Solvable problems

These two brilliant economists explain hot-button issues

Good Economics for Hard Times was written about a pre-COVID world, but it’s still relevant today.

Did you know that there’s no such thing as the Nobel Prize for Economics? The economics award that most people refer to as the Nobel is an add-on, the product of a 1968 gift from a big bank celebrating its 300th anniversary. That’s why the name of the award is the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The economics prize differs from the official Nobel Prizes in another way: It honors a social science rather than a natural science. Economics is not grounded in natural laws like Newton’s law of gravitation. It’s rooted in human nature, which is notoriously hard to predict.

I think about this every time I hear about a new book on economics and consider adding it to my bookbag. I have no trouble finding books or articles written by smart economists. But I do sometimes worry that those economists won’t have appropriate humility about what economic methods can and cannot teach us, especially right now when the global economy is in an unprecedented state of extreme instability because of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Two economists who are honest about the limits of economics and don’t oversimplify are the husband-and-wife team of Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo. They’re the couple who started MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). I have always admired their rigorous, experimental approach to assessing the merits of different approaches to fighting poverty, and I loved their first book, Poor Economics (2011). So I was pleased when I learned they were going to publish a second book, Good Economics for Hard Times. Two weeks before the book hit the bookshelves, they won the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, along with their colleague Michael Kremer.

Just like the couple’s first book, their new one is easily accessible for readers who don’t have a degree in economics. And they acknowledge at the very beginning, “We, the economists, are often too wrapped up in our models and our methods and sometimes forget where science ends and ideology begins.”

In one important respect, the new book is a significant departure from their previous one. Poor Economics, as its name suggests, focused on poor countries. Good Economics for Hard Times focuses instead on the policy debates that are getting so much attention in wealthy countries. (Obviously, since it was written long before the coronavirus pandemic, it doesn’t touch on that issue.) Although it’s clear that their real expertise is microeconomics (the study of how individual people make decisions) rather than macroeconomics (the study of how an overall economy behaves), Banerjee and Duflo are good at assembling and explaining the facts behind contentious issues like immigration, inequality, and trade.

I’ll give you an example from their discussion of immigration. It turns out that the field of economics has more clarity than I realized about the effect of immigration on jobs.

You have probably heard the argument that when immigrants who are willing to work for low pay show up in a community, they trigger the reduction of wages for some percentage of the local population. But Good Economics for Hard Times shows how that concern is misplaced. “There’s no credible evidence that even relatively large inflows of low-skilled migrants hurt the local population,” Banerjee and Duflo write. “This has a lot to do with the peculiar nature of the labor market. Very little about it fits the standard story about supply and demand.”

Why doesn’t the labor market fit the standard story? Banerjee and Duflo show that migrants are not just workers; they’re also consumers. “The newcomers spend money: they go to restaurants, they get haircuts, they go shopping. This creates jobs, and mostly jobs for other low-skilled people.” Another reason is that an influx of new laborers reduces companies’ incentive to automate their operations. “The promise of a reliable supply of low-wage workers makes it less attractive to adopt labor-saving technologies.”

In contrast with immigration, economists do not have clear data or conclusions when it comes to what drives economic growth. As I noted in my reviews of Robert Gordon’s great book The Rise and Fall of American Growth and Vaclav Smil’s masterpiece Growth, I have a lot of optimism about the ways artificial intelligence and other digital tools can accelerate learning, productivity, and innovation. But that said, Banerjee and Duflo make a powerful case that it’s just about impossible to make specific predictions in this area. “Of all the things economists have tried (and mostly failed) to predict, growth is one area where we have been particularly pathetic.”

Some economists argue that there’s at least one sure-fire way to boost an economy: cutting taxes. But Banerjee and Duflo show that even the iconic version of these cuts, the major tax reform enacted under Ronald Reagan, did little if anything to accelerate growth. “There is no evidence the Reagan tax cuts, or the Clinton top marginal rate increase, or the Bush tax cuts did anything to change the long-run growth rate,” Banerjee and Duflo write.

But don’t high taxes on wealthy people like me reduce our incentive to work hard and create new jobs? The answer is no. Banerjee and Duflo found no evidence that people at the top of the income distribution change their behavior in ways that affect the overall rate of economic growth. “In a policy world that has mostly abandoned reason … let’s be clear: Tax cuts for the wealthy do not produce economic growth.” Banerjee and Duflo have given me even more reason to advocate, as I did in this recent post, for a tax system in which the rich pay more taxes than we currently do.

Banerjee and Duflo also offer good insights on what’s causing the economic despair in rural and Rust Belt America (before COVID-19). They offer a stinging critique of the financial sector and its behavior, but they find that the biggest driver of despair is the sorting that results from the expansion of global trade. “Those lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, with the right skills or the right ideas, grew wealthy, sometimes fabulously so,” they write. “For the rest … jobs were lost and not replaced…. Trade has created a more volatile world where jobs suddenly vanish only to turn up a thousand miles away.”

I’m in favor of trade, and I think Banerjee and Duflo overemphasize the role it plays in job losses and underemphasize the big role played by technological advances. But they are right that political leaders could be more honest that there are winners and losers from trade and from new technologies—and then enact smart policies to help. Sadly, “the United States [did] not come close to compensating workers who lost out,” they write.

In the end, Good Economics for Hard Times felt to me like a good complement to books that paint intimate portraits of what it’s like to grow up poor in America, including Educated, Hillbilly Elegy, and Evicted. Banerjee and Duflo use extensive data to zoom out and show us a wider view of these human dynamics. Their research is not hard science, like chemistry or physics. But I found most of it to be useful and compelling. I suspect you will too.

The new anxieties

Is there a crisis in capitalism?

A renowned economist’s thought-provoking new book.

I’m a big fan of Paul Collier. A highly respected Oxford economist (and a knight!), he has spent his career trying to understand and alleviate global poverty. His book The Bottom Billion is still on the short list of books that I recommend to people, even though a lot has changed since it was published 12 years ago.

So I was a little surprised when I learned that Collier’s latest book isn’t about poverty at all. But when I saw that it was about something I’m also keenly interested in—the polarization we’re seeing in the U.S., Europe, and other places—I was eager to see what he had to say. I’m glad I did. The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties, is an ambitious and thought-provoking book.

Collier wrestles with a tough problem. If you measure by things like GDP growth and lifespan, life is better for more people around the world than it has ever been. And yet many people are questioning the capitalist system that produced those gains. There’s an understandable sense that the system is in crisis.

Why is this happening? Collier says we’re experiencing three big rifts: 1) a spatial divide between booming cities and struggling small towns; 2) a class divide between people who have a college education and those who don’t; and 3) a global divide between high- and middle-income countries on the one hand, and fragile states on the other.

Collier has a personal perspective on all three divides. He grew up in industrial Sheffield, England; now he makes his home in an upscale college town. Both of his parents left school when they were 12; he went to Oxford. He lives in a rich country, but because of his work, he spends a lot of time in some of the poorest places in the world.

As a result of the three trends, Collier says, capitalism is delivering for some people but leaving others behind. For example, he makes a point that should feel familiar to anyone living in London, New York City, or my hometown of Seattle. Highly skilled workers have a big incentive to move to cities, where they can get high-paying jobs. When all those big earners cluster in one place, more businesses sprout up to support them. This large-scale movement into the city drives up the cost of land, making it less affordable for everyone else. It is a virtuous cycle for a lucky few and a vicious one for others.

This all adds up to a compelling description of the problem. What should we do about it?

