Hands off the wheel

The rules of the road are about to change

I believe we’ll reach a tipping point with autonomous vehicles within the next decade.

I’ve always been a car guy. When I was younger, I used to love driving fast (sometimes too fast). Now, I look forward to my daily commute to work. There’s something so fun yet meditative about driving a car.

Despite that, I’m excited for the day I get to hand over control of my car to a machine.

That day is coming sooner rather than later. We’ve made tremendous progress on autonomous vehicles, or AVs, in recent years, and I believe we’ll reach a tipping point within the next decade. When it happens, AVs will change transportation as dramatically as the PC changed office work. A lot of this development has been enabled by the progress made in artificial intelligence more broadly. (I recently shared my thoughts about AI on this blog. You can read them here.)

Some background for those who might not know a lot about AVs: The best way to understand where we are today is by looking at the Society of American Engineers, or SAE, classification system. This is widely used to describe how autonomous a vehicle is.

In levels 0-2, a human driver is in full control of the car, but the vehicle can provide assistance through features like adaptive cruise control and lane centering. Level 3 is when the technology starts to move from the driver being in control to the vehicle being in control. By the time you reach the highest level, the car can be fully autonomous at all times and under all conditions—the level 5 vehicles of the future might not have steering wheels at all.

Right now, we’re close to the tipping point—between levels 2 and 3—when cars are becoming available that allow the driver to take their hands off the wheel and let the system drive in certain circumstances. The first level 3 car was recently approved for use in the United States, although only in very specific conditions: Autonomous mode is permitted if you’re going under 40 mph on a highway in Nevada on a sunny day.

Over the next decade, we’ll start to see more vehicles crossing this threshold. AVs are rapidly reaching the point where almost all of the technology required has been invented. Now, the focus is on refining algorithms and perfecting the engineering. There have been huge advances in recent years—especially in sensors, which scan the surrounding environment and tell the vehicle about things it needs to react to, like pedestrians crossing the street or another driver who swerves into your lane.

There are a lot of different approaches to AVs in development. Many vehicle manufacturers—like GM, Honda, and Tesla—are working on models that look like regular cars but have autonomous features. Then there are companies entirely focused on AVs, some of whose products are pushing the boundaries of what a vehicle can be—like a perfectly symmetrical robotaxi or public transit pods. Many others are developing components that can be installed to give an existing vehicle autonomous capabilities.

I recently had the opportunity to test drive—or test ride, I guess—a vehicle made by the British company Wayve, which has a fairly novel approach. While a lot of AVs can only navigate on streets that have been loaded into their system, the Wayve vehicle operates more like a person. It can drive anywhere a human can drive.

When you get behind the wheel of a car, you rely on the knowledge you’ve accumulated from every other drive you’ve ever taken. That’s why you know what to do at a stop sign, even if you’ve never seen that particular sign on that specific road before. Wayve uses deep learning techniques to do the same thing. The algorithm learns by example. It applies lessons acquired from lots of real world driving and simulations to interpret its surroundings and respond in real time.

The result was a memorable ride. The car drove us around downtown London, which is one of the most challenging driving environments imaginable, and it was a bit surreal to be in the car as it dodged all the traffic. (Since the car is still in development, we had a safety driver in the car just in case, and she assumed control several times.)

It’s not clear yet which approaches will be the most successful, since we’re only starting to reach the threshold where cars become truly autonomous. But once we get there, what will the transition to AVs actually look like?

For one thing, passenger cars will likely be one of the last vehicle types to see widespread autonomous adoption. Long-haul trucking will probably be the first sector, followed by deliveries. When you finally do step into an AV, it will likely be a taxi or a rental car. (Rental car companies lose a lot of money every year to driver-caused accidents, so they’re eager to transition to an AV fleet that is—at least in theory—less accident-prone.)

As AVs become more common, we’re going to have to rethink many of the systems we’ve created to support driving. Car insurance is a great example. Who is responsible when an autonomous vehicle gets in an accident, the person riding in the car or the company that programmed the software? Governments will have to create new laws and regulations. Roads might even have to change. A lot of highways have high-occupancy lanes to encourage carpooling—will we one day have “autonomous vehicles only” lanes? Will AVs eventually become so popular that you have to use the “human drivers only” lane if you want to be behind the wheel?

That type of shift is likely decades away, if it happens at all. Even once the technology is perfected, people might not feel comfortable riding in a car without a steering wheel at first. But I believe the benefits will convince them. AVs will eventually become cheaper than regular vehicles. And if you commute by car like me, just think about how much time you waste driving. You could instead catch up on emails, or read a good book, or watch the new episode of your favorite show—all things that are possible in fully autonomous vehicles. More importantly, AVs will help create more equity for the elderly and people with disabilities by providing them with more transportation options. And they’ll even help us avoid a climate disaster, since the majority in development are also electric vehicles.

Humanity has adapted to new modes of transportation before. I believe we will do it again. For most of our existence, we relied on natural ways of getting around: We walked, or rode on horseback, or traveled in a boat pushed by wind. Then, in the 1700s, we entered the locomotion age when mobility was powered by steam engines and internal combustion. Now, we find ourselves in the early days of the autonomous age. It’s an exciting time, and I can’t wait to see what new possibilities it unlocks.

The future of agents

AI is about to completely change how you use computers

And upend the software industry.

I still love software as much today as I did when Paul Allen and I started Microsoft. But—even though it has improved a lot in the decades since then—in many ways, software is still pretty dumb.

To do any task on a computer, you have to tell your device which app to use. You can use Microsoft Word and Google Docs to draft a business proposal, but they can’t help you send an email, share a selfie, analyze data, schedule a party, or buy movie tickets. And even the best sites have an incomplete understanding of your work, personal life, interests, and relationships and a limited ability to use this information to do things for you. That’s the kind of thing that is only possible today with another human being, like a close friend or personal assistant.

In the next five years, this will change completely. You won’t have to use different apps for different tasks. You’ll simply tell your device, in everyday language, what you want to do. And depending on how much information you choose to share with it, the software will be able to respond personally because it will have a rich understanding of your life. In the near future, anyone who’s online will be able to have a personal assistant powered by artificial intelligence that’s far beyond today’s technology.

