Listen to the Teachers

Infectious enthusiasm

Melinda on why she loves hearing from teachers.

What makes a great teacher great? It’s a good question at any time of year, but as teachers return to their classrooms in the weeks ahead, postering their walls and preparing their lesson plans, it’s a great time to focus on great teachers and great teaching, since there’s lots of evidence that it makes all the difference to student success. We’re focused on “back to school” in my own house, and it excites me to hear my kids talk about their year ahead—their classes, their classmates, and what teachers they’ll have for the coming year.

I enjoy talking to my kids’ teachers; in fact, I enjoy talking to teachers, period. It’s a lot of fun for me. I find their enthusiasm infectious. My role at the Gates Foundation allows me to talk to teachers from all over the country, and to seek their advice and insight on how to best achieve our goal of making sure all students in this country graduate from high school prepared for college or other forms of postsecondary education. By listening to what teachers have to say about what they see in their classrooms every single day, I learn how our foundation can support them in the most effective and efficient ways.

This summer, I spent time asking teachers for their feedback. The conversations were so enlightening that I wanted to share some of the themes that kept jumping out at me.

Great teachers are passionate.

My favorite moment in these conversations came when I asked these teachers why they’d gone into teaching. They all had an answer right away; their eyes lit up when they shared it, and their stories were powerful. A couple of teachers I spoke with went into teaching because their own teachers had inspired them and they wanted to pass that inspiration on. One woman said she started teaching just to pass time before starting law school, but once she’d started she loved it too much to stop. She never did manage to get to law school. Others talked about their subjects, and how their love of English, or chemistry, or history was something they just needed to ignite in others, or try. Whatever the source of their passion, passion was a common denominator, and a driver for great teachers.

Great teachers are true experts.

A lot of people believe that teaching math, for example, just involves knowing a little bit about math and then standing up in front of a bunch of kids and explaining it to them. In fact, teachers spend years honing both subject expertise and a unique set of teaching skills, figuring out how to structure their classrooms and their lessons to produce authentic learning rather than just the rote instruction. Holly Phillips, who teaches math in Kentucky, talked to me about what she called Monkey Syndrome: she can drill equations into her students’ brains, and they can mimic them to get good enough grades on tests, but they still don’t really know math. She’s spent a lot of time thinking about how to teach in new ways that let students see the underlying reasons for learning quadratic equations, cosines, and factoring. “They come up with so much more,” she said, “than I could think to put in a lesson.” Her story really struck me: great teachers are experts in not only WHAT they teach, but HOW to teach it in ways that will catch fire with their students.

Great teachers are committed to their students’ success.

There’s a common myth about teachers—that they know right away which students are going to succeed and which are going to fail, and they concentrate on the “good” students. But the teachers who talked to me blow that misconception out of the water. They spoke about their commitment to reaching all of their students, and many of them spent most of our time together talking about reaching the kids who didn’t get the material as easily. William Anderson, who teaches social science in Denver, put it this way: “There are very few teachers who wake up and say to themselves, I want this kid to be a failure. We wake up with success on our minds, and we work hard to instill that into kids.”

Great teachers want in on the conversation.

One last thing came through in my discussions with the teachers: they want to be part of the debate about school improvement in this country. “A lot of teachers feel like their voice isn’t heard,” said William, “and that regardless of what we say, people are just going to do things to us rather than with us.” Teachers may wake up with success for their students on their minds, but they can’t do it alone. They need support from parents, administrators, and legislators. One of the things we’re trying to do at our foundation is to help teachers get that support they’re looking for. Because if more of us entered into conversation with teachers and got w to hear them talk about what’s possible for our kids and our classrooms, we’d be a lot more optimistic about education. I know I am.

Come as you are

Wiggling is welcome in this kindergarten classroom

Kim Broomer’s classroom is one of the most unique and supportive learning environments I have ever heard of.

When I was a kid, I couldn’t sit still. My teachers used to get mad at me for squirming in my chair and chewing on my glasses and pencils. At the time, I felt like I was doing something wrong. Now I know that those movements helped me process my environment and stay engaged in class.

I probably would have felt a lot better about my restlessness if I had been in Kim Broomer’s class. Kim is this year’s Washington State Teacher of the Year, and her classroom is one of the most unique and supportive learning environments I have ever heard of.

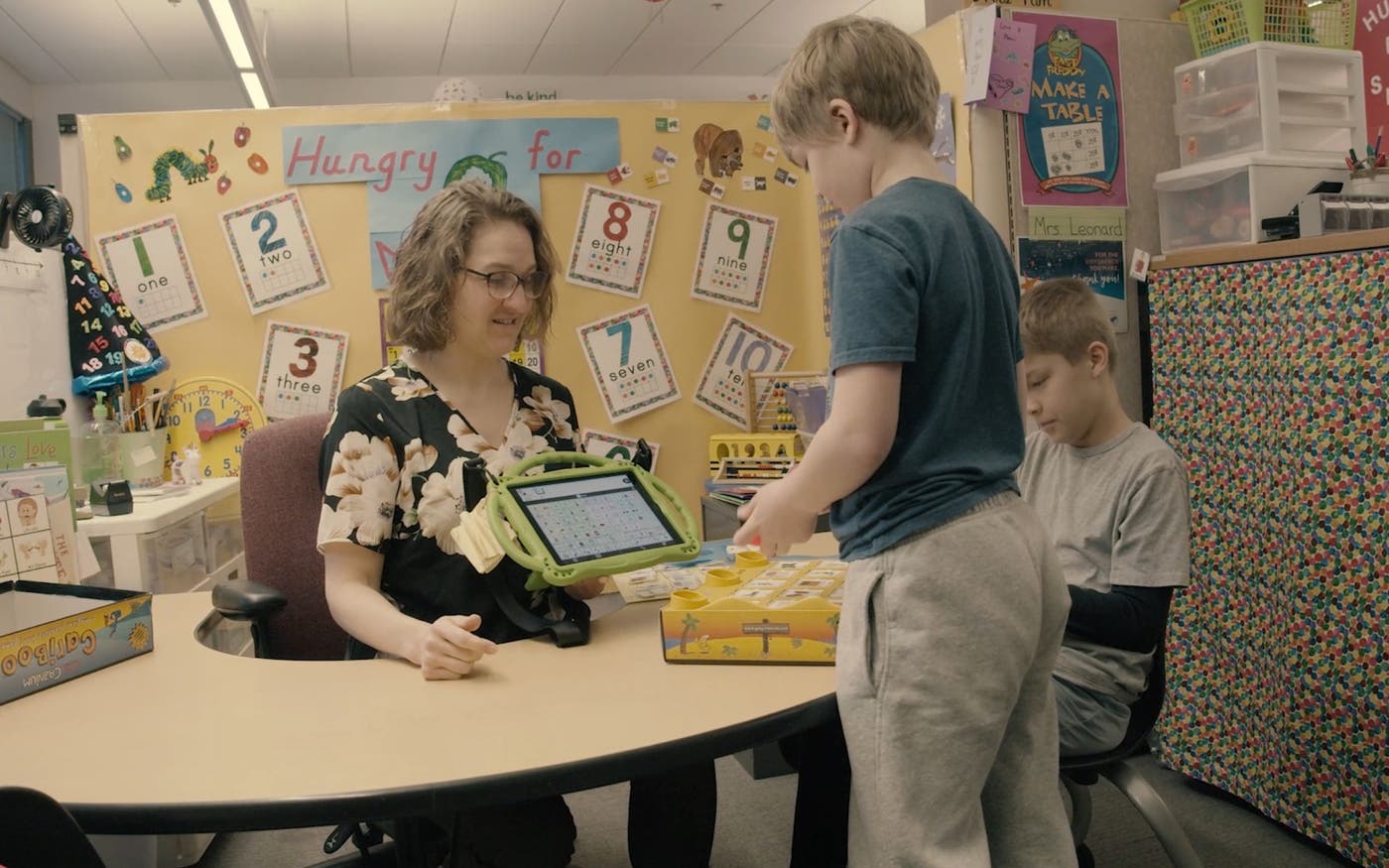

Kim teaches kindergarten at Ruby Bridges Elementary School in Woodinville, a suburb of Seattle located about 45 minutes from downtown. It’s a full-inclusion school, which means that students with a wide range of learning and communication needs learn alongside one another in the same class throughout the day.

Some of Kim’s students are non-speaking. Others are autistic, experience dyslexia, or have been identified as highly capable or multilingual learners. “At our school, we include all children,” she explains. “We don’t segregate students based on any one aspect of their identity.” Fittingly, the school is named after the civil rights icon who was the first Black student to integrate an all-white school in Louisiana.

Ruby Bridges Elementary opened five years ago in the middle of the pandemic. Kim helped launch the school, working with other staff and under the leadership of her principal, Cathi Davis—who was recently named the Washington State Elementary Principal of the Year. Together, the staff has built something truly exceptional.

