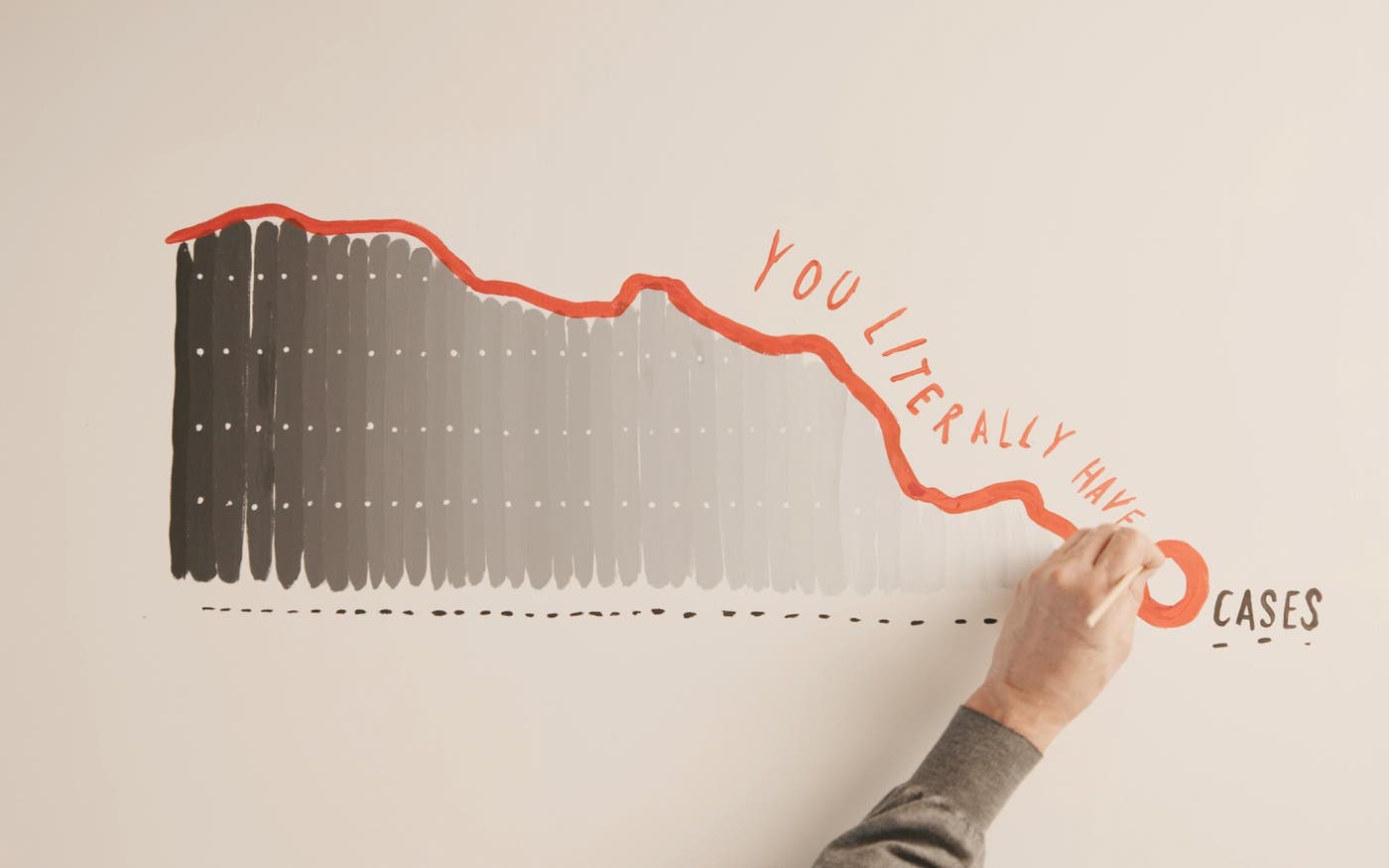

This chart is one that I think about a lot. It's really my most favorite chart. And I consider it almost kind of a report card for humanity. Because over the last 25 years, the reduction of under-five deaths has been far faster than any time in history. We've gone from over 9 million to now half as many deaths taking place by children. This is an unbelievable result.

And it doesn't fully state the benefit of these vaccines. The vaccines leave a lot of kids far more healthy, and so their ability to achieve their potential is increased.

Gavi prioritizes saving lives, and it's done with incredible scientific rigor. We're constantly improving vaccines. We're constantly looking at the safety, and I'm very proud of the work that's done to make sure that these vaccines are incredibly safe.

The founding of Gavi actually goes back to about the time the Gates Foundation was first started. And after 25 years, I can still say that it's at the top of the list of things that I'm very, very proud of. At that time, kids were not getting access to vaccines. They were too expensive. They hadn't been formulated properly. And I was stunned to learn that so many kids were dying from a disease like rotavirus because the vaccine wasn't getting out to all the children of the world.