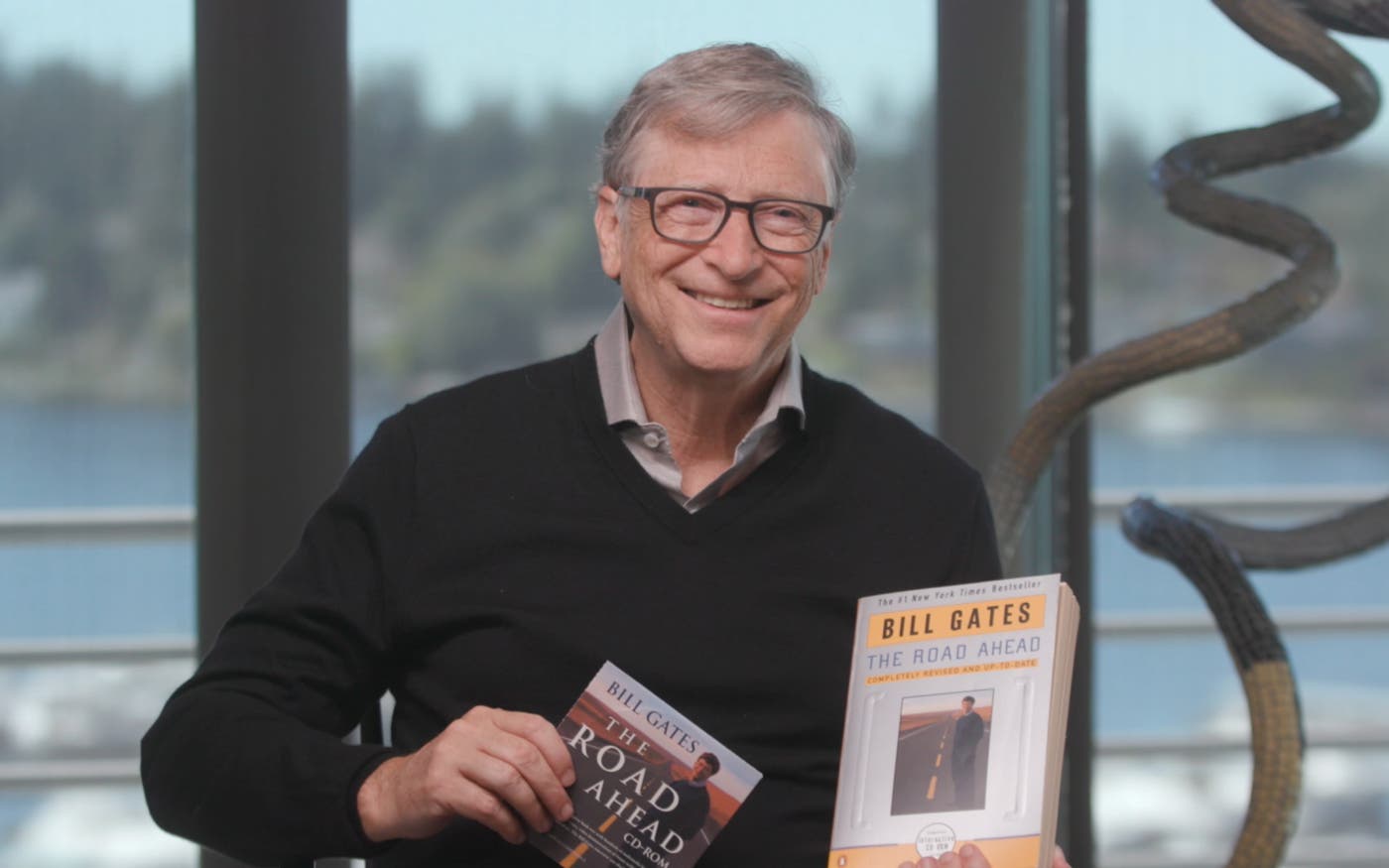

This type of software—something that responds to natural language and can accomplish many different tasks based on its knowledge of the user—is called an agent. I’ve been thinking about agents for nearly 30 years and wrote about them in my 1995 book The Road Ahead, but they’ve only recently become practical because of advances in AI.

Agents are not only going to change how everyone interacts with computers. They’re also going to upend the software industry, bringing about the biggest revolution in computing since we went from typing commands to tapping on icons.

A personal assistant for everyone

Some critics have pointed out that software companies have offered this kind of thing before, and users didn’t exactly embrace them. (People still joke about Clippy, the digital assistant that we included in Microsoft Office and later dropped.) Why will people use agents?

The answer is that they’ll be dramatically better. You’ll be able to have nuanced conversations with them. They will be much more personalized, and they won’t be limited to relatively simple tasks like writing a letter. Clippy has as much in common with agents as a rotary phone has with a mobile device.

An agent will be able to help you with all your activities if you want it to. With permission to follow your online interactions and real-world locations, it will develop a powerful understanding of the people, places, and activities you engage in. It will get your personal and work relationships, hobbies, preferences, and schedule. You’ll choose how and when it steps in to help with something or ask you to make a decision.

To see the dramatic change that agents will bring, let’s compare them to the AI tools available today. Most of these are bots. They’re limited to one app and generally only step in when you write a particular word or ask for help. Because they don’t remember how you use them from one time to the next, they don’t get better or learn any of your preferences. Clippy was a bot, not an agent.

Agents are smarter. They’re proactive—capable of making suggestions before you ask for them. They accomplish tasks across applications. They improve over time because they remember your activities and recognize intent and patterns in your behavior. Based on this information, they offer to provide what they think you need, although you will always make the final decisions.

Imagine that you want to plan a trip. A travel bot will identify hotels that fit your budget. An agent will know what time of year you’ll be traveling and, based on its knowledge about whether you always try a new destination or like to return to the same place repeatedly, it will be able to suggest locations. When asked, it will recommend things to do based on your interests and propensity for adventure, and it will book reservations at the types of restaurants you would enjoy. If you want this kind of deeply personalized planning today, you need to pay a travel agent and spend time telling them what you want.

The most exciting impact of AI agents is the way they will democratize services that today are too expensive for most people. They’ll have an especially big influence in four areas: health care, education, productivity, and entertainment and shopping.

Health care

Today, AI’s main role in healthcare is to help with administrative tasks. Abridge, Nuance DAX, and Nabla Copilot, for example, can capture audio during an appointment and then write up notes for the doctor to review.

The real shift will come when agents can help patients do basic triage, get advice about how to deal with health problems, and decide whether they need to seek treatment. These agents will also help healthcare workers make decisions and be more productive. (Already, apps like Glass Health can analyze a patient summary and suggest diagnoses for the doctor to consider.) Helping patients and healthcare workers will be especially beneficial for people in poor countries, where many never get to see a doctor at all.

These clinician-agents will be slower than others to roll out because getting things right is a matter of life and death. People will need to see evidence that health agents are beneficial overall, even though they won’t be perfect and will make mistakes. Of course, humans make mistakes too, and having no access to medical care is also a problem.

Mental health care is another example of a service that agents will make available to virtually everyone. Today, weekly therapy sessions seem like a luxury. But there is a lot of unmet need, and many people who could benefit from therapy don’t have access to it. For example, RAND found that half of all U.S. military veterans who need mental health care don’t get it.

AI agents that are well trained in mental health will make therapy much more affordable and easier to get. Wysa and Youper are two of the early chatbots here. But agents will go much deeper. If you choose to share enough information with a mental health agent, it will understand your life history and your relationships. It’ll be available when you need it, and it will never get impatient. It could even, with your permission, monitor your physical responses to therapy through your smart watch—like if your heart starts to race when you’re talking about a problem with your boss—and suggest when you should see a human therapist.

Education

For decades, I’ve been excited about all the ways that software would make teachers’ jobs easier and help students learn. It won’t replace teachers, but it will supplement their work—personalizing the work for students and liberating teachers from paperwork and other tasks so they can spend more time on the most important parts of the job. These changes are finally starting to happen in a dramatic way.

The current state of the art is Khanmigo, a text-based bot created by Khan Academy. It can tutor students in math, science, and the humanities—for example, it can explain the quadratic formula and create math problems to practice on. It can also help teachers do things like write lesson plans. I’ve been a fan and supporter of Sal Khan’s work for a long time and recently had him on my podcast to talk about education and AI.

But text-based bots are just the first wave—agents will open up many more learning opportunities.

For example, few families can pay for a tutor who works one-on-one with a student to supplement their classroom work. If agents can capture what makes a tutor effective, they’ll unlock this supplemental instruction for everyone who wants it. If a tutoring agent knows that a kid likes Minecraft and Taylor Swift, it will use Minecraft to teach them about calculating the volume and area of shapes, and Taylor’s lyrics to teach them about storytelling and rhyme schemes. The experience will be far richer—with graphics and sound, for example—and more personalized than today’s text-based tutors.

Productivity

There’s already a lot of competition in this field. Microsoft is making its Copilot part of Word, Excel, Outlook, and other services. Google is doing similar things with Assistant with Bard and its productivity tools. These copilots can do a lot—such as turn a written document into a slide deck, answer questions about a spreadsheet using natural language, and summarize email threads while representing each person’s point of view.

Agents will do even more. Having one will be like having a person dedicated to helping you with various tasks and doing them independently if you want. If you have an idea for a business, an agent will help you write up a business plan, create a presentation for it, and even generate images of what your product might look like. Companies will be able to make agents available for their employees to consult directly and be part of every meeting so they can answer questions.

Whether you work in an office or not, your agent will be able to help you in the same way that personal assistants support executives today. If your friend just had surgery, your agent will offer to send flowers and be able to order them for you. If you tell it you’d like to catch up with your old college roommate, it will work with their agent to find a time to get together, and just before you arrive, it will remind you that their oldest child just started college at the local university.

Entertainment and shopping

Already, AI can help you pick out a new TV and recommend movies, books, shows, and podcasts. Likewise, a company I’ve invested in, recently launched Pix, which lets you ask questions (“Which Robert Redford movies would I like and where can I watch them?”) and then makes recommendations based on what you’ve liked in the past. Spotify has an AI-powered DJ that not only plays songs based on your preferences but talks to you and can even call you by name.

Agents won’t simply make recommendations; they’ll help you act on them. If you want to buy a camera, you’ll have your agent read all the reviews for you, summarize them, make a recommendation, and place an order for it once you’ve made a decision. If you tell your agent that you want to watch Star Wars, it will know whether you’re subscribed to the right streaming service, and if you aren’t, it will offer to sign you up. And if you don’t know what you’re in the mood for, it will make customized suggestions and then figure out how to play the movie or show you choose.

You’ll also be able to get news and entertainment that’s been tailored to your interests. CurioAI, which creates a custom podcast on any subject you ask about, is a glimpse of what’s coming.

A shock wave in the tech industry

In short, agents will be able to help with virtually any activity and any area of life. The ramifications for the software business and for society will be profound.

In the computing industry, we talk about platforms—the technologies that apps and services are built on. Android, iOS, and Windows are all platforms. Agents will be the next platform.

To create a new app or service, you won’t need to know how to write code or do graphic design. You’ll just tell your agent what you want. It will be able to write the code, design the look and feel of the app, create a logo, and publish the app to an online store. OpenAI’s launch of GPTs this week offers a glimpse into the future where non-developers can easily create and share their own assistants.

