Surrender

The best memoir by a rock star I actually know

I’m lucky to call Bono a friend. But his autobiography still surprised me.

When Paul Hewson was 11, his parents sent him to a Dublin grammar school that happened to have an outstanding boys’ choir. Paul, who later took the nickname Bono, loved singing. His father had a beautiful voice, and Paul thought he might have some of his dad’s talent. But when the principal asked him if he wanted to join the choir, his mom jumped in before he could answer. “Not at all,” she said. “Paul has no interest in singing.”

Bono’s new book, Surrender, is packed with funny, poignant moments like this. Even though I’m a big fan of U2, and Bono and I have become friends over the years—Paul Allen connected us in the early 2000s—a lot of those stories were new to me. I went into this book knowing almost nothing about his anger at his father, the band’s near-breakups, and his discovery that his cousin was actually his half-brother. I didn’t even know that he grew up with a Protestant mom and Catholic dad.

I loved Surrender. You get to observe the band in the process of creating some of their most iconic songs. The book is filled with clever, self-deprecating lines like “Just how effective can a singer with anger issues be in the cause of nonviolence?” And you’ll learn a lot about the challenges he dealt with in his campaigns for debt relief and HIV treatment in Africa. (The Gates Foundation is a major supporter of ONE, the nonprofit that Bono helped start.)

In this passage, he explains how a boy from the suburbs of Dublin became a global phenomenon: “There are only a few routes to making a grandstanding stadium singer out of a small child. You can tell them they’re amazing, that the world needs to hear their voice, that they must not hide their ‘genius under a bushel.’ Or you can just plain ignore them. That might be more effective. The lack of interest of my father, a tenor, in his son’s voice is not easy to explain, but it might have been crucial.” (It also helped that he has, as he later learned from a doctor, freakishly large lung capacity.)

Bono’s loyalty to his bandmates, and their loyalty to him, is pretty incredible. My favorite illustration from the book takes place at a concert in Arizona, when the band was urging the then-governor to uphold the national MLK Day holiday in his state. U2’s security team picked up a credible threat to Bono’s life if the band played their Martin Luther King tribute “Pride (In the Name of Love).” “It wasn’t just melodrama,” he writes, “when I closed my eyes and sort of half kneeled to disguise the fact that I was fearful to sing the rest of the words.” When Bono opened his eyes, he saw that bassist Adam Clayton had moved in front of him to shield him like a Secret Service agent. Fortunately, the threat never materialized.

There’s another factor that explains the band’s tight bonds: They share the same values. All four of them are passionate about fighting poverty and inequity in the world, and they’re also aligned on maintaining their integrity as artists. I learned this the hard way. When Microsoft wanted to license U2’s song “Beautiful Day” for an ad campaign, I joined a call in an attempt to persuade the band to go for the deal. They simply weren’t interested. I admired their commitment.

While Bono never got lost in drugs or alcohol, he acknowledges that stardom gave him a big ego. He also says that he had a “need to be needed.” His key to survival was embracing the concept of spiritual surrender, as the title of the book suggests. He eventually came to see that he’d never fill his emotional needs by playing for huge crowds or being a global advocate. His faith in a higher power helped him a lot. So did his wife, Ali. He writes that when his mom died during his childhood, his home “stopped being a home; it was just a house.” Ali and their four children gave him a home once again.

Bono writes that his surrender is still incomplete. He’s not going to retire anytime soon, which is great news and not just for U2 fans. After the past few years, the field of global health—one of his chief causes—needs an injection of energy and passion. Bono’s unique gifts are perfectly suited to that mission.

Diller instinct

The man who built modern media

Barry Diller’s memoir is a candid playbook for creativity and competition in business.

If you don’t know Barry Diller’s name, you definitely know his work.

He invented the made-for-TV movie and the TV miniseries. He greenlit Raiders of the Lost Ark, An Officer and a Gentleman, Grease, Saturday Night Fever, Terms of Endearment, and the Star Trek movies. He created the Fox television network and helped bring the world The Simpsons. He turned QVC into a home shopping behemoth. He assembled a digital empire that built or grew Expedia, Match.com, Ticketmaster, Vimeo, and many more companies now part of everyday online life.

And that’s just scratching the surface.

I’m lucky to call Barry a friend, and I thought I knew his story. But his new memoir Who Knew still managed to surprise and teach me a lot about him, his career, and the many industries he’s transformed.

The book opens with Barry’s complicated childhood in Beverly Hills. From the outside, his family life looked idyllic. But his brother struggled with addiction; his parents, though loving, were often emotionally distant and preoccupied. Meanwhile, Barry was grappling with his sexuality in an age when being gay meant living in constant fear of exposure.

This part of Who Knew is raw and honest in a way most business memoirs usually aren’t. But Barry’s early years are key to understanding not just who he became as a person but also how he succeeded professionally. Reading the book, you can see how the same coping mechanisms he developed as a kid—learning to read people, defuse tension, compartmentalize, adapt—evolved into business instincts later on.

After barely graduating high school, Barry started in the mailroom of William Morris, a talent agency, at 19. Most people trying to break into Hollywood treat the mailroom as a stepping stone. The goal is to get out fast, become someone’s assistant, then get promoted to agent yourself. But Barry spent years there by choice, reading every contract and deal memo in the agency’s history. (His obsessive self-education reminded me of my own approach to learning.)

By the time he joined ABC at 23, he knew more about how the entertainment industry actually worked—the deal structures, the power dynamics, who mattered and why—than executives twice his age. That foundation let him revolutionize an industry in ways you can only do when you truly understand it.

At ABC, Barry came up with the made-for-TV movie: 90-minute films produced specifically for television, with different stories and casts each week. Within a year, ABC was producing 75 original movies annually. By 27, Barry was the youngest vice president in network television history. Then he created the miniseries.

Five years later, he was named chairman of Paramount Pictures, which had fallen to fifth place among the major movie studios. Barry rebuilt it into the number one studio by focusing on ideas first, not pre-packaged deals that came with the stars, directors, and writers already attached. He built a team of young executives and put them through what he called “creative conflict”: exhausting late-night sessions where his team would tear ideas apart to find their essence. Only if an idea survived that process would they develop it and then attach the right talent.

After leaving Paramount, Barry joined 20th Century Fox as chairman. But what he really wanted to do at Fox was create something that didn’t exist yet: a fourth national network to rival ABC, CBS, and NBC. That’s probably what surprised me most in the book—learning that Fox Broadcasting was Barry’s idea, not Rupert Murdoch’s. Barry had been pitching a fourth network for nearly a decade, even though conventional wisdom said that America could only support three networks. But Barry thought they’d become homogenous and identified an opening for something new. Eventually, he got Murdoch to agree.

That pattern shows up throughout the book. Barry is able to see opportunities that are invisible to everyone else and sound crazy until they don’t. When he left Fox at its peak to run QVC, people were baffled, including me. In reality, Barry had recognized that the future of commerce was hiding in plain sight, on a home shopping channel, where phone calls spiked in real-time as products were pitched on TV. This epiphany about interactivity—screens as two-way, not just passive—helped Barry do super well in the digital era.

Barry was early to see the internet’s potential and willing to bet on it when others weren’t. In 2001, he was in the process of buying Expedia from Microsoft when 9/11 happened and air travel grounded to a halt. He had an out clause but decided to go through with the acquisition anyway, betting that travel would come back. It did, and Expedia became one of the first major successes in what would become IAC: the unlikely conglomerate of 150+ internet businesses Barry assembled over the next two decades.

I’ve always wondered why one studio succeeds while another fails, and how revolutionary ideas get greenlit when conventional wisdom says they’re impossible. Barry provides a lot of insight, especially about media and entertainment, that I didn’t know before. He’s also candid about his failures: the disastrous stint running ABC’s prime-time programming, getting outmaneuvered in bidding wars, trusting the wrong people. I like that Barry doesn’t gloss over mistakes or reframe them as “learning experiences.” He just tells you he screwed up.

In his book, Barry attributes much of his success to luck and timing. But there’s a difference between being in the right place at the right time and knowing what to do once you’re there.

Who Knew? Barry did. He just had to wait for everyone else to catch up.

Field notes

The world needs more Nick Kristofs

I loved this journalist’s story of chasing hard problems and holding onto hope.

If you’re a big reader, you can probably point to a book or two that changed the course of your life. For me, it was a 1997 New York Times column by Nicholas Kristof about diarrhea, which was killing three million kids a year.

At the time, I had wealth—and knew I planned to give it away—but no clear mission. Nick’s article gave me one. I faxed it to my dad with a note: “Maybe we can do something about this.”

That ended up setting the direction for what became the Gates Foundation. It didn’t just give us a what—it gave us a how. Nick’s reporting showed us that the biggest challenge in global health isn’t always discovering new breakthroughs. Often, it’s making sure the tools we already have—vaccines, medicines, bed nets, or oral rehydration therapies for rotavirus—reach every child, no matter where they’re born.

Reading Nick’s new memoir, Chasing Hope, brought me back to that moment and showed me how it fit into the bigger story of his life. The book is a deeply personal account of a life spent documenting injustice and refusing to look away, whether it’s genocide in Darfur, refugee camps in Sudan, or the streets of his hometown in rural Oregon.

Nick’s impulse to go where the suffering is, and to make people care, has defined his career. He’s reported from more than 150 countries, covering war, poverty, health, and human rights. He and his longtime collaborator and wife, Sheryl WuDunn, won a Pulitzer Prize for their work. Together and individually, they’ve brought injustices around the world into view for millions of readers.