So Gavi was created to not only help finance vaccines, but work with countries to adopt these new vaccines.

We've done an amazing job of getting these prices down. A good example is the pneumococcal vaccine, PCV. This vaccine became available in high-income countries the year that Gavi was founded. And it does a fantastic job of protecting kids against pneumonia, which was the single most deadly childhood infection. But it was very expensive.

And so Gavi and its partners incentivized vaccine manufacturers to develop a new, much cheaper PCV, which was introduced in 2017. Today, the manufacturers make PCV vaccines available to low-and middle-income countries for just $2 a dose.

And of course, we've seen similar reductions across all of the different vaccines, allowing us to add new vaccines to save even more children.

Since the founding of Gavi, the overall cost of fully vaccinating a child has been cut in more than half.

And we have a pipeline of new vaccines coming along, vaccines to address new diseases and that bring down costs even further.

A good example of this is the HPV vaccine. Cervical cancer, which HPV prevents, is the fourth most common cancer in women around the world. And this vaccine can prevent over 90% of these cases.

But countries were slow to adopt this vaccine, in part because it was hard to deliver: initially, it required three doses spread across six months.

Scientists believed that perhaps it could be done with fewer doses. And so the Gates Foundation funded a trial to see whether a single dose was essentially fully protective. And after seeing the incredible results, the WHO approved a single dose schedule in 2022.

Now, we have 75 countries around the world that have moved to this single dose approach.

And because the single dose is cheaper and easier to deliver, it's now getting to far more girls around the world. For example, after Nigeria introduced the single-dose vaccine, it was able to vaccinate more than 12 million girls in less than a year. That's really incredible.

Across Gavi countries, HPV vaccine coverage has increased dramatically. The year after this single-dose approval, we doubled the number of girls getting the vaccine. And [the next year] we doubled it again, and this year we'll double it again.

There's more than just making vaccines available. We have to work with our partner countries on helping improve their health systems. So the Gavi Alliance has spent a lot of its resources and a lot of its technical support in helping improve those primary health care systems, which are so vital. We've helped countries understand where they're missing kids and how to invest in raising those coverage levels.

As you've heard, over this 25-year period, that means over a billion children have been vaccinated—resulting in the saving of over 19 million lives.

Nineteen million is a big number. It's almost easier to understand if I just say: okay, here's a child whose life was saved. But you have to take your reaction to how valuable that is and multiply it by this absolutely gigantic number.

The total cost to save those lives was about $22 billion. And that means that Gavi saved children's lives for only about $1,000 per life saved.

And in addition, the kids who these vaccines have kept healthy not only go to school; they do well in school. They join the economy. They contribute to their country. And really, this is why improving health through vaccines is part of the formula for helping countries be self-sufficient.

Gavi's vaccination has generated $250 billion in economic benefits in the countries it supports. In fact, Gavi has had such an extraordinary economic benefit that over 19 countries that were Gavi recipients have now graduated, meaning they now fully fund their own immunization programs.

A great example is Indonesia. Since partnering with Gavi, it’s doubled the number of vaccines offered through its routine immunization program—and it’s seen childhood deaths fall to a quarter of what they were before. And now, Indonesia is not only transitioning to be fully self-supportive—it’s also become a Gavi donor.

Of course, this is a challenging time. All the progress we’ve made is at risk. Budgets are tight, and we all have to show our priorities when there’s tough trade-offs to be made.

There’s no denying: this is a global health crisis. Between the U.S. cuts and other funding cuts, in total, aid in total has gone down by 30 billion this year alone. It reinforces the incredible values being shown by the people who are showing up here today and being incredibly generous.

But with the cut in health resources, along with the financial situation a lot of these low-income countries are in, we are going to have a few years where things will go backwards.

As we think about this, think of a mother who will bring a baby wheezing for breath to a help center, and because the vaccines aren't available, that baby will not survive.

Think of a health worker trying to deal with a measles outbreak who, because there's less resources for that primary health care system or vaccines, that measles epidemic will continue.

This is agonizing. I mean, we have to put ourselves in the position of the parents who lose these children and how tough it must be for them to realize that the life could have been saved by a vaccine that costs just 30 cents.

So though our trend lines will briefly go into reverse, I believe that we can come back. I believe that we will resume that incredible progress that you saw.

I don't know if it'll be in two years or four years or six years, but I do know that as we bring these resources back, and we take advantage of an incredible pipeline of innovation, new drugs, new vaccines—lots of amazing things to help with these diseases—we will resume progress.

So everyone here, I'd say, is recommitting themselves, just like the Gates Foundation, to doubling down and staying committed.

You know, I'm not pessimistic. In fact, we have things like polio eradication that we are, as we say, this close to elimination. That'll be a mind-blowing thing. Likewise, malaria: we have tools, a variety of tools that brought together will give us a chance in the next 20 years to completely eradicate that as a disease, just like we're doing with polio.