Agents will affect how we use software as well as how it’s written. They’ll replace search sites because they’ll be better at finding information and summarizing it for you. They’ll replace many e-commerce sites because they’ll find the best price for you and won’t be restricted to just a few vendors. They’ll replace word processors, spreadsheets, and other productivity apps. Businesses that are separate today—search advertising, social networking with advertising, shopping, productivity software—will become one business.

I don’t think any single company will dominate the agents business--there will be many different AI engines available. Today, agents are embedded in other software like word processors and spreadsheets, but eventually they’ll operate on their own. Although some agents will be free to use (and supported by ads), I think you’ll pay for most of them, which means companies will have an incentive to make agents work on your behalf and not an advertiser’s. If the number of companies that have started working on AI just this year is any indication, there will be an exceptional amount of competition, which will make agents very inexpensive.

But before the sophisticated agents I’m describing become a reality, we need to confront a number of questions about the technology and how we’ll use it. I’ve written before about the issues that AI raises, so I’ll focus specifically on agents here.

The technical challenges

Nobody has figured out yet what the data structure for an agent will look like. To create personal agents, we need a new type of database that can capture all the nuances of your interests and relationships and quickly recall the information while maintaining your privacy. We are already seeing new ways of storing information, such as vector databases, that may be better for storing data generated by machine learning models.

Another open question is about how many agents people will interact with. Will your personal agent be separate from your therapist agent and your math tutor? If so, when will you want them to work with each other and when should they stay in their lanes?

How will you interact with your agent? Companies are exploring various options including apps, glasses, pendants, pins, and even holograms. All of these are possibilities, but I think the first big breakthrough in human-agent interaction will be earbuds. If your agent needs to check in with you, it will speak to you or show up on your phone. (“Your flight is delayed. Do you want to wait, or can I help rebook it?”) If you want, it will monitor sound coming into your ear and enhance it by blocking out background noise, amplifying speech that’s hard to hear, or making it easier to understand someone who’s speaking with a heavy accent.

There are other challenges too. There isn’t yet a standard protocol that will allow agents to talk to each other. The cost needs to come down so agents are affordable for everyone. It needs to be easier to prompt the agent in a way that will give you the right answer. We need to prevent hallucinations, especially in areas like health where accuracy is super-important, and make sure that agents don’t harm people as a result of their biases. And we don’t want agents to be able to do things they’re not supposed to. (Although I worry less about rogue agents than about human criminals using agents for malign purposes.)

Privacy and other big questions

As all of this comes together, the issues of online privacy and security will become even more urgent than they already are. You’ll want to be able to decide what information the agent has access to, so you’re confident that your data is shared with only people and companies you choose.

But who owns the data you share with your agent, and how do you ensure that it’s being used appropriately? No one wants to start getting ads related to something they told their therapist agent. Can law enforcement use your agent as evidence against you? When will your agent refuse to do something that could be harmful to you or someone else? Who picks the values that are built into agents?

There’s also the question of how much information your agent should share. Suppose you want to see a friend: If your agent talks to theirs, you don’t want it to say, "Oh, she’s seeing other friends on Tuesday and doesn’t want to include you.” And if your agent helps you write emails for work, it will need to know that it shouldn’t use personal information about you or proprietary data from a previous job.

Many of these questions are already top-of-mind for the tech industry and legislators. I recently participated in a forum on AI with other technology leaders that was organized by Sen. Chuck Schumer and attended by many U.S. senators. We shared ideas about these and other issues and talked about the need for lawmakers to adopt strong legislation.

But other issues won’t be decided by companies and governments. For example, agents could affect how we interact with friends and family. Today, you can show someone that you care about them by remembering details about their life—say, their birthday. But when they know your agent likely reminded you about it and took care of sending flowers, will it be as meaningful for them?

In the distant future, agents may even force humans to face profound questions about purpose. Imagine that agents become so good that everyone can have a high quality of life without working nearly as much. In a future like that, what would people do with their time? Would anyone still want to get an education when an agent has all the answers? Can you have a safe and thriving society when most people have a lot of free time on their hands?

But we’re a long way from that point. In the meantime, agents are coming. In the next few years, they will utterly change how we live our lives, online and off.

Nuts and bolts

The start-ups making robots a reality

Here’s why I’m excited about the potential of robotics technology.

Is it harder for machines to mimic the way humans move or the way humans think? If you had asked me this question a decade ago, my answer would have been “think.” So much of how the brain works is still a mystery. And yet, in just the last year, advancements in artificial intelligence have resulted in computer programs that can create, calculate, process, understand, decide, recognize patterns, and continue learning in ways that resemble our own.

Building machines that operate like our bodies—that walk, jump, touch, hold, squeeze, grip, climb, slice, and reach like we do (or better)—would seem to be an easier feat in comparison. Surprisingly, it hasn’t been. Many robots still struggle to perform basic human tasks that require the dexterity, mobility, and cognition most of us take for granted.

But if we get the technology right, the uses for robots will be almost limitless: Robots can help during natural disasters when first responders would otherwise have to put their lives on the line—or during public health crises like the COVID pandemic, when in-person interactions might spread disease. On farms, they can be used instead of toxic chemical herbicides to manually pull weeds. They can work long days lugging hundred- or thousand-pound loads around factory floors. A good enough robotic arm will also be invaluable as a prosthesis.

I understand concerns about robots taking people’s jobs, an unfortunate consequence of almost every new innovation—including the internet, which (for example) turned everyone into a travel agent and eliminated much of the vacation-planning industry. If robots have a similar impact on employment, governments and the private sector will have to help people navigate the transition. But given present labor shortages in our economy and the dangerous or unrewarding nature of certain professions, I believe it’s less likely that robots replace us in jobs we love and more likely that they’ll do work people don’t want to be doing. In the process, they can make us safer, healthier, more productive, and even less lonely.

That’s why I’m so excited about the companies across the country and around the world that are at the forefront of robotics technology, working to usher in a robotics revolution. Some of their robots are humanoid or human-like—constructed so they can interact easily in environments built for people. Others have super-human traits like flight or extendable arms that can supplement an ordinary person’s abilities. Some move around on legs. Others have wheels. Some navigate using sensors. Others are operated by remote controls.

Despite their differences, though, one thing is certain: In healthcare, hospitality, agriculture, manufacturing, construction, and even our homes, robots have the potential to transform the way we live and work. In fact, a few of them already are.

Here are some of the cutting-edge robotics start-ups and labs that I’m excited about:

Agility Robotics

If we want robots to operate in our environments as seamlessly as possible, perhaps those robots should be modeled after people. That’s what Oregon-based Agility Robotics decided when creating Digit, what they call the “first human-centric, multi-purpose robot made for logistics work.” It’s roughly the same size as a person—it’s designed to work with people, go where we go, and operate in our workflows—but it’s able to carry much heavier loads and extend its “arms” to reach shelves we’d need ladders for.

Tevel

For farmers in some rich countries, around 40 percent of costs can come from labor—with workers spending entire days out in the hot sun and then stopping at night. But given the labor shortage in agriculture, farms often have to throw away fruit that’s not harvested in time. That’s why Tevel, founded in Tel Aviv, has created flying autonomous robots that can scan tree canopies and pick ripe apples and stone fruits around the clock, while simultaneously collecting comprehensive harvesting data in real time.

Apptronik

What’s more useful: multiple robots that can each do one task over and over, or one robot that can do multiple tasks and learn to do even more? To Apptronik, an Austin-based start-up that spun out of the human-centered robotics lab at the University of Texas, the answer is obvious. So they’re building “general-purpose” humanoid bi-pedal robots like Apollo, which can be programmed to do a wide array of tasks—from carrying boxes in a factory to helping out with household chores. And because it can run software from third parties, Apollo will be just a software update away from new functionalities.

RoMeLa

Building a robot that can navigate rocky and unstable terrain, and retain its balance without falling over, is no small task. But the Robotics and Mechanisms Lab, or RoMeLa, at UCLA is working on improving mobility for robots. They may have cracked the code with ARTEMIS, possibly the fastest “running” robot in the world that’s also difficult to destabilize. ARTEMIS actually competed at the RoboCup 2023, an international soccer competition held in France in July.