Eighteen percent of the student body receive special education services, which is only a little higher than the national average of 15 percent. In other words, Kim’s classroom looks pretty much like any other in the U.S. at first glance. The differences only become obvious over the course of the day.

In most schools, students who need help from specialists leave their classroom to work with them. At Ruby Bridges, that’s not the case. Occupational therapists, language pathologists, and other professionals instead come into Kim’s classroom to work directly with kids. This means that kids get to remain in class, and all students get to benefit from the additional knowledge and support.

That makes a huge difference. When students are pulled out of class, they receive an average of 35 percent fewer instructional minutes. And being removed can send the wrong message—both to the student and to their peers—about who belongs and who doesn’t.

In contrast, Kim’s students learn that there’s nothing wrong with needing help—after all, everyone relies on some kind of support to live, learn, and work. Maybe you’re like me and you need glasses to see. Maybe you need to start your day with a cup of coffee, or you prefer to get work done while listening to music with headphones on. Maybe you’re like some of Kim’s students, and you use an app to help you communicate. “We all have strengths, and we all have things that we’re working on,” she says. “We all can succeed under the right atmosphere with the right supports.”

I was fascinated by Kim’s approach to sensory regulation in the classroom. Many of her students engage in stimming—self-regulating or repetitive movements that help them stay grounded and focused, like the kind I used to do as a kid (and still do today sometimes). These behaviors are often misunderstood or discouraged in traditional classrooms, but Kim sees them as valid and essential.

Special tools let Kim’s students regulate their sensory needs without disrupting the classroom. Some of her students like to wiggle or shake things, so she provides them with quiet toys that make no noise. She showed me special pen caps that are meant to be chewed on. She even has special wobble chairs that let students move their bodies while staying safe and engaged. Because these types of tools are available to everyone and so common in her class, her students don’t think twice about them. They’re simply seen as part of how people learn.

The benefits for students who have disabilities are obvious, but what about everyone else? Kim told me that some families worry that their kids might get less attention—but she makes a compelling case for why a full-inclusion classroom helps everyone. “All children benefit from learning in diverse communities,” Kim says. “In Kindergarten, where I teach, every student is still developing language, communication, and emotional regulation. It’s the perfect place to lay the foundation for inclusive learning.”

The data backs her up: Students at Ruby Bridges outperform district and state averages in reading and math. And, beyond academics, they’re learning empathy that will guide them through the rest of their lives. “Your child is going to be a kinder, more empathetic human being because they’ll have relationships with people who speak differently, move differently, and express themselves in different ways,” says Kim.

Unfortunately, as an elementary school, Ruby Bridges only serves kids through 5th grade. When students move on to middle school, they often find themselves separated from the inclusive community where they thrived. It’s heartbreaking for the families, and I wish they had the choice to continue. “One day, these kiddos will grow up,” Kim told me. “The relationships they build now in inclusive classrooms are the foundation for the communities they’ll lead tomorrow.”

I hope more schools follow Ruby Bridges’ example. It’s fantastic to see how Kim brings every child in and helps kids connect with one another. Her students aren’t just learning math and reading—they’re learning how to be the kind of people who build a better world.

Breaking New Ground

Can online classes change the game for some students?

The 2024 Washington State Teacher of the Year believes the answer is yes—and she’s innovating new techniques to support them.

When I was in high school, one of my favorite classes was drama. A teacher pushed me to sign up, and I was fully prepared to hate it—but I fell in love with acting. Drama pushed me to broaden myself, try something new, and see if I could succeed. I even gained enough confidence to audition for—and get—the lead in “Black Comedy,” the school play my senior year.

Blaire Penry, the 2024 Washington State Teacher of the Year, understands how transformative a class like drama can be, because she’s seen it happen with her own students. And I was blown away by how she uses technology to reimagine how students engage in the classroom.

Blaire teaches career and technical education, or CTE, and fine arts in the Auburn School District, which is located about 30 miles south of Seattle. Over the years, she has taught a wide range of electives—including marketing, worksite learning, career choices, and psychology, in addition to drama—to both middle and high school students.

What really sets Blaire apart, though, is her approach to online education. When schools switched to remote instruction in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Blaire quickly realized that the existing curriculum didn’t work. It just wasn’t engaging enough without the face-to-face interaction. At the time, her school district was doing fully synchronous instruction. Teachers did live instruction, students could ask questions, and classes operated on the same schedule as before. Still, her students struggled to connect with the material from their homes.

So, she helped develop a new curriculum that worked in an online setting and innovated new techniques to keep her students engaged.

Blaire created new materials and lesson plans that resonated more with Auburn students, 76 percent of whom are people of color—including a new social justice curriculum aimed at helping her kids become more active and informed citizens. Homeroom became a structured social period where students could get to know their teacher and each other, since the normal opportunities to connect—over lunch, or in the hallway between classes—aren’t available in online instruction. The chat function was used constantly throughout her classes, with Blaire checking in to make sure students were engaged and the kids asking (and answering!) questions about the material.

“It gave me this moment to dismantle my curriculum and build it back up with my community in mind, which is such a gift,” Blaire told me. “I found that creative challenge incredibly fulfilling, and it gave me a chance to, I think, become a better teacher.”

The work that Blaire and her colleagues did was eventually spun off into Auburn Online School. Although schools reopened in Washington in 2021 and many students returned in-person, a lot of students in her district continued to opt for remote instruction. Many of them lived in intergenerational households, with older family members who were at risk of becoming seriously ill from COVID-19. Auburn Online gave them a safe, high-quality option for continuing their education.

The Gates Foundation supported a lot of schools that offered this kind of support during the pandemic, so I wasn’t surprised to hear that some students continued to learn remotely to keep their loved ones safe. But what stunned me was how many kids wanted to stick with online instruction for reasons that had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Although many students struggled with the transition to online learning and lack of face-to-face interaction with their teachers and peers, Blaire found that a number of her kids not only adapted but thrived. Some needed extra flexibility so they could work a job or keep up with other responsibilities. Others benefited from having greater control of their learning environments. For example, they could focus much better in the comparative quiet of their own homes, or they had less anxiety when they could answer a question in a chat rather than by raising their hands in front of the whole class.

It blew my mind to learn that fully remote instruction works better for some students. Like many people, I’ve always thought of it as a necessary obstacle to overcome in times of necessity. But Blaire sees it as a tremendous opportunity for some families—and as a powerful tool for driving equity.

I was especially fascinated to hear how she teaches drama. I didn’t think it was a class that would lend itself well to online instruction, but Blaire convinced me otherwise.

“One of the things that is really fun about teaching drama online is that it gives students the space to explore and try things out in ways they might not with all eyes on them in a classroom,” she told me. For example, Blaire sets her students up in breakout rooms, where they can practice in small groups or with her. When it comes time to perform a monologue, they record it—and if they don’t like their performance, they just try it again until they have a version they’re comfortable with other people seeing.

“Some of my students might not have taken a drama class,” she says. “But when you release some of that immediate pressure of performing, you give them permission to be creative in ways they haven’t explored before.”

Blaire is clear that online education isn’t the right fit for everyone. But she’s a firm believer that families deserve it as an option.

Because she is such a big thinker about how technology can help students, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to ask her what she thinks about AI. Blaire is excited about how AI tools will help her better track her students’ progress and provide them with personalized tutors—two use cases I recently saw firsthand in Newark, NJ.

She hopes that teachers are given adequate training on using AI, especially given the biases it can reinforce. Blaire told me about a technology showcase she recently attended. The facilitator was showing off how AI can help teachers save time and asked it to put together a top ten list of recommended reading material for middle schoolers. Every author on the list was white, and almost all of them were men.

This is a solvable problem. AI can be programmed to be more representative and thoughtful in its answers—but it’s going to require input from brilliant teachers like Blaire, who understand the potential and limits of technology in the classroom.

“Online learning creates an opportunity for teachers to be a little bit fearless,” Blaire says. “It’s an opportunity to examine your students, examine your community, and then put it in the forefront of how you’re going to move forward. It’s exciting to try something new, be innovative, and disrupt the norm.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Signs of hope

Meet the teacher helping Deaf students navigate the world

Washington State Teacher of the Year Dana Miles uses bus schedules, coffee orders, and dinner recipes to teach her students about self-advocacy.

When I was a senior in high school, I spent part of the year living in Vancouver, Washington. I thought I got to know the town, which is just across the state border from Portland, pretty well while I was doing some programming for the local power company. But I recently found out Vancouver is home to one of the state’s most remarkable schools—and 17-year-old me had no idea.

The Washington School for the Deaf is the state’s only fully bilingual K-12 school in American Sign Language, or ASL, and English. Deaf and hard-of-hearing students come from across the state—many staying overnight during the week to attend classes—to learn in both languages. The school has had a lot to be proud of since its founding more than 135 years ago, but it recently added a new feather to its cap: WSD is home to Dana Miles, the 2023 Washington State Teacher of the Year.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Dana. I was blown away by her thoughtful, compassionate, and practical approach to teaching. As a graduate of WSD herself, she understands how her kids feel when they first step into her classroom. Many of them grew up in hearing families where they don’t sign, so they learned how to communicate later than most children. Some even join Dana’s classes with virtually no language at all.