This is all why the Gates Foundation is pledging $1. 6 billion to Gavi for this next five-year period. Thank you.

And it's why we'll invest billions in making sure that pipeline of new and lower-cost vaccines continues to make Gavi even more effective.

In closing, I think we can reflect on what Nelson Mandela once said: “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way it treats its children.”

In the last 25 years, Gavi has helped over a billion children live better, healthier lives—thanks to the extraordinary support of partners like you.

If we get this right, this trajectory of progress will continue for decades to come.

Thank you.

No laughing matter

A gut-wrenching problem we can solve

Diarrhea used to be one of the biggest killers of kids—but now it’s one of the greatest global health success stories.

In 1997, I came across a New York Times column by Nick Kristof that stopped me in my tracks. The headline was “For Third World, Water Is Still a Deadly Drink,” and it included a statistic I almost didn’t believe: Diarrhea was killing 3.1 million people every year—most of them kids under the age of five.

I didn’t know much about the problem back then, except that it seemed so solvable. After all, in rich countries it felt like it already had been. My oldest daughter was a toddler at the time, and we never worried that an upset stomach would kill her. None of the other parents I knew worried about that either.

But in much of the world, kids without clean drinking water or basic sanitation were constantly being exposed to rotavirus, cholera, shigella, typhoid, and more—dangerous pathogens that spread easily when toilets are scarce and water is contaminated.

Nick’s column ended up changing my life. I sent it to my dad with a note: “Maybe we can do something about this.” He agreed. And after he traveled to Bangladesh to see the problem firsthand, we made a $40 million investment in vaccine research for diarrheal diseases. That grant helped shape what would become the Gates Foundation—and kickstarted decades of progress that’s now saved millions of lives.

Within a few years, I stepped away from Microsoft to focus on this work full-time. Once you’ve seen what’s possible in global health, it’s hard to do anything else.

When we first got involved, diarrhea was one of the biggest killers of kids worldwide. But over the past two and a half decades, these deaths have dropped by more than 70 percent.

The biggest breakthrough came from making vaccines for rotavirus, the leading cause of severe diarrhea and death in kids, affordable and accessible. When the vaccines first debuted in the early 2000s, they were priced at around $200 per dose—which meant they were completely out of reach for most families in most of the world. So the foundation partnered with vaccine manufacturers in India like Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute to develop high-quality, low-cost alternatives. Today, rotavirus protection costs about a dollar.

But getting the vaccines developed was only half the challenge. The other half was getting them to the kids who needed them most.

That’s where Gavi came in. The organization was set up a few years earlier to help low-income countries pay for lifesaving vaccines that had existed for decades but weren’t reaching the world’s poorest. But they were well-positioned to do the same with a new vaccine, and they did—purchasing the rotavirus vaccine for millions of children and supporting countries as they added it to their routine immunization programs. USAID played a huge role in this work, too, by helping local governments train community health workers and strengthen their vaccine delivery systems. Meanwhile, public health campaigns promoted treatments like oral rehydration salts and zinc supplements that can save a sick child's life for pennies. (Think of it as the medical-grade equivalent of Pedialyte.)

As all this was happening, countries quietly made enormous progress on clean water and sanitation too. Since 1990, 2.6 billion people around the world have gained access to safe drinking water—and the number of people who now have basic sanitation similarly has skyrocketed. These improvements help break a cycle where kids get sick, recover, and then get reinfected a few weeks later.

Despite the incredible progress, around 340,000 kids under five are still dying from diarrhea each year.

Part of the problem is that many kids still don't get vaccinated. Some live in places where health systems are weak or vaccines are hard to transport and store. Others are caught in conflict zones that make it dangerous for health workers to reach them.

And new challenges make the fight against diarrheal diseases even harder than it was 25 years ago. Shigella—one of the nastiest bacterial causes of diarrhea—is becoming more and more resistant to antibiotics, and we still don't have a vaccine. Climate change is making cholera and typhoid outbreaks more frequent, as floods contaminate water supplies and droughts force people to drink from unclean, unsafe sources.

For malnourished kids, everything is harder: They're more vulnerable to diarrheal diseases in the first place, and their damaged digestive tracts don't respond as well to oral vaccines or treatments. For families barely scraping by, diarrhea is both a medical crisis and an economic disaster. Parents miss work to care for sick kids. Kids miss school. Expenses pile up. It's one of the ways that disease keeps families trapped in poverty—and one of the reasons that a country’s public health is key to its development.

The encouraging news is that there’s a promising pipeline of innovations that builds on what we already know and could save even more lives.

At the foundation, we’re supporting scientists who are working on a vaccine for Shigella, which has become the leading bacterial cause of childhood diarrhea. We’re also funding efforts to combine different vaccines into a single shot, which would lower costs and make things easier for health workers and kids alike.