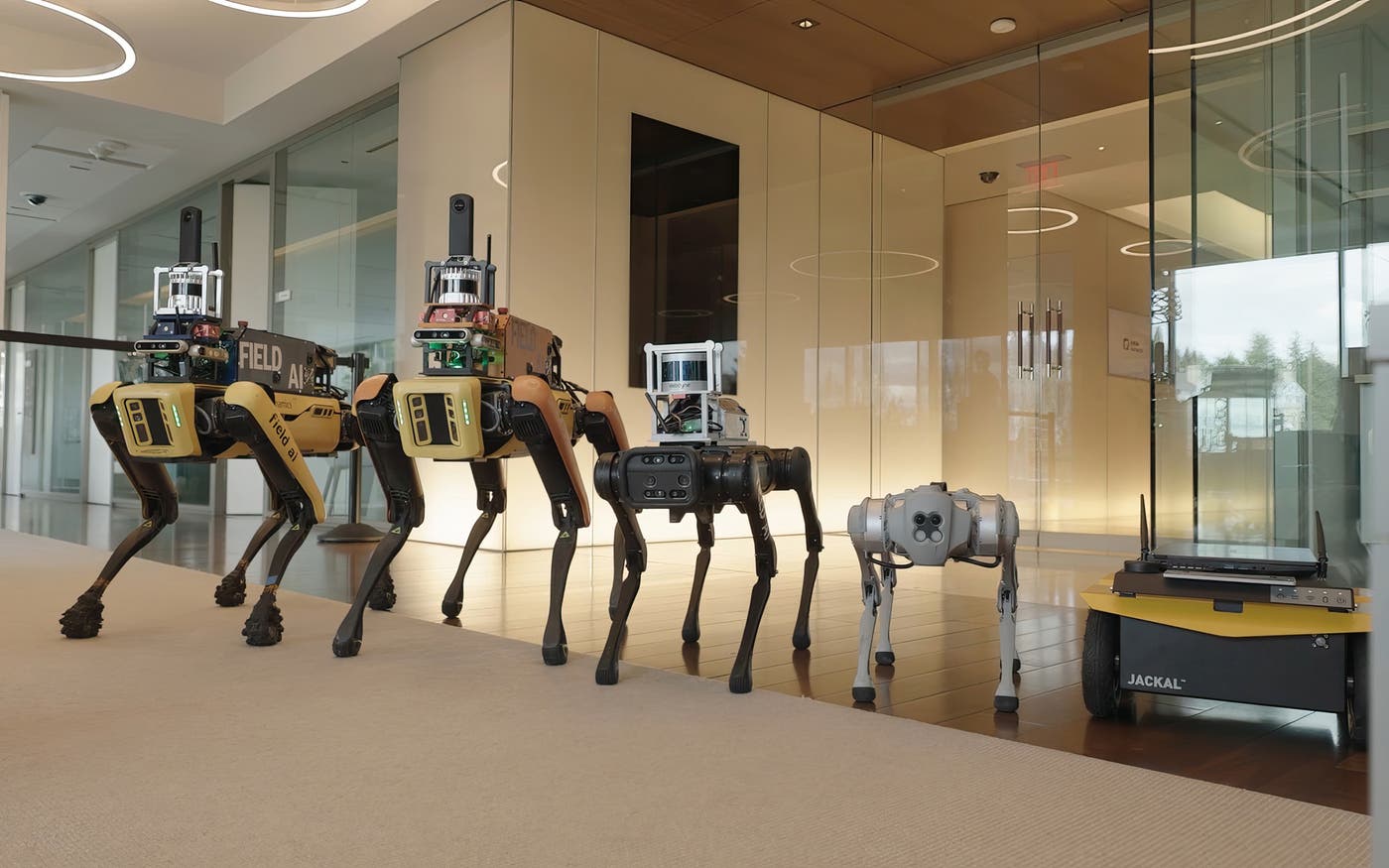

Field AI

Some robots don’t just need great “bodies”; they need great brains, too. That’s what Field AI—a robotics company based in Southern California that doesn’t build robots—is trying to create. Instead of focusing on the hardware of these machines, Field AI is developing AI software for other companies’ robots that enables them to perceive their environments, navigate without GPS (on land, by water, or in the air), and even communicate with each other.

Domo arigato

Bots, britches, and bees

A Harvard robotics lab challenges popular images of robots.

When you hear the word “robot” what comes to mind? Probably a metal, humanoid machine—something like C-3PO from Star Wars, Rosie the Robot Maid from The Jetsons, or perhaps one of the menacing Terminator robots.

At a Harvard University lab, I saw some surprising inventions that challenge our popular images of robots. One robot I wore like a glove. Another you could pull on like a pair of pants. Some robots had spongy arms that could pick up the most delicate objects. And others were so tiny and light they could take to the air on paper-thin wings, like insects.

These incredible creations are powerful examples of the exciting innovation underway in the field of robotics. They were also a reminder that while science fiction writers may lead us to fear a future of Terminator-style robots, robotics discoveries have far greater potential to improve our lives. They could offer physical support and assistance, help with search and rescue efforts, and meet medical and other technological challenges.

Stepping inside of the lab of Dr. Conor Walsh, founder of Harvard’s Biodesign Lab, I met a researcher wearing a pair of robotic britches walking on a treadmill. The britches are part of an exosuit developed by Conor and his team to help restore movement for people with spinal cord injuries or movement disorders due to a stroke or disease. And for healthy people, the exosuits could help ease the physical burdens experienced by firefighters, factory workers, and soldiers.

While rigid exoskeletons have been available for many years to serve these same functions, what’s different about this exosuit is that it’s soft. Bringing together researchers from engineering, industrial design, apparel, and medical fields, Conor and his team developed specially designed clothing that enhances performance while also being light enough that it won’t tire out users.

Another of Conor’s inventions is a soft robotic glove, which he invited me to try on. The black glove was supported with pneumatic tubes which gently assisted me with my grip as a I tried to pick up a coffee mug. This technology could be a life changer for people disabled because of a stroke or disease, allowing them to perform basic tasks like eating, drinking, and even writing.

I also met with Dr. Robert Wood, founder of the Harvard Microrobotics Lab. His team focuses on bio-inspired robots. His best-known invention is the RoboBee, a flying microbot that’s half the size of a paper clip and weighs less than one tenth of a gram. Some models of the RoboBee are able to transition from swimming underwater to flying in the air. They’re also working on ways for swarms of RoboBees to communicate with one another and coordinate their movements.

To be sure, it’s easy to imagine how such a small and potentially stealthy invention might be used for nefarious purposes. Robert’s team, however, envisions a future where flying microbots could play a beneficial role in agriculture, search and rescue missions, surveillance, and climate monitoring. Their research will also likely have applications to other fields. For example, the technologies developed to manufacture such small robots could be used in the medical field to make small surgical devices for endoscopic procedures.

Before any of these benefits can be realized, Robert’s team must solve some tough technical challenges. One key problem is how to power a small flying robot. Currently, each RoboBee is tethered to a thin wire hooked up to a power source. The goal is to find a way to have onboard power so each RoboBee can be autonomous. A battery that small and light is not yet available, so they are exploring ways to make their own.

Another amazing area of Robert’s research is soft robotics. His team wants to create a new type of robot that is entirely soft—with no rigid components like batteries or electronic systems. Their first creation is a 3D-printed robot—nicknamed the Octobot—which is soft, autonomous, and chemically powered. They also recently developed a soft robotic arm for use in deep-sea research. Up until now, the robotic arms on research submarines have been made of hard materials that lack the dexterity to grasp jellyfish and other fragile sea life. The new soft arms will allow underwater researchers to gently pick up delicate aquatic creatures without damaging them.

It was exciting to see the research underway at both these Harvard labs and speak with the many young students drawn to robotics. I have no doubt we’ll all be hearing more amazing discoveries from them in the years ahead. I left eager to learn more about the rapidly growing field of robotics research.

History helps

The risks of AI are real but manageable

The world has learned a lot about handling problems caused by breakthrough innovations.

The risks created by artificial intelligence can seem overwhelming. What happens to people who lose their jobs to an intelligent machine? Could AI affect the results of an election? What if a future AI decides it doesn’t need humans anymore and wants to get rid of us?

These are all fair questions, and the concerns they raise need to be taken seriously. But there’s a good reason to think that we can deal with them: This is not the first time a major innovation has introduced new threats that had to be controlled. We’ve done it before.

Whether it was the introduction of cars or the rise of personal computers and the Internet, people have managed through other transformative moments and, despite a lot of turbulence, come out better off in the end. Soon after the first automobiles were on the road, there was the first car crash. But we didn’t ban cars—we adopted speed limits, safety standards, licensing requirements, drunk-driving laws, and other rules of the road.

We’re now in the earliest stage of another profound change, the Age of AI. It’s analogous to those uncertain times before speed limits and seat belts. AI is changing so quickly that it isn’t clear exactly what will happen next. We’re facing big questions raised by the way the current technology works, the ways people will use it for ill intent, and the ways AI will change us as a society and as individuals.

In a moment like this, it’s natural to feel unsettled. But history shows that it’s possible to solve the challenges created by new technologies.

I have written before about how AI is going to revolutionize our lives. It will help solve problems—in health, education, climate change, and more—that used to seem intractable. The Gates Foundation is making it a priority, and our CEO, Mark Suzman, recently shared how he’s thinking about its role in reducing inequity.

I’ll have more to say in the future about the benefits of AI, but in this post, I want to acknowledge the concerns I hear and read most often, many of which I share, and explain how I think about them.