But Chasing Hope isn’t just a greatest-hits collection of his past reporting. It’s the story of how someone becomes Nick Kristof. He writes about growing up on a sheep and cherry farm in Oregon, driving tractors as a teenager, and nearly becoming a lawyer before deciding on journalism. He also reflects on the toll his career has taken on him, his family, and his capacity for hope.

I’ve known Nick for many years now, and I’ve admired his work since that 1997 rotavirus column. On paper, we don’t seem all that similar. He’s a journalist, I’m a technologist; he tells stories, I talk numbers. But reading Chasing Hope, I was struck by what we have in common: growing up in the Pacific Northwest, learning about the value of service from our parents, thinking globally.

We both attended Harvard and left early—me because I dropped out, him because he graduated in three years before heading to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. But neither of us ever stopped learning. I think we both believe the world’s pretty interesting if you remain a student.

Nick’s curiosity didn’t come out of nowhere, and neither did his sense of purpose. His mother was an art history professor and a civic leader who helped influence local politics. His father, a political science professor who fled both Nazism and communism, believed deeply in education and the responsibilities that come with freedom. That kind of upbringing left a mark on him and shaped the kind of journalist he became.

Over decades, he’s built a career reporting on crises that are often ignored because they happen in far-off places, far from centers of power. In Chasing Hope, he recounts his experiences chronicling river blindness in Ethiopia, maternal mortality in Cameroon, and malaria in Cambodia. Through the foundation, I mobilize science, data, and funding to address many of the same global challenges Nick reports on. Our approaches are different, but the underlying questions we ask (and try to answer) are the same: Why are some lives valued less than others? And how can we use the tools we have—information, resources, attention—to close that gap?

Nick has an admirable commitment to nuance, especially when it comes to hard subjects like China. Nick lived there for years, speaks Mandarin, and understands the country in a way most Western commentators don’t. I’ve always appreciated his ability to go beyond the headlines—and focus not just on what’s going wrong, but on what’s changing and why it matters.

Nick is also an optimist, which might sound strange given the kinds of suffering he writes about. But his work is grounded in a belief I share: The right data—or the right story—can move people to act. As Nick puts it, “A central job of a journalist is to get people to care about some problem that may seem remote.” People, when given the chance, want to make things better. Progress, while never guaranteed, is possible.

That optimism feels especially important, if increasingly difficult, right now. Isolationism is on the rise around the world, and governments are cutting back on foreign aid at the very moment when we should be doing more, not less. Millions of lives are at stake. Nick’s work reminds us what’s possible when we care about people beyond our own borders—and what happens when we don’t.

Chasing Hope made me think a lot about what kind of person chooses to run toward the hardest problems—and keep going back until they’re solved. It also made me think the world would be a much better place if there were more Nick Kristofs. In the meantime, we’re lucky to have this one.

On the record

How Katharine Graham found the courage to challenge Nixon

Personal History contains valuable lessons about leadership and finding strength in vulnerability.

July 5, 1991 was one of the most important days of my life. My mom was hosting a get-together at our family’s favorite vacation spot in Hood Canal, WA. One of her friends had invited Warren Buffett, and I immediately hit it off with him, kickstarting a relationship that would, among other things, lead to the creation of the Gates Foundation.

But Warren wasn’t the only legend in the room. I remember him introducing me to his old friend Katharine Graham, one of the most well-respected newspaper publishers in the world. Even after all these years—and after her death in 2001—I still treasure the friendship I began with Kay that day.

Kay is best known for leading the Washington Post through the Watergate crisis, but her remarkable story goes way beyond her fights with the Nixon White House. That story is told in her riveting memoir Personal History, which came out in 1997—just a few years before she passed away—and won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Kay’s father purchased the Washington Post and saved it from bankruptcy when she was a teenager. In 1946, he made Kay’s husband, Philip Graham, the publisher of the paper. Although this decision sounds strange today—Why would you hand over the family business to your son-in-law instead of your own child?—the thought of putting a woman in charge was unthinkable in that era. “It never crossed my mind that he might have viewed me as someone to take on an important job at the paper,” she writes. Kay was expected to devote her life to being a good wife and mother.

But life with Phil wasn’t easy. He suffered from bipolar disorder at a time when treatments for mental illness were crude and ineffective. The chapters about his mental decline are devastating. Kay describes how Phil had to be sedated after suffering from a manic episode at a publishing conference. A few months later, he dies by suicide during a stay at the family’s country home. Kay is the first person to find his body.

While she was struggling with grief, Kay found herself thrust into a new role: president of the Washington Post Company and the publisher of a major national newspaper. That isn’t an easy job under any circumstances, but several of Kay’s male colleagues made it harder than it needed to be. “I didn’t blame my male colleagues for condescending—I just thought it was due to my being so new,” she writes. “It took the passage of time and the women’s lib years to alert me properly to the real problems of women in the workplace, including my own.”

Still, Kay internalized some of the skepticism, and she is pretty harsh on herself throughout the book. She blames herself for Phil’s suicide and describes her business acumen as “abysmally ignorant” when she takes over the Post. I understand her impulse to be critical of her younger self—I often felt frustrated by how I acted as a kid when I was writing my own memoir, Source Code. But it can be difficult to read at points in Personal History. I wish Kay knew how special she was.

Her story is a powerful reminder that strong leaders don’t always come in the form you expect. What Kay sees as weaknesses end up becoming her strengths. Because she didn’t know much about the newsroom when she took over in 1963, she asked a lot of questions. A more experienced publisher might have come into the job with preconceived notions about how to run things—but Kay listened to her new colleagues, and she took the time to learn how they worked. That trust in her people would pay off years later during the Watergate scandal.

I was a teenager during the Watergate years, and I remember reading about it in the paper. Many people focus on two specific events when they talk about Watergate: the break-in at the Democratic National Committee in June 1972, and President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 after secret recordings revealed his administration’s involvement in the burglary and subsequent cover-up. But during the more than two years between those two points, the Washington Post reported relentlessly on the scandal.

Nixon himself tried to bully them into giving up, but Kay stood by her newsroom. She protected their editorial independence, never asking her reporters to censor or soften their reporting. At one point, John Mitchell—the chair of Nixon’s re-election campaign and former Attorney General—told a Post reporter that Kay was going to get a certain part of her anatomy “caught in a big fat ringer.” She read about it in the paper the next day.

Kay risked the company’s reputation and financial health to protect journalistic integrity, even in the face of potential lawsuits and calls to discredit the paper. The Post almost folded at one point when the Nixon administration threatened to pull the broadcasting licenses for several TV stations owned by the Washington Post Company. (Despite being the namesake of the company, the Washington Post itself was not profitable at the time. The business relied on local broadcast stations to stay afloat.)

This is where Warren enters the story. He believed the Washington Post was undervalued, and in 1973, Berkshire Hathaway bought a 10 percent ownership share—enough to keep the company going while making sure that Kay remained in control. He eventually became a trusted advisor and a close friend to Kay, which I saw firsthand years later in Hood Canal.

Warren has always hated that Kay was left out of the movie All the President’s Men, which came out just two years after Nixon resigned and received great critical acclaim. Without her leadership and bravery, the Watergate scandal might have faded into obscurity. Fortunately, the film The Post gave Kay her proper due. Meryl Streep was even nominated for an Oscar for playing her.

There is so much to Kay’s story—including her time with President Kennedy, the Pentagon Papers, and the pressmen’s strike—that I cannot mention all of it here. If you want to learn even more about her incredible life, I recommend starting with the new documentary Becoming Katharine Graham before reading Personal History.

Diving deep into Kay's extraordinary life is well worth your time. Her story offers more than just insights into a fascinating chapter of American history—it also reveals valuable lessons about courage, leadership, and finding strength in vulnerability.

Universal humor

Chameleon comic

Trevor Noah’s funny and moving account of growing up in South Africa.

I’m a longtime fan of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. When Jon Stewart stepped down as host in 2015, I was sad to see him go. I was also worried for his replacement, Trevor Noah, a South African comedian. Stewart’s style is so unusual that I didn’t see how anyone could fill his shoes—especially someone like Noah, who describes himself as an outsider. As popular as Noah was in South Africa, I didn’t know whether his humor would connect with American audiences.

I’m happy to report that I was wrong. Millions of viewers—myself included—are tuning in to The Daily Show because Noah’s show is every bit as good as Stewart’s. His humor has a lightness and optimism that’s refreshing to watch. What’s most impressive is how he uses his outside perspective to his advantage. He’s good at making fun of himself, America, and the rest of the world. His comedy is so universal that it has the power to transcend borders.

Reading Noah’s memoir, Born a Crime, I quickly learned how Noah’s outsider approach has been honed over a lifetime of never quite fitting in. Born to a black South African mother and a white Swiss father in apartheid South Africa, he entered the world as a biracial child in a country where mixed race relationships were forbidden. Noah was not just a misfit, he was (as the title says) “born a crime.”

In South Africa, where race categories are so arbitrary and yet so prominent, Noah never had a group to call his own. As a little boy living under apartheid laws, he couldn’t be seen in public with his white father or his black mother. In public, his father would walk far ahead of him to ensure he wouldn’t be seen with his biracial son. His mother would pose as a maid to make it look like she was just babysitting another family’s child. On the schoolyard, he didn’t fit in with the white kids or the black kids or the kids who were “colored” (the term used in South Africa to describe people of mixed race).