New delivery methods could make a big difference too. One example: vaccine patches for measles that don’t require needles, refrigeration, or trained staff to administer them. Just peel, stick, and protect.

We've already learned a lot about how chronic infections damage kids’ guts and make it harder for them to absorb nutrients or respond to vaccines. Now, scientists are researching how to repair that damage, which could help the sickest kids recover faster.

And outside the lab, environmental monitoring tools are being developed to detect early signs of outbreaks—by regularly testing sewage for typhoid, for instance. It’s like having an early warning system for epidemics.

We can’t afford to look away now

I’ve been talking about diarrhea for 25 years, even though it makes some people squeamish, because it’s a microcosm of global health. It’s proof that the world can come together to solve big problems. When we refuse to accept that some children won’t make it to their fifth birthday, we can save millions of lives.

But it’s also a warning of what can happen when we look away.

Right now, global health funding is being slashed around the world. According to one estimate, cuts to aid from the U.S. have already led to almost 60,000 additional childhood deaths from diarrhea. If nothing changes, by next January that number could rise to 126,000. These are projections, not final counts, but the reality is undeniable: When lifesaving programs are eliminated, kids pay the price.

Diarrhea is one of the most solvable problems in global health. We’ve come a long way, but we’re not done yet.

Lung Story Short

A book about tuberculosis, and everything else

Here’s how John Green turned a forgotten disease into a #1 NYT bestseller.

What do Adirondack chairs, Stetson hats, the city of Pasadena, and World War I have in common? According to John Green, all of their origin stories include tuberculosis.

In his new book, John argues that it’s impossible to separate the deadliest disease in history from, well, the rest of history. Adirondack chairs were designed by a man who vacationed in the New York mountains—a popular spot for TB patients seeking fresh air—and soon became staples of sanatorium porches across the country. John B. Stetson, who had TB himself, traveled west for dry mountain air and invented the cowboy hat to protect from sun, wind, and rain. Pasadena became a hub for TB treatment in the late 1800s, and TB “tourism” was a major driver of the city’s early economy, real estate, and identity. And the teenage assassins who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which kicked off World War I? They were more willing to die for their cause since they were already dying of TB.

No wonder John calls this book Everything Is Tuberculosis. In so many ways, TB shaped the world we live in. Even though the disease is now both rare and treatable in rich countries, in poorer places it’s on the rise and still a death sentence for so many.

John is best known as the author of some of the best young adult novels of all time (at least according to my daughter Phoebe, whose encouragement led me to read The Fault in Our Stars and Turtles All the Way Down). So a lot of people were surprised when he announced that his next book would be about global health—about a disease most people in the western world think of in the past tense.

I wasn’t. After all, I first met John over a decade ago, when he joined me on a Gates Foundation trip to Ethiopia. While traveling, we talked about a lot of the big questions John wrestles with in Everything Is Tuberculosis—like why the place a person is born influences their odds of surviving childhood (or childbirth), and what people like us can do to increase those odds.

Since then, John has been an invaluable partner to the foundation, bringing his curiosity and clarity to our events and helping raise awareness of our work. But he’s also become a powerful advocate for global health in his own right. I don’t know anyone else who could turn a book about tuberculosis into a number one New York Times bestseller.

Everything Is Tuberculosis is poignant, smart, and at times infuriating. At its heart is the story of a boy named Henry, whom John met at a TB clinic in Sierra Leone. Henry was just six when he started showing classic signs of the disease: fatigue, weight loss, night sweats. But the first tests he got came back negative, so he was sent home from the hospital. By the time he was eventually diagnosed, Henry was already very sick.

He began treatment with the standard cocktail of decades-old antibiotics. It’s a brutal regimen that involves months of pills, painful injections, constant side effects—and, once the infection starts to subside, aching hunger from having an appetite again. The drugs only work if they’re taken consistently and on schedule, but that’s often unrealistic for patients. In much of the world, TB treatment means walking miles to a clinic, missing work or school, going into debt, and facing social stigma and isolation. Even though Henry’s mom did everything she could to support him, there were interruptions to his treatment, and eventually the TB became drug-resistant.

In the end, Henry got lucky. Even as he got sicker and ran out of options, his doctors wouldn’t give up on him. They fought to get him access to a personalized drug regimen—something that’s rarely available to kids in poor countries. That care ended up saving his life, and today Henry is thriving. After years stuck in the hospital, he’s caught up academically and now in university (and even has a YouTube channel where he shares his journey and advocates for other TB patients). John doesn’t romanticize Henry’s story as some kind of miracle. Instead, he uses it as proof: that TB is curable, that good care works, and that the real question isn’t whether we can save lives—but whether we’re willing to make that care available to everyone.

