Hands off the wheel

The rules of the road are about to change

I believe we’ll reach a tipping point with autonomous vehicles within the next decade.

I’ve always been a car guy. When I was younger, I used to love driving fast (sometimes too fast). Now, I look forward to my daily commute to work. There’s something so fun yet meditative about driving a car.

Despite that, I’m excited for the day I get to hand over control of my car to a machine.

That day is coming sooner rather than later. We’ve made tremendous progress on autonomous vehicles, or AVs, in recent years, and I believe we’ll reach a tipping point within the next decade. When it happens, AVs will change transportation as dramatically as the PC changed office work. A lot of this development has been enabled by the progress made in artificial intelligence more broadly. (I recently shared my thoughts about AI on this blog. You can read them here.)

Some background for those who might not know a lot about AVs: The best way to understand where we are today is by looking at the Society of American Engineers, or SAE, classification system. This is widely used to describe how autonomous a vehicle is.

In levels 0-2, a human driver is in full control of the car, but the vehicle can provide assistance through features like adaptive cruise control and lane centering. Level 3 is when the technology starts to move from the driver being in control to the vehicle being in control. By the time you reach the highest level, the car can be fully autonomous at all times and under all conditions—the level 5 vehicles of the future might not have steering wheels at all.

Right now, we’re close to the tipping point—between levels 2 and 3—when cars are becoming available that allow the driver to take their hands off the wheel and let the system drive in certain circumstances. The first level 3 car was recently approved for use in the United States, although only in very specific conditions: Autonomous mode is permitted if you’re going under 40 mph on a highway in Nevada on a sunny day.

Over the next decade, we’ll start to see more vehicles crossing this threshold. AVs are rapidly reaching the point where almost all of the technology required has been invented. Now, the focus is on refining algorithms and perfecting the engineering. There have been huge advances in recent years—especially in sensors, which scan the surrounding environment and tell the vehicle about things it needs to react to, like pedestrians crossing the street or another driver who swerves into your lane.

There are a lot of different approaches to AVs in development. Many vehicle manufacturers—like GM, Honda, and Tesla—are working on models that look like regular cars but have autonomous features. Then there are companies entirely focused on AVs, some of whose products are pushing the boundaries of what a vehicle can be—like a perfectly symmetrical robotaxi or public transit pods. Many others are developing components that can be installed to give an existing vehicle autonomous capabilities.

I recently had the opportunity to test drive—or test ride, I guess—a vehicle made by the British company Wayve, which has a fairly novel approach. While a lot of AVs can only navigate on streets that have been loaded into their system, the Wayve vehicle operates more like a person. It can drive anywhere a human can drive.

When you get behind the wheel of a car, you rely on the knowledge you’ve accumulated from every other drive you’ve ever taken. That’s why you know what to do at a stop sign, even if you’ve never seen that particular sign on that specific road before. Wayve uses deep learning techniques to do the same thing. The algorithm learns by example. It applies lessons acquired from lots of real world driving and simulations to interpret its surroundings and respond in real time.

The result was a memorable ride. The car drove us around downtown London, which is one of the most challenging driving environments imaginable, and it was a bit surreal to be in the car as it dodged all the traffic. (Since the car is still in development, we had a safety driver in the car just in case, and she assumed control several times.)

It’s not clear yet which approaches will be the most successful, since we’re only starting to reach the threshold where cars become truly autonomous. But once we get there, what will the transition to AVs actually look like?

For one thing, passenger cars will likely be one of the last vehicle types to see widespread autonomous adoption. Long-haul trucking will probably be the first sector, followed by deliveries. When you finally do step into an AV, it will likely be a taxi or a rental car. (Rental car companies lose a lot of money every year to driver-caused accidents, so they’re eager to transition to an AV fleet that is—at least in theory—less accident-prone.)

As AVs become more common, we’re going to have to rethink many of the systems we’ve created to support driving. Car insurance is a great example. Who is responsible when an autonomous vehicle gets in an accident, the person riding in the car or the company that programmed the software? Governments will have to create new laws and regulations. Roads might even have to change. A lot of highways have high-occupancy lanes to encourage carpooling—will we one day have “autonomous vehicles only” lanes? Will AVs eventually become so popular that you have to use the “human drivers only” lane if you want to be behind the wheel?

That type of shift is likely decades away, if it happens at all. Even once the technology is perfected, people might not feel comfortable riding in a car without a steering wheel at first. But I believe the benefits will convince them. AVs will eventually become cheaper than regular vehicles. And if you commute by car like me, just think about how much time you waste driving. You could instead catch up on emails, or read a good book, or watch the new episode of your favorite show—all things that are possible in fully autonomous vehicles. More importantly, AVs will help create more equity for the elderly and people with disabilities by providing them with more transportation options. And they’ll even help us avoid a climate disaster, since the majority in development are also electric vehicles.

Humanity has adapted to new modes of transportation before. I believe we will do it again. For most of our existence, we relied on natural ways of getting around: We walked, or rode on horseback, or traveled in a boat pushed by wind. Then, in the 1700s, we entered the locomotion age when mobility was powered by steam engines and internal combustion. Now, we find ourselves in the early days of the autonomous age. It’s an exciting time, and I can’t wait to see what new possibilities it unlocks.

The last chapter

My new deadline: 20 years to give away virtually all my wealth

During the first 25 years of the Gates Foundation, we gave away more than $100 billion. Over the next two decades, we will double our giving.

When I first began thinking about how to give away my wealth, I did what I always do when I start a new project: I read a lot of books. I read books about great philanthropists and their foundations to inform my decisions about how exactly to give back. And I read books about global health to help me better understand the problems I wanted to solve.

One of the best things I read was an 1889 essay by Andrew Carnegie called The Gospel of Wealth. It makes the case that the wealthy have a responsibility to return their resources to society, a radical idea at the time that laid the groundwork for philanthropy as we know it today.

In the essay’s most famous line, Carnegie argues that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” I have spent a lot of time thinking about that quote lately. People will say a lot of things about me when I die, but I am determined that "he died rich" will not be one of them. There are too many urgent problems to solve for me to hold onto resources that could be used to help people.

That is why I have decided to give my money back to society much faster than I had originally planned. I will give away virtually all my wealth through the Gates Foundation over the next 20 years to the cause of saving and improving lives around the world. And on December 31, 2045, the foundation will close its doors permanently.

This is a change from our original plans. When Melinda and I started the Gates Foundation in 2000, we included a clause in the foundation’s very first charter: The organization would sunset several decades after our deaths. A few years ago, I began to rethink that approach. More recently, with the input from our board, I now believe we can achieve the foundation’s goals on a shorter timeline, especially if we double down on key investments and provide more certainty to our partners.

During the first 25 years of the Gates Foundation—powered in part by the generosity of Warren Buffett—we gave away more than $100 billion. Over the next two decades, we will double our giving. The exact amount will depend on the markets and inflation, but I expect the foundation will spend more than $200 billion between now and 2045. This figure includes the balance of the endowment and my future contributions.

This decision comes at a moment of reflection for me. In addition to celebrating the foundation’s 25th anniversary, this year also marks several other milestones: It would have been the year my dad, who helped me start the foundation, turned 100; Microsoft is turning 50; and I turn 70 in October.

This means that I have officially reached an age when many people are retired. While I respect anyone’s decision to spend their days playing pickleball, that life isn’t quite for me—at least not full time. I’m lucky to wake up every day energized to go to work. And I look forward to filling my days with strategy reviews, meetings with partners, and learning trips for as long as I can.

The Gates Foundation’s mission remains rooted in the idea that where you are born should not determine your opportunities. I am excited to see how our next chapter continues to move the world closer to a future where everyone everywhere has the chance to live a healthy and productive life.

Planning for the next 20 years

I am deeply proud of what we have accomplished in our first 25 years.

We were central to the creation of Gavi and the Global Fund, both of which transformed the way the world procures and delivers lifesaving tools like vaccines and anti-retrovirals. Together, these two groups have saved more than 80 million lives so far. Along with Rotary International, we have been a key partner in reviving the effort to eradicate polio. We supported the creation of a new vaccine for rotavirus that has helped reduce the number of children who die from diarrhea each year by 75 percent. Every step of the way, we brought together other foundations, non-profits, governments, multilateral agencies, and the private sector as partners to solve big problems—as we will continue to do for the next twenty years.