I found myself agreeing with a lot of what Collier has to say. I was especially struck by the central idea of his book, that we need to strengthen the reciprocal obligations we have to each other. This won’t directly address the divides, but it will create the atmosphere where we can talk more about pragmatic solutions to them. “As we recognize new obligations to others,” Collier writes, “we build societies better able to flourish; as we neglect them we do the opposite…. To achieve the promise [of prosperity], our sense of mutual regard has to be rebuilt.”

He looks at four areas where we can do this: the global level, the nation-state, the company, and the family. Globally, for example, he argues that we need to revitalize groups like NATO and the EU while also recognizing the need to help the world’s poorest people escape poverty (an area that is of special interest to me given the Gates Foundation’s work).

At the corporate level, Collier criticizes the notion that a company’s only responsibility is to make money for its shareholders. This sole focus on the bottom line, he argues, means many companies no longer feel responsible to their employees or the communities where they operate. This has been a big driver, he says, of “the mass contempt in which capitalism is held—as greedy, selfish, corrupt.”

I agree that companies need to take a long-run view of their interests and not just focus on short-term profits. It matters how businesses are viewed in their communities and by their employees. I think the profit motive encourages companies to take such a broad view of their interests more often than Collier acknowledges, although there are plenty of exceptions. And when we want companies to act a certain way—for example to reduce pollution or pay a certain amount of taxes—I think it’s more effective to have the government pass laws than to expect them to voluntarily change their behavior.

If I had the chance, I would ask Collier more about this. I finished the book wondering if he thinks we can change the incentive structure so companies act differently. Or perhaps some companies don’t realize that their long-term interests require valuing things other than the bottom line. It would be fascinating to discuss with him.

I would also take Collier’s world/nation/company/family argument one step further. I would add a fifth category: community. We need to re-connect at the local level, where we’re physically close enough to help each other out in times of need. Churches can serve this purpose. So can community groups. Digital tools have also helped people connect with their neighbors, though I think there’s still more that could be done there.

With a complex subject like this, it is always easier to describe the problem than to solve it. The Future of Capitalism devotes a lot of time to how we might ease people’s anxieties, including more vocational training, support for families (what he calls “social maternalism”), and policies designed to make companies behave more ethically.

Although I don’t agree with all of Collier’s suggestions, I think he is right more often than not. Melinda and I will have more to say about inequity in our next Goalkeepers report in September. But to take just one example, I think the U.S. government needs more revenue to meet its commitments, and that means raising taxes on the wealthiest. Similarly, Collier makes a good case for raising taxes on the unearned income of high-wage workers in cities (like when the value of their land goes up simply because they can afford to live in a place where other well-off people want to live).

Ultimately, I agree with him that “capitalism needs to be managed, not defeated.” We should do more to curb its excesses and minimize its negative aspects. But no other system comes close to delivering the innovations and economic growth that capitalism has sparked around the world. This is worth remembering as we consider its future.

Can’t touch this

Not enough people are paying attention to this economic trend

Capitalism Without Capital explains how things we can’t touch are reshaping the economy.

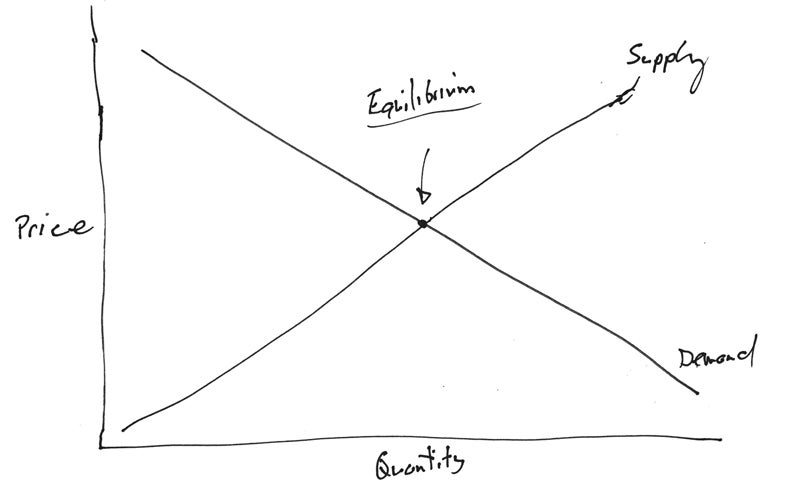

By the second semester of my freshman year at Harvard, I had started going to classes I wasn’t signed up for, and had pretty much stopped going to any of the classes I was signed up for—except for an introduction to economics class called “Ec 10.” I was fascinated by the subject, and the professor was excellent. One of the first things he taught us was the supply and demand diagram. At the time I was in college (which was longer ago than I like to admit), this was basically how the global economy worked:

There are two assumptions you can make based on this chart. The first is still more or less true today: as demand for a product goes up, supply increases, and price goes down. If the price gets too high, demand falls. The sweet spot where the two lines intersect is called equilibrium. Equilibrium is magical, because it maximizes value to society. Goods are affordable, plentiful, and profitable. Everyone wins.

The second assumption this chart makes is that the total cost of production increases as supply increases. Imagine Ford releasing a new model of car. The first car costs a bit more to create, because you have to spend money designing and testing it. But each vehicle after that requires a certain amount of materials and labor. The tenth car you build costs the same to make as the 1000thth car. The same is true for the other things that dominated the world’s economy for most of the 20 century, including agricultural products and property.

Software doesn’t work like this. Microsoft might spend a lot of money to develop the first unit of a new program, but every unit after that is virtually free to produce. Unlike the goods that powered our economy in the past, software is an intangible asset. And software isn’t the only example: data, insurance, e-books, even movies work in similar ways.

The portion of the world's economy that doesn't fit the old model just keeps getting larger. That has major implications for everything from tax law to economic policy to which cities thrive and which cities fall behind, but in general, the rules that govern the economy haven’t kept up. This is one of the biggest trends in the global economy that isn’t getting enough attention.

If you want to understand why this matters, the brilliant new book Capitalism Without Capital by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake is about as good an explanation as I’ve seen. They start by defining intangible assets as “something you can’t touch.” It sounds obvious, but it’s an important distinction because intangible industries work differently than tangible industries. Products you can’t touch have a very different set of dynamics in terms of competition and risk and how you value the companies that make them.

Haskel and Westlake outline four reasons why intangible investment behaves differently:

- It’s a sunk cost. If your investment doesn’t pan out, you don’t have physical assets like machinery that you can sell off to recoup some of your money.

- It tends to create spillovers that can be taken advantage of by rival companies. Uber’s biggest strength is its network of drivers, but it’s not uncommon to meet an Uber driver who also picks up rides for Lyft.

- It’s more scalable than a physical asset. After the initial expense of the first unit, products can be replicated ad infinitum for next to nothing.

- It’s more likely to have valuable synergies with other intangible assets. Haskel and Westlake use the iPod as an example: it combined Apple’s MP3 protocol, miniaturized hard disk design, design skills, and licensing agreements with record labels.

None of these traits are inherently good or bad. They’re just different from the way manufactured goods work.

Haskel and Westlake explain all this in a straightforward way—the book is almost written like a textbook without a lot of commentary. They don’t act like there’s something evil about the trend or prescribe hard policy solutions. Instead they take the time to convince you why this transition is important and offer broad ideas about what countries can do to keep up in a world where the “Ec 10” supply and demand chart is increasingly irrelevant.

The book is eye opening, but it’s not for everyone. Although Haskel and Westlake are good about explaining things, you need some familiarity with economics to follow what they’re saying. If you’ve taken an economics course or regularly read the finance section of the Economist, however, you shouldn’t have any trouble following their arguments.