But during his childhood, he quickly discovered that there’s a freedom that comes with being a misfit. A polyglot who speaks English, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu, Tsonga, Tswana, as well as German and Spanish, Noah used his talent for language to bounce from group to group and win acceptance from all of them. One of my favorite stories in the book involves Noah walking down the street when he overhears a group of men speaking in Zulu about how they were plotting to mug “this white guy.” Noah realizes they were referring to him. Noah spins around and announces in perfect Zulu that they should all mug someone together. The Zulu men are startled that Noah speaks Zulu and a tense situation is defused. Noah is immediately accepted as one of their own.

Again and again throughout his childhood, he discovered that language was more powerful than skin color in building connections with other people. “I became a chameleon,” Noah writes. “My color didn’t change, but I could change your perception of my color. If you spoke to me in Zulu, I replied to you in Zulu. If you spoke to me in Tswana, I replied to you in Tswana. Maybe I didn’t look like you, but if I spoke like you, I was you.”

Much of Noah’s story of growing up in South Africa is tragic. His Swiss father moves away. His family is desperately poor. He’s arrested. And in the most shocking moment, his mother is shot by his stepfather. Yet in Noah’s hands, these moving stories are told in a way that will often leave you laughing. His skill for comedy is clearly inherited from his mother. Even after she’s shot in the face, and miraculously survives, she tells her son from her hospital bed to look at the bright side. “’Now you’re officially the best-looking person in the family,’” she jokes.

In fact, Noah’s mother emerges as the real hero of the book. She’s an extraordinary person who is fiercely independent and raised her son to be the same way. Her greatest gift was to give her son the ability to think for himself and see the world from his own perspective. “If my mother had one goal, it was to free my mind,” he writes. Like many fans of Noah’s, I am thankful she did.

Quest for knowledge

Educated is even better than you’ve heard

I loved Tara Westover’s journey from the mountains of Idaho to the halls of Cambridge.

I’ve always prided myself on my ability to teach myself things. Whenever I don’t know a lot about something, I’ll read a textbook or watch an online course until I do.

I thought I was pretty good at teaching myself—until I read Tara Westover’s memoir Educated. Her ability to learn on her own blows mine right out of the water. I was thrilled to sit down with her recently to talk about the book.

Tara was raised in a Mormon survivalist home in rural Idaho. Her dad had very non-mainstream views about the government. He believed doomsday was coming, and that the family should interact with the health and education systems as little as possible. As a result, she didn’t step foot in a classroom until she was 17, and major medical crises went untreated (her mother suffered a brain injury in a car accident and never fully recovered).

Because Tara and her six siblings worked at their father’s junkyard from a young age, none of them received any kind of proper homeschooling. She had to teach herself algebra and trigonometry and self-studied for the ACT, which she did well enough on to gain admission to Brigham Young University. Eventually, she earned her doctorate in intellectual history from Cambridge University. (Full disclosure: she was a Gates Scholar, which I didn’t even know until I reached that part of the book.)

Educated is an amazing story, and I get why it’s spent so much time on the top of the New York Times bestseller list. It reminded me in some ways of the Netflix documentary Wild, Wild Country, which I recently watched. Both explore people who remove themselves from society because they have these beliefs and knowledge that they think make them more enlightened. Their belief systems benefit from their separateness, and you’re forced to be either in or out.

But unlike Wild, Wild Country—which revels in the strangeness of its subjects—Educated doesn’t feel voyeuristic. Tara is never cruel, even when she’s writing about some of her father’s most fringe beliefs. It’s clear that her whole family, including her mom and dad, is energetic and talented. Whatever their ideas are, they pursue them.

Of the seven Westover siblings, three of them—including Tara—left home, and all three have earned Ph.D.s. Three doctorates in one family would be remarkable even for a more “conventional” household. I think there must’ve been something about their childhood that gave them a degree of toughness and helped them persevere. Her dad taught the kids that they could teach themselves anything, and Tara’s success is a testament to that.

I found it fascinating how it took studying philosophy and history in school for Tara to trust her own perception of the world. Because she never went to school, her worldview was entirely shaped by her dad. He believed in conspiracy theories, and so she did, too. It wasn’t until she went to BYU that she realized there were other perspectives on things her dad had presented as fact. For example, she had never heard of the Holocaust until her art history professor mentioned it. She had to research the subject to form her own opinion that was separate from her dad’s.

Her experience is an extreme version of something everyone goes through with their parents. At some point in your childhood, you go from thinking they know everything to seeing them as adults with limitations. I’m sad that Tara is estranged from a lot of her family because of this process, but the path she’s taken and the life she’s built for herself are truly inspiring.

When you meet her, you don’t have any impression of all the turmoil she’s gone through. She’s so articulate about the traumas of her childhood, including the physical abuse she suffered at the hands of one brother. I was impressed by how she talks so candidly about how naïve she once was—most of us find it difficult to talk about our own ignorance.

I was especially interested to hear her take on polarization in America. Although it’s not a political book, Educated touches on a number of the divides in our country: red states versus blue states, rural versus urban, college-educated versus not. Since she’s spent her whole life moving between these worlds, I asked Tara what she thought. She told me she was disappointed in what she called the “breaking of charity”—an idea that comes from the Salem witch trials and refers to the moment when two members of the same group break apart and become different tribes.

“I worry that education is becoming a stick that some people use to beat other people into submission or becoming something that people feel arrogant about,” she said. “I think education is really just a process of self-discovery—of developing a sense of self and what you think. I think of [it] as this great mechanism of connecting and equalizing.”

Tara’s process of self-discovery is beautifully captured in Educated. It’s the kind of book that I think everyone will enjoy, no matter what genre you usually pick up. She’s a talented writer, and I suspect this book isn’t the last we’ll hear from her. I can’t wait to see what she does next.