“My students often feel insecure because maybe their English or ASL isn’t good enough,” she told me through an interpreter. “So I first want them to know that whatever they share during class is important. Once they realize what they say has importance, they feel like, ‘Okay, I matter.’ And that’s when they start learning.”

Dana teaches three classes to high school students that she describes broadly as “Adulting 101.” The first is a consumer math class, where students learn how to double recipes, calculate paycheck deductions, and more. The Gates Foundation supports many partners working to make math more engaging to students, and I think Dana’s focus on how math is used in the real world is super compelling.

Her favorite class to teach is Work Experience, because it’s all about helping her students imagine their future after school. As they work in a campus coffee shop, the school’s office, or off-campus at a local store, Dana helps them learn the hard and soft skills necessary for a successful career.

Many of Dana’s students will choose not to go to college, because there are other paths to a career that are more appealing to them. “A lot of my students really enjoy vocational fields because they’re hands-on,” she told me. “They don’t require as many linguistic requirements. Vocational fields can provide them with the potential to pursue a dream job.”

I was especially interested to hear about the third class Dana teaches, Applied Bilingual Language Arts. Just like in any bilingual class, her students study vocabulary and grammar in both languages at the same time. What makes Dana’s class unusual, though, is that all of the lessons they learn are directly connected to a real-world scenario they’re likely to encounter.

As an example, Dana told me about a transportation unit she does every year. If you’re a hearing person, chances are you learned a lot of what you know about transportation passively. You grew up overhearing your parents talk about what time a plane arrives or how the bus schedule just changed. If you’re deaf or hard-of-hearing, that might not have been the case. So, Dana teaches her students not only the vocabulary needed but how to read maps, navigate the city bus system, or even purchase car insurance. It’s a deeply practical approach to education that I believe every kid could benefit from.

I asked Dana if she could teach me a couple of signs, and she was kind enough to oblige me. I have a long way to go before I’m fluent, but I’m glad that I now know a couple key phrases. You can watch a video of Dana teaching me here:

I also asked Dana what hurdles she faces as a teacher. “For me, the challenge with bilingual education is the lack of resources,” she said. “We tend to create materials from scratch, because it’s not easy to find Bilingual Language Arts materials.” For example, if she’s teaching her students about job applications, she will film a video of her filling one out. She also records herself explaining what she’s doing in ASL, which she overlays on the corner of the screen. Videos are an effective tool, but they’re time consuming for Dana to create.

Fortunately, technology is improving a lot for the Deaf community. When Dana was in school, she had to ask a hearing family member to help her if she wanted to call someone. Now, her students have a huge array of communication tools at their disposal. She showed me two of them: an app called Cardzilla that transcribes spoken language super quickly and displays typed responses in a large font, and a video relay service, or VRS, on her phone that instantly connects her with an interpreter when she needs to call someone. (I was surprised, however, to learn no one has made an app that translates ASL to spoken English yet. I think it’s doable.)

Dana believes that introducing her students to all the tools available to them is one of her most important jobs. She says, "It is so critical for Deaf people to learn how to self-advocate, because often we are oppressed by so many barriers in our lives that we need to figure out how to overcome. Teachers have a responsibility to teach how to overcome those barriers.”

I am always amazed by the passion and commitment our Washington State Teachers of the Year bring to their work. Dana brings that dedication to an area of incredible need, and I left our meeting more inspired by our state’s remarkable teachers than ever. Educators like Dana make me proud to be a Washingtonian.

Native talents

“Just doing something like this is pretty revolutionary”

Why I made a deerskin medicine bag with Washington state’s Teacher of the Year.

Growing up in Seattle in the 1960s, I learned very little about the area’s indigenous people. Aside from camping trips my Boy Scout troop would take to a lodge in Chehalis, Washington, where it was at least acknowledged that a tribe had lived on the land, I heard a lot more about the arrival of the first white people in 1851 than about the people who had been here for centuries.

Today the Seattle area and Washington state do a better job of recognizing the role that Native people play in the community and helping them deal with the unique challenges they face. But there is a long way to go.

I recently got to learn more about these challenges and how things can get better when I met this year’s Washington State Teacher of the Year. His name is Jerad Koepp, and he runs the Native Student Program in the North Thurston Public Schools, located northeast of Olympia. Remarkably, he’s the first Native educator to receive the award.

Jerad, who is part of the Wukchumni tribe, doesn’t work in just one school. He sees around 200 Native students in 24 different schools across the district, which sits on traditional Nisqually land. In addition to teaching classes on Native history and culture, he travels around the district to meet with Native students. And he offers professional development for teachers and administrators to help them serve the students he works with. “We’re looking at what impacts our student engagement, student retention, and how Native people being represented makes a big difference,” he told me.

It was sobering to hear how badly the typical curriculum underrepresents Native people. “Over 80 percent of school textbooks don’t mention us after 1900,” Jerad told me. And that has a real impact on young people: “If you see yourself being made invisible or misrepresented to other students, that wears you down.” So sometimes his work is as basic as creating opportunities for Native students and their families to come together “and just be who we are for a little bit. Sometimes we talk about culture. Sometimes we just do homework, go over essays, or look at college applications.”

One of the first projects he does with his students is to show them how to make their own deerskin medicine bag, which is used to carry items of cultural importance like cedar, sage, and sweetgrass. The tradition of making them goes back thousands of years. Jerad helped me out as I tried making one myself:

While his students are sewing their bags, Jerad takes the opportunity to explore the deeper meaning behind them. “When we think about medicine,” he said, “we’re thinking conceptually about what we need for our social and emotional wellbeing, and how connecting to culture can help us get through tough times.”

Incredibly, for decades, many states including Washington banned medicine bags in their schools. Although Washington now allows them, Jerad told me that in some other states, items like sacred feathers and beadwork are still confiscated at high school graduation ceremonies. “Just doing something like this,” he said as we sewed up our deerskins, “is pretty revolutionary.”

I asked Jerad about the challenges that Native students face, and I appreciated the nuances in his answer. He acknowledged that traditional risk factors like poverty affect Native students disproportionately—but then he added, “It’s really easy to look at the data with a deficit mindset, rather than seeing all of our Native children as phenomenally asset-based. Because our students participate in incredible things: internships with their tribal governments, canoe journeys, and language programs. All of this comes with knowledge and history that isn’t measured within the Western education system.”

By helping students develop confidence in their identity, he aims to help them do better in school and in life after school, whether that means going to college or joining the workforce. He is also thinking about how to train the next generation of leaders in Native communities. For example, next year he will start teaching a Native Civics class for students who might want to get into tribal government.

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting many of Washington state’s Teachers of the Year, and every time, I think, “I wish we had more teachers like this person.” That is definitely the case with Jerad. I learned a lot from him. He’s a thoughtful leader, and I’m inspired by his commitment to helping Native students embrace their culture and make the most of their talents.

School of thought

My trip to the frontier of AI education

First Avenue Elementary School in Newark is pioneering the use of AI tools in the classroom.

When I was a kid, my parents took me to the World’s Fair in Seattle. It was amazing to see all these fantastic technologies that felt like something out of a science fiction novel. I asked them to take me back multiple times during the six months it was open here, and I remember walking away from the fairgrounds each time feeling that I had just caught a glimpse of the future.

That feeling came back to me recently as I walked out of a classroom in Newark, New Jersey.

