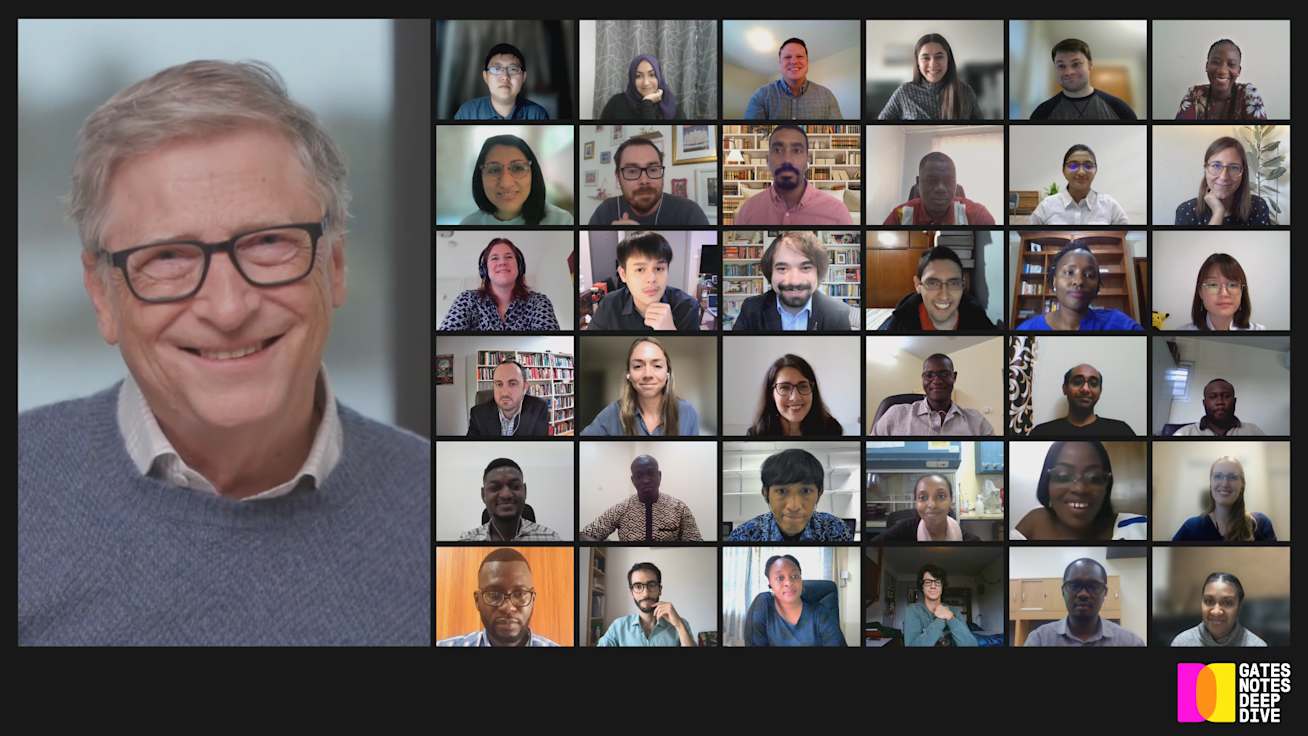

Next generation

These 36 young scientists inspired me

Notes from my recent deep dive on malaria with graduate students.

I recently had an opportunity to meet 36 remarkable graduate students who are focusing their work on malaria. It was the second in a series of conversations we call the Gates Notes Deep Dive—you can read about the first one in this post—and I want to share why I was so inspired by them.

The grad students came from every part of the globe, including Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, South Africa, the United States, Papua New Guinea, India, the United Kingdom, China, Brazil, Australia, and Peru. They covered disciplines ranging from molecular biology and bioinformatics to epidemiology and disease modeling.

It’s amazing to see how much the malaria field has grown in the past two decades. We still need to draw many more people into it, but there’s just no way we could have convened a conversation with so many top students in so many hard-hit countries when I first started working on malaria fifteen years ago.

Before we met, the students heard from four experts doing exciting work on malaria. Epidemiologist Corine Karema spoke about why it’s so hard to eradicate this disease and how we can speed up progress toward eradicating it. Molecular geneticist Ifeyinwa Aniebo discussed the importance of genetic surveillance and the innovations she’s working to introduce in her native Nigeria. Infectious-disease researcher Fredros Okumu addressed the need for new tools that will transform the world’s malaria efforts. And leadership expert Sankara Gitau explored malaria’s impact on women and adolescent girls and the opportunity to advance equality by fighting the disease.

Then I got to meet the students. It was exciting to hear their great questions and feel inspired by their energy. I was fascinated by what they’re worried about and what they’re optimistic about.

For example, we talked a lot about the funding, tools, strategies, and data needed for driving to eradication as fast as we can. I acknowledged that COVID-19 was a gigantic setback for all work in global health. It sapped the financial resources of wealthy countries, forcing them to think about health needs in their own countries. It also interrupted the supply of commodities we need for fighting malaria and other diseases.

I then shared my perspective on how we can make the most of this awful situation. The pandemic has greatly accelerated the science of mRNA vaccines, which is highly relevant for our work to develop more-effective and longer-lasting malaria vaccines. Thirty years of research and development on a pediatric malaria vaccine are paving the way for these improved tools. The one recently approved by the WHO, which our foundation helped fund, is a first-generation product and will need to be used in combination with other interventions. But it’s a major step forward in our goal of developing a highly effective, all-ages elimination vaccine.

I shared with the grad students that the biggest COVID-related opportunity is persuading donors to invest in the R&D, disease monitoring systems, and training we need to be much better prepared for the onset of a future pandemic. People who are working on pandemic prevention can keep their skills sharp by also working on ongoing infectious disease challenges, like polio and malaria. That’s a win-win: It will bring malaria to an end sooner, and it will make sure that the world has a core of experts who are ready to nip any potential pandemic in the bud.

The grad students also engaged me in an interesting conversation about newer technologies that are being applied to the malaria fight. One of these is “gene drive,” a very sophisticated and powerful way to control mosquito populations which was made possible by recent advances in gene editing. And we discussed how the pandemic has made far more people aware of the need to expand the world’s vaccine-manufacturing capacity—so we’ll be able to produce effective and newer vaccines rapidly, in volumes that can meet the global need.

One area of legitimate concern raised was the parasite’s growing resistance to artemisinin, the best anti-malarial drug we currently have. Drug resistance showed up first in Asia. Now we’re seeing signs of resistance in parts of Africa. Some of the foundation’s grantees are developing very promising new medicines that we can eventually combine with artemisinin, but that drug pipeline is about three years behind where I wish it were. I do believe the alternate drugs will come in time, but it’s going to be a closer call than we had hoped.

I’m grateful to the grad students I met—as well as thousands of others around the world who are dedicating their careers to this hard but critically important challenge. Defeating this parasite will take a heroic effort. But the intelligence and passion I saw in those students made me more optimistic than ever that we can do it.