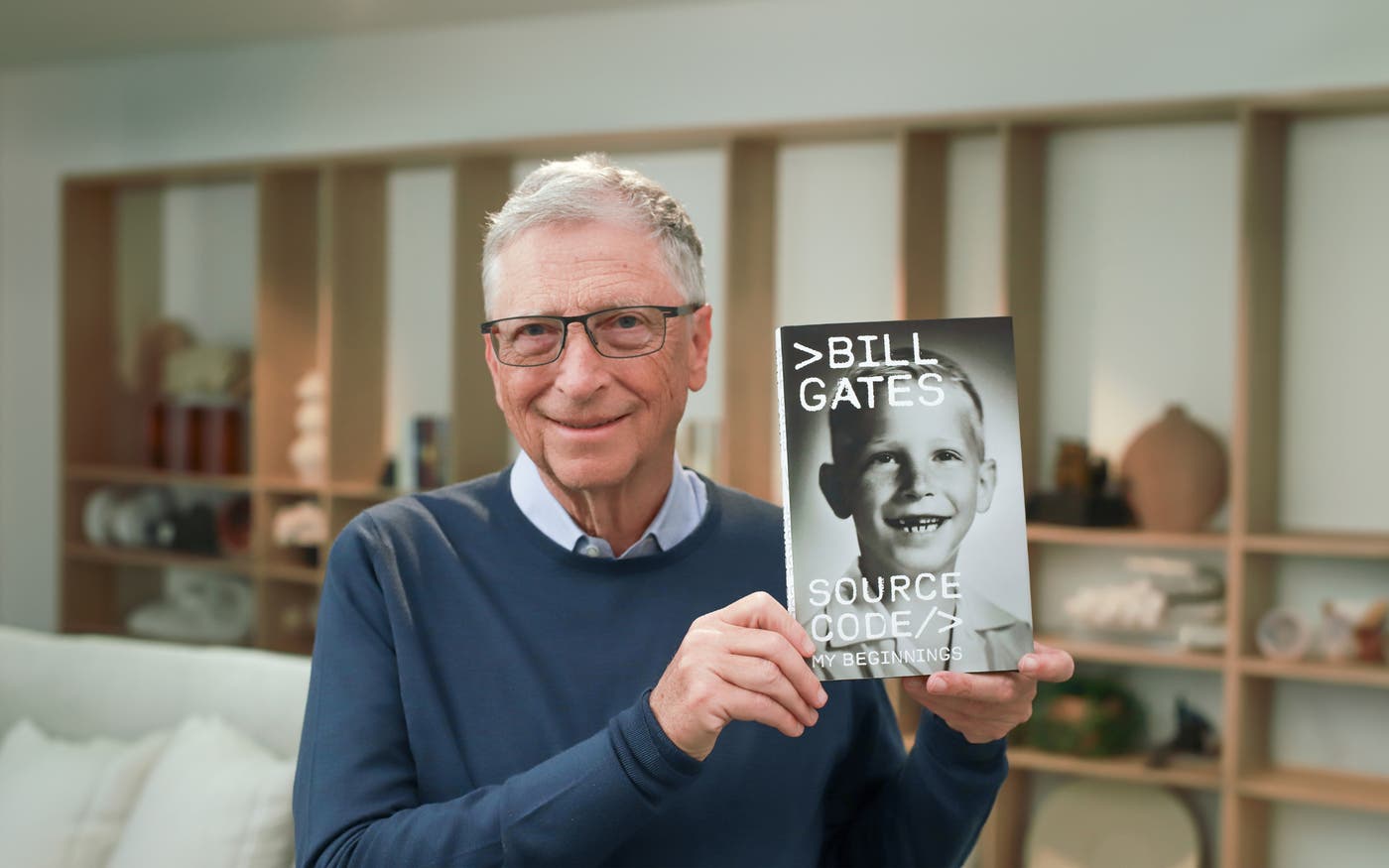

Starting line

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

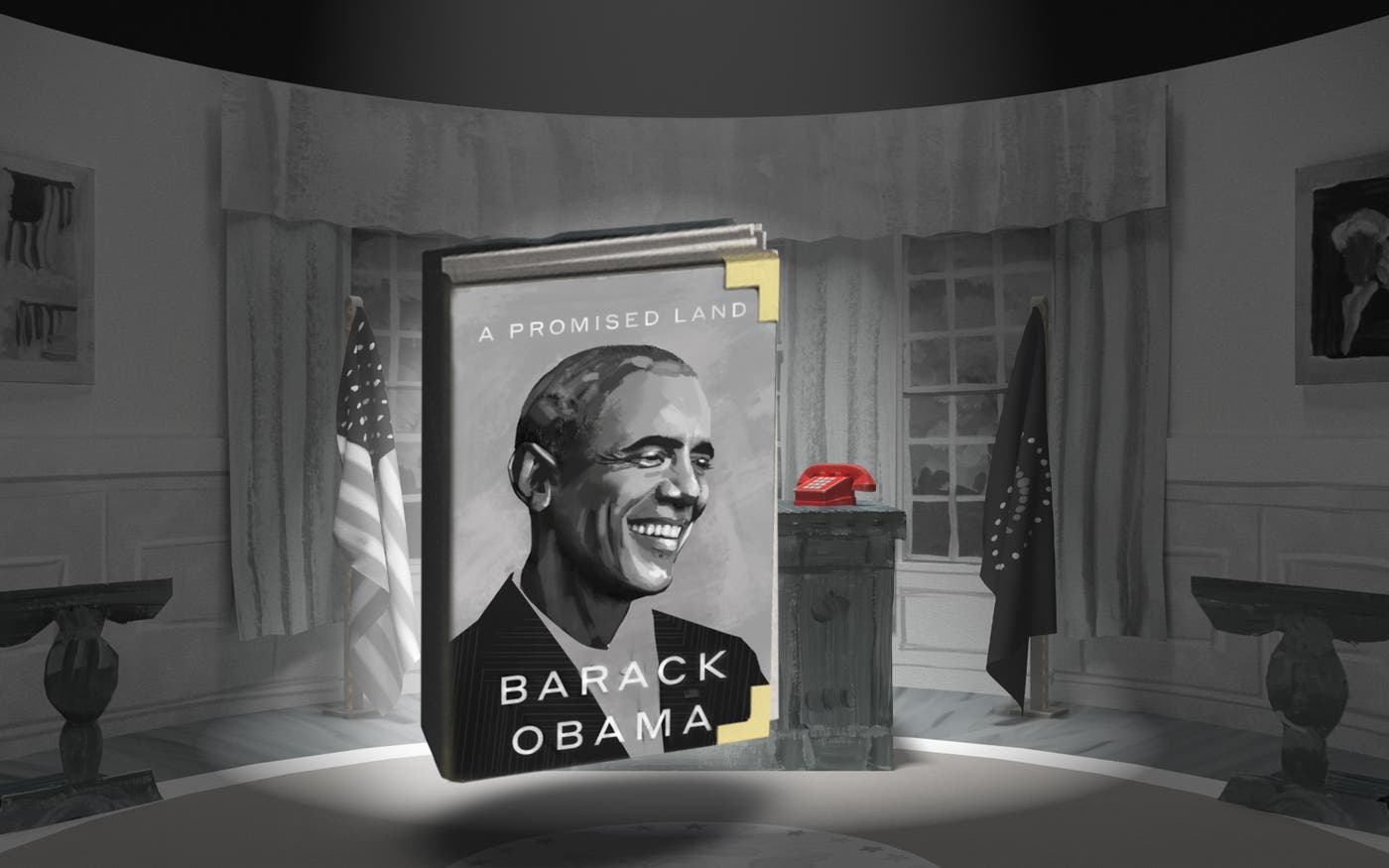

Hail to the chief

A refreshingly honest take on the American presidency

President Obama’s memoir is a terrific read, no matter what your politics are.

I’m a big fan of presidential memoirs, but they tend to follow the same script. The author usually touts things that went well or repeats talking points you’ve heard from them before. I think the best writing about presidents is often done by a third party, because they’re able to be more objective. (The Bully Pulpit and Presidents of War are some of the best books I’ve read.)

You have to be a pretty self-aware person to write a candid autobiography—something that politicians aren’t exactly known for. Fortunately, President Obama isn’t like most politicians. A Promised Land is a refreshingly honest book. He isn’t trying to sell himself to you or claim he didn’t make mistakes. It’s a terrific read, no matter what your politics are.

The book covers Obama’s life up through the operation that killed Osama bin Laden in 2011. I found the parts about his early career to be particularly interesting. He does an excellent job describing how challenging he found politics, especially when he was just starting out. I liked him before I read the book but even more after reading it.

Most people think of Obama as a natural politician because he’s so good at public speaking. But he didn’t enjoy campaigning the way Bill Clinton did, and he preferred sitting in policy briefings to shaking hands and kissing babies. He was especially uncomfortable with the adoration that he got in 2008, writing that he had to “constantly take stock to make sure I wasn’t buying into the hype and remind myself of the distance between the airbrushed image and the flawed, often uncertain person I was.”

I wish more politicians could write like Obama. A Promised Land almost reads like a novel, because he’s so good at connecting each individual event into one big narrative. The book—which is the first of a planned two volumes—covers some of his biggest accomplishments, including the 2009 stimulus package and the Affordable Care Act. Even though you already know that both of those bills become law, his honest assessments turn them into compelling stories that keep you on the edge of your seat.

Obama has a very lawyerly approach to thinking and writing about policy, which I like. He talks at length about how his staff would get frustrated by his need to understand all of the facts and every side of the argument. I loved how he describes seeking out different points of view and how they influenced the choices he made. The chapter about his disagreements with the generals over his decision to withdraw from Iraq is fascinating (and is especially interesting in light of President Biden’s decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan later this year).

The book captures how complex the job of running the country is. You’re constantly shifting gears, even more than a CEO does. As president, your day is all about making monumental decisions that affect many people’s lives and livelihoods, and you have to focus on many problems at once. Obama says he found it difficult to stay focused and not get pulled into different crises all the time. Toward the end of the book, he recalls flying to Alabama to survey the damage from a deadly tornado right after giving the green light for the bin Laden raid. I was impressed by his ability to approach such radically different situations with equal attention and care.

Obama makes it clear the positives of the job—especially the opportunity to make lives better—outweigh the negatives. But overall, the memoir left me with a surprisingly melancholy impression of what it’s like to be the president. “Sometimes I’d fantasize about walking out the east door and down the driveway, past the guardhouse and wrought-iron gates, to lose myself in crowded streets and reenter the life I’d once known,” he writes.

A Promised Land is ultimately a story about how the presidency defines the lives of those wrapped up in it. “For all its power and pomp,” Obama says, “the presidency is still just a job and our federal government is a human enterprise like any other.” I can’t wait to get another peek behind the curtain when the second book comes out.

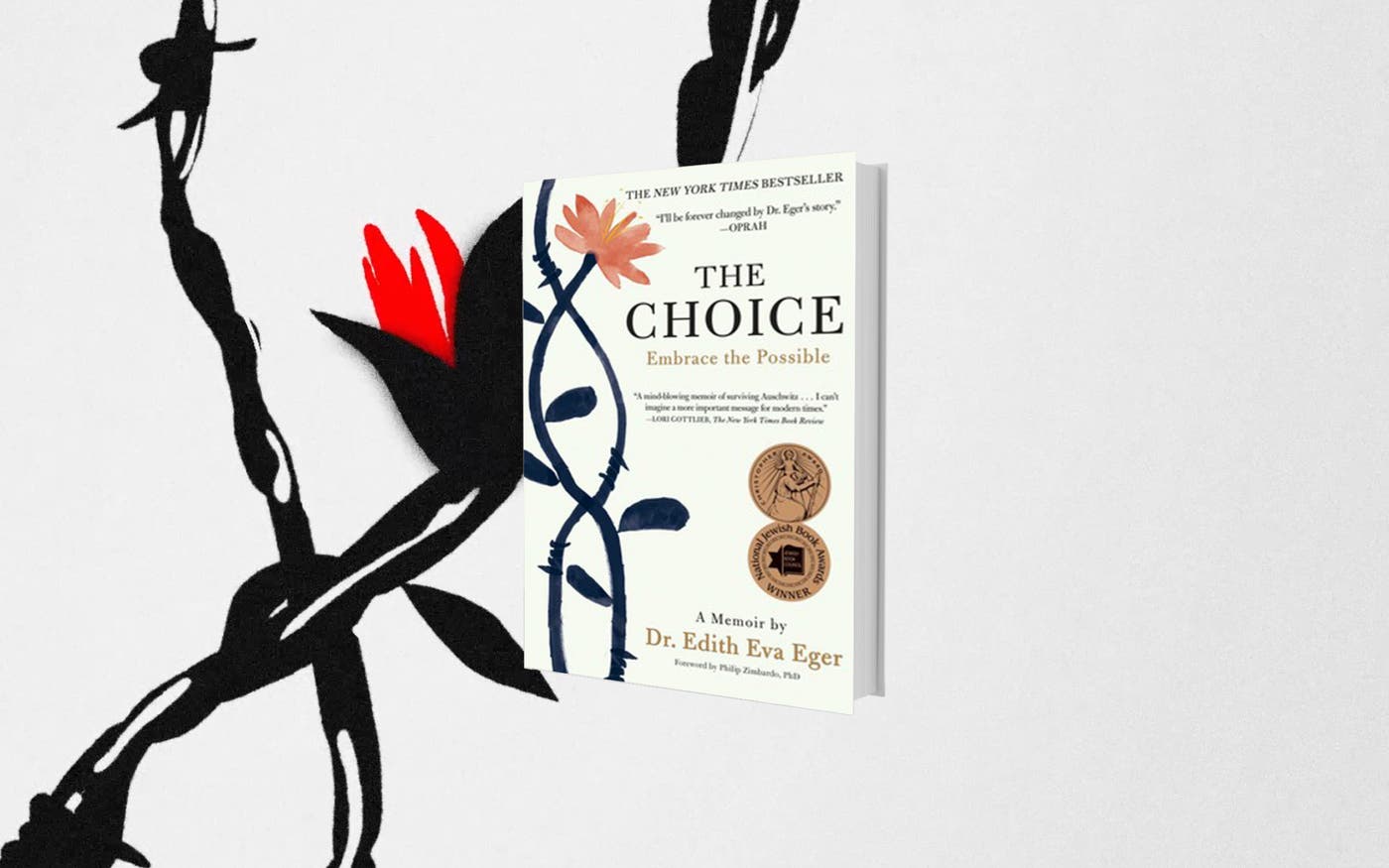

Getting better

An Auschwitz survivor’s guide to healing

Eger’s life story gives her fascinating insight into how people move on after trauma.