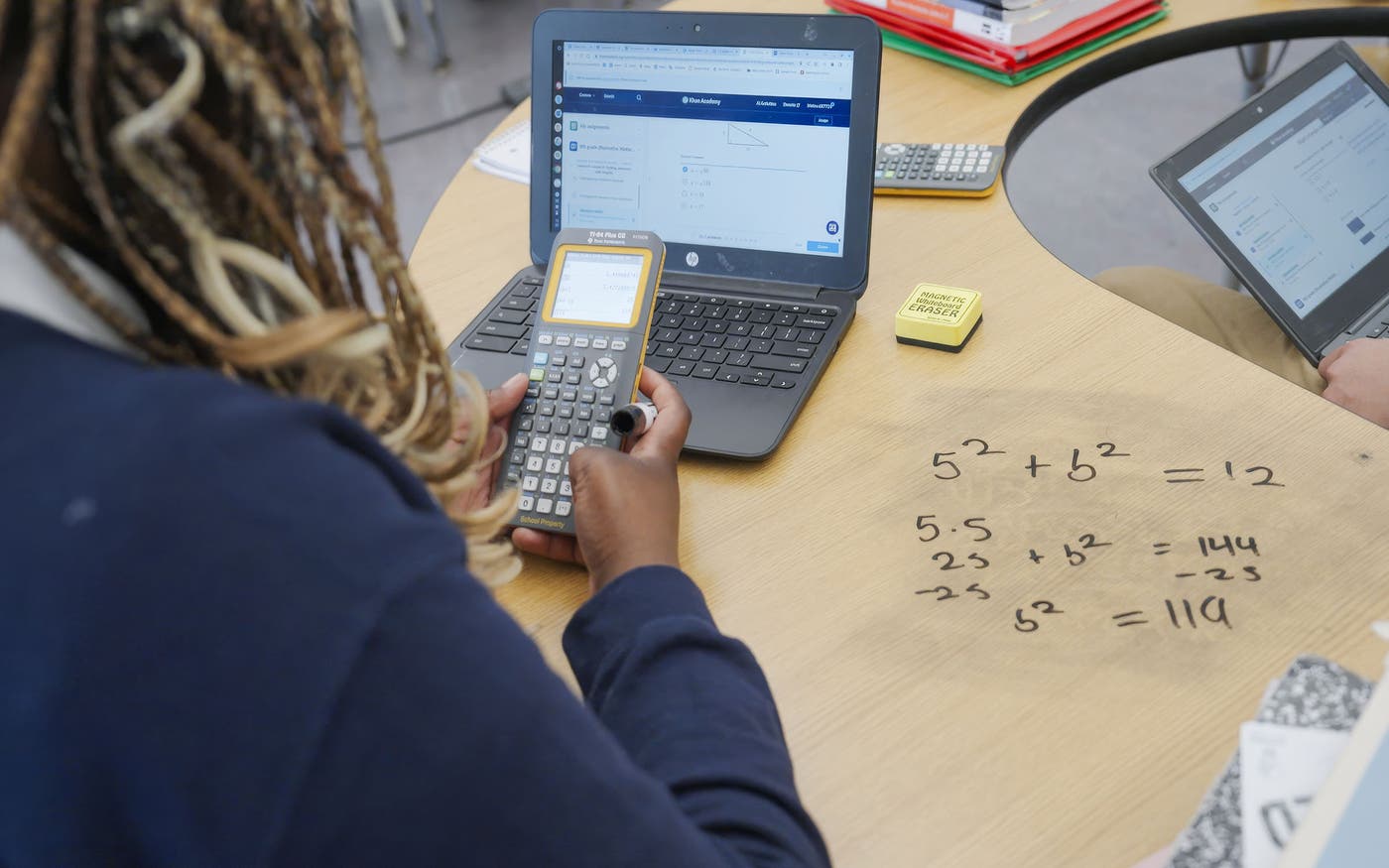

In May, I had the chance to visit the First Avenue Elementary School, where they’re pioneering the use of AI education in the classroom. The Newark School District is piloting Khanmigo, an AI-powered tutor and teacher support tool, and I couldn’t wait to see it for myself.

I’ve written a lot about Khanmigo on this blog. It was developed by Khan Academy, a terrific partner of the Gates Foundation. And I think Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy, is a visionary when it comes to harnessing the power of technology to help kids learn. (You can read my review of his new book, Brave New Words, here.)

We’re still in the early days of using AI in classrooms, but what I saw in Newark showed me the incredible potential of the technology.

I was blown away by how creatively the teachers were using the tools. Leticia Colon, an eighth-grade algebra teacher, explained how she used AI to create problem sets about hometown heroes the students might be interested in. In February, Khanmigo helped her develop equations that incorporated Newark boxer Shakur Stevenson’s workout routines, so her students could practice math skills while learning about a real-world role model.

Cheryl Drakeford, a third-grade math and science teacher, talked about how she uses Khanmigo to help create rubrics and lesson hooks for assignments. The technology gives her a first draft, which she then tailors for her students. For example, the AI once gave her a hook that used a generic story about a fruit stand, and she edited it to be about Pokémon cards and Roblox—two topics her students are passionate about. “Khanmigo gives me the blueprint, but I have to give the delivery,” she said.

Several of the teachers I met with showed me how they can access each student’s dashboard and get a summary of how they’re doing in a particular subject. They loved being able to easily and quickly track a student’s progress, because it’s saving them a lot of time. They were also excited about how their students are using Khanmigo as a personalized tutor.

This technology is far from perfect at this point. Although the students I met loved using Khanmigo overall, they also mentioned that it struggled to pronounce Hispanic names and complained that its only voice option is male—which makes it clear how much thought must still be put into making the technology inclusive and engaging for all students. In an ideal world, the AI would know what the students in Ms. Drakeford’s class are into, so she wouldn’t have to do any editing. And Ms. Colon told me it took her several tries to get Khanmigo to give her what she wanted.

In other words, my visit to Newark showed me where we are starting from with AI in the classroom, not where the technology will end up eventually. It reinforced my belief that AI will be a total game-changer for both teachers and students once the technology matures. Even today, when the teachers at First Avenue delegate routine tasks to AI assistants, they reclaim time for what matters most: connecting with students, sparking curiosity, and making sure every child feels seen and supported—especially those who need a little extra help.

Khanmigo is just one of many AI-powered education tools in the pipeline, and the Gates Foundation is focused on ensuring these tools reach and support all students, not just a few. Our goal is that they help level the playing field, not widen existing gaps. We’re currently working with educators across the country to get feedback and make the technology more responsive to their needs. Visits like the one I took to Newark are part of that process. It was fantastic to learn what teachers were enthused about and see how different students are engaging with AI.

The educators I met in Newark are true pioneers. Some were on the cutting edge, constantly looking for new ways to use AI in their classroom. Others were using it in a more limited fashion. I was impressed by how the school was able to support each teacher’s comfort level with the technology. They’re putting a lot of thought into change management and making sure that no educator is forced to try things that won’t work in their classroom.

That’s because, at the end of the day, teachers know best. If you hand them the right tools, they will always find a way to support their students. My visit to Newark left me more optimistic than ever that AI will help teachers do what they do best and free them up to focus on what matters most.

Ahead of the curve

Sal Khan is pioneering innovation in education…again

Brave New Words paints an inspiring picture of AI in the classroom.

When Chat GPT 4.0 launched last week, people across the internet (and the world) were blown away. Talking to AI has always felt a bit surreal—but OpenAI’s latest model feels like talking to a real person. You can actually speak to it, and have it talk back to you, without lags. It’s as lifelike as any AI we’ve seen so far, and the use cases are limitless. One of the first that came to my mind was how big a game-changer it will be in the classroom. Imagine every student having a personal tutor powered by this technology.

I recently read a terrific book on this topic called Brave New Words. It’s written by my friend (and podcast guest) Sal Khan, a longtime pioneer of innovation in education. Back in 2006, Sal founded Khan Academy to share the tutoring content he’d created for younger family members with a wider audience. Since then, his online educational platform has helped teach over 150 million people worldwide—including me and my kids.

Well before this recent AI boom, I considered him a visionary. When I learned he was writing this book, I couldn’t wait to read it. Like I expected, Brave New Words is a masterclass.

Chapter by chapter, Sal takes readers through his predictions—some have already come true since the book was written—for AI’s many applications in education. His main argument: AI will radically improve both student outcomes and teacher experiences, and help usher in a future where everyone has access to a world-class education.

You might be skeptical, especially if you—like me—have been following the EdTech movement for a while. For decades, exciting technologies and innovations have made headlines, accompanied by similarly bold promises to revolutionize learning and teaching as we know it—only to make a marginal impact in the classroom.

But drawing on his experience creating Khanmigo, an AI-powered tutor, Sal makes a compelling case that AI-powered technologies will be different. That’s because we finally have a way to give every student the kind of personalized learning, support, and guidance that’s historically been out of reach for most kids in most classrooms. As Sal puts it, “Getting every student a dedicated on-call human tutor is cost prohibitive.” AI tutors, on the other hand, aren’t.

Picture this: You're a seventh-grade student who struggles to keep up in math. But now, you have an AI tutor like the one Sal describes by your side. As you work through a challenging set of fraction problems, it won’t just give you the answer—it breaks each problem down into digestible steps. When you get stuck, it gives you easy-to-understand explanations and a gentle nudge in the right direction. When you finally get the answer, it generates targeted practice questions that help build your understanding and confidence.

And with the help of an AI tutor, the past comes to life in remarkable ways. While learning about Abraham Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War, you can have a “conversation” with the 16th president himself. (As Sal demonstrates in the book, conversations with one of my favorite literary figures, Jay Gatsby, are also an option.)

When the time comes to write your essay, don’t worry about the dreaded blank page. Instead, your AI tutor asks you thought-starters to help brainstorm. You get feedback on your outline in seconds, with tips to improve the logic or areas where you need more research. As you draft, the tutor evaluates your writing in real-time—almost impossible without this technology—and shows where you might clarify your ideas, provide more evidence, or address a counterargument. Before you submit, it gives detailed suggestions to refine your language and sharpen your points.

Is this cheating?

It’s a complicated question, and there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Sal notes that bouncing ideas off friends, asking family members to critique work, and using spellcheckers and tools like Grammarly—which can rephrase entire sentences—aren’t considered cheating today by most measures. Similarly, when used right, AI doesn’t work for students but with them to move something forward that they might otherwise get stuck on. That’s why, according to Sal, a lot of educators who first banned AI from class are now encouraging students to use it.