One thing that’s clear from everything that has been written so far about the risks of AI—and a lot has been written—is that no one has all the answers. Another thing that’s clear to me is that the future of AI is not as grim as some people think or as rosy as others think. The risks are real, but I am optimistic that they can be managed. As I go through each concern, I’ll return to a few themes:

- Many of the problems caused by AI have a historical precedent. For example, it will have a big impact on education, but so did handheld calculators a few decades ago and, more recently, allowing computers in the classroom. We can learn from what’s worked in the past.

- Many of the problems caused by AI can also be managed with the help of AI.

- We’ll need to adapt old laws and adopt new ones—just as existing laws against fraud had to be tailored to the online world.

In this post, I’m going to focus on the risks that are already present, or soon will be. I’m not dealing with what happens when we develop an AI that can learn any subject or task, as opposed to today’s purpose-built AIs. Whether we reach that point in a decade or a century, society will need to reckon with profound questions. What if a super AI establishes its own goals? What if they conflict with humanity’s? Should we even make a super AI at all?

But thinking about these longer-term risks should not come at the expense of the more immediate ones. I’ll turn to them now.

Deepfakes and misinformation generated by AI could undermine elections and democracy.

The idea that technology can be used to spread lies and untruths is not new. People have been doing it with books and leaflets for centuries. It became much easier with the advent of word processors, laser printers, email, and social networks.

AI takes this problem of fake text and extends it, allowing virtually anyone to create fake audio and video, known as deepfakes. If you get a voice message that sounds like your child saying “I’ve been kidnapped, please send $1,000 to this bank account within the next 10 minutes, and don’t call the police,” it’s going to have a horrific emotional impact far beyond the effect of an email that says the same thing.

On a bigger scale, AI-generated deepfakes could be used to try to tilt an election. Of course, it doesn’t take sophisticated technology to sow doubt about the legitimate winner of an election, but AI will make it easier.

There are already phony videos that feature fabricated footage of well-known politicians. Imagine that on the morning of a major election, a video showing one of the candidates robbing a bank goes viral. It’s fake, but it takes news outlets and the campaign several hours to prove it. How many people will see it and change their votes at the last minute? It could tip the scales, especially in a close election.

When OpenAI co-founder Sam Altman testified before a U.S. Senate committee recently, Senators from both parties zeroed in on AI’s impact on elections and democracy. I hope this subject continues to move up everyone’s agenda.

We certainly have not solved the problem of misinformation and deepfakes. But two things make me guardedly optimistic. One is that people are capable of learning not to take everything at face value. For years, email users fell for scams where someone posing as a Nigeran prince promised a big payoff in return for sharing your credit card number. But eventually, most people learned to look twice at those emails. As the scams got more sophisticated, so did many of their targets. We’ll need to build the same muscle for deepfakes.

The other thing that makes me hopeful is that AI can help identify deepfakes as well as create them. Intel, for example, has developed a deepfake detector, and the government agency DARPA is working on technology to identify whether video or audio has been manipulated.

This will be a cyclical process: Someone finds a way to detect fakery, someone else figures out how to counter it, someone else develops counter-countermeasures, and so on. It won’t be a perfect success, but we won’t be helpless either.

AI makes it easier to launch attacks on people and governments.

Today, when hackers want to find exploitable flaws in software, they do it by brute force—writing code that bangs away at potential weaknesses until they discover a way in. It involves going down a lot of blind alleys, which means it takes time and patience.

Security experts who want to counter hackers have to do the same thing. Every software patch you install on your phone or laptop represents many hours of searching, by people with good and bad intentions alike.

AI models will accelerate this process by helping hackers write more effective code. They’ll also be able to use public information about individuals, like where they work and who their friends are, to develop phishing attacks that are more advanced than the ones we see today.

The good news is that AI can be used for good purposes as well as bad ones. Government and private-sector security teams need to have the latest tools for finding and fixing security flaws before criminals can take advantage of them. I hope the software security industry will expand the work they’re already doing on this front—it ought to be a top concern for them.

This is also why we should not try to temporarily keep people from implementing new developments in AI, as some have proposed. Cyber-criminals won’t stop making new tools. Nor will people who want to use AI to design nuclear weapons and bioterror attacks. The effort to stop them needs to continue at the same pace.

There’s a related risk at the global level: an arms race for AI that can be used to design and launch cyberattacks against other countries. Every government wants to have the most powerful technology so it can deter attacks from its adversaries. This incentive to not let anyone get ahead could spark a race to create increasingly dangerous cyber weapons. Everyone would be worse off.

That’s a scary thought, but we have history to guide us. Although the world’s nuclear nonproliferation regime has its faults, it has prevented the all-out nuclear war that my generation was so afraid of when we were growing up. Governments should consider creating a global body for AI similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

AI will take away people’s jobs.

In the next few years, the main impact of AI on work will be to help people do their jobs more efficiently. That will be true whether they work in a factory or in an office handling sales calls and accounts payable. Eventually, AI will be good enough at expressing ideas that it will be able to write your emails and manage your inbox for you. You’ll be able to write a request in plain English, or any other language, and generate a rich presentation on your work.

As I argued in my February post, it’s good for society when productivity goes up. It gives people more time to do other things, at work and at home. And the demand for people who help others—teaching, caring for patients, and supporting the elderly, for example—will never go away. But it is true that some workers will need support and retraining as we make this transition into an AI-powered workplace. That’s a role for governments and businesses, and they’ll need to manage it well so that workers aren’t left behind—to avoid the kind of disruption in people’s lives that has happened during the decline of manufacturing jobs in the United States.

Also, keep in mind that this is not the first time a new technology has caused a big shift in the labor market. I don’t think AI’s impact will be as dramatic as the Industrial Revolution, but it certainly will be as big as the introduction of the PC. Word processing applications didn’t do away with office work, but they changed it forever. Employers and employees had to adapt, and they did. The shift caused by AI will be a bumpy transition, but there is every reason to think we can reduce the disruption to people’s lives and livelihoods.

AI inherits our biases and makes things up.

Hallucinations—the term for when an AI confidently makes some claim that simply is not true—usually happen because the machine doesn’t understand the context for your request. Ask an AI to write a short story about taking a vacation to the moon and it might give you a very imaginative answer. But ask it to help you plan a trip to Tanzania, and it might try to send you to a hotel that doesn’t exist.

Another risk with artificial intelligence is that it reflects or even worsens existing biases against people of certain gender identities, races, ethnicities, and so on.

To understand why hallucinations and biases happen, it’s important to know how the most common AI models work today. They are essentially very sophisticated versions of the code that allows your email app to predict the next word you’re going to type: They scan enormous amounts of text—just about everything available online, in some cases—and analyze it to find patterns in human language.

When you pose a question to an AI, it looks at the words you used and then searches for chunks of text that are often associated with those words. If you write “list the ingredients for pancakes,” it might notice that the words “flour, sugar, salt, baking powder, milk, and eggs” often appear with that phrase. Then, based on what it knows about the order in which those words usually appear, it generates an answer. (AI models that work this way are using what's called a transformer. GPT-4 is one such model.)

This process explains why an AI might experience hallucinations or appear to be biased. It has no context for the questions you ask or the things you tell it. If you tell one that it made a mistake, it might say, “Sorry, I mistyped that.” But that’s a hallucination—it didn’t type anything. It only says that because it has scanned enough text to know that “Sorry, I mistyped that” is a sentence people often write after someone corrects them.

Similarly, AI models inherit whatever prejudices are baked into the text they’re trained on. If one reads a lot about, say, physicians, and the text mostly mentions male doctors, then its answers will assume that most doctors are men.

Although some researchers think hallucinations are an inherent problem, I don’t agree. I’m optimistic that, over time, AI models can be taught to distinguish fact from fiction. OpenAI, for example, is doing promising work on this front.

Other organizations, including the Alan Turing Institute and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, are working on the bias problem. One approach is to build human values and higher-level reasoning into AI. It’s analogous to the way a self-aware human works: Maybe you assume that most doctors are men, but you’re conscious enough of this assumption to know that you have to intentionally fight it. AI can operate in a similar way, especially if the models are designed by people from diverse backgrounds.

Finally, everyone who uses AI needs to be aware of the bias problem and become an informed user. The essay you ask an AI to draft could be as riddled with prejudices as it is with factual errors. You’ll need to check your AI’s biases as well as your own.

Students won’t learn to write because AI will do the work for them.

Many teachers are worried about the ways in which AI will undermine their work with students. In a time when anyone with Internet access can use AI to write a respectable first draft of an essay, what’s to keep students from turning it in as their own work?

There are already AI tools that are learning to tell whether something was written by a person or by a computer, so teachers can tell when their students aren’t doing their own work. But some teachers aren’t trying to stop their students from using AI in their writing—they’re actually encouraging it.