Even though John finished writing the book last year, he nails the urgency of this moment. He shows how a disease that most people in rich countries have forgotten is still killing over a million people a year, and how easily that number could keep climbing. That’s especially true now, as foreign aid cuts disrupt TB care across the globe. Henry might not be alive today if it weren’t for organizations like Partners In Health—funded in part by U.S. health aid—which fought to get him the treatment he needed. These aid cuts will be devastating for kids like him, who may lose access to treatment altogether. They’ll also lead to more interrupted care, more cases, more drug resistance, and more strains of an infectious disease that will be harder and more expensive for the entire world to contain.

This is a book about the central challenge of global health today: the reality that, in John’s words, “the cure is where the disease is not, and the disease is where the cure is not.”

A book about tuberculosis could be pretty boring, but John makes it super compelling by weaving in TB’s long and strange history, from the myth that it only afflicted white people, to the theory that it inspired creative genius, to its influence on Victorian beauty standards. (I didn’t know about those last two… or the Stetson hats.) If you’re familiar with John’s work, this approach won’t surprise you. He has a gift for getting people to care about things they might not think are “for me,” whether that’s poetry, astrophysics, or infectious disease.

John ends Everything Is Tuberculosis with a stirring call to action. He makes the case that saving lives from TB isn’t really a scientific challenge anymore; it’s a moral one. I largely agree. But I also think there are more reasons for hope than the book lets on.

While John is clear-eyed about the failures of the past and present—the slow pace of progress, the sky-high prices of new TB drugs, the inequality that determines who gets treated and who doesn’t—he doesn’t spend much time on what comes next. Having spent the last two-and-a-half decades investing in the science behind TB care through the Gates Foundation, I’ve seen a different side of the story. I know what’s in the pipeline, and I know what’s possible.

Today, we’re closer than ever to breakthroughs that could change everything about how we treat and even prevent TB: shorter drug regimens, better diagnostics, and even vaccines. These tools will only make a difference if they’re affordable enough to reach kids like Henry. But I think it’s important to recognize that the companies often criticized for pricing are also, ironically, the only ones that have been willing to invest in TB at all. We need to keep working with them as partners, keep the innovation coming, and keep bringing costs down.

If we do, we can make Henry’s story of survival the norm, not the exception—and make tuberculosis a disease of the past, not the future.

My look back

The breakthrough that transformed the Gates Foundation

This is the story of how better data helped us cut child mortality in half.

We started the Gates Foundation 25 years ago to save and improve children’s lives. But no one can solve a problem they don’t fully understand. And back in 2000, the world’s understanding of childhood mortality was occasionally inaccurate, often imprecise, and almost always incomplete.

That’s why I believe the breakthrough that transformed our foundation in the two-and-a-half decades since wasn’t a single vaccine or treatment—it was a revolution in the world’s understanding of childhood mortality. Through advances in how researchers collect and analyze global health data, we now know much more about what kills children, where these deaths occur, and why some kids are more vulnerable than others. By putting those insights to work, we’ve been able to save lives.

The first challenge was knowing exactly what was killing children.

Reading the 1993 World Development Report opened my eyes to the scale of the problem: Around 12 million children under the age of five were dying every year, with a staggering disparity between rich and poor countries. But the available data was fragmented and inconsistent. That made it difficult to understand trends or allocate resources effectively.

So the foundation helped create the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, to give a permanent home to the Global Burden of Disease study—originally developed in the 1990s by researchers at Harvard University and the World Health Organization. We wanted to expand it from a static snapshot of the problem into a regularly updated tool that tracked how diseases impact people around the world. That gave us something the world never had before: a comprehensive—and current—picture of child mortality across every country.

Measuring symptom-based causes of children’s deaths was an important step. But broad disease categories like “diarrhea” or “respiratory infection” didn’t give us enough information to act on. We needed to know which specific pathogens were responsible for the most common and fatal cases. So the Gates Foundation funded two landmark studies to find out.

In 2013, the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, or GEMS, found that rotavirus was causing 20 percent of lethal diarrhea cases in kids. At the time, diarrhea was the second-leading infectious killer of children. While oral rehydration therapy had already helped bring down deaths over previous decades, GEMS helped fast-track the rollout of a more targeted tool—a new rotavirus vaccine—in the hardest-hit countries, in close partnership with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

A year later, the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study, or PERCH, revealed that respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, was a much more common cause of severe pneumonia—the leading infectious killer of kids around the world—than previously understood. (And not just in low- and middle-income countries, where 97 percent of RSV deaths occur, but in higher-income ones too, where the virus still fills pediatric hospital wards each winter.) That prompted us to expand our investments in RSV prevention, which led to the approval of the first maternal vaccines for RSV in 2023.

But understanding what causes childhood mortality wasn’t enough on its own, because deaths aren’t distributed evenly across countries—or even within them. That’s why our second challenge was to figure out where exactly children were dying.

At the time, most health data was collected at national or regional levels. That masked major differences in disease burden from one community to the next—and made it harder to target interventions effectively.