After all, mastery of AI won’t just be nice to have in a few years—for many professions, it’ll be necessary. Employees who can use AI effectively will be far more valuable than those who can’t. By incorporating this technology into education, we're both improving students’ experiences and outcomes and preparing them for the jobs of the future—which will become more enjoyable and fulfilling with AI in the mix.

That includes teaching. With every transformative innovation, there are fears of machines taking jobs. But when it comes to education, I agree with Sal: AI tools and tutors never can and never should replace teachers. What AI can do, though, is support and empower them.

Until now, most EdTech solutions, as great as they may be, haven’t meaningfully made teachers’ lives easier. But with AI, they can have a superhuman teaching assistant to handle routine tasks like lesson planning and grading—which take up almost half of a typical teacher's day. In seconds, an AI assistant can grade spelling tests or create a lesson plan connecting the Industrial Revolution to current events. It can even monitor each student's progress and give teachers instant feedback, allowing for a new era of personalized learning.

With AI assistants handling the mundane stuff, teachers can focus on what they do best: inspiring students, building relationships, and making sure everyone feels seen and supported—especially kids who need a little extra help.

Of course, there are challenges involved in bringing AI into schools at scale, and Sal is candid about them. We need systems that protect student privacy and mitigate biases. And there’s still a lot to do so that every kid has access to the devices and connectivity they need to use AI in the first place. No technology is a silver bullet for education. But I believe AI can be a game-changer and great equalizer in the classroom, the workforce, and beyond.

I recently visited First Avenue School in Newark, New Jersey, where Khanmigo is currently being piloted. We’re still in the early days, but it was amazing to see firsthand how AI can be used in the classroom—and to speak with students and teachers who are already reaping the benefits. It felt like catching a glimpse of the future. No one understands where education is headed better than Sal Khan, and I can't recommend Brave New Words enough.

Unconfuse Me with Bill Gates

Can AI help close the education gap? Sal Khan thinks so

In the second episode of my new podcast, I sat down with the founder of Khan Academy to talk about how artificial intelligence will transform education.

Sal Khan is a true pioneer of harnessing the power of technology to help kids learn. So, when I wanted to learn more about how artificial intelligence will transform education, I knew I had to talk to the founder of Khan Academy. I loved chatting with Sal about why tutoring is so important, how his new service Khanmigo is making the most of ChatGPT, and how we can keep teachers at the center of the classroom in the age of AI. We even found time to talk about our favorite teachers and the subject we wish we’d studied in school.

The future of agents

AI is about to completely change how you use computers

And upend the software industry.

I still love software as much today as I did when Paul Allen and I started Microsoft. But—even though it has improved a lot in the decades since then—in many ways, software is still pretty dumb.

To do any task on a computer, you have to tell your device which app to use. You can use Microsoft Word and Google Docs to draft a business proposal, but they can’t help you send an email, share a selfie, analyze data, schedule a party, or buy movie tickets. And even the best sites have an incomplete understanding of your work, personal life, interests, and relationships and a limited ability to use this information to do things for you. That’s the kind of thing that is only possible today with another human being, like a close friend or personal assistant.

In the next five years, this will change completely. You won’t have to use different apps for different tasks. You’ll simply tell your device, in everyday language, what you want to do. And depending on how much information you choose to share with it, the software will be able to respond personally because it will have a rich understanding of your life. In the near future, anyone who’s online will be able to have a personal assistant powered by artificial intelligence that’s far beyond today’s technology.

This type of software—something that responds to natural language and can accomplish many different tasks based on its knowledge of the user—is called an agent. I’ve been thinking about agents for nearly 30 years and wrote about them in my 1995 book The Road Ahead, but they’ve only recently become practical because of advances in AI.

Agents are not only going to change how everyone interacts with computers. They’re also going to upend the software industry, bringing about the biggest revolution in computing since we went from typing commands to tapping on icons.

A personal assistant for everyone

Some critics have pointed out that software companies have offered this kind of thing before, and users didn’t exactly embrace them. (People still joke about Clippy, the digital assistant that we included in Microsoft Office and later dropped.) Why will people use agents?

The answer is that they’ll be dramatically better. You’ll be able to have nuanced conversations with them. They will be much more personalized, and they won’t be limited to relatively simple tasks like writing a letter. Clippy has as much in common with agents as a rotary phone has with a mobile device.

An agent will be able to help you with all your activities if you want it to. With permission to follow your online interactions and real-world locations, it will develop a powerful understanding of the people, places, and activities you engage in. It will get your personal and work relationships, hobbies, preferences, and schedule. You’ll choose how and when it steps in to help with something or ask you to make a decision.

To see the dramatic change that agents will bring, let’s compare them to the AI tools available today. Most of these are bots. They’re limited to one app and generally only step in when you write a particular word or ask for help. Because they don’t remember how you use them from one time to the next, they don’t get better or learn any of your preferences. Clippy was a bot, not an agent.

Agents are smarter. They’re proactive—capable of making suggestions before you ask for them. They accomplish tasks across applications. They improve over time because they remember your activities and recognize intent and patterns in your behavior. Based on this information, they offer to provide what they think you need, although you will always make the final decisions.

Imagine that you want to plan a trip. A travel bot will identify hotels that fit your budget. An agent will know what time of year you’ll be traveling and, based on its knowledge about whether you always try a new destination or like to return to the same place repeatedly, it will be able to suggest locations. When asked, it will recommend things to do based on your interests and propensity for adventure, and it will book reservations at the types of restaurants you would enjoy. If you want this kind of deeply personalized planning today, you need to pay a travel agent and spend time telling them what you want.

The most exciting impact of AI agents is the way they will democratize services that today are too expensive for most people. They’ll have an especially big influence in four areas: health care, education, productivity, and entertainment and shopping.

Health care

Today, AI’s main role in healthcare is to help with administrative tasks. Abridge, Nuance DAX, and Nabla Copilot, for example, can capture audio during an appointment and then write up notes for the doctor to review.

The real shift will come when agents can help patients do basic triage, get advice about how to deal with health problems, and decide whether they need to seek treatment. These agents will also help healthcare workers make decisions and be more productive. (Already, apps like Glass Health can analyze a patient summary and suggest diagnoses for the doctor to consider.) Helping patients and healthcare workers will be especially beneficial for people in poor countries, where many never get to see a doctor at all.

These clinician-agents will be slower than others to roll out because getting things right is a matter of life and death. People will need to see evidence that health agents are beneficial overall, even though they won’t be perfect and will make mistakes. Of course, humans make mistakes too, and having no access to medical care is also a problem.

Mental health care is another example of a service that agents will make available to virtually everyone. Today, weekly therapy sessions seem like a luxury. But there is a lot of unmet need, and many people who could benefit from therapy don’t have access to it. For example, RAND found that half of all U.S. military veterans who need mental health care don’t get it.

AI agents that are well trained in mental health will make therapy much more affordable and easier to get. Wysa and Youper are two of the early chatbots here. But agents will go much deeper. If you choose to share enough information with a mental health agent, it will understand your life history and your relationships. It’ll be available when you need it, and it will never get impatient. It could even, with your permission, monitor your physical responses to therapy through your smart watch—like if your heart starts to race when you’re talking about a problem with your boss—and suggest when you should see a human therapist.

Education

For decades, I’ve been excited about all the ways that software would make teachers’ jobs easier and help students learn. It won’t replace teachers, but it will supplement their work—personalizing the work for students and liberating teachers from paperwork and other tasks so they can spend more time on the most important parts of the job. These changes are finally starting to happen in a dramatic way.

The current state of the art is Khanmigo, a text-based bot created by Khan Academy. It can tutor students in math, science, and the humanities—for example, it can explain the quadratic formula and create math problems to practice on. It can also help teachers do things like write lesson plans. I’ve been a fan and supporter of Sal Khan’s work for a long time and recently had him on my podcast to talk about education and AI.

But text-based bots are just the first wave—agents will open up many more learning opportunities.

For example, few families can pay for a tutor who works one-on-one with a student to supplement their classroom work. If agents can capture what makes a tutor effective, they’ll unlock this supplemental instruction for everyone who wants it. If a tutoring agent knows that a kid likes Minecraft and Taylor Swift, it will use Minecraft to teach them about calculating the volume and area of shapes, and Taylor’s lyrics to teach them about storytelling and rhyme schemes. The experience will be far richer—with graphics and sound, for example—and more personalized than today’s text-based tutors.

Productivity

There’s already a lot of competition in this field. Microsoft is making its Copilot part of Word, Excel, Outlook, and other services. Google is doing similar things with Assistant with Bard and its productivity tools. These copilots can do a lot—such as turn a written document into a slide deck, answer questions about a spreadsheet using natural language, and summarize email threads while representing each person’s point of view.

Agents will do even more. Having one will be like having a person dedicated to helping you with various tasks and doing them independently if you want. If you have an idea for a business, an agent will help you write up a business plan, create a presentation for it, and even generate images of what your product might look like. Companies will be able to make agents available for their employees to consult directly and be part of every meeting so they can answer questions.