In January, a veteran English teacher named Cherie Shields wrote an article in Education Week about how she uses ChatGPT in her classroom. It has helped her students with everything from getting started on an essay to writing outlines and even giving them feedback on their work.

“Teachers will have to embrace AI technology as another tool students have access to,” she wrote. “Just like we once taught students how to do a proper Google search, teachers should design clear lessons around how the ChatGPT bot can assist with essay writing. Acknowledging AI’s existence and helping students work with it could revolutionize how we teach.” Not every teacher has the time to learn and use a new tool, but educators like Cherie Shields make a good argument that those who do will benefit a lot.

It reminds me of the time when electronic calculators became widespread in the 1970s and 1980s. Some math teachers worried that students would stop learning how to do basic arithmetic, but others embraced the new technology and focused on the thinking skills behind the arithmetic.

There’s another way that AI can help with writing and critical thinking. Especially in these early days, when hallucinations and biases are still a problem, educators can have AI generate articles and then work with their students to check the facts. Education nonprofits like Khan Academy and OER Project, which I fund, offer teachers and students free online tools that put a big emphasis on testing assertions. Few skills are more important than knowing how to distinguish what’s true from what’s false.

We do need to make sure that education software helps close the achievement gap, rather than making it worse. Today’s software is mostly geared toward empowering students who are already motivated. It can develop a study plan for you, point you toward good resources, and test your knowledge. But it doesn’t yet know how to draw you into a subject you’re not already interested in. That’s a problem that developers will need to solve so that students of all types can benefit from AI.

What’s next?

I believe there are more reasons than not to be optimistic that we can manage the risks of AI while maximizing their benefits. But we need to move fast.

Governments need to build up expertise in artificial intelligence so they can make informed laws and regulations that respond to this new technology. They’ll need to grapple with misinformation and deepfakes, security threats, changes to the job market, and the impact on education. To cite just one example: The law needs to be clear about which uses of deepfakes are legal and about how deepfakes should be labeled so everyone understands when something they’re seeing or hearing is not genuine

Political leaders will need to be equipped to have informed, thoughtful dialogue with their constituents. They’ll also need to decide how much to collaborate with other countries on these issues versus going it alone.

In the private sector, AI companies need to pursue their work safely and responsibly. That includes protecting people’s privacy, making sure their AI models reflect basic human values, minimizing bias, spreading the benefits to as many people as possible, and preventing the technology from being used by criminals or terrorists. Companies in many sectors of the economy will need to help their employees make the transition to an AI-centric workplace so that no one gets left behind. And customers should always know when they’re interacting with an AI and not a human.

Finally, I encourage everyone to follow developments in AI as much as possible. It’s the most transformative innovation any of us will see in our lifetimes, and a healthy public debate will depend on everyone being knowledgeable about the technology, its benefits, and its risks. The benefits will be massive, and the best reason to believe that we can manage the risks is that we have done it before.

Unlimited

Bionic arms empower kids to express themselves

I recently visited a company that aims to revolutionize the way the world thinks about artificial limbs.

From pitching a fastball to painting a masterpiece, the human arm is amazing in terms of all the things it can do. But I had a new appreciation for what an incredible feat of engineering—and art—the arm is when I visited a non-profit dedicated to designing bionic limbs for children with disabilities.

Limbitless Solutions, supported by the University of Central Florida, aims to address the needs of thousands of children who were either born without arms or lost them because of accidents or disease. Its goal is to make custom-designed bionic arms for these children as commonplace as eyeglasses and braces—and at no cost to their families.

Prosthetic arms for adults, of course, are widely available, but access for many children who need them is difficult or they are unwilling to use them, according to Albert Manero, president of Limbitless Solutions. Children complain that traditional prosthetics are heavy, uncomfortable, or often include a hook for picking things up, sometimes drawing unwanted attention and teasing from other children.

Limbitless is working to change the way the world thinks about artificial limbs. Instead of trying to mimic the look of human skin as existing prosthetics do, Limbitless’s engineers and artists work together to design and manufacture artificial limbs that are colorful and artistic. Instead of a hook, the limbs feature hands with moveable fingers that can grasp objects using the body’s own electrical signals.

The first bionic arm the Limbitless team created was an Iron Man-inspired limb for a 7-year-old boy, Alex Pring, who loves superheroes. (Robert Downey Jr. teamed up with Limbitless to deliver the bionic arm to Alex in 2015.) Other bionic arms are decorated with flowers, bright colors, and other designs inspired by the children’s interests.

The bionic arms have had a life-changing impact not only on the children’s ability to perform day-to-day tasks like getting dressed, picking things up, or buckling a seatbelt, but also their own sense of themselves. Children who were often asked, “What’s wrong with you?” find that they are now the center of attention whenever they enter a room.

During my visit to Limbitless’s offices in Orlando last year, I had the opportunity to meet Annika Emmert, a 13-year-old girl whose life was changed thanks to the work of Limbitless Solutions. Annika was born with a partially developed right arm, which drew lots of unwanted stares from other kids as she was growing up. When Annika’s parents heard about Limbitless, they reached out to Manero’s team to see if they could help Annika design her own artificial limb.

Annika proudly showed me her creation—a bionic arm painted light blue and decorated with white and pink flowers.

“I’ll wear it sometimes and everybody will want to shake my hand,” she said, “They’ll be like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s so pretty,’ kind of thing or, ‘Where’d you get it?’ and, ‘Can I get one?’”

Ahead of the curve

Sal Khan is pioneering innovation in education…again

Brave New Words paints an inspiring picture of AI in the classroom.

When Chat GPT 4.0 launched last week, people across the internet (and the world) were blown away. Talking to AI has always felt a bit surreal—but OpenAI’s latest model feels like talking to a real person. You can actually speak to it, and have it talk back to you, without lags. It’s as lifelike as any AI we’ve seen so far, and the use cases are limitless. One of the first that came to my mind was how big a game-changer it will be in the classroom. Imagine every student having a personal tutor powered by this technology.

I recently read a terrific book on this topic called Brave New Words. It’s written by my friend (and podcast guest) Sal Khan, a longtime pioneer of innovation in education. Back in 2006, Sal founded Khan Academy to share the tutoring content he’d created for younger family members with a wider audience. Since then, his online educational platform has helped teach over 150 million people worldwide—including me and my kids.

Well before this recent AI boom, I considered him a visionary. When I learned he was writing this book, I couldn’t wait to read it. Like I expected, Brave New Words is a masterclass.

Chapter by chapter, Sal takes readers through his predictions—some have already come true since the book was written—for AI’s many applications in education. His main argument: AI will radically improve both student outcomes and teacher experiences, and help usher in a future where everyone has access to a world-class education.

You might be skeptical, especially if you—like me—have been following the EdTech movement for a while. For decades, exciting technologies and innovations have made headlines, accompanied by similarly bold promises to revolutionize learning and teaching as we know it—only to make a marginal impact in the classroom.

But drawing on his experience creating Khanmigo, an AI-powered tutor, Sal makes a compelling case that AI-powered technologies will be different. That’s because we finally have a way to give every student the kind of personalized learning, support, and guidance that’s historically been out of reach for most kids in most classrooms. As Sal puts it, “Getting every student a dedicated on-call human tutor is cost prohibitive.” AI tutors, on the other hand, aren’t.

Picture this: You're a seventh-grade student who struggles to keep up in math. But now, you have an AI tutor like the one Sal describes by your side. As you work through a challenging set of fraction problems, it won’t just give you the answer—it breaks each problem down into digestible steps. When you get stuck, it gives you easy-to-understand explanations and a gentle nudge in the right direction. When you finally get the answer, it generates targeted practice questions that help build your understanding and confidence.

And with the help of an AI tutor, the past comes to life in remarkable ways. While learning about Abraham Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War, you can have a “conversation” with the 16th president himself. (As Sal demonstrates in the book, conversations with one of my favorite literary figures, Jay Gatsby, are also an option.)

When the time comes to write your essay, don’t worry about the dreaded blank page. Instead, your AI tutor asks you thought-starters to help brainstorm. You get feedback on your outline in seconds, with tips to improve the logic or areas where you need more research. As you draft, the tutor evaluates your writing in real-time—almost impossible without this technology—and shows where you might clarify your ideas, provide more evidence, or address a counterargument. Before you submit, it gives detailed suggestions to refine your language and sharpen your points.

Is this cheating?

It’s a complicated question, and there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Sal notes that bouncing ideas off friends, asking family members to critique work, and using spellcheckers and tools like Grammarly—which can rephrase entire sentences—aren’t considered cheating today by most measures. Similarly, when used right, AI doesn’t work for students but with them to move something forward that they might otherwise get stuck on. That’s why, according to Sal, a lot of educators who first banned AI from class are now encouraging students to use it.

