High-Stakes Steaks

Is there enough meat for everyone?

Can we produce enough meat for everyone without wrecking the planet?

In my late twenties I went vegetarian for a year. Some of my friends were strict non-meat-eaters, and I wanted to try it out. Plus I was flying a lot for work and found that the airplane meals made with tomatoes and beans just tasted better than the shoe-leather beef. In the end, though, I couldn’t keep it going, and I eventually returned to my carnivorous ways.

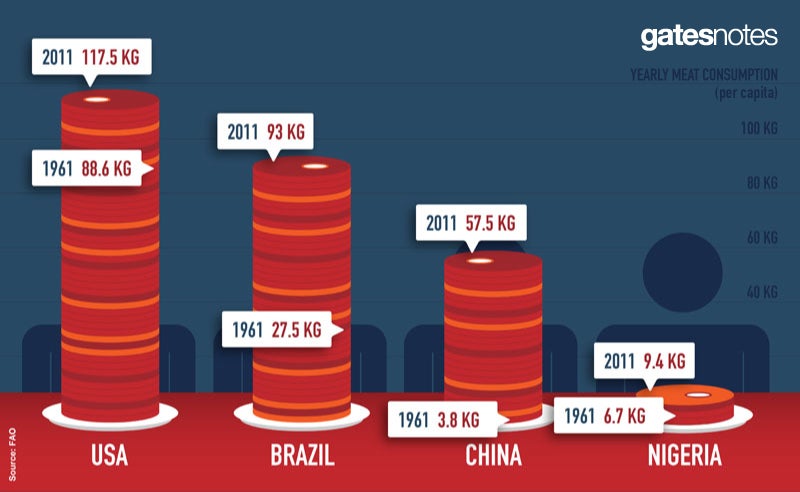

Years later, I came to realize that it was a luxury for me to spurn meat. In most places, as people earn more money, they want to eat more meat. Brazil’s per-capita consumption has gone up fourfold since 1950. China’s nearly doubled in the 1990s. Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Japan have also seen big increases.

More countries are sure to follow, and that’s a good thing. Meat is a great source of high-quality proteins that help children fully develop mentally and physically. In fact part of our foundation’s health strategy involves getting more meat, dairy, and eggs into the diets of children in Africa.

But there’s also a problem. Raising animals can take a big toll on the environment. You have to feed the animal far more calories than you extract when you eat it. It’s especially problematic as we convert large swaths of land from crops that feed people to crops that feed cows and pigs. Plus clearing forests to make more farmland contributes to climate change, as do the greenhouse gases produced by all those animals.

The richer the world gets, the more meat it eats; the more meat it eats, the bigger the threat to the planet. How do we square this circle?

I can’t think of anyone better equipped to present a clear-eyed analysis of this subject than Vaclav Smil. I have written several times before about how much I admire Smil’s work. When he tackles a subject, he doesn’t look at just one piece of it. He examines every angle. Even if I don’t agree with all of his conclusions, I always learn a lot from reading him.

That is certainly true of his book Should We Eat Meat?. He starts by trying to define meat (it’s surprisingly slippery—do you count kangaroos? crickets?), then explores its role in human evolution, various countries’ annual consumption (the United States leads the way with roughly 117 kilograms of carcass weight per person), and the health and environmental risks. He also touches on ethical questions about raising animals for slaughter and covers some simple ways to eliminate the needless cruelty involved.

As usual, Smil offers up some intriguing statistics along the way. A quarter of all ice-free land in the world is used for grazing livestock. Every year, the average meat-eating American ingests more than enough blood to fill a soda can. And Americans eat a lot of pepperoni:

Another thing Smil loves to do is question the conventional wisdom. For example, you may have read that raising meat for food requires a lot of water. This has been in the news lately because of the drought in California. Estimates vary, but the consensus is that between watering the animals, cleaning up after them, and growing crops to feed them (far and away the biggest use), it takes several thousand liters of water to produce one kilogram of boneless beef.

But Smil shows you how the picture is more complicated. It turns out that not all water is created equal. Nearly 90 percent of the water needed for livestock production is what’s called green water, used to grow grass and such. In most places, all but a tiny fraction of green water comes from rain, and because most green water eventually evaporates back into the atmosphere, it’s not really consumed.

As Smil writes, “the same water molecules that were a part of producing Midwestern corn to feed pigs in Iowa may help to grow, just a few hours later, soybeans in Illinois… or, a week later, grass grazed by beef cattle in Wales.” One study that excluded green water found that it takes just 44 liters—not thousands—to produce a kilo of beef. This is the kind of thing Smil excels at: using facts and analysis to examine widely held beliefs.

Returning to the question at hand—how can we make enough meat without destroying the planet?—one solution would be to ask the biggest carnivores (Americans and others) to cut back, by as much as half. Although it might be possible to get people in richer countries to eat less or shift toward less-intensive meats like chicken, I don’t think it’s realistic to expect large numbers of people to make drastic reductions. Evolution turned us into omnivores.

But there are reasons to be optimistic. For one thing, the world’s appetite for meat may eventually level off. Consumption has plateaued and even declined a bit in many rich countries, including France, Germany, and the United States. I also believe that innovation will improve our ability to produce meat. Cheaper energy and better crop varieties will drive up agricultural productivity, especially in Africa, so we won’t have to choose as often between feeding animals and feeding people.

I’m also hopeful about the future of meat substitutes. I have invested in some companies working on this and am impressed with the results so far. Smil is skeptical that it will have a big impact—and it is true that today the best products are sold mostly in fancy grocery stores—but I think it has potential.

With a little moderation and more innovation, I do believe the world can meet its need for meat.