Over the next twenty years, the Gates Foundation will aim to save and improve as many lives as possible. By accelerating our giving, my hope is we can put the world on a path to ending preventable deaths of moms and babies and lifting millions of people out of poverty. I believe we can leave the next generation better off and better prepared to fight the next set of challenges.

The work of making the world better is and always has been a group effort. I am proud of everything the foundation accomplished during its first 25 years, but I also know that none of it would have been possible without fantastic partners.

Progress depends on so many people around the globe: Brilliant scientists who discover new breakthroughs. Private companies that step up to develop life-saving tools and medicines. Other philanthropists whose generosity fuels progress. Healthcare workers who make sure innovations get to the people who need them. Governments, nonprofits, and multilateral organizations that build new systems to bring solutions to scale. Each part plays an essential role in driving the world forward, and it is an honor to support their efforts.

Of course, although the Gates Foundation is by far the most significant piece of my giving, it is not the only way I give back. I have invested considerable time and money into both energy innovation and Alzheimer’s R&D. Today’s announcement does not change my approach to those areas.

Expanding access to affordable energy is essential to building a future where every person can both survive and thrive. The bulk of my spending in this area is through Breakthrough Energy, which invests in companies with promising ideas to generate more energy while reducing emissions. I also started a company called TerraPower to bring safe, clean, next-generation nuclear technology to life. Both of these ventures will earn profits if successful, and I will reinvest any money I make through them back in the foundation, as I already do today.

I support a number of efforts to fight Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias. Alzheimer’s is a growing crisis here in the United States, and as life expectancies go up, it threatens to become a massive burden to both families and healthcare systems around the world. Fortunately, scientists are currently making amazing progress to slow and even stop the progress of this disease. I expect to keep supporting their efforts as long as it’s necessary.

The success in both areas will determine exactly how much money is given to the foundation since any profits they earn will be part of my overall gift.

What the Gates Foundation hopes to accomplish

Over the next twenty years, the foundation will work together with our partners to make as much progress towards our vision of a more equitable world as possible.

The truth is, there have never been more opportunities to help people live healthier, more prosperous lives. Advances in technology are happening faster than ever, especially with artificial intelligence on the rise. Even with all the challenges that the world faces, I’m optimistic about our ability to make progress—because each breakthrough is yet another chance to make someone’s life better.

Over the next twenty years, the foundation’s funding will be guided by three key aspirations:

In 1990, 12 million children under the age of 5 died. By 2019, that number had fallen to 5 million. I believe the world possesses the knowledge to cut that figure in half again and get even closer to ending all preventable child deaths.

We now understand the essential role nutrition—and especially the gut microbiome—plays in not only helping kids survive but thrive. We’ve made huge advances in maternal health, making sure that new and expectant mothers have the support they need to deliver healthy babies. We have new, life-saving vaccines and medicines, and we know how to get them to the people who need them most thanks to organizations like Gavi and the Global Fund. The innovation is there, the ability to measure progress is stronger than ever, and the world has the tools it needs to put all children on a good path.

Today, the list of human diseases the world has eradicated has just one entry: smallpox. Within the next couple years, I expect to add polio and Guinea worm to the list. (When we eradicate the latter, it will be a testament to the late President Jimmy Carter’s leadership.) I’m optimistic that, by the time the foundation shuts down, we can also add malaria and measles. Malaria is particularly tricky, but we’ve got lots of new tools in the pipeline, including ways of reducing mosquito populations. That is probably the key tool that, as it gets perfected and approved and rolled out, gives us a chance to eradicate malaria.

In 2000, the year that we started the foundation, 1.8 million people died from HIV/AIDS. By 2023, advances in treatment and preventatives cut that number to 630,000. I believe that figure will be reduced dramatically in the decades ahead, thanks to incredible new innovations in the pipeline—including a single-shot gene therapy that could reduce the amount of virus in your body so much that it effectively cures you. This would be massively beneficial to anybody who has HIV, including in the rich world. The same technology is also being used to treat sickle cell disease, an excruciating and deadly illness.

We’re also making huge progress on tuberculosis, which still kills more people than malaria and HIV/AIDS combined. Last year, a historic phase 3 trial began that could be the first new TB vaccine in over 100 years.

The key to maximizing the impacts of these innovations will be lowering their costs to make them affordable everywhere, and I expect the Gates Foundation will play a big role in making that happen. Health inequities are the reason the Gates Foundation exists. And the true test of our success will be whether we can ensure these life-saving interventions reach the people who need them most—particularly in Africa, South Asia, and across the Global South.

To reach their full potential, people need access to opportunity. That’s why our foundation focuses on more than just health.

Education is key. Frustratingly, progress in education is less dramatic than in health—there is no vaccine to improve the school system—but improving education remains our foundation’s top priority in the United States. Our focus is on helping public schools ensure that all students can get ahead—especially those who typically face the greatest barriers, including Black and Latino students, and children from low-income backgrounds. At the K-12 level, that means boosting math instruction and ensuring teachers have the training and support they need—including access to new AI tools that allow them to focus on what matters most in the classroom. Given the importance of a post-secondary degree or credential for success nowadays, we’re funding initiatives to increase graduation rates, too.

As I mentioned, having access to a high-quality nutrition source is key to keeping kids’ development on track. Smallholder farmers form the backbones of local economies and food supplies, and they play a key role in making that happen. One of the main ways the foundation helps farmers is through the development of new, more resilient seeds that yield more crops even under difficult conditions. This work is even more important in a warming world, since no one suffers more from climate change than farmers who live near the equator. Despite that, I’m hopeful that we can help make smallholder farmers more productive than ever over the next two decades. Some of the crops our partners are developing even contain more nutrients—a win-win for both climate adaptation and preventing malnutrition.

We’ll also continue supporting digital public infrastructure, so more people have access to the financial and social services that foster inclusive economies and open, competitive markets. And we’ll continue supporting new uses of artificial intelligence, which can accelerate the quality and reach of services from health to education to agriculture.

Underpinning all our work—on health, agriculture, education, and beyond—is a focus on gender equality. Half the world’s smallholder farmers are women, and women stand to gain the most when they have access to education, health care, and financial services. Left to their own devices, systems often leave women behind. But done right, they can help women lift up their families and their communities.

The United States, United Kingdom, France, and other countries around the world are cutting their aid budgets by tens of billions of dollars. And no philanthropic organization—even one the size of the Gates Foundation—can make up the gulf in funding that’s emerging right now. The reality is, we will not eradicate polio without funding from the United States.

While it's been amazing to see African governments step up, it’s still not enough, especially at a moment when many African countries are spending so much money servicing their debts that they cannot invest in the health of their own people—a vicious cycle that makes economic growth impossible.

It's unclear whether the world’s richest countries will continue to stand up for its poorest people. But the one thing we can guarantee is that, in all of our work, the Gates Foundation will support efforts to help people and countries pull themselves out of poverty. There are just too many opportunities to lift people up for us not to take them.

The last chapter of my career

Next week, I will participate in the foundation’s annual employee meeting, which is always one of my favorite days of the year. Although it’s been many years since I left Microsoft, I am still a CEO at heart, and I don’t make any decisions about my money without considering the impact.

I feel confident putting the remainder of my wealth into the Gates Foundation, because I know how brilliant and dedicated the people responsible for using that money are—and I can’t wait to celebrate them.

I'm inspired by my colleagues at the foundation, many of whom have foregone more lucrative careers in the private sector to use their talents for the greater good. They possess what Andrew Carnegie called “precious generosity,” and the world is better off for it.