How do you move on after trauma?

That’s a question many of us will unfortunately have to grapple with at some point in our lives. It’s certainly relevant right now. The good news is that there is no shortage of smart, thoughtful people out there offering advice on the subject. I recently read a book by Dr. Edith Eva Eger that I think is particularly useful.

The Choice is partly a memoir and partly a guide to processing trauma. Melinda recommended that I read it, and I’m glad she did. What makes the book exceptional is Edith’s life story: she’s an Auschwitz survivor and a professional therapist. That combination gives her fascinating insight into how people heal.

Edith was just a teenager when her family was taken from their home in Hungary and sent to the death camp at Auschwitz. She was separated from her parents, whom she never saw again. Edith and her sister Magda managed to stay together, though, and they spent the next year helping each other survive unbelievable horrors.

Even after the sisters are liberated, Edith’s trauma doesn’t end. I don’t want to give away specifics, but the book offers a look into how chaotic the post-war period was in Europe. Her story is a reminder of how people’s worst instincts can come out when civil order is completely broken down. Edith remained a victim long after her rescue, even as she’s supposed to be healing from the physical trauma she sustained at Auschwitz.

Eventually, though, Edith met the man who became her husband and moved to the United States. After a rough couple of years, she started a family and learned enough English to begin studying psychology at the University of Texas, El Paso. Her past continued to haunt her, though—she often found herself paralyzed by memories of the concentration camp.

Everything changed when a fellow student gave her a copy of Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl was a prisoner at Auschwitz at the same time as Edith, and his writing becomes the inspiration for her philosophy as a therapist. The lesson she says she took from it is that “each moment is a choice. No matter how frustrating or boring or constraining or painful or oppressive our experience, we can always choose how we respond.” (I read Man’s Search for Meaning many years ago, and I completely understand why it made such an impact on Edith.)

Edith begins processing her past--she even returns to visit Auschwitz as part of the healing process. All the while, she builds a career as a successful therapist who specializes in trauma. This is when the book starts to become more of a guide. She talks a lot about her patients, some of whom suffer from PTSD and have really tragic stories. But not all of her patients have experienced huge traumas.

I think it’s important to point out that her approach applies to everyday disappointments, too. In one memorable story at the beginning of the book, Edith talks about a patient who cried over the fact that her new car was the wrong shade of yellow. Your first reaction as a reader is to see the woman as petty. How can she be upset over a such a silly thing when there is real suffering in the world?

Edith doesn’t see it that way, though. She saw that “her tears of disappointment over the car were really tears of disappointment over the bigger things in her life that hadn’t worked out the way she had hoped.” The patient was transferring her emotional isolation to material disappointment. Edith makes a sympathetic and understandable case that there was something missing in that woman’s life that made her latch onto seemingly silly points of validation. She treats the patient’s pain as seriously as she would anyone else’s.

I really like her approach, because it implies that there is a path to getting better no matter what you’re going through. People can struggle and feel worthless without extreme things happening. That pain is still worthy of attention and help.

It’s a good reminder that there is no “hierarchy of suffering,” as Edith calls it. If you’re struggling with something, that struggle is real—even if you think your experience feels trivial compared to the experience of someone who survived Auschwitz or someone whose child is suffering from a terrible disease. I think this is an especially important thing to keep in mind right now while everyone has different experiences with the COVID-19 outbreak.

Although Edith’s early life is what will make you pick up The Choice, her insights as a therapist are what will stick with you long after you finish it. I hope it gives you some comfort in these challenging times.

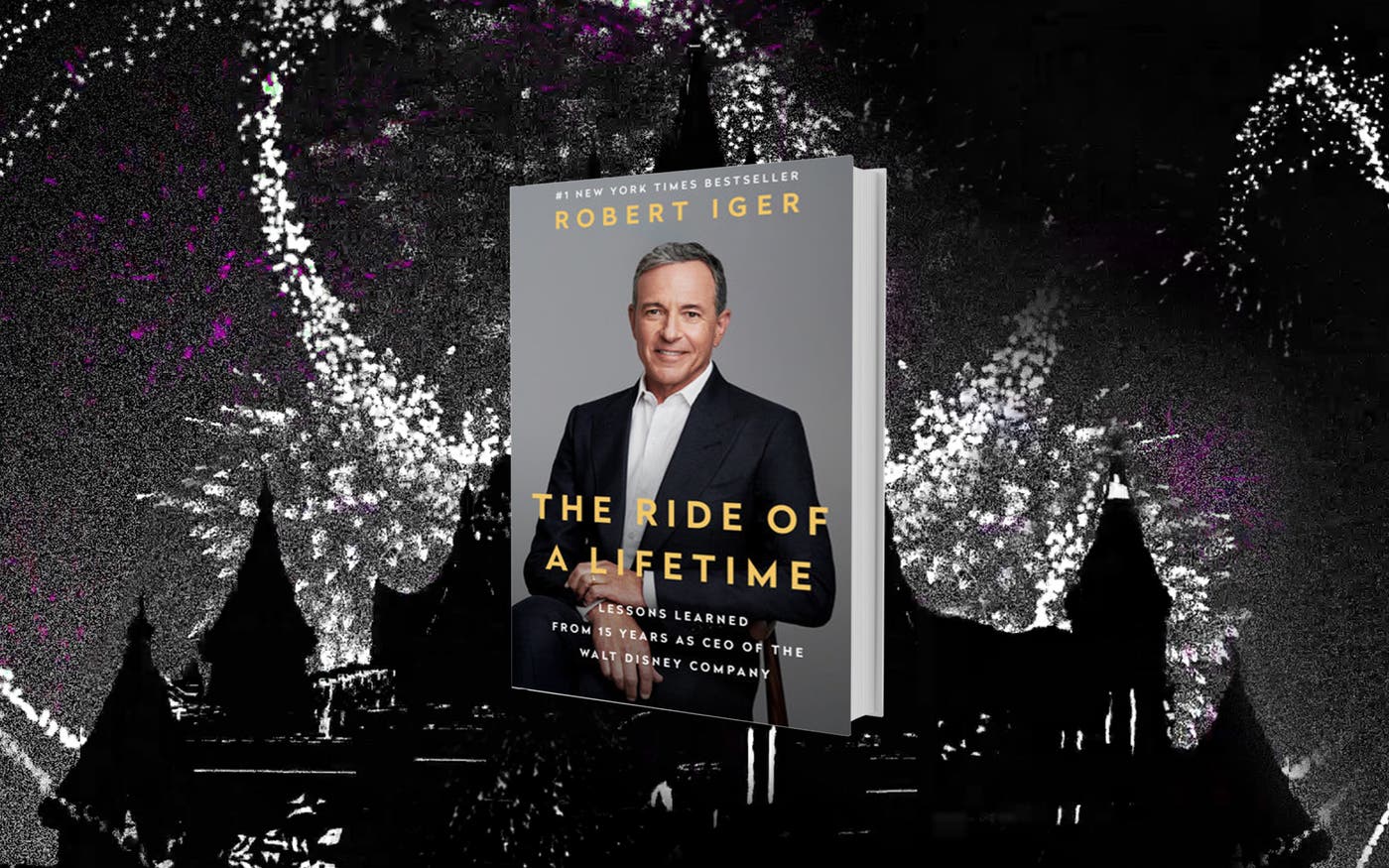

Disney heights

A business book I’d actually recommend

Unlike most books on leadership, this one is worth your time.

I don’t read many books about how to run a business. In my experience, it is rare to find one that really captures what it’s like to build and operate an organization or that has tips you could really put into practice.

It’s still the case that the best business book I have ever read is Business Adventures, a little-known collection of articles by a reporter named John Brooks. Whenever someone asks me to recommend one book on business, that’s the one I suggest most often.

But I recently read another business book that I will happily recommend to anyone who asks: The Ride of a Lifetime, by former Disney CEO Robert Iger. In fact, I have already suggested it to several friends and colleagues, including Satya Nadella.

As the person who led Disney’s acquisition of Pixar, Lucasfilm (that is, all the Star Wars stuff), Marvel, and most of 21st Century Fox, Iger is able to take you inside the workings of a massive media company and show how he thought about building on its strengths and shoring up its weaknesses. This is a short, readable book with smart insights, and along the way he crosses paths with some colorful characters.