Whether you work in an office or not, your agent will be able to help you in the same way that personal assistants support executives today. If your friend just had surgery, your agent will offer to send flowers and be able to order them for you. If you tell it you’d like to catch up with your old college roommate, it will work with their agent to find a time to get together, and just before you arrive, it will remind you that their oldest child just started college at the local university.

Entertainment and shopping

Already, AI can help you pick out a new TV and recommend movies, books, shows, and podcasts. Likewise, a company I’ve invested in, recently launched Pix, which lets you ask questions (“Which Robert Redford movies would I like and where can I watch them?”) and then makes recommendations based on what you’ve liked in the past. Spotify has an AI-powered DJ that not only plays songs based on your preferences but talks to you and can even call you by name.

Agents won’t simply make recommendations; they’ll help you act on them. If you want to buy a camera, you’ll have your agent read all the reviews for you, summarize them, make a recommendation, and place an order for it once you’ve made a decision. If you tell your agent that you want to watch Star Wars, it will know whether you’re subscribed to the right streaming service, and if you aren’t, it will offer to sign you up. And if you don’t know what you’re in the mood for, it will make customized suggestions and then figure out how to play the movie or show you choose.

You’ll also be able to get news and entertainment that’s been tailored to your interests. CurioAI, which creates a custom podcast on any subject you ask about, is a glimpse of what’s coming.

A shock wave in the tech industry

In short, agents will be able to help with virtually any activity and any area of life. The ramifications for the software business and for society will be profound.

In the computing industry, we talk about platforms—the technologies that apps and services are built on. Android, iOS, and Windows are all platforms. Agents will be the next platform.

To create a new app or service, you won’t need to know how to write code or do graphic design. You’ll just tell your agent what you want. It will be able to write the code, design the look and feel of the app, create a logo, and publish the app to an online store. OpenAI’s launch of GPTs this week offers a glimpse into the future where non-developers can easily create and share their own assistants.

Agents will affect how we use software as well as how it’s written. They’ll replace search sites because they’ll be better at finding information and summarizing it for you. They’ll replace many e-commerce sites because they’ll find the best price for you and won’t be restricted to just a few vendors. They’ll replace word processors, spreadsheets, and other productivity apps. Businesses that are separate today—search advertising, social networking with advertising, shopping, productivity software—will become one business.

I don’t think any single company will dominate the agents business--there will be many different AI engines available. Today, agents are embedded in other software like word processors and spreadsheets, but eventually they’ll operate on their own. Although some agents will be free to use (and supported by ads), I think you’ll pay for most of them, which means companies will have an incentive to make agents work on your behalf and not an advertiser’s. If the number of companies that have started working on AI just this year is any indication, there will be an exceptional amount of competition, which will make agents very inexpensive.

But before the sophisticated agents I’m describing become a reality, we need to confront a number of questions about the technology and how we’ll use it. I’ve written before about the issues that AI raises, so I’ll focus specifically on agents here.

The technical challenges

Nobody has figured out yet what the data structure for an agent will look like. To create personal agents, we need a new type of database that can capture all the nuances of your interests and relationships and quickly recall the information while maintaining your privacy. We are already seeing new ways of storing information, such as vector databases, that may be better for storing data generated by machine learning models.

Another open question is about how many agents people will interact with. Will your personal agent be separate from your therapist agent and your math tutor? If so, when will you want them to work with each other and when should they stay in their lanes?

How will you interact with your agent? Companies are exploring various options including apps, glasses, pendants, pins, and even holograms. All of these are possibilities, but I think the first big breakthrough in human-agent interaction will be earbuds. If your agent needs to check in with you, it will speak to you or show up on your phone. (“Your flight is delayed. Do you want to wait, or can I help rebook it?”) If you want, it will monitor sound coming into your ear and enhance it by blocking out background noise, amplifying speech that’s hard to hear, or making it easier to understand someone who’s speaking with a heavy accent.

There are other challenges too. There isn’t yet a standard protocol that will allow agents to talk to each other. The cost needs to come down so agents are affordable for everyone. It needs to be easier to prompt the agent in a way that will give you the right answer. We need to prevent hallucinations, especially in areas like health where accuracy is super-important, and make sure that agents don’t harm people as a result of their biases. And we don’t want agents to be able to do things they’re not supposed to. (Although I worry less about rogue agents than about human criminals using agents for malign purposes.)

Privacy and other big questions

As all of this comes together, the issues of online privacy and security will become even more urgent than they already are. You’ll want to be able to decide what information the agent has access to, so you’re confident that your data is shared with only people and companies you choose.

But who owns the data you share with your agent, and how do you ensure that it’s being used appropriately? No one wants to start getting ads related to something they told their therapist agent. Can law enforcement use your agent as evidence against you? When will your agent refuse to do something that could be harmful to you or someone else? Who picks the values that are built into agents?

There’s also the question of how much information your agent should share. Suppose you want to see a friend: If your agent talks to theirs, you don’t want it to say, "Oh, she’s seeing other friends on Tuesday and doesn’t want to include you.” And if your agent helps you write emails for work, it will need to know that it shouldn’t use personal information about you or proprietary data from a previous job.

Many of these questions are already top-of-mind for the tech industry and legislators. I recently participated in a forum on AI with other technology leaders that was organized by Sen. Chuck Schumer and attended by many U.S. senators. We shared ideas about these and other issues and talked about the need for lawmakers to adopt strong legislation.

But other issues won’t be decided by companies and governments. For example, agents could affect how we interact with friends and family. Today, you can show someone that you care about them by remembering details about their life—say, their birthday. But when they know your agent likely reminded you about it and took care of sending flowers, will it be as meaningful for them?

In the distant future, agents may even force humans to face profound questions about purpose. Imagine that agents become so good that everyone can have a high quality of life without working nearly as much. In a future like that, what would people do with their time? Would anyone still want to get an education when an agent has all the answers? Can you have a safe and thriving society when most people have a lot of free time on their hands?

But we’re a long way from that point. In the meantime, agents are coming. In the next few years, they will utterly change how we live our lives, online and off.

History helps

The risks of AI are real but manageable

The world has learned a lot about handling problems caused by breakthrough innovations.

The risks created by artificial intelligence can seem overwhelming. What happens to people who lose their jobs to an intelligent machine? Could AI affect the results of an election? What if a future AI decides it doesn’t need humans anymore and wants to get rid of us?

These are all fair questions, and the concerns they raise need to be taken seriously. But there’s a good reason to think that we can deal with them: This is not the first time a major innovation has introduced new threats that had to be controlled. We’ve done it before.

Whether it was the introduction of cars or the rise of personal computers and the Internet, people have managed through other transformative moments and, despite a lot of turbulence, come out better off in the end. Soon after the first automobiles were on the road, there was the first car crash. But we didn’t ban cars—we adopted speed limits, safety standards, licensing requirements, drunk-driving laws, and other rules of the road.

We’re now in the earliest stage of another profound change, the Age of AI. It’s analogous to those uncertain times before speed limits and seat belts. AI is changing so quickly that it isn’t clear exactly what will happen next. We’re facing big questions raised by the way the current technology works, the ways people will use it for ill intent, and the ways AI will change us as a society and as individuals.

In a moment like this, it’s natural to feel unsettled. But history shows that it’s possible to solve the challenges created by new technologies.

I have written before about how AI is going to revolutionize our lives. It will help solve problems—in health, education, climate change, and more—that used to seem intractable. The Gates Foundation is making it a priority, and our CEO, Mark Suzman, recently shared how he’s thinking about its role in reducing inequity.

I’ll have more to say in the future about the benefits of AI, but in this post, I want to acknowledge the concerns I hear and read most often, many of which I share, and explain how I think about them.