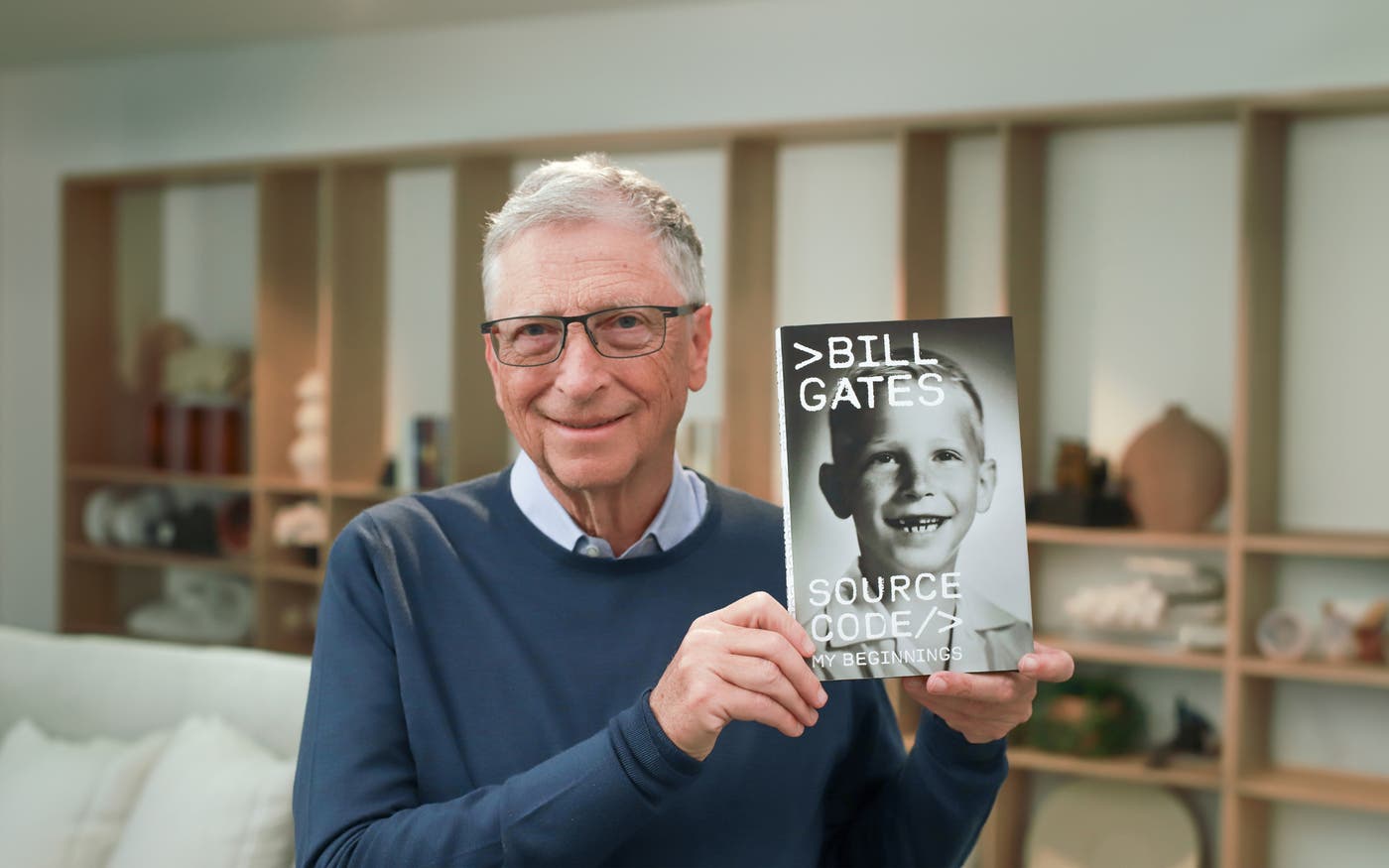

I am lucky to have been surrounded by many generous people throughout my life. As I wrote in my memoir Source Code, my parents were my first and biggest influences. My mom introduced me to the idea of giving back. She was a big believer in the idea of “to whom much is given much is expected,” and she taught me that I was just a steward of any wealth I gained.

Dad was a giant in every sense of the word, and he, more than anyone else, shaped the values of the foundation as its first leader. He was collaborative, judicious, and serious about learning—three qualities that shape our approach to everything we do. Every year, the most important internal recognition we hand out is called the Bill Sr. Award, which goes to the staff member who most exemplifies the values that he stood for. Everything we have accomplished—and will accomplish—is a testament to his vision of a better world.

As an adult, one of my biggest influences has been Warren Buffett, who remains the ultimate model of generosity. He was the first one who introduced me to the idea of giving everything away, and he’s been incredibly generous to the foundation over the decades. Chuck Feeney remains a big hero of mine, and his philosophy of “giving while living” has shaped how I think about philanthropy.

I hope other wealthy people consider how much they can accelerate progress for the world’s poorest if they increased the pace and scale of their giving, because it is such a profoundly impactful way to give back to society. I feel fulfilled every day I go to work at the foundation. It forces me to learn new things, and I get to work with incredible people out in the field who really understand how to maximize the impact of new tools.

Today’s announcement almost certainly marks the beginning of the last chapter of my career, and I’m okay with that. I have come a long way since I was just a kid starting a software company with my friend from middle school. As Microsoft turns 50 years old, it feels right that I celebrate the milestone by committing to give away the resources I earned through the company.

A lot can happen over the course of twenty years. I want to make sure the world moves forward during that time. The clock starts now—and I can’t wait to make the most of it.

Speaking up

The day I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life

How giving a speech helped me decide to focus on philanthropy.

Part 1 of the Netflix documentary series Inside Bill’s Brain tells the story of the Gates Foundation’s quest to rethink sanitation for the world’s poorest. First step: reinvent the toilet! This belief in the power of innovation has been a constant in my life, starting from the time I fell in love with software in high school to my work today at our foundation. What follows is the story of a moment of clarity for me on that path and the influence of someone who’s been a critical guide along the way.

If you’d have asked me in my twenties if I’d ever retire early from Microsoft, I’d have told you that you were crazy. I loved the magic of software, and the ever-rising learning curve that Microsoft provided. It was hard for me to imagine anything else I’d rather do.

By my mid-forties my perspective was changing. The U.S. government’s antitrust suit against Microsoft had drained me, sucking some of the joy out of my work. Stepping down as CEO in early 2000, I hoped to focus more on building software products, always the best part of my job.

Also, my world view was broadening. Both Melinda and I were feeling a strengthening pull toward our young foundation and its work in U.S. education and the development of drugs and vaccines for diseases in poor countries. For the first time in my adult life I allowed myself space for non-Microsoft reading, soaking up books on the immune system, malaria and the history of plagues just as I had once scoured The Art of Computer Programming.

With our commitment to philanthropy growing, Melinda and I transferred $20 billion of Microsoft stock to our foundation, making it the largest of its kind in the world. Within a year I’d taken my first overseas trip for the foundation, to India, where I squeezed drops of polio vaccine into babies’ mouths. Melinda traveled to Thailand and India to study how those countries were handling AIDS.

Our good friend Warren Buffett was curious about this new journey we were on. So in the fall of 2001, he invited me to a resort in West Virginia and asked me to speak to a group of business leaders about what Melinda and I were learning.

I’m not a natural public speaker. But at Microsoft, speech after speech, year after year, I learned to step out on a stage and paint a vision of technology for our customers, partners and the media. It helped that people wanted to hear about the white-hot software industry. I grew to enjoy it.

I felt like I was starting over with our foundation. At big global meetings, like the World Economic Forum, people flocked to hear me detail some cool piece of software, but the crowd and the energy would be gone when later that day I’d announce an innovative plan to get vaccines to millions of children.

At the time, many people I met thought health problems in low-income countries were so big and intractable that no amount of money could make any significant difference. I could see why. It was easy to ignore death and disease happening so far away. And so much of what we read in the news about global health focused on doom and gloom. This frustrated me. The problems were real enough, but so is the power of human ingenuity to find solutions. Melinda and I felt a strong sense of optimism, but we didn’t see that reflected in these stories.

Right around the time Warren asked me to give the talk, Melinda and I were trying to figure out how we might use our voices to raise the visibility of global health. Would anyone listen?

My speech to Warren’s friends was a chance to practice. If I could stir them, it would be a step towards persuading the people with the power to make the biggest difference: the legislators and heads of countries who decide how much money flows into foreign aid and global health.

I was a little nervous heading to the conference room where Warren’s group was gathered—but more than that, I was exhausted. We were in the midst of negotiations over the antitrust case, and I’d been on the phone with lawyers deep into the night. I hadn’t had time to write a full speech. I’d just jotted notes between calls, trying to simplify all we had learned into the clearest possible story.

I started talking, haltingly at first. Our big revelation, I explained, had come in the mid-1990s when Melinda and I realized how much misery in poor countries is caused by health problems that the rich world had stopped trying to solve because we’re no longer affected by them. That incensed us. The cost of that inequity at the time was three million children dying ever year, I said.