Iger does a great job explaining what it is like to be a CEO. You’re always worried, “Which thing am I not spending enough time on?” As Iger writes, “You go from plotting growth strategy with investors, to looking at the design of a giant new theme-park attraction with Imagineers, to giving notes on the rough cut of a film, to discussing security measures and board governance and ticket pricing and pay scale... there are also, always, crises and failures for which you can never be fully prepared.” Although I never had to deal with most of those specific issues, the overall picture he draws is quite accurate.

One of the most memorable parts of the book occurs in 2006, shortly after Iger becomes Disney’s CEO. Although the company had built its reputation on animation (including old classics like Snow White and modern ones like the original Lion King), by the time Iger took over, Disney had experienced a long series of box-office disappointments. Rather than trying to rebuild the studio, Iger decides to try to buy the most successful animation company out there: Pixar, whose CEO and majority owner was Apple co-founder Steve Jobs.

Iger takes you through all the twists and turns of the negotiations with Steve. Some people thought the $7 billion-plus price tag they settled on was too high, but Iger was convinced it was the only way to go. No one else had managed to solve the problem by rebuilding from within, and Iger didn’t think he could do it either.

There’s an especially dramatic and poignant moment near the end of the story. Just 30 minutes before the press conference where they will announce this massive merger, Steve takes Iger aside and shares some crushing news that only his wife and doctors know: After years in remission, his pancreatic cancer has returned and spread to his liver.

“I am about to become your biggest shareholder and a member of your board,” Steve tells him. “And I think I owe you the right, given this knowledge, to back out of the deal.”

Iger chooses to go through with it. As it turns out, the acquisition is a brilliant move, quickly re-establishing Disney at the cutting edge of animation. By keeping his ego in check and realizing that he wasn’t the guy who was going to rebuild Disney’s animation studio, Iger was able to make a big bet that paid off phenomenally well. (Sadly, Steve passed away five years later, in 2011.)

Another big bet that Iger made was to build a streaming service that would host all of Disney’s content. It may seem obvious now, but at the time Iger made the decision, it was considered a risky move. Disney would have to take their content off other services, where it was generating healthy revenue streams for the company. Would they be cannibalizing their other business, like the ABC television network? Could they attract enough subscribers to make it worthwhile?

Iger knew that, to draw enough of an audience, Disney would need a massive amount of great content. That is why he was willing to potentially overpay not only for Pixar but also for Lucasfilm, Marvel, and the non-news divisions of 21st Century Fox. As Iger makes clear in the book, his strategy was to double down on high-quality content and put it into a modern format via a streaming service. I think it is fair to say the strategy worked: Disney+ gained more than 28 million subscribers in its first three months.

Iger concludes the book with a list of what he calls “lessons to lead by.” Normally, I am allergic to lists like this because they’re so vacuous. But Iger’s is quite perceptive. For example, he advises, “Value ability more than experience, and put people in roles that require more of them than they know they have in them.” And he writes, “I became comfortable with failure—not with lack of effort, but with the fact that if you want innovation, you need to grant permission to fail.” Melinda and I regularly give the same advice to the teams at our foundation.

Earlier this year, Iger stepped down as CEO of Disney after 15 years and announced that he plans to retire from the company in 2021. He has had a brilliant career. I think anyone would enjoy this book, whether they’re looking for business insights or just want a good read by a humble guy who rose up the corporate ladder to successfully run one of the biggest companies in the world.

Why ask why?

Not everything happens for a reason

A wise and funny memoir from a young woman facing her own mortality.

I spend my days asking “Why?” Why do people get stuck in poverty? Why do mosquitoes spread malaria? Being curious and trying to explain the world around us is part of what makes life interesting. It’s also good for the world—scientific discoveries happen because someone insisted on solving some mystery. And it’s human nature, as anyone who’s fielded an endless series of questions from an inquisitive 5-year-old can tell you.

But as Kate Bowler shows in her wonderful new memoir, Everything Happens for a Reason and Other Lies I’ve Loved, some “why” questions can’t be answered satisfactorily with facts. Bowler was 35 years old, married to her high-school sweetheart, and raising their young son when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. When she got sick, she didn’t want to know what was making her body’s cells mutate and multiply out of control. She had deeper questions: Why me? Is this a test of my character?

The book is about her search for answers that align with her deeply held religious beliefs. A professor at Duke Divinity School in North Carolina, she grew up in a family of Mennonites and wrote a history of the prosperity gospel, the idea popular among some Christians that God rewards the faithful with health and wealth. Before she got sick, Bowler didn’t subscribe to the prosperity gospel, but she didn’t exactly reject it either. “I had my own prosperity gospel, a flowering weed grown in with all the rest,” she writes. “I believed God would make a way.” Then came her diagnosis. “I don’t believe that anymore.”

Given the topic, I wasn’t surprised to find that Bowler’s book is heartbreaking at times. But I didn’t expect it to be funny too. Sometimes it’s both in the same passage. In one scene, Bowler learns there’s a 3 percent chance that her cancer might be susceptible to an experimental treatment. A few weeks later, her doctor’s office calls with good news: She’s among the 3 percent. “I start to yell. I have the magic cancer! I have the magic cancer!” She turns to her husband: “ ‘I might have a chance,’ I manage to say between sobs…. He hugs me tightly, resting his chin on my head. And then he releases me to let me sing ‘Eye of the Tiger’ and do a lot of punching the air, because it is in my nature to do so.”

The central questions in this book really resonated with me. On one hand, it’s nihilistic to think that every outcome is simply random. I have to believe that the world is better when we act morally, and that people who do good things deserve a somewhat better fate on average than those who don’t.

But if you take it to extremes, that cause-and-effect view can be hurtful. Bowler recounts some of the unintentionally painful things that well-meaning people told her, like: “This is a test and it will make you stronger.” I have also seen how this line of thinking affected members of my own extended family. All four of my grandparents were deeply devout members of a Christian sect who believed that if you got sick, it must be because you did something to deserve it. When one of my grandfathers became seriously ill, he struggled to figure out what he might have done wrong. He couldn’t think of anything, so he blamed his wife. He died thinking she had caused his illness by committing some unknown sin.

Bowler answers the “why” question in a compelling way: by refusing to accept the premise. As the title suggests, she rejects the idea that we need a reason for everything that happens. But she also rejects the nihilist alternative. As she said in one TV interview: “If I could pick one thing, it would be that everyone simmers down on the explanations for other people’s suffering, and just steps in with love.” She even includes an appendix with six ways you can support a friend or loved one who’s sick. It’s worth dog-earing for future reference.

Everything Happens belongs on the shelf alongside other terrific books about this difficult subject, like Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air and Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal. Bowler’s writing is direct and unsentimental. She's not saying her life is unfair or that she deserved better. She’s just telling you what happened.

I won’t spoil the ending, except to say that Bowler has too much integrity as a writer to offer pat answers or magic solutions. When I was done with the book, I went online to see how she was doing. I was happy to find that she was still keeping a blog about faith, morality, and mortality. It’s inspiring to see this thoughtful woman face such weighty topics with honesty and humor.

Trans Atlantic humor

Eddie Izzard is a comic genius

And his memoir is terrific—as long as you’ve seen his act.

I’ve recently discovered that I have a lot in common with a funny, dyslexic, transgender actor, comedian, escape artist, unicyclist, ultra-marathoner, and pilot from Great Britain. Except all of the above.

Eddie Izzard is one of my favorite performers. Melinda and I had the pleasure of seeing one of his comedy shows live in London, and then we got to talk with him backstage after the show. So I was excited to pick up his autobiography, Believe Me. It was there that I learned for the first time that Izzard and I share a lot of the same strengths and weaknesses.

As a child, Eddie was nerdy, awkward, and incompetent at flirting with girls. He had terrible handwriting. He was good at math. He was highly motivated to learn everything he could about subjects that interested him. He left college at age 19 to pursue his professional dreams. He had a loving mom who died of cancer way too young.

I can relate to every one of these things.

You might find you share similarities with Eddie as well. In fact, that’s the overarching point of this book. We’re all cut from the same cloth. In his words, “We are all totally different, but we are all exactly the same.”

If you’ve never seen Eddie perform his stand-up routine, you’re missing out. Like Monty Python, he often draws from real historical figures, such as Shakespeare or Charlemagne, and comes up with hilarious riffs, many of them improvised. And like other super talented comedians like Robin Williams and Tom Hanks, he’s also great in serious dramatic roles. (He recently appeared in the movie Victoria and Abdul, with Dame Judi Dench.) He even talks semi-seriously about running for Parliament.

Despite all those gifts, I’m not sure I’d recommend this book for those who’ve never seen Eddie perform. There are some comedians, such as David Sedaris and George Carlin, whose books would make perfect sense even if you haven’t seen their act. That’s not the case here. You have to witness his brand of surreal, intellectual, self-deprecating humor. Otherwise, it will be like you’re walking into the middle of a conversation.

But if you have seen Eddie’s stuff and you like it—here’s a typical bit, a riff on Pavlov’s dogs—I promise you’ll love this book. You’ll see that his written voice is very similar to his stage voice. You’ll also see that the book provides not just laugh-out-loud moments but also a lot of touching insights into how little Edward Izzard, a kid with only a hint of performing talent, became an international star.