To solve this second challenge, the foundation invested in new approaches to health mapping that combined satellite imagery, GIS technology, GPS data, and local health surveys. These maps gave Ministries of Health and implementing partners unprecedented, anonymized detail about disease patterns and population distribution, down to individual neighborhoods, that transformed how and where public health resources are deployed—while still preserving the privacy of the individual children and families in these places.

In Pakistan—one of just two countries where wild polio remains endemic—advanced mapping tools have helped vaccination teams reach and protect kids in settlements that weren’t on any official maps. Across sub-Saharan Africa, better geographic data has transformed the fight against malaria by revealing that transmission often clusters in small, hyper-local pockets. Through the Malaria Atlas Project, countries like Nigeria can now track those patterns more precisely—and then get bed nets, testing, and treatment where they’ll have the greatest impact.

With better knowledge of what was killing children, and where, one more fundamental question remained: Why might one child die from a disease while another—who lives in the same place, faces the same risks, and gets the same treatment—survives? This was our third big challenge.

In theory, traditional autopsies would provide the answer. But in the places where most childhood deaths still occur, these invasive procedures are often impossible to perform—too costly, and sometimes opposed for religious, cultural, or personal reasons.

So in 2015, the foundation launched the Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance network, or CHAMPS, which now operates in nine countries across Africa and South Asia. Working with in-country partners, CHAMPS pioneered a new autopsy alternative—using minimally invasive tissue sampling—that can determine causes of death quickly and accurately while respecting local customs and beliefs.

Through CHAMPS, we discovered that childhood deaths rarely have a single cause. Instead, kids often have multiple conditions at the same time, with malnutrition frequently leaving them much more vulnerable to a whole host of infections. (While it rarely shows up on death certificates, it’s an underlying cause of death in nearly half of all child mortality cases.) That finding helped solidify nutrition as a core focus of the foundation’s global health work—and the research, innovation, and product development we invest in. On the ground, we’re supporting partners as they integrate nutrition screening into routine care and train healthcare workers to manage multiple risks at once.

CHAMPS also demonstrated that inadequate prenatal care is responsible for a majority of stillbirths, newborn deaths, and maternal deaths, prompting us to further expand access to maternal health services—like prenatal vitamins and AI-enabled ultrasounds—in the communities where we work.

But the biggest takeaway from CHAMPS is also the most hopeful—and a reminder of why we started the Gates Foundation in the first place: So many childhood deaths could be prevented with existing interventions. We just need to ensure they reach the right children at the right time.

Twenty-five years in, our work on child mortality is far from complete. Still, the impact of what we have learned has been enormous

The Global Burden of Disease, GEMS, and PERCH studies helped shift global priorities by showing the world what was really killing kids—and where new vaccines and treatments could make the biggest difference. Better geospatial tools have empowered countries to pinpoint disease hotspots, find previously unmapped settlements, and distribute life-saving resources where they’re needed most. And CHAMPS is giving governments better data on why children are dying—data that’s now shaping policies, improving reporting, and guiding more effective care.

Most importantly, even as the number of children born every year has gone up, the number of overall childhood deaths has fallen by more than half—from 11.3 million in 1990 to 4.5 million in 2022. Playing a part in making that happen is the best job I’ve ever had, and the most meaningful work I’ve ever done.

At the Gates Foundation, we used to say we could cut child mortality in half again by 2040. The truth, though, is that goal feels further out of reach now—not because the science has stalled, but because support for global health has. The progress we’ve been part of was only possible because governments around the world, including here in the U.S., made long-term commitments to saving lives and followed through. That kind of leadership gave millions of children who would have died a chance at life—and made life better for millions more.

The last 25 years have shown us what’s possible. The next 25 will depend on whether the world keeps showing up for the children who need it most.

My look ahead

What it takes to take a breath

New tools can help millions more newborns—and their mothers—survive.

In a rural health clinic, a baby tries to take her first breath.

But her lungs aren’t ready. Because she was born too early, they haven’t developed the slick, soap-like substance that keeps her air sacs from collapsing. Without that substance—called lung surfactant—breathing becomes a desperate, exhausting act.

She’s suffering from respiratory distress syndrome, or RDS, a life-threatening condition that appears within hours of birth in premature babies. Unless she gets treatment, her oxygen levels will plummet and her organs will begin to shut down. In one study from India, every baby born with RDS outside of a hospital setting died. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, RDS is responsible for almost half of all neonatal deaths.

At hospitals in higher-income countries, there’s a way to save her: a liquid form of organically-derived surfactant delivered directly into the lungs. But the procedure requires a highly-trained specialist to guide a breathing tube down the newborn’s windpipe—avoiding the stomach and placing it just right—at a cost of up to $20,000. In many parts of the world, that kind of care simply doesn’t exist.

But what if any healthcare worker anywhere in the world could simply hold a small nebulizer to the baby's face and deliver surfactant as an easy-to-administer inhalant?