Those deaths, we realized, weren’t caused by a bunch of runaway diseases, but by a handful of illnesses that are largely treatable. Diarrhea and pneumonia alone were responsible for half of the deaths among children. Many of those children could be saved with medicines and vaccines that already existed. All that was lacking were incentives and systems to get those life-saving technologies to the people and places where they were needed—and some new inventions to speed the change.

Our philanthropy, I explained, followed the same philosophy that guided Microsoft: relentless innovation. The right vaccine can wipe a deadly virus off the planet. A better toilet can help stop diarrheal disease. Investments in science and technology can help millions to survive their childhood and lead healthy productive lives—potentially the greatest return in R&D spending ever.

As I spoke, the legal tangles that had consumed me the night before vanished. I was energized. When ideas excite me, I rock, I sway, I pace—my body turns into a metronome for my brain. For the first time, all the facts and figures, anecdotes and analyses cohered into a story that was uplifting—even for me. I was able to make clear the logic of our giving and why I was so optimistic that a combination of money, technology, scientific breakthroughs, and political will could make a more equitable world faster than a lot of people thought.

I could tell from the nods and laughs and caliber of questions that the group got it. Afterward, Warren came over with a big smile. “That was amazing, Bill,” he said. “What you said was amazing, and your energy around this work is amazing.” I grinned back at him. Three ‘amazings’—a first.

The confidence I found that day encouraged me to take a more public role on global health issues. Over the next year, I refined my message at events and in interviews. I spent more time talking about health with government leaders. (That’s now a big part of my job.)

But something else had happened, too. The speech helped me see more clearly a life for myself after Microsoft, centered on the work that Melinda and I had started. Software would remain my focus for years and I will always consider it the thing that most shaped who I am. But I felt energized to get further along this new path we were traveling, to learn more and to apply myself to the obstacles in the way of more people living better lives. Eventually, I would retire from Microsoft almost a decade earlier that I had planned. The 2001 speech was a step, a private moment, on the way to that decision.

Now I get to focus every day on trying to deliver the vision I outlined in that conference room almost two decades ago. The world is more equitable now than it was then. But we’ve still got a long way to go. By letting Netflix’s cameras in, I hope you can see the joy I get from my work and why I am so optimistic that with ingenuity, imagination, and determination, we can make even more progress towards that goal.

Rewards Offered

The most gratifying job on Earth

Where can you make the biggest impact with your giving?

I grew up in a family where giving back to society—whether through volunteer time or financial resources—was just part of what you did. At the dinner table, both of my parents talked frequently about their volunteer work with non-profits and their advocacy work for children and the less fortunate in our community.

Community service was also an important part of Melinda’s upbringing; so even when we were still just engaged to be married, we talked about our responsibility to give back the great majority of our wealth—even though at that point we didn’t know exactly how or when we’d do it.

Anyone who wants to seriously engage in giving faces two important questions: where can you make the biggest impact, and how do you structure your giving so it’s effective.

Our viewpoint evolved over time, but there was a real turning point when we read an article about rotavirus, a disease that was pretty much a non-event in the United States, but which still killed a half-million children a year in the developing world. It seemed impossible to us that it was receiving so little worldwide attention. And so we dug in, learnt a lot more about the problem, and eventually began a serious effort to reduce childhood mortality worldwide.

Today, the framework that guides our giving is based on the simple premise that everyone deserves the chance to live a healthy, productive life. Given the resources at our disposal, we believed we could make the biggest difference by concentrating in three areas: global health, global development, and in the US, education.

Half our foundation’s funds are spent addressing global health problems, with a focus on malaria, tuberculosis, AIDS, diarrheal and respiratory diseases.

Twenty-five per cent of the foundation’s funds assist the poorest people in the world in ways other than healthcare through development projects. And the other 25% is devoted to improving public education in the US, where, in spite of our nation’s great wealth, our education system continues to fail too many of our children.

A few basic principles guide the way in which we give. Our approach emphasizes partnerships, and looks to foster innovation, often pursuing new technologies or delivery schemes.

We try to apply new thinking and approaches to solving big problems, which sometimes means taking calculated risks on promising ideas. We set goals and are quite serious about measuring our results. Often, this means attempting to be a catalyst by investing in areas where governments can’t or won’t invest, or where there is a vacuum or failure in the marketplace.

Diseases that affect the poor are a great case in point. Rich-world diseases attract research investments that dwarf the money going to problems like rotavirus. (Think of how much more money goes to curing male pattern baldness than malaria!) As a foundation, we have the chance to help address that inequality.

The question of risk is something we think about a lot. Warren Buffett, our good friend and the third trustee of our foundation, reminds us that failure will be part of any bold approach. “You can have a perfect batting average by not doing anything too important. Or you’ll bat something less than that if you take on the really tough problems.”

We’re willing to accept failure at times in the name of trying new things to solve old and difficult problems.

At the end of the day, what draws people to philanthropy is something universal—the connection to other human beings and the desire to make a difference. This is what tugs at people and that makes them want to get involved, to imagine how they can help create a better world.

For me, philanthropy is a responsibility, a passion, and an honor. And so far as I can tell—after being a parent—it’s the most gratifying job on earth.

Note – An edited version of this post was published as part of the ‘Doing Good’ series on livemint.com.

Meeting the needs

By 2026, the Gates Foundation aims to spend $9 billion a year

COVID created huge needs around the world. Here’s how we will help.

Several huge global setbacks over the past few years have left many people discouraged and wondering whether the world is destined to keep getting worse. The pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine are just two examples. These setbacks are causing significant suffering.

But it is important to remember that they are happening in the context of two decades’ worth of historic progress. I believe it is possible to mitigate the damage and get back to the progress the world was making. In this post I will enumerate the progress and the setbacks, explain how the world can respond, and discuss how I and others can do our part.

Melinda and I started our foundation in 2000 to advance our vision that every person should have the chance to live a healthy and productive life. That same year, the world set an ambitious vision for improving people’s lives when it adopted the United Nations Millennium Development Goals and agreed to measurable targets for meeting those goals.

Over the next 20 years—thanks to efforts by governments, the private sector, non-profits, and philanthropies like ours—the number of children who died before their fifth birthday dropped by half, from 12 million per year to 6 million per year. The fraction of people living in extreme poverty also dropped by half. More children enrolled in school than ever. Deadly diseases such as HIV, TB, and malaria went into retreat, as the number of people who died from these diseases continued to fall. This progress was not limited to one region or to wealthy countries. It happened in dozens of countries all over the world from Bangladesh to Ethiopia to Ghana.

Against this backdrop, the pandemic is one of the biggest setbacks in history. The world was poorly prepared, so the damage is widespread. In addition to more than 20 million excess deaths caused by COVID— exacerbated by the inequity in vaccine distribution between high- and low-income countries—childhood deaths from all causes are going up because of disruptions to health systems. Polio eradication was set back several years. Students have lost as many as two years of learning in most countries. Emergency spending on the COVID response has left governments with large debts that will have to be paid off. Many countries are experiencing significant job losses, particularly among women. Women have had to bear most of the burden of taking care of children who were not in school.

The war on Ukraine is a gigantic tragedy for the entire world. Ukraine itself is experiencing the death and destruction of an intense war. The country will have to be rebuilt. The reduction in the supply of natural gas is driving up costs, such as the cost of electricity, particularly in Europe. The reduction in the supply of food—particularly wheat and edible oils—and the supply of fertilizer is driving up food prices, which will increase malnutrition and instability in low-income countries.

The world economy is entering a low-growth cycle, with rising interest rates and high inflation. Deficit spending will have to be reined in to reduce inflationary pressure. Government income will go down and more will be spent on interest payments, which will reduce the amount of money available for programs and make trade-offs necessary. Aid budgets will be stretched, and the poorest countries may see support cut at the time when they need it most. Many low- and middle-income countries have unsustainable levels of debt, particularly as their currencies weaken against the currencies they have borrowed in. Reducing these debts will be particularly hard because a significant portion of them is owed to China and the private sector, rather than traditional development banks, which makes it much more challenging to negotiate debt relief.