What the book reinforced for me is that lawmakers need to adjust their economic policymaking to reflect these new realities. For example, the tools many countries use to measure intangible assets are behind the times, so they’re getting an incomplete picture of the economy. The U.S. didn’t include software in GDP calculations until 1999. Even today, GDP doesn’t count investment in things like market research, branding, and training—intangible assets that companies are spending huge amounts of money on.

Measurement isn’t the only area where we’re falling behind—there are a number of big questions that lots of countries should be debating right now. Are trademark and patent laws too strict or too generous? Does competition policy need to be updated? How, if at all, should taxation policies change? What is the best way to stimulate an economy in a world where capitalism happens without the capital? We need really smart thinkers and brilliant economists digging into all of these questions. Capitalism Without Capital is the first book I’ve seen that tackles them in depth, and I think it should be required reading for policymakers.

It took time for the investment world to embrace companies built on intangible assets. In the early days of Microsoft, I felt like I was explaining something completely foreign to people. Our business plan involved a different way of looking at assets than investors were used to. They couldn’t imagine what returns we would generate over the long term.

The idea today that anyone would need to be pitched on why software is a legitimate investment seems unimaginable, but a lot has changed since the 1980s. It’s time the way we think about the economy does, too.

Rise? Sure. Fall? Nope.

America’s best days are not behind us

They’re not behind us.

I generally read books that I expect to enjoy. But based on reviews I had seen, I was prepared to be more frustrated than fascinated by Robert Gordon’s new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth. So you can imagine my surprise when I discovered how much I liked it.

Most reviews have focused on the “fall” indicated in the title: the last hundred pages or so, in which Gordon predicts that the future won’t live up to the past in terms of economic growth. I strongly disagree with him on that point, as I discuss below. But I did find his historical analysis, which makes up the bulk of the book, utterly fascinating. (And, at 743 pages, the book has a lot of bulk. Gordon’s two-part piece in Bloomberg View is a helpful summary for anyone who won’t get through the whole thing.)

Gordon paints a vivid picture of the years between 1870 and 1970, a century of unprecedented growth in the United States. This was the century that brought us the great inventions that fundamentally changed our standard of living—inventions like the electrical grid, indoor plumbing, automobiles, and antibiotics.

Gordon does a phenomenal job illustrating just how different life was in 1870 than it was in 1970, through both an economic analysis and engaging narrative descriptions.

Consider that in 1870, most homes were lit by candles and whale oil lamps. To use the bathroom, your choice was an outhouse or a chamber pot. Your world was confined to the distance your horse could travel. You would spend long hours of your short life doing backbreaking labor, owning only two changes of clothes, and eating a whole lot of pork and grain mush.

By 1970, homes—and people—became, to use Gordon’s term, networked. The advent of electricity, cars, indoor plumbing, and telephones meant that people were more connected than ever, dramatically improving quality of life and increasing productivity to previously unseen levels.

What really amazed me was not the speed of innovation but the speed of adoption. In 1910, there were 2.3 motor vehicle registrations for every 100 households. By 1930, there were eighty-nine.

In its impact on the standard of living, the arrival of the automobile was rivaled only by the commercialization of electricity. It’s hard for many of us to imagine living in the dim, smelly, and smoky dwellings of 1870, washing clothes by hand, heating irons on a gas or wood stove, and eating only food that didn’t require refrigeration. By 1970, you could walk into most houses and see a refrigerator, an iron, a washing machine. It would look pretty much the same as any house you’d walk into today, with a couple notable exceptions like the microwave (and color schemes with a lot less harvest gold).

I found Gordon’s historical analysis eye-opening. And that’s why I think the attention that reviewers have paid to his predictions for the future, which make up only two chapters, distracts from the impact of the book.

Gordon argues that American growth can never be what it was between 1870 and 1970 because the fruits of the digital revolution will not live up to the legacy of the great inventions that transformed life in the 19thth and 20 centuries.

I couldn’t disagree more.

Gordon’s premise is that what he calls the third industrial revolution, the one driven by computers and digitalization, is limited to communication, information, and entertainment. I believe it’s far broader than that.

The digital revolution affects the very mechanism of the marketplace. How buyers and sellers find each other, how we amass information, how we can create models to simulate things before building them, how scientists collaborate across continents, how we learn new things—all of this has changed dramatically thanks to digital innovation. Yes, household appliances look pretty much the same now as they did in 1970, but that doesn’t mean our lives in 2070 won’t be profoundly different.

As Gordon acknowledges many times, we don’t have a good tool for measuring the impact of innovation on people’s lives. Like other economists, Gordon uses something called Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which is meant to capture efficiency due to innovation. TFP is based on GDP but takes into account the hours we work and the equipment we use.

The truth is, while economic measurements like TFP can be useful for understanding the impact of a tractor or a refrigerator, they are much less useful for understanding the impact of Wikipedia or Airbnb.

How do you calculate the value of millions of pages of free information at your fingertips? How do you calculate the impact of the entire hospitality industry flipped on its head? In the future, GDP may not grow as fast as it did in the past—or, for all we know, it may—but that alone doesn’t tell you whether people’s lives are going to get better.

Implicit in Gordon’s analysis is that nearly all the big problems have been solved, and any improvements over the coming decades will be at the margins. Gordon’s refrain, referring to automobiles and refrigerators and telephone systems, is “These achievements could happen only once.” This is true—but it’s true for things in the future, too. By Gordon’s definition, a robot that’s better at seeing and manipulating things than humans will only happen once. A cure for Alzheimer’s will only happen once.

And when they do happen, the change in our standard of living will be anything but marginal. Think of a cure for Alzheimer’s. That disease costs the U.S. $236 billion per year, mostly to Medicare and Medicaid. A cure would immediately alter the budget of every state in the country, not to mention millions of lives.

In the final chapter of the book, Gordon mentions “headwinds” that he predicts will further hamper U.S. growth and progress in the coming decades, including inequality, a broken education system, an aging population, and government debt.

I certainly agree that these are big problems. Reducing inequality and making sure every child in the country is ready for college and the workforce has been a major focus of our foundation’s U.S. Program. But America had problems with inequality and education in the past, and they didn’t prevent great inventions from having a big impact. Moreover, I’m optimistic that some of the great inventions of the future will be considered great because of their success at addressing these problems directly.

And I should add that Gordon limits his scope, understandably, to the U.S. But you can’t read his book without thinking about the billions of people around the world for whom a quality of life equal to the America of 1970 would be a vast improvement.

Learning about the speed at which the U.S. was able to spread innovations—from sanitation to electricity—makes me more hopeful about what is possible for the world rather than less hopeful about what is in store for America.

The book was a fantastic read, and well worth the time. When it comes to choosing a side in the debate between optimism and pessimism, my money is on the incredible forces of technological progress at work every day. Although the book is called The Rise and Fall of American Growth, I am confident that “fall” will not be the final word in America’s story.

Phoenix in the East

Can Japan come back?

The Power to Compete has smart ideas about revitalizing the country’s economy.

I have a soft spot for Japan. I have visited it more times than I can count. I’m fascinated by its unique mix of tradition and modernity. And Japan was the site of Microsoft’s first office outside the United States. Kay Nishi, who opened that office, is an amazing thinker, and one of the most under-appreciated leaders in the company’s history. With Kay’s help, there were a few years where Microsoft did more business in Japan than we did in the United States.