One thing that’s clear from everything that has been written so far about the risks of AI—and a lot has been written—is that no one has all the answers. Another thing that’s clear to me is that the future of AI is not as grim as some people think or as rosy as others think. The risks are real, but I am optimistic that they can be managed. As I go through each concern, I’ll return to a few themes:

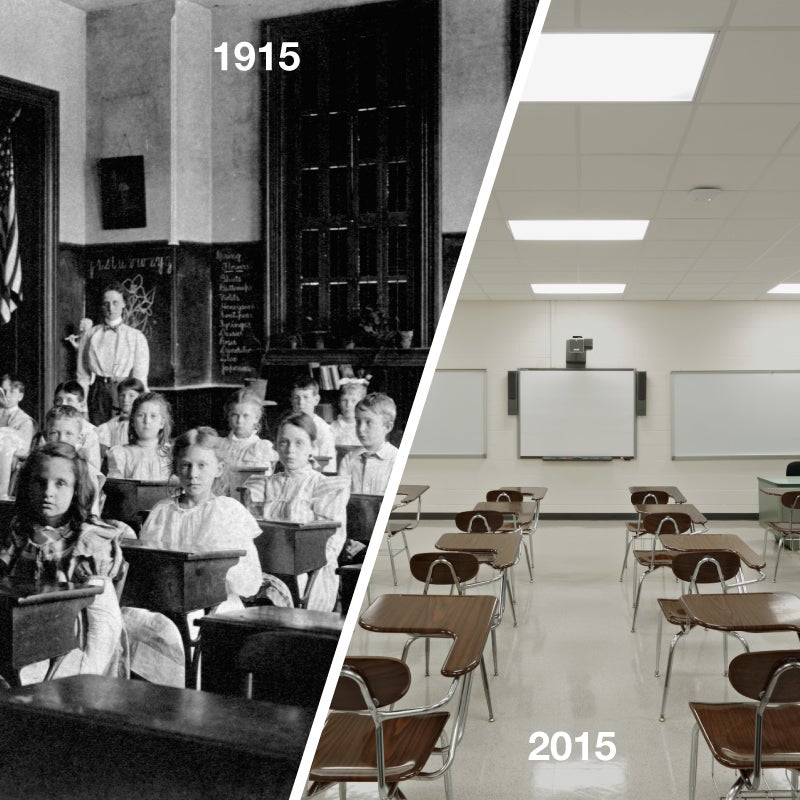

- Many of the problems caused by AI have a historical precedent. For example, it will have a big impact on education, but so did handheld calculators a few decades ago and, more recently, allowing computers in the classroom. We can learn from what’s worked in the past.

- Many of the problems caused by AI can also be managed with the help of AI.

- We’ll need to adapt old laws and adopt new ones—just as existing laws against fraud had to be tailored to the online world.

In this post, I’m going to focus on the risks that are already present, or soon will be. I’m not dealing with what happens when we develop an AI that can learn any subject or task, as opposed to today’s purpose-built AIs. Whether we reach that point in a decade or a century, society will need to reckon with profound questions. What if a super AI establishes its own goals? What if they conflict with humanity’s? Should we even make a super AI at all?

But thinking about these longer-term risks should not come at the expense of the more immediate ones. I’ll turn to them now.

Deepfakes and misinformation generated by AI could undermine elections and democracy.

The idea that technology can be used to spread lies and untruths is not new. People have been doing it with books and leaflets for centuries. It became much easier with the advent of word processors, laser printers, email, and social networks.

AI takes this problem of fake text and extends it, allowing virtually anyone to create fake audio and video, known as deepfakes. If you get a voice message that sounds like your child saying “I’ve been kidnapped, please send $1,000 to this bank account within the next 10 minutes, and don’t call the police,” it’s going to have a horrific emotional impact far beyond the effect of an email that says the same thing.

On a bigger scale, AI-generated deepfakes could be used to try to tilt an election. Of course, it doesn’t take sophisticated technology to sow doubt about the legitimate winner of an election, but AI will make it easier.

There are already phony videos that feature fabricated footage of well-known politicians. Imagine that on the morning of a major election, a video showing one of the candidates robbing a bank goes viral. It’s fake, but it takes news outlets and the campaign several hours to prove it. How many people will see it and change their votes at the last minute? It could tip the scales, especially in a close election.

When OpenAI co-founder Sam Altman testified before a U.S. Senate committee recently, Senators from both parties zeroed in on AI’s impact on elections and democracy. I hope this subject continues to move up everyone’s agenda.

We certainly have not solved the problem of misinformation and deepfakes. But two things make me guardedly optimistic. One is that people are capable of learning not to take everything at face value. For years, email users fell for scams where someone posing as a Nigeran prince promised a big payoff in return for sharing your credit card number. But eventually, most people learned to look twice at those emails. As the scams got more sophisticated, so did many of their targets. We’ll need to build the same muscle for deepfakes.

The other thing that makes me hopeful is that AI can help identify deepfakes as well as create them. Intel, for example, has developed a deepfake detector, and the government agency DARPA is working on technology to identify whether video or audio has been manipulated.

This will be a cyclical process: Someone finds a way to detect fakery, someone else figures out how to counter it, someone else develops counter-countermeasures, and so on. It won’t be a perfect success, but we won’t be helpless either.

AI makes it easier to launch attacks on people and governments.

Today, when hackers want to find exploitable flaws in software, they do it by brute force—writing code that bangs away at potential weaknesses until they discover a way in. It involves going down a lot of blind alleys, which means it takes time and patience.

Security experts who want to counter hackers have to do the same thing. Every software patch you install on your phone or laptop represents many hours of searching, by people with good and bad intentions alike.

AI models will accelerate this process by helping hackers write more effective code. They’ll also be able to use public information about individuals, like where they work and who their friends are, to develop phishing attacks that are more advanced than the ones we see today.

The good news is that AI can be used for good purposes as well as bad ones. Government and private-sector security teams need to have the latest tools for finding and fixing security flaws before criminals can take advantage of them. I hope the software security industry will expand the work they’re already doing on this front—it ought to be a top concern for them.

This is also why we should not try to temporarily keep people from implementing new developments in AI, as some have proposed. Cyber-criminals won’t stop making new tools. Nor will people who want to use AI to design nuclear weapons and bioterror attacks. The effort to stop them needs to continue at the same pace.

There’s a related risk at the global level: an arms race for AI that can be used to design and launch cyberattacks against other countries. Every government wants to have the most powerful technology so it can deter attacks from its adversaries. This incentive to not let anyone get ahead could spark a race to create increasingly dangerous cyber weapons. Everyone would be worse off.

That’s a scary thought, but we have history to guide us. Although the world’s nuclear nonproliferation regime has its faults, it has prevented the all-out nuclear war that my generation was so afraid of when we were growing up. Governments should consider creating a global body for AI similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

AI will take away people’s jobs.

In the next few years, the main impact of AI on work will be to help people do their jobs more efficiently. That will be true whether they work in a factory or in an office handling sales calls and accounts payable. Eventually, AI will be good enough at expressing ideas that it will be able to write your emails and manage your inbox for you. You’ll be able to write a request in plain English, or any other language, and generate a rich presentation on your work.

As I argued in my February post, it’s good for society when productivity goes up. It gives people more time to do other things, at work and at home. And the demand for people who help others—teaching, caring for patients, and supporting the elderly, for example—will never go away. But it is true that some workers will need support and retraining as we make this transition into an AI-powered workplace. That’s a role for governments and businesses, and they’ll need to manage it well so that workers aren’t left behind—to avoid the kind of disruption in people’s lives that has happened during the decline of manufacturing jobs in the United States.

Also, keep in mind that this is not the first time a new technology has caused a big shift in the labor market. I don’t think AI’s impact will be as dramatic as the Industrial Revolution, but it certainly will be as big as the introduction of the PC. Word processing applications didn’t do away with office work, but they changed it forever. Employers and employees had to adapt, and they did. The shift caused by AI will be a bumpy transition, but there is every reason to think we can reduce the disruption to people’s lives and livelihoods.

AI inherits our biases and makes things up.

Hallucinations—the term for when an AI confidently makes some claim that simply is not true—usually happen because the machine doesn’t understand the context for your request. Ask an AI to write a short story about taking a vacation to the moon and it might give you a very imaginative answer. But ask it to help you plan a trip to Tanzania, and it might try to send you to a hotel that doesn’t exist.

Another risk with artificial intelligence is that it reflects or even worsens existing biases against people of certain gender identities, races, ethnicities, and so on.

To understand why hallucinations and biases happen, it’s important to know how the most common AI models work today. They are essentially very sophisticated versions of the code that allows your email app to predict the next word you’re going to type: They scan enormous amounts of text—just about everything available online, in some cases—and analyze it to find patterns in human language.

When you pose a question to an AI, it looks at the words you used and then searches for chunks of text that are often associated with those words. If you write “list the ingredients for pancakes,” it might notice that the words “flour, sugar, salt, baking powder, milk, and eggs” often appear with that phrase. Then, based on what it knows about the order in which those words usually appear, it generates an answer. (AI models that work this way are using what's called a transformer. GPT-4 is one such model.)

This process explains why an AI might experience hallucinations or appear to be biased. It has no context for the questions you ask or the things you tell it. If you tell one that it made a mistake, it might say, “Sorry, I mistyped that.” But that’s a hallucination—it didn’t type anything. It only says that because it has scanned enough text to know that “Sorry, I mistyped that” is a sentence people often write after someone corrects them.

Similarly, AI models inherit whatever prejudices are baked into the text they’re trained on. If one reads a lot about, say, physicians, and the text mostly mentions male doctors, then its answers will assume that most doctors are men.

Although some researchers think hallucinations are an inherent problem, I don’t agree. I’m optimistic that, over time, AI models can be taught to distinguish fact from fiction. OpenAI, for example, is doing promising work on this front.

Other organizations, including the Alan Turing Institute and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, are working on the bias problem. One approach is to build human values and higher-level reasoning into AI. It’s analogous to the way a self-aware human works: Maybe you assume that most doctors are men, but you’re conscious enough of this assumption to know that you have to intentionally fight it. AI can operate in a similar way, especially if the models are designed by people from diverse backgrounds.