The damage from climate change is already worse than most models predicted. We are seeing a lot of bad weather events, including heat waves and lower agricultural output, particularly in countries near the Equator. Most countries are falling short of the climate commitments they have made. Hard-to-reduce emissions from agriculture/deforestation, buildings, and industrial production including cement and steel continue to go up, more than offsetting the reductions from electric cars and renewable energy. Low-income countries are hurt the most, even though they are responsible for only a small portion of the historical emissions.

We are facing all these global crises at a time of deep political polarization in the United States. The political divide limits our political capacity for dialogue, compromise, and cooperation and thwarts the bold leadership required both domestically and internationally to tackle these threats. Polarization is forcing us to look backwards and fight again for basic human rights, social justice, and democratic norms. I believe the reversal of abortion rights in the U.S. is a huge setback for gender equality, for women’s health, and for overall human progress. The potential for even further regression is scary. It will put lives at risk for women, people of color, and anyone living on the margins.

Response to setbacks

How can I possibly still be optimistic? I see incredible heroism and sacrifice all over the world. Medical workers put in unbelievable hours at great risk to themselves to help people infected with COVID. Incredible efforts are taking place to help refugees from the Ukrainian war and to help those caught in battle zones. Activists are courageously protesting and often risking their lives to protect people’s rights. People on the front lines inspire me to do whatever I can. Although each of us can only do so much, when lots of people join in we will resume progress.

We need all sectors of society—government, the private sector, and the non-profit sector including philanthropy—to engage on these issues. Philanthropy is the smallest of these sectors, but it is unique in its ability to try risky ideas that can have a large impact if they succeed and are scaled up.

I wish I knew how to help bring the war to a quicker end or to shorten the economic downcycle or improve our political capacity. I have an open mind to helping anyone who proposes how to improve these areas.

Personally, I am putting a lot of my energy and resources into innovators working on pandemic prevention, global health, climate mitigation (including getting rid of dependence on hydrocarbons) and adaptation, education improvement (including remediation), and food costs. When I say “innovation,” I’m referring to new products and services as well as new ways of delivering them to those in need—including by strengthening local leaders and institutions. These innovations will not come in time to avoid the problems altogether, but the faster we move, the less people will suffer. For many people including myself this is the most concrete way of contributing, even when it seems modest compared to the scale of the problems. Focusing on being part of the solution is better than giving up in despair.

Innovation areas

These are some of the areas where I think innovation can make a big difference with new tools and new ways of delivering them. These are areas where the groups I am involved with—the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Breakthrough Energy (for climate mitigation)—are working with partners to come up with solutions, and the innovations I describe are all in the pipeline.

Preventing pandemics. Eventually, we will have vaccines that prevent infection (as opposed to reducing only the risk of getting severely ill or dying) and last for at least a decade. A vaccine that prevented infection would cut cases over half in countries with good vaccine coverage. (These vaccine advances will also allow scientists to make vaccines for TB and HIV.) A drug that blocks respiratory infection will be able to be deployed even faster than a new vaccine. The world should fund and staff a global group connected to the WHO doing monitoring so that outbreaks are stopped before they become pandemics.

Reducing childhood deaths. The world can get back to and even exceed the vaccine coverage levels we had before the pandemic, when 80 percent of children were being reached. There will be new vaccines for respiratory diseases and other conditions that threaten the lives of infants and children in low-income countries. A new generation of malaria-preventing bednets will help overcome the resistance that mosquitos have developed to the current generation. Researchers need to invent transformative tools, including more-effective vaccines and new ways of reducing mosquito populations to allow for eventually eradicating malaria. Because of COVID and other setbacks, the United Nations’ goal to cut childhood deaths in half again to 3 million by 2030 will be missed, but it can still be achieved the following decade.

Eradicating diseases. Polio is nearly eradicated—the number of cases has dropped 99.9 percent since 1988. Some countries have recently benefited from innovations such as better mapping capabilities to make sure that all children are reached with vaccines. Mobile money is being used to make sure vaccinators get paid. An improved polio vaccine was given an emergency license during the pandemic and is now being used in 20 countries. The last places with endemic cases of wild polio are Pakistan and Afghanistan, and with the right level of funding and stability, eradication has a strong chance of succeeding in 3 to 4 years—which will make it only the second disease after smallpox to be eradicated. Recent cases in Malawi and Mozambique—after decades with no wild polio—and recent detection of poliovirus in sewage in London remind us that it will spread back globally if we don’t get rid of it completely.

Improving food security and climate adaptation. Low- and middle-income countries are already by far the most affected by climate change, given that they depend on agriculture that is being put at risk by more frequent droughts and floods. Africa is currently a large net importer of food, including grains and edible oils. More than 30 percent of African and South Asian children are so malnourished that they don’t fully develop their mental and physical potential. With population growth and climate change, Africa will have less food per person unless agricultural productivity is increased. A new generation of seeds along with using cell phones to advise farmers on better farming practices will allow a doubling of agricultural productivity in Africa despite climate change. This will turn Africa from a net food importer to a net food exporter and reduce pressure to deforest. This is an important piece of climate adaptation that requires far more investment.

Achieving gender equality. Melinda has helped me and many others see how improving women’s access to health care and contraceptives, empowering girls with better education, giving women access to savings and credit, and creating leadership opportunities for them can lift up societies. This is not only an equity issue but a way of making progress for everyone. There is still a lot to do in improving maternal health and providing access to family planning, especially for women in low- and middle-income countries. Innovations include better contraceptive choices, new ways of reducing anemia, and inexpensive tools for reducing maternal mortality. Increasing the use of mobile phones by women can create economic opportunities for them and give them access to digital financial services.

Improving educational outcomes. Just equipping students with computers only improves education outcomes modestly. By adding personalized, engaging curriculum and systems to detect when students need advice and support, the foundation’s partners have seen substantial gains. This work covers everything from structured pedagogy in lower-income countries to improving math instruction in the American K-12 system to preparation for key classes in college. Getting this right has turned out to be far harder than I expected, but it is clearly achievable.

Mitigating climate change. We can invent new ways of making products that eliminate emissions while not costing much more. I call this reducing the Green Premiums, and the toughest areas include making zero-emissions steel and cement. Several companies funded by my Breakthrough Energy group and others in the past few years have made more progress than I expected. Policies in rich countries can drive demand for these products, helping to bring the Green Premiums down to zero. It is still daunting since it requires replacing large parts of the physical economy in all the high- and middle-income countries. As more people witness the progress here, I think a sense of real possibility will emerge, which will help get the policies and urgent action necessary to succeed.

I am very proud of the Gates Foundation’s role in these areas. (I fund climate mitigation through Breakthrough Energy, not the foundation.) We have been able to help bring together other foundations, non-profits, governments, multilateral agencies, and the private sector as partners to solve big problems. We were central to the creation of GAVI and the Global Fund, both of which created innovative ways to deliver lifesaving tools like vaccines and anti-retrovirals to people who need them most. Together these two groups have saved 60 million lives so far. Along with Rotary International, we have been a key partner in reviving the effort to eradicate polio. We supported the creation of a new vaccine for rotavirus that has reduced the number of children who die of this disease every year by 75 percent, from 528,000 annually in 2000 to 128,500 in 2016. And we are just at the beginning of the work that is needed to ensure that women have the access and power to use these innovations.

Accelerating investment

Over the past two decades, the Gates Foundation has gone from spending around $1 billion per year to spending nearly $6 billion per year. During the pandemic, Melinda and I approved spending an additional $2 billion so we could help with the COVID response without taking money away from other important work that we fund. (Of this commitment, $1.5 billion had been spent by the end of 2021, with remaining commitments of up to $500 million that have not been disbursed.) At the time, we expected the extra spending to stop once the acute phase of the pandemic was over. But it is now clear that the need in all the areas where we work is greater than ever. The great crises of our time require all of us to do more.

For this reason, rather than returning the foundation’s budget to pre-pandemic levels, we will continue to expand it. With the support and guidance of our board, the Gates Foundation intends to increase spending from nearly $6 billion per year before COVID to $9 billion per year by 2026. Our focus will remain the same—but at this moment of great need and opportunity, this spending will allow us to accelerate progress by investing more deeply in the areas where we are already working. To help make this spending increase possible, I am transferring $20 billion to the foundation’s endowment this month.