Of course Japan is also intensely interesting to anyone who follows global economics. In the 1980s, it was a juggernaut. Countless books and articles touted the effectiveness of Japan’s state-controlled capital and the businesses where employees would sing the company song every morning. There was serious discussion about whether America needed higher tariffs to challenge Japan.

That is not the case today. Many of Japan’s companies have been eclipsed by competitors in South Korea and China. Samsung, based in Seoul, is worth more than all Japanese consumer electronics companies combined. And the economy has experienced deflation—a downturn that many economists once thought was limited to Japan, but now seems to be more global. So what happens in Japan matters a lot to the rest of the world.

How did Japan lose its way? Can it come back?

There is no shortage of books wrestling with these questions. One that I read recently and found super-interesting is The Power to Compete: An Economist and an Entrepreneur on Revitalizing Japan in the Global Economy, by the father-and-son team Ryoichi Mikitani and Hiroshi Mikitani. It is a series of dialogues between Hiroshi—founder of the Internet company Rakuten—and his father, Ryoichi, a respected economist and author. (Ryoichi Mikitani died in 2013.)

A while back I spent a day with Hiroshi and found him to be a bright, engaging guy. I gather that he is viewed as something of a maverick in Japan. In The Power to Compete he lays out a five-point plan for revitalizing Japan’s economy, which includes relaxing regulations on business, encouraging innovation, engaging more globally, and building up the “Made in Japan” brand.

The book is a quick read at just over 200 pages. Although I don’t agree with everything in Hiroshi’s program, I think he has a number of good ideas. He talks about bringing more women into the workforce and encouraging more people to learn and use English. And I would love to see Japanese companies become more innovative—not just because it will make them more competitive, but because the whole world benefits from great ideas and technologies, whoever invents them.

Ultimately, I am bullish on Japan. It is still a wealthy country. It has come back from much worse circumstances, as any student of World War II knows. The quality of life there is high, and its education system is strong (although Ryoichi Mikitani argues that it should spend more on schools). The country is unlikely to emerge as the singular leader it was in the 1980s, but its future is still quite bright.

If you’re as interested in Japan as I am, I think you’ll find that The Power to Compete is a smart and thought-provoking look at the future of a fascinating country.

From Japan to Djibouti

Can the Asian miracle happen in Africa?

Can the lessons from Asia’s rise apply on another continent?

I read Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works because it claimed to answer two of the greatest questions in development economics: How did countries like Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and China achieve sustained, high growth and turn into development success stories? And why have so few other countries managed to do so? Clear answers could benefit billions of people living in countries that are poor today but have the essential ingredients to develop thriving economies.

I’m pleased to report that Studwell, a smart business journalist, delivers clear answers—not the hedged “on the one hand, on the other hand” answers that led an exasperated Harry Truman to ask for a “one-armed economist.” I found the book to be quite compelling. Studwell explains economic history in a concise and understandable way. I asked the whole Agriculture team at our foundation to read it because of its especially good insights into the critical role of household farming for economic development.

So what are Studwell’s answers to the multi-trillion-dollar question of why some Asian countries developed rapidly and others (Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand) did not? He offers a simple, three-part formula:

- Create conditions for small farmers to thrive.

- Use the proceeds from agricultural surpluses to build a manufacturing base that is tooled from the start to produce exports.

- Nurture both these sectors (small farming and export-oriented manufacturing) with financial institutions closely controlled by the government.

Here’s the formula in slightly greater depth:

Agriculture: Studwell’s book does a better job than anything else I’ve read of articulating the key role of agriculture in development. He explains that the one thing that all poor countries have in abundance is farm labor—typically three quarters of their population. Unfortunately, most poor countries have feudal land policies that favor wealthy landowners, with masses of poor farmers working for them. Studwell argues that these policies not only produce huge inequities; they also guarantee lousy crop yields. Conversely, he says, when you give farmers ownership of modest plots and allow them to profit from the fruits of their labor, farm yields are much higher per hectare. And rising yields help countries generate the surpluses and savings they need to power up their manufacturing engine.

Manufacturing: Studwell argues that once countries are producing steady agricultural surpluses, they should start moving to the manufacturing phase of development. He makes a strong historical case that the successful countries do not simply rely on the invisible hand of market forces; they supplement market forces with the heavy hand of state-driven industrial policy. These countries engage in a combination of protectionism (coddling infant industries to give them time to become globally competitive) and then culling losers (cutting off resources to firms that don’t succeed in export markets).

Finances: Studwell shows that rapidly developing countries usually give lip service to free-market principles while actually keeping their financial institutions “on a short leash.” In other words, they enact policies to protect themselves against the shocks and whiplash of global-capital flows, and they make sure their financial institutions serve the country’s long-term development ends rather than the short-term interests of financiers.

I came away from the book with many take-home messages that apply to our foundation’s work. I’ll highlight two.

First, I appreciated Studwell’s thinking about agriculture economics. Drawing on data on crop yields and overall agricultural output, he argues that rapid agricultural development requires redistributing land more equitably among the farming population. To date, I haven’t focused as much on the land ownership piece as I have on the role of better seeds, fertilizers, and farming practices. This book made me to want to learn more about the land ownership picture in countries where our foundation funds work.

Second, Studwell provoked me to think hard about whether his three-part formula is as applicable to Africa as it is to Asia. Certainly, the agricultural piece applies well—and has many economic and health benefits. The big question for me is: Can African countries become successful export-oriented manufacturing hubs? I do see this potential in countries like Ethiopia and Djibouti. They already have a strong connection with China and ambitious, long-term economic plans. Unfortunately, many other countries on the continent don’t have those same success factors, especially landlocked ones with very poor infrastructure. Helping farmers in those countries grow more food and earn more money would be a big help on its own.

How Asia Works is not a gripping page-turner aimed at general audiences, but it’s a good read for anyone who wants to understand what actually determines whether a developing economy will succeed. Studwell’s formula is refreshingly clear—even if it’s very difficult to execute.

Wealth and Capital

Why inequality matters

My thoughts on Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

A 700-page treatise on economics translated from French is not exactly a light summer read—even for someone with an admittedly high geek quotient. But this past July, I felt compelled to read Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century after reading several reviews and hearing about it from friends.

I’m glad I did. I encourage you to read it too, or at least a good summary, like this one from The Economist. Piketty was nice enough to talk with me about his work on a Skype call last month. As I told him, I agree with his most important conclusions, and I hope his work will draw more smart people into the study of wealth and income inequality—because the more we understand about the causes and cures, the better. I also said I have concerns about some elements of his analysis, which I’ll share below.

I very much agree with Piketty that:

- High levels of inequality are a problem—messing up economic incentives, tilting democracies in favor of powerful interests, and undercutting the ideal that all people are created equal.

- Capitalism does not self-correct toward greater equality—that is, excess wealth concentration can have a snowball effect if left unchecked.

- Governments can play a constructive role in offsetting the snowballing tendencies if and when they choose to do so.

To be clear, when I say that high levels of inequality are a problem, I don’t want to imply that the world is getting worse. In fact, thanks to the rise of the middle class in countries like China, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, and Thailand, the world as a whole is actually becoming more egalitarian, and that positive global trend is likely to continue.

But extreme inequality should not be ignored—or worse, celebrated as a sign that we have a high-performing economy and healthy society. Yes, some level of inequality is built in to capitalism. As Piketty argues, it is inherent to the system. The question is, what level of inequality is acceptable? And when does inequality start doing more harm than good? That’s something we should have a public discussion about, and it’s great that Piketty helped advance that discussion in such a serious way.