This breakthrough—a synthetic surfactant that’s stable enough to be delivered through a nebulizer—is still in development, drive in part by Gates Foundation-supported research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, and The Lundquist Institute. But its promise is extraordinary: an RDS treatment that costs less to make, doesn’t require a specialist to administer, and eliminates the need for intubation.

In other words, a therapy currently limited to the most advanced hospitals could become accessible in rural clinics and community settings around the world. Even in places with top-tier care, it could make treatment gentler, faster, and easier to deliver. In the United States—where RDS still affects 24,000 newborns a year—it could reduce the risks that come with intubating babies who might weigh only two or three pounds.

It’s the kind of innovation that could help solve one of the most persistent problems in global health: delivering intensive care without an intensive care unit, and helping millions more babies survive their first, most fragile moments.

Since 1990, the mortality rate for children under five has been cut by more than half—an amazing mark of global progress. But another statistic hasn’t fallen as fast: the number of babies who die in their first month of life.

Each year, 2.3 million newborns don’t survive past their first 28 days. And the day a baby is born is the most dangerous day of their life. The single biggest cause of these deaths is prematurity. Nearly 900,000 babies a year die from complications related to being born too soon, including infection, underdeveloped organs, and RDS.

Lower cost, easier-to-deliver surfactant is one way to give newborns a fighting chance, but it’s not the only way. Around the world, simple, affordable interventions already exist to identify at-risk pregnancies earlier, prevent more preterm births, and ensure a healthy birthing experience for mothers. Not only are these tools designed to work in the hardest-to-reach places—many of them start working even before a baby takes that first breath.

One of these innovations is a new type of ultrasound that’s changing who can catch the risks of preterm birth—and where.

Around the world, two thirds of women never get an ultrasound screening during pregnancy. Traditional machines are bulky and expensive, with specialized training required to operate them and interpret their results. In places where medical resources are already stretched thin, these types of ultrasounds are rarely an option.

But now, we have ultrasound devices about the size of a phone that can be operated by a nurse or midwife—no on-site specialist required. They weigh less than a pound. They process scans instantly. Their AI interface automatically detects high-risk conditions, like a shortened cervix or signs of early labor, so patients are referred for further care. And they have built-in telehealth functions to share images with remote specialists when needed.

By finding and flagging risks early, these AI-enabled ultrasounds are giving healthcare workers more time to act. In some cases, that means transferring the mother to a higher-level facility. In others, it means providing her with antenatal steroids—an inexpensive, underused treatment that speeds up fetal lung development—and, when needed, medications that delay labor just long enough for those steroids to take effect.

Early warning is essential, but we can save even more lives by going further upstream, starting with the health of pregnant women themselves.

In many low-income countries, undernutrition isn’t an exception. It’s the norm. And the intense demands of pregnancy make nutritional deficiencies even worse—putting mothers at increased risk of complications or death in childbirth, and raising the odds of early labor, low birth weight, and developmental delays for their babies.

But there’s a surprisingly simple fix: a daily supplement called MMS, or multiple-micronutrient supplementation, developed by the United Nations. It contains 15 essential vitamins and minerals for pregnancy—like zinc to reduce the risk of early labor, folic acid to help prevent birth defects, iron and vitamin D for healthy birth weight, and iodine for brain development. For an entire pregnancy, it costs just $2.60.

If MMS became the standard prenatal supplement in every low- and middle-income country, it could save nearly half a million newborn lives each year—and prevent serious complications in 25 million births by 2040.

The innovations above focus on treating, detecting, and preventing premature birth, a huge threat to newborn survival. But one of the most powerful ways to protect babies, preterm or full-term, is by ensuring their mothers stay healthy through pregnancy and childbirth.

When a woman dies during delivery, her baby is 46 times more likely to die in that first month of life. That’s why any serious effort to tackle infant mortality must also address postpartum hemorrhage—which tragically kills 70,000 women a year and is the leading cause of maternal mortality. Fortunately, two innovations are already helping healthcare workers catch and treat it before it becomes fatal.

The first is a calibrated drape—a simple plastic sheet placed under a woman during delivery that collects blood and shows, through printed measurement lines, exactly how much she’s losing. It gives healthcare workers a fast, accurate way to spot dangerous bleeding before it becomes life-threatening. The second is a one-time, 15-minute iron infusion during pregnancy that treats severe anemia—so if a woman does hemorrhage during childbirth, she’s less likely to experience catastrophic blood loss and more likely to survive.

Neither of these tools is complicated or expensive. But in combination, they can make a life-or-death difference for mothers and the babies who depend on them.

Taken together, these innovations form a chain of survival. They help mothers stay healthy through pregnancy. They detect problems before they become emergencies. They give fragile newborns a fighting chance. And they make it possible for families to celebrate a baby’s birth rather than mourning a loss.

Some of these tools are already saving lives. Others are on the verge of doing so. But their impact will be limited unless we prioritize and fund their delivery, not just their development. The world needs to make sure these innovations don’t get stuck in labs or warehouses—so they can reach the mothers and babies who need them most.