Biggest gift ever given

There is one not-very-well-known but incredibly important reason why the foundation has been able to be so ambitious. Although it is named the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, basically half of our resources to date have come from Warren Buffett’s gifts. Since 2006, Warren has gifted the foundation $35.7 billion, including his most recent gift of $3.1 billion in June. The actual value of these gifts is about $45 billion if you include the appreciation of the Berkshire Hathaway stock after it was given. Warren’s advice and thinking influenced the foundation in a profound way even before he made any gifts. Warren, I can never adequately express how much I appreciate your friendship and guidance as well as your generosity.

Future plan

As I look to the future, my plan is to give all my wealth to the foundation other than what I spend on myself and my family. I do some giving and investing in U.S. health care issues, including Alzheimer’s, outside the foundation. Through Breakthrough Energy, I will continue to invest and give money to address climate change. Overall I expect that the work in these areas will make money, which will also go to the foundation. I will move down and eventually off of the list of the world’s richest people. My giving this money is not a sacrifice at all. I feel privileged to be involved in tackling these great challenges, I enjoy the work, and I believe I have an obligation to return my resources to society in ways that have the greatest impact for improving lives.

I hope others in positions of great wealth and privilege will step up in this moment too.

Moral center

My fondest memories of Jimmy Carter

He and Rosalynn were among my first and most inspiring role models in global health.

I am deeply saddened to learn of the passing of former president Jimmy Carter, and my heart is heavy for the whole Carter family. For more than two decades, I’ve had a chance to work with Jimmy, Rosalynn, and the Carter Center on several global health efforts, including our mutual work to eliminate deadly and debilitating diseases.

The Carters were among my first and most inspiring role models in global health. Over time, we became good friends. They played a pretty profound role in the early days of the Gates Foundation. I’m especially grateful that they introduced us to Dr. Bill Foege, who once helped eradicate smallpox and was a key advisor for our global health work.

Jimmy and Rosalynn were also good friends to my dad. One of my favorite photographs of all time shows Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela, and my dad in South Africa holding babies at a medical clinic. I remember my dad coming back from that trip with a whole new appreciation for Jimmy’s passion for helping people with HIV. At the time, then-President Thabo Mbeki was refusing to let people with HIV get treatment, and my dad watched Jimmy almost get into a fist fight with Mbeki over the issue. As Jimmy said in a 2012 conversation at the Gates Foundation hosted by my dad, “He was claiming there was no relationship between HIV and AIDS and that the medicines that we were sending in, the antiretroviral medicines, were a white person’s plot to help kill black babies.” At a time when a quarter of all people in South Africa were HIV positive, Jimmy just couldn’t accept Mbeki’s obstructionism.

As with HIV, Jimmy was on the right side of history on many issues. During his childhood in rural Georgia, racial hatred was rampant, but he developed a lifelong commitment to equality and fairness. Whenever I spent time with him, I saw that commitment in action. He had a remarkable internal compass that steered him to pursue justice and equality here in America and around the world.

After Jimmy “involuntarily retired” (his term) from the White House, he reset the bar for how Presidents could use their time and influence after leaving office. When he started the Carter Center, he gave a huge shot in the arm to efforts to treat and cure diseases that rich governments were ignoring, like river blindness and Guinea worm. The latter once devastated an estimated 3.5 million people in Africa and South Asia every year. That total dropped to just 14 cases in 2023, thanks to the incredible efforts of the Carter Center.

When the world eradicates Guinea worm, it will be a testament to Jimmy’s dedication—and yet another remarkable achievement to add to his list of accomplishments. He won the United Nations Human Rights Prize and the Nobel Peace Prize. He wrote 30 books. He helped monitor more than 100 elections in countries with fragile democracies—and did not pull and punches about the ways America’s own democracy was being undermined from within.

He worked to erase the stigma of mental illness and improved access to care for millions of Americans. He taught at Emory University. He built hundreds of homes with Habitat for Humanity. And, as I saw when I visited with Jimmy and Rosalynn in Plains a few years ago, he also painted, built wooden furniture, and took the time to offer his intellect and wisdom to people from all walks of life. As he once told my dad, tongue in cheek, “I have Secret Service protection, so I can pretty well do what I want to!”

Whenever I have struggled with a global health challenge, I knew I could call him and ask for his candid advice. It’s just starting to sink in that I can no longer do that.

But President Carter’s example of moral leadership will inspire me for as long as I’m able to pursue philanthropy—just as it will the hundreds of millions of people whose lives he touched through peacemaking, preaching, teaching, science, and medicine. James Earl Carter Jr. was an incredible statesman and human being. I will miss him dearly.

Goodbye

Remembering my father

I will miss my dad every day.

My dad passed away peacefully at home yesterday, surrounded by his family.

We will miss him more than we can express right now. We are feeling grief but also gratitude. My dad’s passing was not unexpected—he was 94 years old and his health had been declining—so we have all had a long time to reflect on just how lucky we are to have had this amazing man in our lives for so many years. And we are not alone in these feelings. My dad’s wisdom, generosity, empathy, and humility had a huge influence on people around the world.

My sisters, Kristi and Libby, and I are very lucky to have been raised by our mom and dad. They gave us constant encouragement and were always patient with us. I knew their love and support were unconditional, even when we clashed in my teenage years. I am sure that’s one of the reasons why I felt comfortable taking some big risks when I was young, like leaving college to start Microsoft with Paul Allen. I knew they would be in my corner even if I failed.

As I got older, I came to appreciate my dad’s quiet influence on almost everything I have done in life. In Microsoft’s early years, I turned to him at key moments to seek his legal counsel. (Incidentally, my dad played a similar role for Howard Schultz of Starbucks, helping him out at a key juncture in his business life. I suspect there are many others who have similar stories.)

My dad also had a profound influence on my drive. When I was a kid, he wasn’t prescriptive or domineering, and yet he never let me coast along at things I was good at, and he always pushed me to try things I hated or didn’t think I could do (swimming and soccer, for example). And he modeled an amazing work ethic. He was one of the hardest-working and most respected lawyers in Seattle, as well as a major civic leader in our region.

My dad’s influence on our philanthropy was just as big. Throughout my childhood, he and my mom taught me by example what generosity looked like in how they used their time and resources. One night in the 1990s, before we started our foundation, Melinda, Dad, and I were standing in line at the movies. Melinda and I were talking about how we had been getting more requests for donations in the mail. Dad simply said, “Maybe I can help.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation would not be what it is today without my dad. More than anyone else, he shaped the values of the foundation. He was collaborative, judicious, and serious about learning. He was dignified but hated anything that seemed pretentious. (Dad’s given name was William H. Gates II, but he never used the “II”—he thought it sounded stuffy.) He was great at stepping back and seeing the big picture. He was quick to tear up when he saw people suffering in the world. And he would not let any of us forget the people behind the strategies we were discussing.

People who came through the doors of the Gates Foundation felt honored to work with my dad. He saw the best in everyone and made everyone feel special.

We worked together at the foundation not so much as father and son but as friends and colleagues. He and I had always wanted to do something concrete together. When we started doing so in a big way at the foundation, we had no idea how much fun we would have. We only grew closer during more than two decades of working together.

Finally, my dad had a profoundly positive influence on my most important roles—husband and father. When I am at my best, I know it is because of what I learned from my dad about respecting women, honoring individuality, and guiding children’s choices with love and respect.

Dad wrote me a letter on my 50th birthday. It is one of my most prized possessions. In it, he encouraged me to stay curious. He said some very touching things about how much he loved being a father to my sisters and me. “Over time,” he wrote, “I have cautioned you and others about the overuse of the adjective ‘incredible’ to apply to facts that were short of meeting its high standard. This is a word with huge meaning to be used only in extraordinary settings. What I want to say, here, is simply that the experience of being your father has been… incredible.”

I know he would not want me to overuse the word, but there is no danger of doing that now. The experience of being the son of Bill Gates was incredible. People used to ask my dad if he was the real Bill Gates. The truth is, he was everything I try to be. I will miss him every day.

My family worked together on a wonderful obituary for my dad, which you can read here.

…and many more

Happy 90th, Warren!

It’s hard to believe Warren Buffett is entering his tenth decade.

Warren Buffett turns 90 years old today. It’s hard to believe that my close friend is entering his tenth decade. Warren has the mental sharpness of a 30-year-old, the mischievous laugh of a 10-year-old, and the diet of a 6-year-old. He once told me that he looked at the data and discovered that first-graders have the best actuarial odds, so he decided to eat like one. He was only half-joking.