However, Piketty’s book has some important flaws that I hope he and other economists will address in the coming years.

For all of Piketty’s data on historical trends, he does not give a full picture of how wealth is created and how it decays. At the core of his book is a simple equation: r > g, where r stands for the average rate of return on capital and g stands for the rate of growth of the economy. The idea is that when the returns on capital outpace the returns on labor, over time the wealth gap will widen between people who have a lot of capital and those who rely on their labor. The equation is so central to Piketty’s arguments that he says it represents “the fundamental force for divergence” and “sums up the overall logic of my conclusions.”

Other economists have assembled large historical datasets and cast doubt on the value of r > gr > g for understanding whether inequality will widen or narrow. I’m not an expert on that question. What I do know is that Piketty’s doesn’t adequately differentiate among different kinds of capital with different social utility.

Imagine three types of wealthy people. One guy is putting his capital into building his business. Then there’s a woman who’s giving most of her wealth to charity. A third person is mostly consuming, spending a lot of money on things like a yacht and plane. While it’s true that the wealth of all three people is contributing to inequality, I would argue that the first two are delivering more value to society than the third. I wish Piketty had made this distinction, because it has important policy implications, which I’ll get to below.

More important, I believe Piketty’s r > g analysis doesn’t account for powerful forces that counteract the accumulation of wealth from one generation to the next. I fully agree that we don’t want to live in an aristocratic society in which already-wealthy families get richer simply by sitting on their laurels and collecting what Piketty calls “rentier income”—that is, the returns people earn when they let others use their money, land, or other property. But I don’t think America is anything close to that.

Take a look at the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans. About half the people on the list are entrepreneurs whose companies did very well (thanks to hard work as well as a lot of luck). Contrary to Piketty’s rentier hypothesis, I don’t see anyone on the list whose ancestors bought a great parcel of land in 1780 and have been accumulating family wealth by collecting rents ever since. In America, that old money is long gone—through instability, inflation, taxes, philanthropy, and spending.

You can see one wealth-decaying dynamic in the history of successful industries. In the early part of the 20th century, Henry Ford and a small number of other entrepreneurs did very well in the automobile industry. They owned a huge amount of the stock of car companies that achieved a scale advantage and massive profitability. These successful entrepreneurs were the outliers. Far more people—including many rentiers who invested their family wealth in the auto industry—saw their investments go bust in the period from 1910 to 1940, when the American auto industry shrank from 224 manufacturers down to 21. So instead of a transfer of wealth toward rentiers and other passive investors, you often get the opposite. I have seen the same phenomenon at work in technology and other fields.

Piketty is right that there are forces that can lead to snowballing wealth (including the fact that the children of wealthy people often get access to networks that can help them land internships, jobs, etc.). However, there are also forces that contribute to the decay of wealth, and Capital doesn’t give enough weight to them.

I am also disappointed that Piketty focused heavily on data on wealth and income while neglecting consumption altogether. Consumption data represent the goods and services that people buy—including food, clothing, housing, education, and health—and can add a lot of depth to our understanding of how people actually live. Particularly in rich societies, the income lens really doesn’t give you the sense of what needs to be fixed.

There are many reasons why income data, in particular, can be misleading. For example, a medical student with no income and lots of student loans would look in the official statistics like she’s in a dire situation but may well have a very high income in the future. Or a more extreme example: Some very wealthy people who are not actively working show up below the poverty line in years when they don’t sell any stock or receive other forms of income.

It’s not that we should ignore the wealth and income data. But consumption data may be even more important for understanding human welfare. At a minimum, it shows a different—and generally rosier—picture from the one that Piketty paints. Ideally, I’d like to see studies that draw from wealth, income, and consumption data together.

Even if we don’t have a perfect picture today, we certainly know enough about the challenges that we can take action.

Piketty’s favorite solution is a progressive annual tax on capital, rather than income. He argues that this kind of tax “will make it possible to avoid an endless inegalitarian spiral while preserving competition and incentives for new instances of primitive accumulation.”

I agree that taxation should shift away from taxing labor. It doesn’t make any sense that labor in the United States is taxed so heavily relative to capital. It will make even less sense in the coming years, as robots and other forms of automation come to perform more and more of the skills that human laborers do today.

But rather than move to a progressive tax on capital, as Piketty would like, I think we’d be best off with a progressive tax on consumption. Think about the three wealthy people I described earlier: One investing in companies, one in philanthropy, and one in a lavish lifestyle. There’s nothing wrong with the last guy, but I think he should pay more taxes than the others. As Piketty pointed out when we spoke, it's hard to measure consumption (for example, should political donations count?). But then, almost every tax system—including a wealth tax—has similar challenges.

Like Piketty, I’m also a big believer in the estate tax. Letting inheritors consume or allocate capital disproportionately simply based on the lottery of birth is not a smart or fair way to allocate resources. As Warren Buffett likes to say, that’s like “choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the gold-medal winners in the 2000 Olympics.” I believe we should maintain the estate tax and invest the proceeds in education and research—the best way to strengthen our country for the future.

Philanthropy also can be an important part of the solution set. It’s too bad that Piketty devotes so little space to it. A century and a quarter ago, Andrew Carnegie was a lonely voice encouraging his wealthy peers to give back substantial portions of their wealth. Today, a growing number of very wealthy people are pledging to do just that. Philanthropy done well not only produces direct benefits for society, it also reduces dynastic wealth. Melinda and I are strong believers that dynastic wealth is bad for both society and the children involved. We want our children to make their own way in the world. They’ll have all sorts of advantages, but it will be up to them to create their lives and careers.

The debate over wealth and inequality has generated a lot of partisan heat. I don’t have a magic solution for that. But I do know that, even with its flaws, Piketty’s work contributes at least as much light as heat. And now I’m eager to see research that brings more light to this important topic.

Treasury Trove

A front row view of the financial crisis

Timothy Geithner’s account of fighting a global meltdown.

The central irony of Stress Test, the new memoir by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, is that a guy who was accused of being a lousy communicator while in office has penned a book that is such a good read.

I’m not qualified to weigh in on the accuracy of Geithner’s recollections, some of which have been called into question by those Geithner criticizes. And of course Geithner provides only one perspective; the verdict may evolve as we learn more from other participants in the crisis. But I’ve now read four or five of these first drafts of the history of the Great Recession, and I believe Stress Test represents the biggest contribution of the bunch.

While some chapters dive into details that only a true policy wonk could love, I found the entire book very clear and easy to read. Geithner could more than hold his own in an explanatory-metaphor contest with masters like Warren Buffett and the author Michael Lewis. For example:

“Even if we couldn’t prevent an ugly crash, I wanted to explore ways to put ‘foam on the runway.’ ” Or: “When I saw The Hurt Locker, the Oscar-winning film about a bomb disposal unit in Iraq … I knew I had finally found something that captured what the crisis felt like: the overwhelming burden of responsibility combined with the paralyzing risk of catastrophic failure; the frustration about the stuff out of your control; the uncertainty about what would help; the knowledge that even good decisions might turn out badly….”

Ultimately, Geithner paints a compelling human portrait of what it was like to be fighting a global financial meltdown while at the same time fighting critics inside and outside the Administration—as well as his own severe guilt over his near-total absence from his family.

When I ran Microsoft, I sometimes thought I had a tough job, especially when trying to manage the company and deal with a federal anti-trust trial at the same time. But I came away from this book thinking my job was pretty easy compared with what Geithner signed up for. Unless you’re a soldier on active combat duty, you’re likely to think the same thing.