After all, mastery of AI won’t just be nice to have in a few years—for many professions, it’ll be necessary. Employees who can use AI effectively will be far more valuable than those who can’t. By incorporating this technology into education, we're both improving students’ experiences and outcomes and preparing them for the jobs of the future—which will become more enjoyable and fulfilling with AI in the mix.

That includes teaching. With every transformative innovation, there are fears of machines taking jobs. But when it comes to education, I agree with Sal: AI tools and tutors never can and never should replace teachers. What AI can do, though, is support and empower them.

Until now, most EdTech solutions, as great as they may be, haven’t meaningfully made teachers’ lives easier. But with AI, they can have a superhuman teaching assistant to handle routine tasks like lesson planning and grading—which take up almost half of a typical teacher's day. In seconds, an AI assistant can grade spelling tests or create a lesson plan connecting the Industrial Revolution to current events. It can even monitor each student's progress and give teachers instant feedback, allowing for a new era of personalized learning.

With AI assistants handling the mundane stuff, teachers can focus on what they do best: inspiring students, building relationships, and making sure everyone feels seen and supported—especially kids who need a little extra help.

Of course, there are challenges involved in bringing AI into schools at scale, and Sal is candid about them. We need systems that protect student privacy and mitigate biases. And there’s still a lot to do so that every kid has access to the devices and connectivity they need to use AI in the first place. No technology is a silver bullet for education. But I believe AI can be a game-changer and great equalizer in the classroom, the workforce, and beyond.

I recently visited First Avenue School in Newark, New Jersey, where Khanmigo is currently being piloted. We’re still in the early days, but it was amazing to see firsthand how AI can be used in the classroom—and to speak with students and teachers who are already reaping the benefits. It felt like catching a glimpse of the future. No one understands where education is headed better than Sal Khan, and I can't recommend Brave New Words enough.

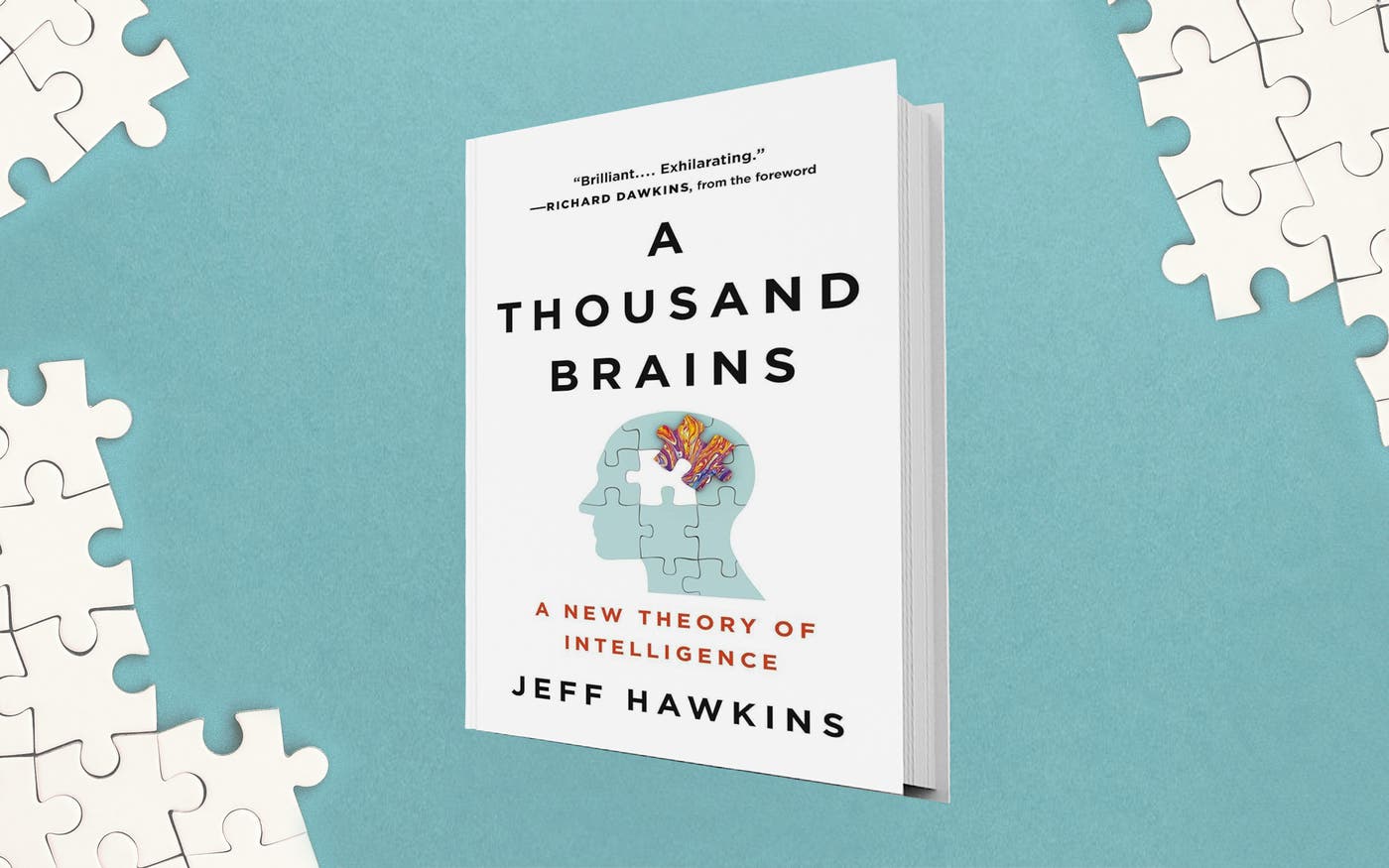

Gray matter matters

Is this how your brain works?

Jeff Hawkins’s book explores a new theory about human intelligence.

Of all the subjects I’ve been learning about lately, one stands out for its mind-boggling complexity: understanding how the cells and connections in our brains give rise to consciousness and our ability to learn.

Thanks to better instruments for observing brain activity, faster genetic sequencing, and other technological improvements, we’ve learned a lot in recent years. For example, we now understand more about the different types of neurons that make up the brain, how neurons communicate with one another, and which neurons are active when we’re performing all kinds of tasks. As a result, many people call this the golden era of neuroscience.

But let’s put this progress in context. We’re only beginning to understand how a worm’s brain works—and it has only 300 neurons, compared with our 86 billion. So you can imagine how far we are from getting answers to the really big, important questions about brain function, including what causes neurodegeneration and how we can block it. Watching helplessly as my dad declined from Alzheimer’s made me feel as if this era is not yet a golden era. I think it’s more like an early dawn.

Over the years, I’ve read quite a few books about the brain, most of them written by academic neuroscientists who view it through the lens of sophisticated lab experiments. Recently, I picked up a brain book that’s much more theoretical. It’s called A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, by a tech entrepreneur named Jeff Hawkins.

I got to know Hawkins in the 1990s, when he was one of the pioneers of mobile computing and co-inventor of the PalmPilot. After his tech career, he decided to work with a singular focus on just one problem: making big improvements in machine learning. His platform for doing that is a Silicon Valley–based company called Numenta, which he founded in 2005.

Machine learning has incredible promise. I believe that in the coming decades we will produce machines that have the kind of broad, flexible “general intelligence” that would enable them to help us address truly complex, multifaceted challenges like improving medicine through a more advanced understanding of how proteins fold. Nothing we call AI today has anything like that kind of intelligence.

As Hawkins puts it, “There is no ‘I’ in AI.” Computers can beat a grandmaster in chess, but they don’t know that chess is a game. Hawkins argues that we can’t achieve artificial general intelligence “by doing more of what we are currently doing.” In his view, understanding much more about the part of the brain called the neocortex is key to developing true general AI, and that’s what this book is about.

A Thousand Brains is appropriate for non-experts who have little background in brain science or computer science. It’s filled with fascinating insights into the architecture of the brain and tantalizing clues about the future of intelligent machines. In the foreword, the legendary evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins says the book “will turn your mind into a maelstrom of … provocative ideas.” I agree.

Hawkins begins by walking us through the basics of the neocortex, which makes up 70 percent of the human brain. It’s responsible for almost everything we associate with intelligence, such as our ability to speak, create music, and solve complex problems.

Borrowing from the work of neuroscientist Vernon Mountcastle, Hawkins reports that the basic circuit of the neocortex is called a “cortical column,” which is divided into several hundred “minicolumns” with about a hundred individual neurons. He argues that “our quest to understand intelligence boils down to figuring out what a cortical column does and how it does it.”

He believes that the basic function of the cortical column is to make constant predictions about the world as we move through it. “With each movement, the neocortex predicts what the next sensation will be,” Hawkins writes. “If any input doesn’t match with the brain’s prediction … this alerts the neocortex that its model of that part of the world needs to be updated.”