Here’s a short birthday video in honor of his dietary preferences:

Warren is still so youthful that it’s easy to forget he was once an actual young man, just starting out in his career. Here he is with his first wife, Susan, and their first two children, Susie and Howard. (Peter hadn’t been born yet.) This photo was taken in 1956, around the time Warren started the Buffett Partnership, the investment firm that eventually morphed into Berkshire Hathaway.

Upsidedownright

Grilling and chilling with Warren

Learn what Warren Buffett and a Dairy Queen Blizzard have in common.

If you’ve ever been to a Dairy Queen, you’re probably familiar with one of their most popular menu items, the Blizzard, soft serve ice cream mixed with sundae toppings, cookies, brownies, or candy. You might also be aware that every Blizzard is served upside down—a surprising piece of fast food performance art to prove that each treat is so thick it will defy gravity.

“Thinking differently and celebrating an upside-down philosophy runs deep in the DQ system,” is how one Dairy Queen executive once explained the practice.

The same could be said of the genius of Dairy Queen’s owner, Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway empire acquired the restaurant chain in 1998. (A frequent Dairy Queen customer, Warren explained at the time that he and his business partner, Charlie Munger, “put our money where our mouth is.”)

Every time I get to see Warren, I’m struck by his surprising, insightful, “upside-down” view of the world. He thinks differently—about almost everything. For starters, he credits his amazing success to something anyone could do. “I just sit in my office and read all day,” he explained.

In a time when instant gratification is craved in all aspects of life, Warren is one of the most patient people I know, willing to wait to get the results he wants. As he once said, “Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

And, as I’ve learned again and again during my visits with him even his diet is oddly upside down. Instead of ending his day with dessert, that’s how he likes to begin the day. He counts Oreos and ice cream among his breakfast foods!

During my visit to Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting in Omaha last month, I learned more about Warren’s sweet tooth. Warren and I broke away from the meetings to visit a Dairy Queen for some lunch and to get some restaurant training. We learned how to work the cash register, greet guests, and make a Blizzard (including the proper way to serve it, “Always upside down with a smile!”) I think I may have been a quicker study than Warren in the Blizzard department but watch the video above and you can judge for yourself.

Now that Warren knows how to make a Blizzard, I suspect it will be on his breakfast menu too. (Warren, just be careful turning it upside down!)

Sweet emotion

Warren and I visited a fantastic candy store in Omaha

And had a blast.

Whenever I hang out with Warren Buffett, I feel like a kid in a candy store. And not just because of his famous sweet tooth (one of the first times he came to visit in Seattle, our kids were stunned when they saw him chowing down Oreos for breakfast). We’ve been close friends for more than 25 years, and we have just as much fun together now as we did when we first met. In all that time we have never run out of things to talk about and laugh about.

So when we got together in Omaha during this year’s Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, we decided to check out a real candy store. Actually, although the Fairmont Antiques & Mercantile has just about every kind of sweet you can imagine, it is much more than a candy store. It’s also an old-fashioned soda shop, used record store, vintage memorabilia shop, and pinball museum. We had a blast reminiscing about our favorite treats, Melinda’s and my special history with Willie Nelson, why pinball machines were the best business Warren ever had, and a lot more. Take a look:

Berkshire beds

Testing mattresses with Warren Buffett

Our visit to Omaha’s 80-acre furniture store.

When the weather turns warm, some people head to the beach. Some like a picnic in the park. Personally, there is one place I visit every spring no matter what: Omaha, Nebraska, the site of Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholders weekend with the company’s CEO and chairman (and my friend) Warren Buffett.

“Woodstock for Capitalists” is always a magical weekend, and this year’s was no exception. Tens of thousands of people came to buy stuff from Berkshire companies, check out the local steakhouses, and most of all, soak up the wit and wisdom of Warren and his partner, Charlie Munger. I would go even if I weren’t on the company’s board of directors. Despite all the changes in the business landscape during Warren’s 52-year tenure, he has lived by the same principles of integrity and creating business value since day one. He sets a wonderful example, and even though I have known him well for more than 25 years, I have never stopped learning from him.

Although the Berkshire weekend is always busy, Warren and I usually find time to goof off with a few games of bridge or a golf-cart ride around the showroom. (See my posts from 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. I didn’t post anything last year, but we goofed off then too.)

This year, Warren took me on a tour of Nebraska Furniture Mart, a super-successful megastore owned by Berkshire. We tried out some lounge chairs, played with remote-controlled mattresses, and somehow managed to get lost. Take a look:

Starting line

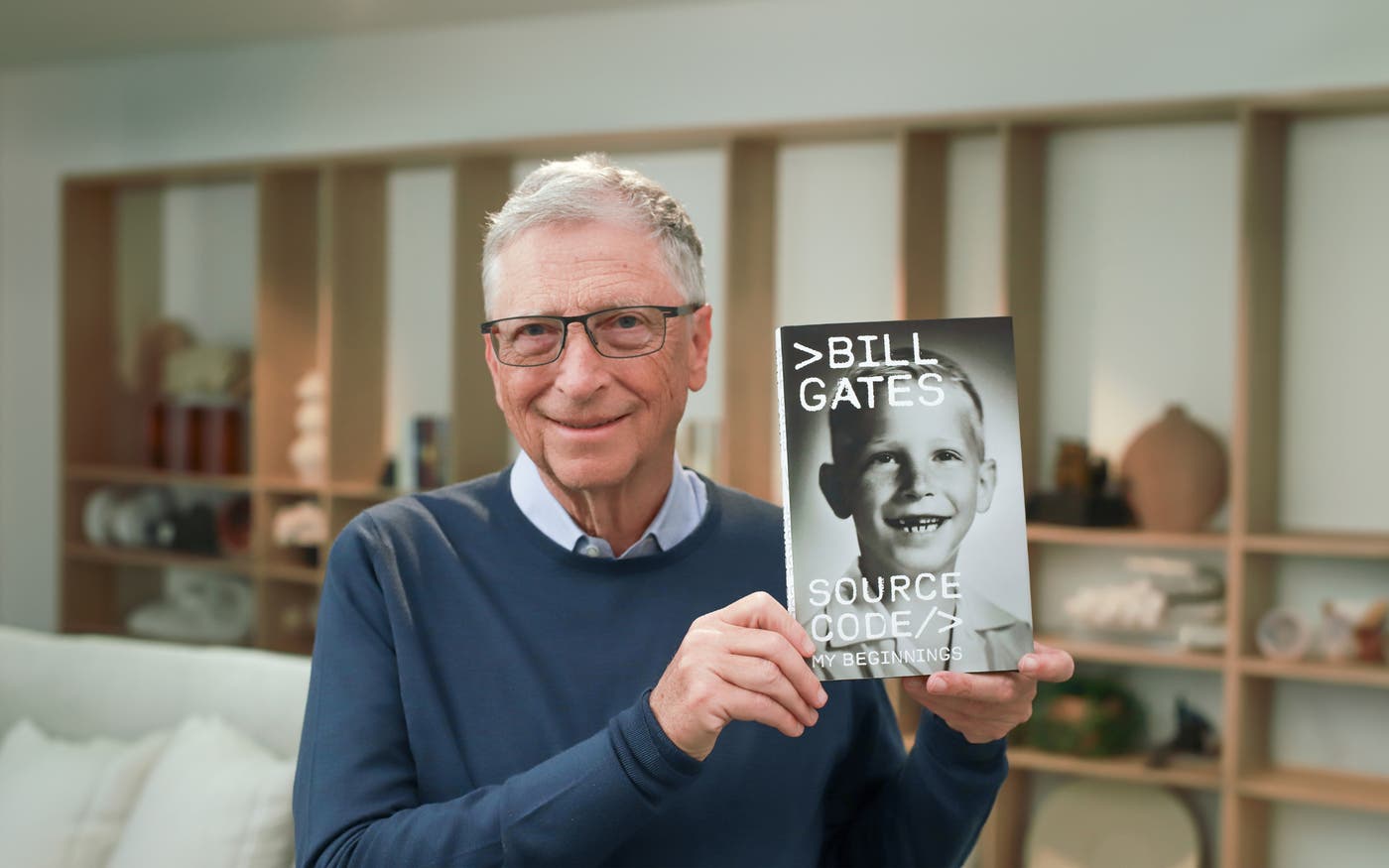

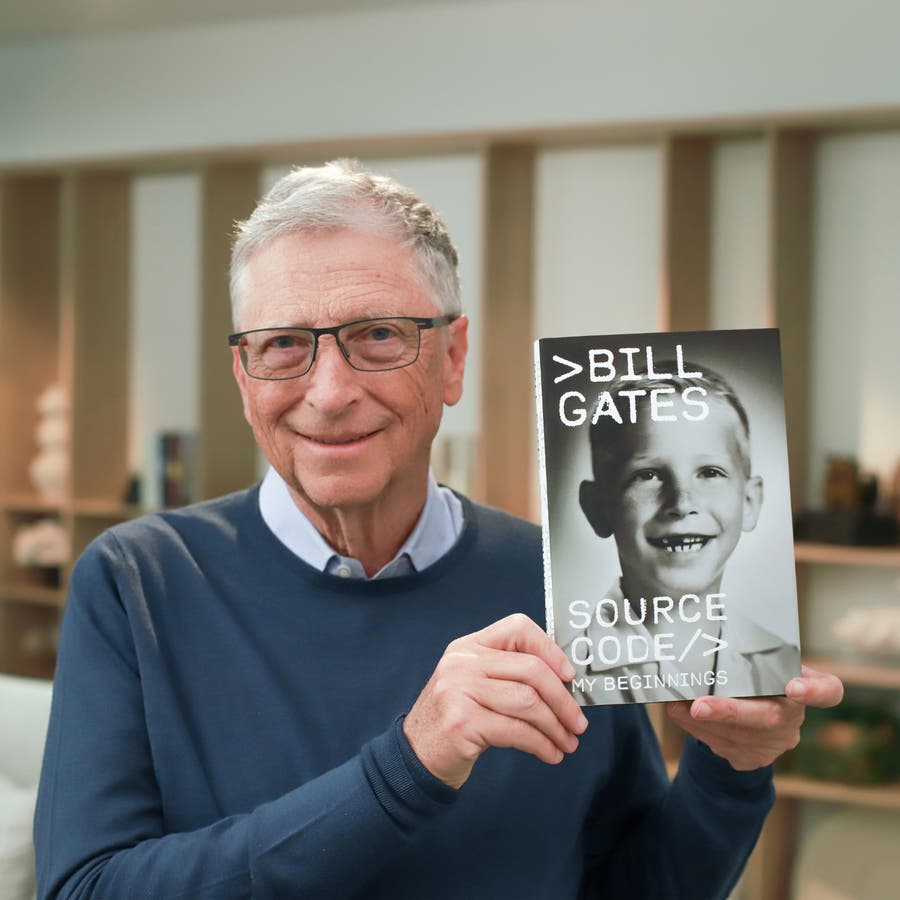

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

Source Code

The brilliant teachers who shaped me

In my new book, I give credit where it’s due.

I was an extremely lucky kid. I was born to great parents who did everything to set me up for success. I grew up in a city I love and still call home, at the dawn of the computer age. And I went to one of two schools in my state—one of a handful in the country—that actually had computer access. These were all strokes of luck that helped shape my future.

But equally important, maybe most important, were the teachers I was fortunate enough to learn from along the way. In my new book, Source Code, I write about many of them. From grade school through college, I had teachers who saw my potential (even when it was buried under bad behavior), gave me real responsibilities, let me learn through experience instead of lectures, and created space for me to explore my passions.

These five brilliant teachers didn’t just teach me subjects; they taught me how to think about the world and what I might accomplish in it. Looking back, I realize how rare this was—and how lucky I was to find it over and over again.

Blanche Caffiere

Blanche Caffiere entered my life twice—first as my first-grade teacher, and later as my first “boss,” when I was in fourth grade at View Ridge Elementary and she was the librarian. At the time, I was a handful in (and out of) class: energetic, disruptive, constantly lost in my own thoughts. Most teachers and administrators saw me as a problem to be solved. But Mrs. Caffiere saw a problem-solver in me instead. When one of my teachers struggled with how to challenge me and channel my energy, she stepped in and gave me a job as her library assistant.

“What you need is kind of like a detective,” I said when she tasked me with finding missing books that were lost somewhere in the library. I warmed to the work immediately, roaming the stacks until I found each one. Then Mrs. Caffiere taught me the Dewey Decimal system by having me memorize a clever story about a caveman, so I could figure out where each book belonged. For a kid who loved reading and numbers, it was a dream job. I felt essential. I stayed through recess that first day, showed up early the next morning, and ended up working in the library for the rest of the year.

When my family moved and I had to leave View Ridge Elementary, I was most devastated about leaving my library job. “Who will find the lost books?” I asked. Mrs. Caffiere responded that I could be a library assistant at my new school. She understood that what I needed wasn’t just busy work, but a sense of being valued and trusted with real responsibility. She’d been teaching for nearly forty years when we met, which meant she’d seen every kind of student imaginable. But she had a particular gift for helping those at the extremes—the ones who were struggling or excelling—find their way. I was a little of both, and she certainly helped me find mine.

Paul Stocklin

Paul Stocklin’s eighth-grade math class at Lakeside changed my life in two profound ways, though I couldn’t have known it at the time. First, it was where I met Kent Evans, who would become my best friend and earliest “business” partner before his tragic death in a mountain climbing accident at age 17. Like me, Kent didn’t easily fit into the established cliques at Lakeside. Unlike me, he had a clear vision for his future, which inspired me to start thinking about my own.

It was also in Mr. Stocklin’s class that I first saw a teletype machine—an encounter that would shape my entire future. One morning, Mr. Stocklin led our class down a hall in McAllister House, a white clapboard building at Lakeside that was home to the school’s math department, where we heard an unusual “chug-chug-chug” sound echoing from inside a room. There, we saw something that looked like a typewriter with a rotary telephone dial. Mr. Stocklin explained that it was a teletype machine connected to a computer in California. With it, we could play games and even write our own computer programs—something I’d never thought I’d be able to do myself. That moment opened up a whole new world for me.

There’s a lot more I’ve come to appreciate about Mr. Stocklin, including how much he encouraged an early love of math in me. But it’s undeniable that he changed my life by facilitating two of the most important relationships of my early years: my friendship with Kent, and my introduction to computing. These were gifts from him that I’ll appreciate forever, even though one would end in heartbreak.

Bill Dougall

Bill Dougall embodied what made Lakeside special—he was a World War II Navy pilot and Boeing engineer who brought real-world experience to teaching. Beyond his degrees in engineering and education, he had even studied French literature at the Sorbonne. He was the kind of Renaissance man who took sabbaticals to build windmills in Kathmandu.

As head of Lakeside’s math department, Mr. Dougall was instrumental in bringing computer access to our school, something he and other faculty members pushed for after taking a summer computer class. Even though it was expensive—over $1,000 a year for the terminal and thousands more in computer time—he helped convince the Mothers’ Club to use the proceeds from their annual rummage sale to lease a Teletype ASR-33.

The fascinating thing about Mr. Dougall was that he didn’t actually know much about programming; he exhausted his knowledge within a week. But he had the vision to know it was important and the trust to let us students figure it out. His famous camping trips, a sacred tradition at Lakeside, showed another side of his belief in experiential learning. These treks took students through whatever weather the Pacific Northwest could throw at forty boys and a few intrepid teachers. They taught resilience, teamwork, and problem-solving in a way that no classroom ever could. That was the essence of Mr. Dougall’s teaching philosophy.

Fred Wright

Fred Wright was exactly the kind of teacher we needed in the computer room at Lakeside. He had no practical computer experience, though he’d studied the FORTRAN programming language. But he was relatively young (in his late twenties) and only recently hired, and he intuitively understood that the best way to get students to learn was to let us explore on our own terms. There was no sign-up sheet, no locked door, no formal instruction.

Instead, Mr. Wright let us figure things out ourselves and trusted that, without his guidance, we’d have to get creative. At some point, a student taped a sign above the door that said “Beware of the Wrath of Fred Wright”—a tongue-in-cheek nod to his laissez-faire oversight of the computer room. Some of the other teachers argued for tighter regulations, worried about what we might be doing in there unsupervised. But even though Mr. Wright occasionally popped in to break up a squabble or listen as someone explained their latest program, for the most part he defended our autonomy.