I can understand why Geithner, who acknowledges how hard it is for him to sit still, felt compelled to take the time to write his own 550-page version of events. Given that he’s still taking intense criticism, he had to be saying to himself, “Cut me some slack here!”

For all of Geithner’s actual or perceived mistakes and the horrible optics of bailouts and bonuses, he and his colleagues at Treasury and the Federal Reserve deserve credit for keeping the world economy from going over the cliff. We easily could have had a devastating depression with breadlines and shantytowns all over the country and, indeed, the world. Not only did Geithner and his colleagues prevent the worst from happening; the financial bailout has now turned a tidy profit for U.S. taxpayers. Bailing out the “too big to fail” banks as well as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG, GM, Chrysler, and all the others netted a surplus of $166 billion. As Geithner accurately puts it, “The financial industry paid for the rescue.”

Yet those facts don’t seem to count for much. Geithner continues to be pilloried by people who seem to have mutually exclusive critiques. He’s viewed by critics on the left as a soulless tool who cared more about bankers than the victims of their greed. Critics on the right seem to believe he’s a raging socialist hell bent on destroying American capitalism.

Logically speaking, both can’t be true. And I can tell you, based on my four or five meetings with him over the years, that neither is. In my view, he’s a smart, humble, non-ideological guy who, contrary to popular belief, had never worked for Wall Street prior to the crash. Perhaps history will determine that he could have done more to bring down unemployment and help more struggling families stay in their homes. But I’m certain he genuinely cares about doing the right thing for Main Street.

While Geithner’s frustration is palpable in the book, he indulges in less credit-taking and score-settling than you find in most Beltway memoirs. And he does a decent job of acknowledging his own shortcomings. Here are some examples: “I wish I had pushed harder to improve the financial system’s ability to withstand a crisis of confidence when I was at the New York Fed.” “Our constant zigzags looked ridiculous.” “It was my own screw-ups that made the inquisition [over errors on his tax returns] possible, and I felt sick that I had put the President-elect in this position.” He is especially unvarnished in his self-criticism of his deficiencies as a communicator (e.g., “My speech … sucked.”)

But he’s unapologetic about the cornerstone of his approach to fighting the crisis. “We provided extraordinary support to the financial system in general and some very poorly managed financial firms in particular,” he writes. “We didn’t do it to help their executives buy fancier mansions and sleeker jets. We did it because there was no other way to prevent a financial calamity from crushing the broader economy.” This explanation passes my sniff test.

During a time of high anxiety and chaos, it’s no wonder that explanations from a lifelong technocrat who has always shied away from public speaking would be no match for the professional loud talkers on radio and cable TV. The reality is, as Bill Clinton once said, “When people feel uncertain, [they’d rather listen to] somebody who’s strong and wrong than somebody who’s weak and right.”

Will this and the other accounts that are sure to come out help policymakers defuse future financial crises?

I hope so. Good books can encourage decision-makers to stop and reflect on brink-of-the-abyss events, weigh the financial and political risks a little differently, and act a bit more proactively when the dark clouds appear once again. All policymakers know there’s a risk that excessive vigilance could gum up markets and slow economic growth. But I think books like this help them see that the risks and pain of being blindsided—left in “shocked disbelief,” as former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan put it—are a real concern too.

To be sure, the politics of fighting financial crises will always be ugly. In Geithner’s words, “Actions that seem reasonable—letting banks fail, forcing their creditors to absorb losses, balancing government budgets…—only make the crisis worse. And the actions necessary to ease the crisis seem inexplicable and unfair.” But it helps if the public knows a little more about the subject—what’s at stake, what the options are, what has worked in similar situations—so that the loud talkers resonate a bit less and the knowledgeable ones a bit more. If Stress Test continues to attract lay readers—and its position on the New York Times bestseller list suggest it could—I think that can make at least a modest difference the next time around.

6/7 of a Good Read

The Great Escape is an excellent book with one big flaw

The Great Escape is an excellent book with one big flaw.

The other day I spoke at an employee event at the Gates Foundation. We do these “unplugged” sessions periodically. I open with a few remarks and then spend an hour or so taking questions from the team. I see our senior staff quite often, but these sessions are a great way to connect with the larger group.

I told the staff: If you want to learn about why human welfare overall has gone up so much over time, you should read The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton, a distinguished Princeton economist who has spent decades studying measures of global poverty. It’s quite accessible, and the first six chapters teach you a lot about economics. But the seventh and final chapter takes a strange turn: Deaton launches a sudden attack on foreign aid. It’s by far the weakest part of the book; if this is the only thing you read about aid, you will come away very confused about what aid does for people.

Deaton’s parting shots came as a surprise to me, because it’s clear from the rest of the book that we see the world in similar ways. His first paragraph is dead-on: “Life is better now than at almost any time in history. More people are richer and fewer people live in dire poverty. Lives are longer and parents no longer routinely watch a quarter of their children die.” (I would have cut “almost” from the first sentence, but otherwise I could not agree more.) Picking up on the title of the old Steve McQueen movie, he calls this improvement in human welfare the Great Escape.

I have long believed that innovation is a key to improving human lives. Advances in biology lead to lifesaving vaccines and drugs. Discoveries in computer science lead to new software and hardware that connect people in powerful new ways. Deaton does a good job of documenting how innovations helped spark the Great Escape.

But the Great Escape, Deaton says, “is far from complete.” Innovations reach only those who can afford to pay for them. And that has led to great inequality. The rest of the book examines where this inequality comes from, whether it matters, and what if anything can be done about it.

One of Deaton’s most helpful passages explains how you measure human welfare in the first place. He argues that there’s no single good measure, but health and GDP are the best two that we have. You probably have heard about gross domestic product, or GDP, but you might not know how it’s calculated, how it’s different from gross national product, or why on its own GDP is not a great measure of the quality of people’s lives. Deaton provides a lucid and succinct explanation.

He is also humble about the limits of economic analysis. In this entertaining passage, he goes after economists who make unfounded assertions about economic growth:

Economists, international organizations, and other commentators are fond of taking a few high-growth countries and looking for some common feature or policy, which is then held up as the “key to growth”—at least until it fails to open the door to growth somewhere else. The same goes for attempts to look at countries that have done badly (the “bottom billion”) and divine the causes of their failure. These attempts are much like trying to figure out the common characteristics of people who bet on the zero just before it came up on a roulette wheel; they do little but disguise our fundamental ignorance.

Unfortunately, this humility goes out the window once Deaton starts criticizing foreign aid. After examining the history of GDP in countries that get aid, he concludes that aid doesn’t cause growth. In fact he makes an even stronger claim—that aid keeps poor countries from growing—and says the most compassionate thing we can do is to stop giving it.

In other words, in one chapter, Deaton dismisses people who think they know why countries fail to grow. In the next, he asserts that countries fail to grow because of aid.

Deaton makes another common mistake among aid critics: He talks about foreign aid as if it’s one homogeneous lump. He judges money for buying vaccines by the same standard as money for buying military hardware.

It seems obvious that programs should be measured against their original purpose. Did the program have a good goal, and did it achieve the goal? Instead, Deaton and other aid critics look at, say, aid that was designed to prop up some American industry, see that it didn’t raise GDP in poor countries, and conclude that aid must be a failure.

That’s a shame, because programs that are actually designed to improve human welfare—especially health and agriculture—are some of the best spending that a rich country can do on behalf of the poor. They help the poor benefit from the very innovations Deaton writes about so glowingly. And their success rate is at least as good as the track record of venture capital firms. No one looks around Silicon Valley and says, “Look at all the startups that go under! Venture capital is such a waste. Let’s shut it down.” Why would you say that about aid?