The name of the book comes from Hawkins’s conclusion that cortical columns operate in parallel, each making separate predictions about what the next sensory input will be. In other words, each column functions as its own separate learning machine.

If Hawkins is right that the only viable path to artificial general intelligence is by replicating the workings of the neocortex, that means it’s unlikely that intelligent machines will supplant or subjugate the human race—the kind of thing you see in classic sci-fi movies like The Matrix and The Terminator. That’s because the neocortex operates differently from parts of the brain that evolved much earlier and that drive our primal emotions and instincts.

“Intelligent machines need to have a model of the world and the flexibility of behavior that comes from that model, but they don’t need to have human-like instincts for survival and procreation,” Hawkins writes. In other words, we will eventually be able to create machines that replicate the logical, rational neocortex without having to wrap it around an old brain that’s an “ignorant brute” wired for fear, greed, jealousy, and other human sins. That’s why Hawkins dismisses the notion that humans will lose control of the machines they create.

Unfortunately, we may still need to worry about the dark side of artificial intelligence. Even if intelligent machines replicate only the “new brain” and are not saddled with an “old brain,” some people will still try to use them for bad purposes. Sadly, that is human nature.

In the end, I come back to my starting premise that we’re still early in our understanding of the human brain compared with just about every other part of our world. We don’t know yet whether Hawkins’s Thousand Brains Theory will hold up to experimental scrutiny. And even if it does, we still don’t know how to replicate cortical columns with digital technologies.

All I know for sure is that I’ll be reading a lot more about this topic. My hope is that it will help lead to great breakthroughs in the way we go about solving the world’s hardest problems.

Sea change

My favorite book on AI

The Coming Wave is a clear-eyed view of the extraordinary opportunities and genuine risks ahead.

When people ask me about artificial intelligence, their questions often boil down to this: What should I be worried about, and how worried should I be? For the past year, I've responded by telling them to read The Coming Wave by Mustafa Suleyman. It’s the book I recommend more than any other on AI—to heads of state, business leaders, and anyone else who asks—because it offers something rare: a clear-eyed view of both the extraordinary opportunities and genuine risks ahead.

The author, Mustafa Suleyman, brings a unique perspective to the topic. After helping build DeepMind from a small startup into one of the most important AI companies of the past decade, he went on to found Inflection AI and now leads Microsoft’s AI division. But what makes this book special isn’t just Mustafa’s firsthand experience—it’s his deep understanding of scientific history and how technological revolutions unfold. He's a serious intellectual who can draw meaningful parallels across centuries of scientific advancement.

Most of the coverage of The Coming Wave has focused on what it has to say about artificial intelligence—which makes sense, given that it's one of the most important books on AI ever written. And there is probably no one as qualified as Mustafa to write it. He was there in 2016 when DeepMind’s AlphaGo beat the world’s top players of Go, a game far more complex than chess with 2,500 years of strategic thinking behind it, by making moves no one had ever thought of. In doing so, the AI-based computer program showed that machines could beat humans at our own game—literally—and gave Mustafa an early glimpse of what was coming.

But what sets his book apart from others is Mustafa’s insight that AI is only one part of an unprecedented convergence of scientific breakthroughs. Gene editing, DNA synthesis, and other advances in biotechnology are racing forward in parallel. As the title suggests, these changes are building like a wave far out at sea—invisible to many but gathering force. Each would be game-changing on its own; together, they’re poised to reshape every aspect of society.

The historian Yuval Noah Harari has argued that humans should figure out how to work together and establish trust before developing advanced AI. In theory, I agree. If I had a magic button that could slow this whole thing down for 30 or 40 years while humanity figures out trust and common goals, I might press it. But that button doesn’t exist. These technologies will be created regardless of what any individual or company does.

As is, progress is already accelerating as costs plummet and computing power grows. Then there are the incentives for profit and power that are driving development. Countries compete with countries, companies compete with companies, and individuals compete for glory and leadership. These forces make technological advancement essentially unstoppable—and they also make it harder to control.

In my conversations about AI, I often highlight three main risks we need to consider. First is the rapid pace of economic disruption. AI could fundamentally transform the nature of work itself and affect jobs across most industries, including white-collar roles that have traditionally been safe from automation. Second is the control problem, or the difficulty of ensuring that AI systems remain aligned with human values and interests as they become more advanced. The third risk is that when a bad actor has access to AI, they become more powerful—and more capable of conducting cyber-attacks, creating biological weapons, even compromising national security.

This last risk—of empowering bad actors—is what leads to the biggest challenge of our time: containment. How do we limit the dangers of these technologies while harnessing their benefits? This is the question at the heart of The Coming Wave, because containment is foundational to everything else. Without it, the risks of AI and biotechnology become even more acute. By solving for it first, we create the stability and trust needed to tackle everything else.

Of course, that’s easier said than done.

While previous transformative technologies like nuclear weapons could be contained through physical security and strict access controls, AI and biotech present a fundamentally different challenge. They're increasingly accessible and affordable, their development is nearly impossible to detect or monitor, and they can be used behind closed doors with minimal infrastructure. Outlawing them would mean the good guys unilaterally disarm while bad actors forge ahead anyway. And it would hurt everyone because these technologies are inherently dual-use. The same tools that could be used to create biological weapons could also cure diseases; the same AI that could be used for cyber-attacks could also strengthen cyber defense.

So how do we achieve containment in this new reality? It’s hardly fair to complain that Mustafa hasn’t single-handedly solved one of the most complex problems humanity has ever faced. Still, he lays out an agenda that’s appropriately ambitious for the scale of the challenge—ranging from technical solutions (like building an emergency off switch for AI systems) to sweeping institutional changes, including new global treaties, modernized regulatory frameworks, and historic cooperation among governments, companies, and scientists. When you finish his list of recommendations, you might wonder if we can really accomplish all this in time. But that’s precisely why this book is so important: It helps us understand the urgency while there’s still time to act.

I’ve always been an optimist, and reading The Coming Wave hasn’t changed that. I firmly believe that advances in AI and biotech could help make breakthrough treatments for deadly diseases, innovative solutions for climate change, and high-quality education for everyone a reality. But true optimism isn’t about blind faith. It’s about seeing both the upsides and the risks, then working to shape the outcomes for the better.

Whether you’re a tech enthusiast, a policymaker, or someone simply trying to understand where the world is heading, you should read this book. It won’t give you easy answers, but it will help you ask the right questions—and leave you better prepared to ride the coming wave, instead of getting swept away by it.

The Da Vinci Codescope

A new way to look at Leonardo

This one-of-a-kind device brings you closer to one of history’s greatest thinkers.

I’ve been fascinated by the artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci for decades. He had one of the most innovative minds ever. Next year is the 500th anniversary of his death, and I thought I would share a short video about a project I’ve worked on that is helping to mark the occasion.

The project is called the Codescope. It’s an interactive kiosk with a touch screen that lets you explore the Codex Leicester, a notebook of Leonardo’s that I bought in 1994. Using the Codescope, you can learn about the history of the notebook, see every page of Leonardo’s original writing, get a translation, and even watch animated versions of his drawings.

The Codex and Codescope are traveling together to various museums in Europe as part of the celebration. (They’re at the Uffizi in Florence through January 20.) Since you can’t touch the Codex itself—it’s preserved behind glass—the Codescope is the next best thing to flipping through the pages that the great man wrote on.

Rear view mirror

The Road Ahead after 25 years

The predictions I got right and wrong in my first book.

Twenty-five years ago today, I published my first book, The Road Ahead. At the time, people were wondering where digital technology was headed and how it would affect our lives, and I wanted to share my thoughts—and my enthusiasm. I also had fun making some predictions about breakthroughs in computing, and especially the Internet, that were coming in the next couple of decades.

Next February, I’ll release another book, this one about climate change. Before it hits the shelves, I thought it would be fun to look back at The Road Ahead and see how things turned out.

As I wrote in The Road Ahead, we tend to overestimate the changes that will happen in the short term and underestimate the ones that will happen over the long term. That is certainly my experience with the book itself. I was too optimistic about some things, but other things happened even faster or more dramatically than I imagined.

These days, it’s easy to forget just how much the Internet has transformed society. When The Road Ahead came out, people were still navigating with paper maps. They listened to music on CDs. Photos were developed in labs. If you needed a gift idea, you asked a friend (in person or over the phone). Today you can do every one of these things much more easily—and in most cases at a much lower cost too—using digital tools.

That’s all covered in the book (I was thinking and learning about these things obsessively back then). For instance, there’s a chapter on video on demand and computers that will fit in your pocket. You can download it here for free:

One thing I was probably too optimistic about is the rise of digital agents. It is true that we have Cortana, Siri, and Alexa, but working with them is still far from the rich experience I had in mind in 1995. They don’t yet “learn about your requirements and preferences in much the way that a human assistant does,” as I wrote at the time. We’re just at the beginning of what agents will eventually be capable of.