The book begins with the event that had by far the biggest impact on his life—the death of his mom in 1968, when Eddie was just six years old. Eddie’s father, an accountant who traveled a lot for work, was not able to care for Eddie and his brother by himself. So the Izzard boys were sent off to a boarding school near a Welsh seaside resort “where you’d expect a few dead bodies to wash up occasionally … but no such luck.” Imagine you’re six years old, you’ve just lost your mom, you’re starting to have gender-identity issues that make no sense to you, and you’re packed away to a boarding school where you have to cry yourself to sleep!

As hard as these experiences were, there’s no way Eddie would be the star he is today if they hadn’t happened. “I do believe I started performing and doing all sorts of big, crazy, ambitious things because … on some childlike magical-thinking level, I thought doing those things might bring her back. But she never came back. I keep trying, though, just in case.”

He’s honest about the fact that he was the opposite of a natural. Instead of innate talent, he had something perhaps more important: a burning desire to be in show business and the propensity to be relentless in pursuit of his goals.

He spent most of the 1980s working as a street performer, often in London’s Covent Garden. It was a slog, with a lot of embarrassing moments. But he got much better the old-fashioned way: by working at it day in and day out and learning from his many failures.

In fact, I couldn’t help but think that Eddie’s life would be a perfect case study for the Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, who has written about the concept of the “growth mindset.” As Dweck explains in her book Mindset, the growth mindset is one in which you believe that your capabilities derive from practice and perseverance rather than DNA and destiny.

Eddie has the growth mindset in spades. Being lousy at something doesn’t stop him from doing it. In fact, it often has the opposite effect, driving him to work at it until he is no longer terrified of it.

Not only did he apply that to performing in front of huge audiences, despite his fundamental shyness. That growth mindset also drove him to become a pilot, despite his fear of heights. It drove him to run 27 marathons in 27 days, despite his lack of natural athleticism. And it drove him to start performing stand-up in French, German, Arabic, Russian, and Spanish, despite the difficulty of learning these languages and translating his British humor into other cultural contexts.

Maybe most difficult of all, that growth mindset allowed him to walk out the door of his home in 1985 in makeup and a dress, despite opening himself up to ridicule and hate. But doing so was liberating: “It led to … a world I could begin to change in my own personal way, carving out for myself a small slice of freedom of expression.”

I’m always impressed by the growth mindset when I see it in action. Now that I understand how much it’s at the core of Eddie’s brilliance on stage, I’ve become an even more devoted fan of his.

Making his mark

Satya Nadella’s guide to the future

When the Microsoft CEO asked me to write the foreword for his new book Hit Refresh, I was happy to say yes.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the future. When I’m deciding which book to read next, I often reach for ones that offer another perspective on where society is headed. So when Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella told me that he was working on a new book about the future of technology, I couldn’t wait to read it. And when he asked me to write an introduction for Hit Refresh, I was happy to say yes.

I hope you’ll enjoy my foreword, which I’ve shared below. Satya has a lot of interesting things to say about the transformation of both Microsoft and the tech industry at large. I’ve benefitted from his insights for decades, and I’m glad everyone else will now have the same opportunity to learn from him.

Foreword:

I’ve known Satya Nadella for more than twenty years. I got to know him in the mid-nineties, when I was CEO of Microsoft and he was working on our server software, which was just taking off at the time. We took a long-term approach to building the business, which had two benefits: It gave the company another growth engine, and it fostered many of the new leaders who run Microsoft today, including Satya.

Later I worked really intensely with him when he moved over to run our efforts to build a world-class search engine. We had fallen behind Google, and our original search team had moved on. Satya was part of the group that came in to turn things around. He was humble, forward-looking, and pragmatic. He raised smart questions about our strategy. And he worked well with the hardcore engineers.

So it was no surprise to me that once Satya became Microsoft’s CEO, he immediately put his mark on the company. As the title of this book implies, he didn’t completely break with the past—when you hit refresh on your browser, some of what’s on the page stays the same. But under Satya’s leadership, Microsoft has been able to transition away from a purely Windows-centric approach. He led the adoption of a bold new mission for the company. He is part of a constant conversation, reaching out to customers, top researchers, and executives. And, most crucially, he is making big bets on a few key technologies, like artificial intelligence and cloud computing, where Microsoft will differentiate itself.

It is a smart approach not just for Microsoft, but for any company that wants to succeed in the digital age. The computing industry has never been more complex. Today lots of big companies besides Microsoft are doing innovative work—Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and others. There are cutting-edge users all around the world, not just in the United States. The PC is no longer the only computing device, or even the main one, that most users interact with.

Despite all this rapid change in the computing industry, we are still at the beginning of the digital revolution. Take artificial intelligence (AI) as an example. Think of all the time we spend manually organizing and performing mundane activities, from scheduling meetings to paying the bills. In the future, an AI agent will know that you are at work and have ten minutes free, and then help you accomplish something that is high on your to-do list. AI is on the verge of making our lives more productive and creative.

Innovation will improve many other areas of life too. It’s the biggest piece of my work with the Gates Foundation, which is focused on reducing the world’s worst inequities. Digital tracking tools and genetic sequencing are helping us get achingly close to eradicating polio, which would be just the second human disease ever wiped out. In Kenya, Tanzania, and other countries, digital money is letting low-income users save, borrow, and transfer funds like never before. In classrooms across the United States, personalized-learning software allows students to move at their own pace and zero in on the skills they most need to improve.

Of course, with every new technology, there are challenges. How do we help people whose jobs are replaced by AI agents and robots? Will users trust their AI agent with all their information? If an agent could advise you on your work style, would you want it to?

That is what makes books like Hit Refresh so valuable. Satya has charted a course for making the most of the opportunities created by technology while also facing up to the hard questions. And he offers his own fascinating personal story, more literary quotations than you might expect, and even a few lessons from his beloved game of cricket.

We should all be optimistic about what’s to come. The world is getting better, and progress is coming faster than ever. This book is a thoughtful guide to an exciting, challenging future.

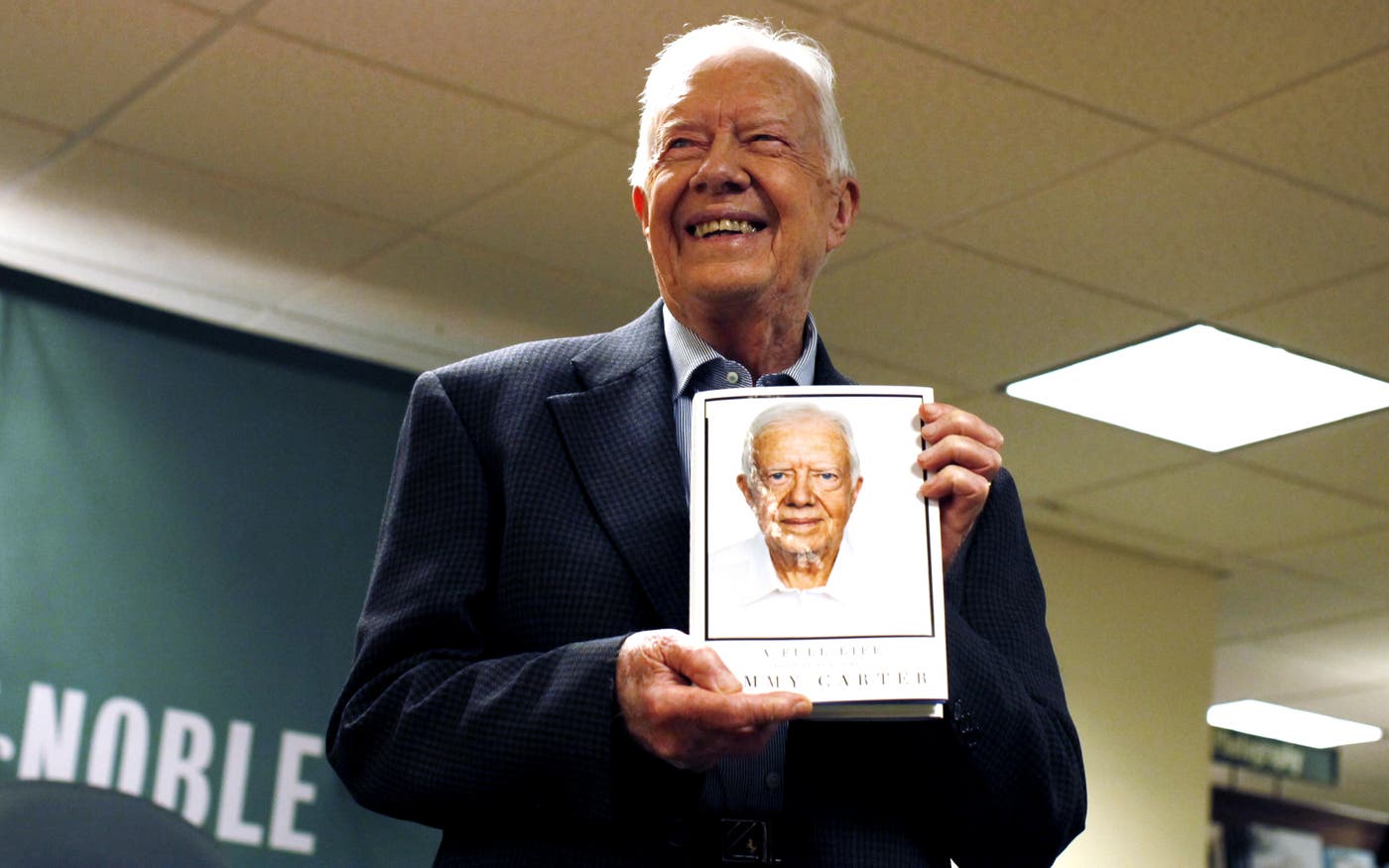

Good book, great man

Jimmy Carter’s full life

A quick retelling of the former president’s fascinating story.