Deaton spends a lot of time on the concern that foreign aid undermines the connection between governments and their people. The idea is that leaders of countries that get a lot of aid will worry more about what their donors think than what their citizens think.

This argument always strikes me as strange. For one thing, many countries—Botswana, Morocco, Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, Peru, Thailand, Mauritius, Singapore, and Malaysia, to name a few—have grown so much that they receive hardly any aid today. Deaton doesn’t cite any evidence that aid undermined their institutions or democratic values. And his over-emphasis on institutions leads him to make sweeping statements like “drugs and vaccines save lives, but the pernicious effects are always there.” I have to wonder what pernicious effects came from eradicating smallpox, and whether these effects could be worse than a disease that killed millions of people every year for centuries.

Deaton is right to point out some problems with aid. For example, too much goes to upper-middle-income countries rather than focusing on the poorest people. More aid can be directed to specific goals like vaccination. And aid shouldn’t be used to replace domestic funding. But I wish he had spent more time than he does exploring better ways to give aid. Most importantly, we need to help develop a system that identifies the goals of every type of aid and makes it easier to measure which approaches work best in various situations.

If you read The Great Escape—and there’s a lot to recommend in it—you should also read something else to balance out Deaton’s negative views on aid. I’ve highlighted a few recommendations in the Other Reviews box at the bottom of this page. They’ll give you a clearer sense of what’s working, what isn’t, and how we can make our efforts even more effective in the years ahead.

Out of the Box

Innovation, disruption, and progress: what do vaccines, software, and shipping containers have in common?

Shipping containers are way more interesting than you might think.

In the second half of the twentieth century, an innovation came along that would transform the way the world did business. At first, some people wrote it off as a fad. Others kept at it, convinced that it was going to have a huge impact. Some of the companies that made big bets on this tool were very successful, while others ended up going under. Ultimately, it helped accelerate the globalization that had already been under way for centuries.

I’m not talking about software. I’m talking about the shipping industry, and in particular an innovation you might not have thought much about: the shipping container. It is the subject of an excellent book I read this summer called The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, by a former Economist editor named Marc Levinson. The Box is mostly about globalization, but there is also a larger story here that touches on business and philanthropy more broadly.

For centuries, cargo ships were loaded and unloaded by hand, one crate at a time. Each crate might have a different destination, which made the whole process slow and expensive. In 1956, a trucking magnate named Malcolm McLean had a clever idea: Instead of unloading a trailer’s worth of crates onto a ship, why not put the whole trailer on the ship?

It was the beginning of a revolution in the way goods move around the world. Shipping lines ordered bigger and bigger ships to accommodate the aluminum boxes that soon became the standard container. Port cities from New York to Singapore raced to modernize their facilities to accommodate the larger ships.

By the early 1980s, the transition to the containerized system was essentially complete. Computers were coming into the picture as well. I remember meeting with the leaders of port authorities that wanted to go paperless. They would ask, Are the computer systems reliable? How do they work? Today it seems crazy that a ship would dock and somebody would get off with a piece of paper to show what’s in the cargo hold.

The move to containerized shipping had an amazing impact on the global economy. As Levinson says, “A machine manufactured on Monday can be dropped at Port Newark on Tuesday and delivered in Stuttgart, Germany, in less time than it once would have taken to be loaded aboard a ship.” He cites one study that says the container system reduced freight rates from Asia to North America by 40 to 60 percent. At the same time, it also led to job losses at ports, since greater efficiency meant you could move more freight with fewer dock workers.

The story of this transition is fascinating and reason enough to read the book. But in subtle ways The Box also challenges commonly held views about business and the role of innovation.

For example, you often hear that it’s a big advantage to get into a particular business early. But in both software and shipping, that wasn’t necessarily the case. Some shipping companies made big bets early, and still failed. Apple was an early entrant in the PC business but didn’t take off until many years later. At Microsoft it certainly helped that we got an early start, but we never took that advantage for granted.

Or consider the conditions that make it possible for an innovation to take hold. You often hear simplistic arguments that it never happens without government involvement, or the opposite, that government only gets in the way. But the truth is more complicated. For example, there was no way that shipping companies in the 1950s and 1960s could raise enough capital to invest in new cranes, deepening waterways, and other changes that ports needed to take advantage of the new containers and ships. Only governments could do that. On the other hand, Levinson makes it clear that governments’ overregulation of the transportation sector held back a lot of innovation and kept costs high. So it is a complex picture.

That’s also true when it comes to setting standards. The container revolution only took off after all the boxes were built in compatible shapes and sizes, which meant they could be transported on ships, trucks, and trains from different companies. Similarly, the Internet relies on a common protocol for sending information. But it’s very hard to know ahead of time where these standards will come from. Few people would have predicted that the Internet protocol would grow out of a university research project funded by the U.S. Department of Defense. In the case of shipping containers, it took several years and the efforts of an obscure government agency and several industry groups to come to agreement.

These questions also touch on a lot of the work Melinda and I are doing through the Gates Foundation. For example, how can advances in shipping help deliver vaccines to remote areas, while keeping them cold so they don’t spoil? In education, many states are adopting common academic standards; how can these standards encourage software companies to develop new tools for teachers and students across the country?

Few people in the 1950s understood just how important the shipping container would be in shaping the global economy. That’s often the case with innovation—it’s hard to predict which ones will fizzle and which ones will change the world. That’s why it’s so important to keep investing in a broad range of innovations, whether they’re in the field of genetics, robotics, agriculture, or other areas. It’s the key to saving lives, driving human progress, and making the world a fairer place. You never know where the next shipping container will come from.

GDP Measurements

If we can get the numbers right, we can help more people

Jerven provides an analysis of African economic development statistics.

Even in the best financial times, budgets for development aid are hardly overflowing. Government leaders and donors have to make hard decisions about where to focus their limited resources. How do you decide which countries should get low-cost loans or cheaper vaccines, and which can afford to fund their own development programs?

Traditionally, one of the guiding factors has been per-capita Gross Domestic Product – the value of goods and services produced by a country in a year divided by the country’s population.

Yet there are problems with GDP as a statistic. It may be very inaccurate in the poorest countries. These problems are not just a concern for policymakers or hardcore people like me who read lots of World Bank reports. They are relevant for anyone who wants to use statistics to make the case for helping the world’s poorest people. The question of how we measure growth and improvements in people’s lives—and how we know what works—is very important.

I’ve long believed that GDP understates growth even in rich countries, where its measurement is quite sophisticated. This is because it’s so difficult to compare the value of baskets of goods across different time periods. In the U.S. for example, a set of encyclopedias in 1960 was expensive but held great value for families with studious kids. (I can speak from experience, having spent many hours with the World Book encyclopedias my parents bought for my sisters and me.) Now, thanks to the Internet, kids have access to far more information for free. How do you factor that into GDP? It’s very difficult.

The challenges with calculating GDP are particularly acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where weak national statistics offices and historical biases muddy the clarity of crucial measurements. Bothered by what he saw as problems in Zambia’s national statistics, Morten Jerven, an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University, spent four years digging into how African nations get their statistics and the challenges they face in turning them into GDP estimates. He details his findings in a new book, Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled By African Development Statistics and What To Do About It, which makes a strong case that a lot of GDP measurements we thought were accurate are far from it.

Jerven notes that many countries in the region have trouble measuring the size of their relatively large subsistence economies and unrecorded economic activity. How do you account for the production of a farmer who grows and eats his own food? If subsistence farming is systematically underestimated, then as an economy moves out of subsistence, some of the apparent growth may be just a shift to something that is easier to capture with statistics.