Finally, everyone who uses AI needs to be aware of the bias problem and become an informed user. The essay you ask an AI to draft could be as riddled with prejudices as it is with factual errors. You’ll need to check your AI’s biases as well as your own.

Students won’t learn to write because AI will do the work for them.

Many teachers are worried about the ways in which AI will undermine their work with students. In a time when anyone with Internet access can use AI to write a respectable first draft of an essay, what’s to keep students from turning it in as their own work?

There are already AI tools that are learning to tell whether something was written by a person or by a computer, so teachers can tell when their students aren’t doing their own work. But some teachers aren’t trying to stop their students from using AI in their writing—they’re actually encouraging it.

In January, a veteran English teacher named Cherie Shields wrote an article in Education Week about how she uses ChatGPT in her classroom. It has helped her students with everything from getting started on an essay to writing outlines and even giving them feedback on their work.

“Teachers will have to embrace AI technology as another tool students have access to,” she wrote. “Just like we once taught students how to do a proper Google search, teachers should design clear lessons around how the ChatGPT bot can assist with essay writing. Acknowledging AI’s existence and helping students work with it could revolutionize how we teach.” Not every teacher has the time to learn and use a new tool, but educators like Cherie Shields make a good argument that those who do will benefit a lot.

It reminds me of the time when electronic calculators became widespread in the 1970s and 1980s. Some math teachers worried that students would stop learning how to do basic arithmetic, but others embraced the new technology and focused on the thinking skills behind the arithmetic.

There’s another way that AI can help with writing and critical thinking. Especially in these early days, when hallucinations and biases are still a problem, educators can have AI generate articles and then work with their students to check the facts. Education nonprofits like Khan Academy and OER Project, which I fund, offer teachers and students free online tools that put a big emphasis on testing assertions. Few skills are more important than knowing how to distinguish what’s true from what’s false.

We do need to make sure that education software helps close the achievement gap, rather than making it worse. Today’s software is mostly geared toward empowering students who are already motivated. It can develop a study plan for you, point you toward good resources, and test your knowledge. But it doesn’t yet know how to draw you into a subject you’re not already interested in. That’s a problem that developers will need to solve so that students of all types can benefit from AI.

What’s next?

I believe there are more reasons than not to be optimistic that we can manage the risks of AI while maximizing their benefits. But we need to move fast.

Governments need to build up expertise in artificial intelligence so they can make informed laws and regulations that respond to this new technology. They’ll need to grapple with misinformation and deepfakes, security threats, changes to the job market, and the impact on education. To cite just one example: The law needs to be clear about which uses of deepfakes are legal and about how deepfakes should be labeled so everyone understands when something they’re seeing or hearing is not genuine

Political leaders will need to be equipped to have informed, thoughtful dialogue with their constituents. They’ll also need to decide how much to collaborate with other countries on these issues versus going it alone.

In the private sector, AI companies need to pursue their work safely and responsibly. That includes protecting people’s privacy, making sure their AI models reflect basic human values, minimizing bias, spreading the benefits to as many people as possible, and preventing the technology from being used by criminals or terrorists. Companies in many sectors of the economy will need to help their employees make the transition to an AI-centric workplace so that no one gets left behind. And customers should always know when they’re interacting with an AI and not a human.

Finally, I encourage everyone to follow developments in AI as much as possible. It’s the most transformative innovation any of us will see in our lifetimes, and a healthy public debate will depend on everyone being knowledgeable about the technology, its benefits, and its risks. The benefits will be massive, and the best reason to believe that we can manage the risks is that we have done it before.

Sum-thing new

What does popcorn have to do with math?

It’s part of a new approach to teaching America’s least favorite subject.

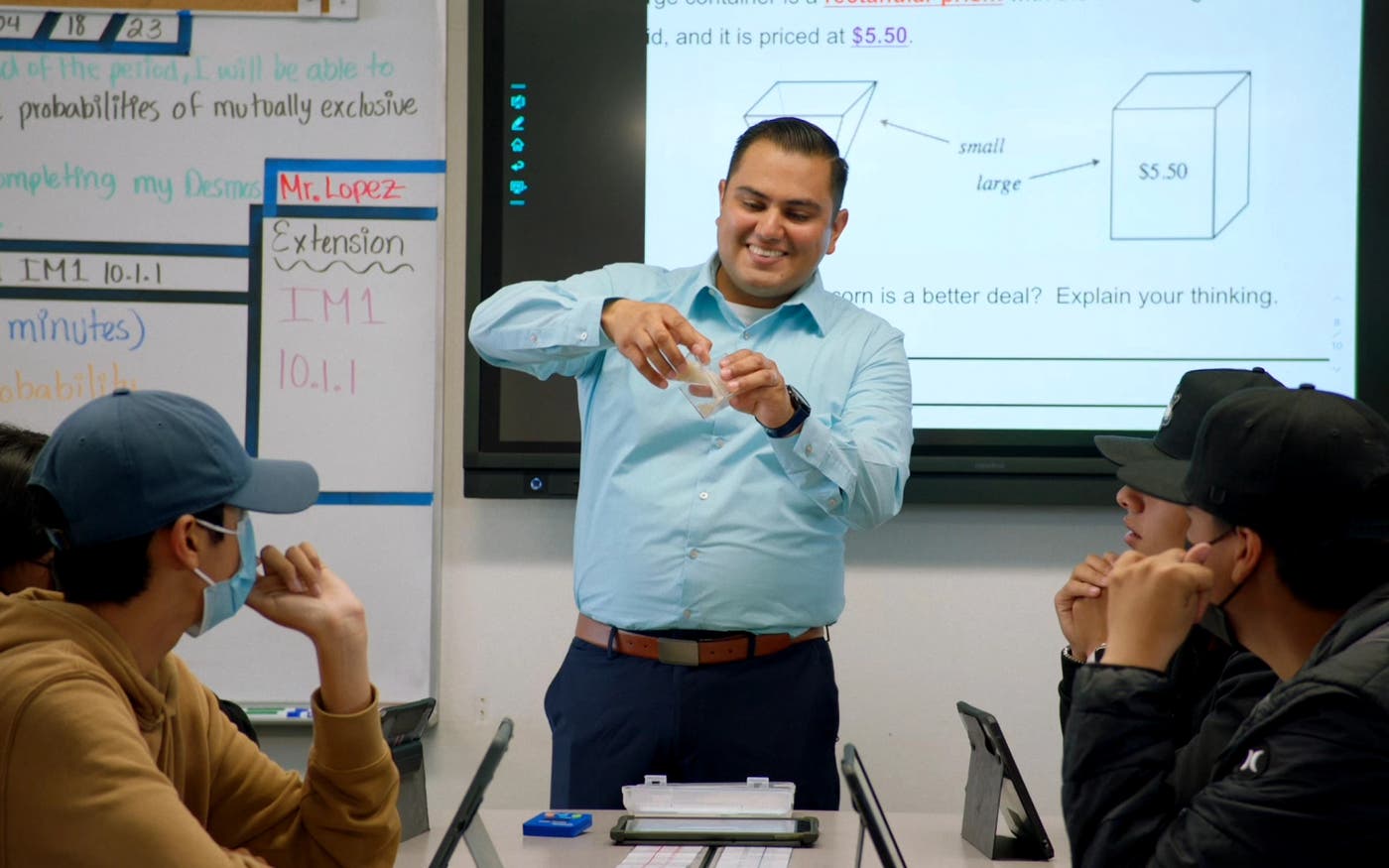

Do you know how to calculate the volume of a prism? What about a pyramid? And what does either have to do with movie theater popcorn?

Back in April, I spent the day at Chula Vista Middle School in Southern California learning what these questions have to do with graduating from college. I was there to meet with school and district leaders and join an eighth-grade math class taught by a remarkable teacher named Amilcar Fernandez, who also runs the math department and develops its curriculum. Over the past few years, Mr. Fernandez has been trying to transform how Chula Vista teaches what is widely cited as American students’ “least favorite subject”—and has been since at least the year I was born.

While my love of math is no secret, I know many people don’t feel similarly. To them, the subject often feels abstract, even irrelevant. And with the rise of calculators, then computers, and now AI chatbots, it’s getting harder and harder to explain to students why they should learn how to do long division or find the area of a trapezoid by hand.

The truth is that math is more than just a bunch of numbers—much more. Not only are math skills relevant to our everyday lives in ways we might not realize, they’re also a powerful indicator of how successful those lives will be. As I’ve written in the past, research shows that students who pass Algebra 1 by ninth grade are more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree (in any major) and go on to a well-paid career. If they fail the course, they only have a one-in-five chance of graduating from high school.

So it’s critical that students build the foundation in math they need to take on that tough course, which is the most frequently failed high school course in the country. But so many don’t. Earlier this year, the National Assessment Governing Board released its Long-Term Trend Report, which showed that math scores for 13-year-old students in seventh and eighth grade fell nine points compared to 2020 and 14 points compared to a decade ago—dropping to levels not seen since the 1990s.