PrEP talk

From once a day to twice a year

Long-acting preventatives will save more lives from HIV/AIDS.

I’ve been working in global health for two and a half decades now, and the transformation in how we fight HIV/AIDS is one of the most remarkable achievements I’ve witnessed. (It’s second only to how vaccines have saved millions of children's lives.)

At the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, an HIV diagnosis was often a death sentence. But in the years since, so much has changed. Today, not only do we have anti-retroviral medications that allow people with HIV to live full, healthy lives with undetectable viral loads—meaning they can’t transmit the virus to others. We also have powerful preventative medications known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, that can reduce a person’s risk of contracting the virus by up to 99 percent when taken as prescribed. It’s an incredible feat of science: a pill that virtually prevents HIV contraction.

In theory, if we could get these tools to everyone who needs them and make sure they’re used correctly, we could stop HIV in its tracks. Because when people with the virus receive proper treatment, they can’t transmit it to others. And when people at risk take PrEP, they can’t contract it. In practice, however, getting these tools to people—and making sure they’re used correctly—is the hard part. Especially for PrEP.

That’s because current preventatives require people to take medication every single day. Miss a dose, and protection drops. It’s like trying to remember to lock your front door 365 times a year—if you mess up once, you’re vulnerable. For many people, the barriers stack up quickly. Some have to walk hours to reach a clinic. Others struggle to store medication safely or discreetly at home. And many face judgment and stigma for taking PrEP, especially young women in conservative communities. The very act of protecting yourself can lead to being shamed or ostracized.

That’s why I’m so excited about a new wave of innovations in HIV prevention. Scientists are in the process of developing several longer-lasting PrEP breakthroughs, each with distinct advantages that could help more people protect themselves on their own terms.

Lenacapavir, which requires only two doses per year through injection, could open HIV prevention up to people who can’t make frequent clinic visits. Cabotegravir, another injectable option that works for two months at a time, offers a more flexible dosing schedule than daily PrEP pills, too. Meanwhile, a monthly oral medication called MK-8572, still in the trial stage, could provide an alternative for people who prefer pills to injections. The Gates Foundation is even exploring ways to maintain a person’s protection for six months or longer. And researchers are working on promising PrEP options that include contraception, which would be particularly valuable for women who need both types of protection.

To understand how these options work in real life, and not just in labs, our foundation has supported implementation studies in South Africa, Malawi, and elsewhere. Unlike traditional clinical trials that test safety and efficacy in highly controlled settings, these studies examine how medications fit into people’s lives and work in everyday circumstances—looking at ease of use, cultural acceptance, and other practical challenges. This real-world understanding is crucial for successful adoption.

Some people ask me if these new preventative tools mean the Gates Foundation has given up on finding an HIV vaccine. Not at all. In fact, these advances push us to aim even higher in our research for a vaccine that could prevent HIV for a lifetime—and not just a few months at a time. Our goal is to create multiple layers of protection, much like modern cars have seatbelts, airbags, and even collision-warning sensors. Different tools work better for different people in different ways, and we need every tool we can get.

But even the most brilliant innovations make no difference unless they reach the people who need them most. This is where partnerships become crucial. Through grants to research institutions around the world, the foundation is working to lower manufacturing costs for HIV drugs so they’re accessible to everyone, everywhere. Then there are organizations like the Global Fund and PEPFAR, which have been instrumental in turning scientific advances into real-world impact.

The Global Fund—which needs to raise significant new resources next year to continue its work—currently helps more than 24 million people access HIV prevention and treatment. And PEPFAR has saved 25 million lives since its inception in 2003—a powerful example of how American leadership can build tremendous goodwill while transforming the world. Motivated by the belief that no person should die of HIV/AIDS when lifesaving medications are available, President George W. Bush created PEPFAR with strong bipartisan backing and it continues to serve as a lifeline to millions of people.

We're at a pivotal moment in this fight. Twenty years ago, many believed it would be impossible to deliver HIV treatment at scale in Africa’s poorest regions. Since then, we’ve made fantastic progress. Science has shown us promising paths forward—for better prevention options, easier treatment regimens, and, maybe one day, an effective vaccine. Our task now? Ensuring the life-saving innovations we already have reach the people whose lives they can save.

Bite back

Great news for mosquito haters

With some breakthrough tools, the end of malaria could be here soon.

I was scrolling Reddit recently when I saw a video of a mosquito trying and failing to suck someone’s blood. Some of the replies were pretty funny, but I noticed that most of them were just some form of “How do I get this person’s superpower?” It was a great reminder of how universally hated these bloodsuckers are.

But I have good news—for Reddit users and everyone else: Real progress has been made in the fight against mosquitoes and specifically against malaria, the deadliest disease they carry. And I believe we’ll soon have the transformational tools needed to end malaria entirely.