There are other problems with GDP statistics for poor countries. For example, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa don’t update their reporting often enough, so their GDP numbers may miss large and fast-growing sectors of the economy, like cell phones. A few years ago, Ghana updated its reporting and its GDP jumped by 60 percent. But many people didn’t understand this was just a statistical anomaly, rather than an actual change in the standard of living there.

In addition, there are several ways to calculate GDP, and they can produce wildly different results. Jerven mentions three in particular: the World Development Indicators, which are published by the World Bank and by far the most commonly used dataset; the Penn World Table, released by the University of Pennsylvania; and the Maddison tables, published by the University of Groningen and based on work by the late economist Angus Maddison.

These groups use the same basic data as input, but they modify it in different ways to account for inflation and other factors. As a result, their rankings of different countries’ economies can vary widely. Liberia’s GDP ranks it as either 2nd poorest, 7th poorest, or 22nd poorest in Sub-Saharan Africa, depending on which source you consult. I have reproduced one of Jerven’s tables to show you three of the most striking examples.

Which countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are growing and which aren’t? Traditionally, economists have used GDP to help answer that question. But GDP is a problematic number, especially for the poorest countries. Different sources of GDP data produce radically different rankings. Fortunately, we have better ways to measure a country’s well-being, as well as the impact of aid programs. That helps ensure that aid is effective and reaches the people who need it most.

It’s not just the relative rankings that differ. Sometimes one source will show a country growing several percentage points, and another source will show it shrinking over the same time period.

Jerven uses all these discrepancies to argue that we can’t be certain whether one poor country’s GDP is higher than another’s, and that we shouldn’t use GDP alone to make judgments about which economic policies lead to growth.

Does that mean that we don’t know anything about what works in development and what doesn’t?

Not at all. For years, researchers have used techniques like periodic household surveys to collect data. In health, a survey called the Demographic and Health Survey is done regularly to determine things like childhood and maternal death rates. Although they aren’t perfect, these methods aren’t susceptible to the same problems as GDP. Economists are also using new techniques like satellite mapping of light sources to inform their estimates of economic growth.

There are other ways to measure overall living standards in a country. While they aren’t perfect either, they do give us additional ways to understand poverty. One called the Human Development Index uses health and education statistics in addition to GDP. Another, the Multidimensional Poverty Index, uses ten indicators, including nutrition, sanitation, and access to cooking fuel and water. A measure called Purchasing Power Parity looks at how much it would cost to buy the same basket of goods and services in different countries, which helps economists adjust GDP to get better insight into living standards.

Yet it is clear to me that we need to put greater resources into getting basic GDP numbers right. As Jerven argues, national statistics offices across Africa need more support so they can obtain and report more timely and accurate data. Donor governments and international organizations such as the World Bank need to do more to help African nations produce a clearer picture of their economies. And African policymakers need to be more consistent about demanding better statistics and using them to inform decisions.

I’m a big advocate for investing in health and development around the world. The better tools we have for measuring progress, the more we can ensure those investments are reaching the people who need them the most.

Assessing Development Aid

Small adjustments to aid programs can yield big results

A great source of data-driven wisdom about development aid.

As I prepare for the G20 summit, I firmly believe that data has to be at the core of the analysis and conclusions in our report on development. At the same time, we need to look beyond the numbers and understand the everyday challenges faced by the world’s poorest people. The book Poor Economics is very helpful, because it is both empirically rigorous and insightful about the realities that the data doesn’t always capture.

Poor Economics is by two MIT economists, Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee and Esther Duflo. Their life’s work is traveling to poor countries, looking closely at what works and what doesn’t work in efforts to fight hunger and disease, improve education, and broaden access to basic financial services. The authors are directors of J-PAL, an MIT poverty action lab that’s a network of 59 professors around the world who use scientific methods to answer critical questions about alleviating poverty.

To me, what’s really great about J-PAL is that it’s producing scientific evidence that can help make our anti-poverty efforts more effective. This is tremendously important. The money that governments invest in development is saving millions of lives, and improving hundreds of millions. But to sustain support for these efforts, we need to rigorously assess the cost-effectiveness and overall impact of aid, and make continuous improvements.

J-PAL conducts randomized evaluations of different approaches to achieving a particular objective, such as reducing malnutrition. For example, researchers try different ways of distributing food aid in similar villages, observe what happens, and compare the results. They’ve repeatedly found that outside of situations where there’s actual famine, just handing out food – no matter how nutritious – doesn’t necessarily improve nutrition. Sometimes people just cut back on their own food purchases and use that money for something else they need or want, even though consuming more calories could increase their productivity.

Although this may seem strange to us, J-PAL probes deeper to find out why people do what they do. In some instances, they may be in a situation where consuming more calories to work harder will not raise their incomes much or at all. And they may have other, urgent expenses, such as for health care.

Poor Economics does a great job of bringing alive the complexities of poor people’s lives. It explores the tough, difficult decisions they must make – often based on very little information and with no room for error – about things that most of us take for granted, like access to enough food, clean water or vaccinations.

Poor Economics focuses on the specific results and unintended consequences of anti-poverty projects, and in doing so, it reveals some smart strategies for achieving positive results. In some situations, for instance, limited aid may go farther if it is directed toward specific groups of people. One example mentioned in the book is delivering food aid and nutrition information to pregnant women and to children whose development can be permanently stunted by malnutrition.

Related to food aid, one of the “win-win” strategies we’re using at the foundation is helping poor farmers sell their produce to aid programs in their own and neighboring countries. That way, the aid programs can fight hunger and help raise the incomes of local farmers at the same time.

Poor Economics also is very good in spotlighting how small tweaks can sometimes turn failing interventions into effective ones. As I’ve learned, this often involves identifying and removing unintended barriers that prevent people from getting vaccinated, say, or using bed nets to prevent malaria. Given the challenges that poor people face in their daily lives, we need to make it as easy as possible for them to get the help they need.

For example, Rajasthan, India, had for a long time suffered from very low immunization rates – about 6%. This despite the government’s providing the vaccines for free. Increasing the vaccination rate was a challenge – walking to the clinics can be a hassle, and the clinics are unpredictably closed. To address these barriers, mobile clinics were established to provide vaccines on site. The impact of these mobile clinics was profound, with full vaccination rates jumping from 6% to more than 18%. Building on this success, the program was further enhanced with an incentive: a bag of lentils to all families vaccinated, which effectively doubled the rate again to 38%. Even with the incentive, the program was twice as cost effective per patient as just the mobile clinics alone, since the clinic staff was much busier. More importantly, a much larger group of children was vaccinated against polio, measles, DPT and tuberculosis – saving families from potential tragedy down the road and government from higher costs of sick care. You can read the J-PAL policy briefcase “Incentives for Immunization” to learn more about this study.

To be more effective, we also need a deeper understanding of people’s values and cultures. I’ve seen first-hand that local knowledge is critical. A couple of years ago, I visited AIDS-prevention projects that our foundation has supported in South Africa. They were effectively reducing AIDS transmission from women to men by persuading adult and teenaged men to be circumcised. As you can imagine, this was not an easy task, but with knowledge and respect, it can be done, and it can save many lives.

With the authors’ experience on the ground and their willingness to go where the evidence leads, I found Poor Economics a refreshing change from the sometimes theoretical and divisive debates that surround development aid. (An excellent companion book I’d also recommend is Getting Better: Why Global Development is Succeeding.)