Last week, Jimmy Carter made a surprise appearance at our foundation’s annual employee meeting. His visit was a huge honor for all of us. I think he was an even bigger hit with our colleagues than Bono, who stopped by a few years ago. They particularly loved hearing him talk about Rosalynn, his wife of over 70 years. According to the former President, the secret to their incredible love story is simple: give each other space, and never go to bed angry. Our team soaked up all the insights he had to offer on love, global health, and many other topics.

For years our foundation has worked closely with the Carter Center in the fight against Guinea worm disease, onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis, and many other diseases. Melinda and I recently had a chance to spend an evening with Jimmy and Rosalynn at their home, in Plains, Georgia. At age 92, and after a scary battle with malignant melanoma, President Carter is as sharp as ever. Mrs. Carter, who is also super smart, is still her husband’s closest friend and advisor.

In preparation for our trip to Plains, I read President Carter’s newest book, A Full Life. The book would have been a worthwhile read under any circumstances. At less than 250 pages, it’s a quick, condensed tour of Carter’s fascinating life. His storytelling is simple and elegant, just like the wood furniture Carter has made by hand all his life.

Although most of the stories come from previous decades, A Full Life feels timely in an era when the public’s confidence in national political figures and institutions is low. It is true that President Carter made unforced errors during his time in office. But when you read this book and have a chance to meet him in person, you can’t help but conclude that Carter is a brave, thoughtful, disciplined leader who understands the world at a remarkable level and who has improved the lives of billions of people through his advocacy for human rights and global health.

I loved reading about Carter’s improbable rise to the world’s highest office. He spent his early years in rural Georgia, in a small Sears Roebuck house without running water, electricity, or insulation. His highest aspiration was to become a plowman on his family’s farm.

His first exposure to the wider world came through his service in the U.S. Navy. He earned a student appointment at the U.S. Naval Academy during World War II, served as an officer on submarines during the Korean War, and went on to develop advanced nuclear subs. Despite being on a fast track in the Navy, Carter decided to return home to Georgia to run the family farm after his father’s passing—a move that made Rosalynn furious.

In retrospect, it makes sense that Carter would want to follow in his dad’s footsteps. James Earl Carter was a strict man who rarely gave his son praise, but Jimmy revered him. This close father-son relationship shaped Jimmy’s whole life.

To earn his father’s approval, Jimmy became a Jack of all trades and a master of most. He became skilled at everything from farming to forestry, firefighting to furniture making, differential calculus to nuclear physics. (Being a master of so many things can also have a downside. As president, he was often criticized for micromanaging, to the point of wanting to oversee the schedule for the White House tennis court.)

Perhaps more than anything else, James modeled for his son a commitment to service. While running his farm and doing significant manual labor himself, James served in the Georgia legislature, on the local board of education, on the local hospital authority, and in many other volunteer posts. These civic values are what led the younger Carter to run for the Georgia Senate in 1962. He’s lucky he had Rosalynn by his side in that race. She had great political instincts and helped him rise all the way to the White House over the subsequent 14 years.

Even though Carter had already written more than two dozen books before this one, he somehow managed to save some great anecdotes for this book. I’ll share two of my favorites:

Carter salvaged the Camp David Accords with a small human gesture. Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin was furious with Carter, and the negotiations were just about to get called off, when Carter went to Begin’s cabin and gave him photographs with personal inscriptions for each of Begin’s eight grandchildren. After reading the notes, Begin “had a choked voice, and tears were running down his cheeks. I was also emotional, and he asked me to have a seat. After a few minutes, we agreed to try once more.” The rest, as they say, is history.

During the Iran Hostage Crisis, the CIA managed to sneak agents into Tehran with false German passports. One agent was caught by customs officials. “Something is wrong with your passport,” the official said. “This is the first time I’ve seen a German document that used a middle initial instead of a full name. Your name is given as Josef H. Schmidt.” The agent saved his skin with a brilliant response: “Well, when I was born my given middle name was Hitler, and I have received special permission not to use it.”

A Full Life is a good read about a great man. It made me think of David Brooks’s book The Road to Character and its insights about the values that give life purpose. As Brooks explains, the Book of Genesis contains two very different versions of Adam. “Adam I is the career-oriented, ambitious side of our nature,” Brooks writes. “He wants to have high status and win victories.” Adam II, in contrast, “wants to have a serene inner character, a quiet but solid sense of right and wrong—not only to do good, but to be good.” Jimmy Carter brought Adam II to the fore.

Sole Man

An honest tale of what it takes to succeed in business

Phil Knight opens up in a way few CEOs do in his candid memoir about creating the Nike shoe empire.

Many books I’ve read about entrepreneurs follow a common, and I believe misleading, storyline. It goes like this: A sharp entrepreneur gets a world-changing idea, develops a clear business strategy, recruits a crack team of partners, and together they rocket to fame and riches. Reading these accounts, I’m always struck by how they make their achievements appear to be the inevitable result of some great prescience or unusual skill. It’s no wonder publishers churn out “how-to” titles packed with tidy checklists, 5-step programs, and other simplistic recipes for entrepreneurial success.

Shoe Dog, Phil Knight’s memoir about creating Nike, is a refreshingly honest reminder of what the path to business success really looks like. It’s a messy, perilous, and chaotic journey riddled with mistakes, endless struggles, and sacrifice. In fact, the only thing that seems inevitable in page after page of Knight’s story is that his company will end in failure.

Failure, of course, is about the last thing people would associate with Nike today. The company’s sales top $30 billion and Nike’s swoosh is one of the most universally recognized logos across the globe. Walk down almost any street in the world and you’ll likely find someone wearing a pair of Nikes. But Knight brings readers back more than 50 years to the incredibly humble and fragile beginnings of the company when he started selling imported Japanese athletic footwear out of the back of his Plymouth Valiant.

I’ve met Knight a few times over the years. He’s super nice, but also very quiet. Like many other people who’ve met him, I found him difficult to get to know. As famous as his company has become, Knight was a mystery among Fortune 500 executives.

In the pages of Shoe Dog, however, Knight opens up in a way few CEOs are willing to do. He’s incredibly tough on himself and his failings. He doesn’t fit the mold of the bold, dashing entrepreneur. He’s shy, introverted, and often insecure. He’s given to nervous ticks—snapping rubber bands on his wrist and hugging himself when stressed in business negotiations. It took him weeks to tell Penny, the woman who would become his wife, that he liked her. And yet, in spite of or perhaps because of his unusual character traits, he was able to realize the “Crazy Idea,” as he calls it, to do something different with his life and create his own shoe company.

Knight’s interest in shoes started at the University of Oregon, where he ran track for legendary running coach Bill Bowerman. He then went to Stanford for his MBA, where he wrote a paper about the potential market for importing Japanese athletic shoes to the U.S. At the time, Japanese cameras were making a dent in the German-dominated camera market. Why not do the same with Japanese running shoes which he thought could compete against leading German athletic shoe makers Adidas and Puma?

So far, this storyline may feel familiar. It’s the myth of the young entrepreneur with a world-changing idea who is headed down a straight path to success. But the rest of Knight’s journey rips that myth to shreds.

Much of the suspense in the book is built by the precarious nature of Knight’s finances. He started his shoe import business, known then as Blue Ribbon Sports, with $50 from his father. It was the beginning of many years of living in debt. Year after year, he goes on his knees to his bankers to beg for more credit so he could import more Japanese shoes. He rarely had any savings in the bank because he would plow all of his profits back into the company to order more shoes from Japan. Even as sales of his shoes took off, his business was constantly on life support. Meanwhile, he had a rocky relationship with his Japanese shoe supplier, whose executives were constantly eyeing other potential U.S. partners, despite Knight’s success selling and helping to improve the designs of their shoes. Eventually, Knight broke away and started Nike, beginning another round of uncertainty.

Knight is amazingly honest about the accidental nature of his company’s success. Consider the famous Nike swoosh. He paid an art student $35 to design it, but he didn’t recognize what a special logo it would become. “It’ll have to do,” he said at the time. The decision to call the company Nike was also not Knight’s top choice. He wanted to name it Dimension Six, but his employees pushed him to choose Nike. At the time, Knight agreed but he was not convinced. “Maybe it will grow on us,” he said.

When I was starting Microsoft I was fortunate enough that I was entering a business that didn’t have such tight margins. I didn’t struggle with banks to get financing as Knight did. I also didn’t need to struggle with the large factories, which I wish Knight spent more time explaining. After reading close to 400 pages about the shoe business, I was disappointed that I didn’t learn more about what it takes to manufacture an athletic shoe: what are all the parts of the shoe? which ones are difficult to manufacture and why?

What I identified most with from his story were the odd mix of employees Knight pulled together to help him start his company. Among them, a former track star paralyzed after a boating accident, an overweight accountant, and a salesman who obsessively wrote letters to Knight (to which Knight never responded). They were not the people you would expect to represent a sportswear company. It reminded me of my very early days at Microsoft. Like Knight, we pulled together a group of people with weird sets of skills. They were problem solvers and people who shared a common passion to make the company a success. We all worked hard, but it was also lots and lots of fun.

Readers looking for a lesson from Knight’s book may leave this book disappointed. I don’t think Knight sets out to teach the reader anything. There are no tips or checklists. Instead, Knight accomplishes something better. He tells his story as honestly as he can. It’s an amazing tale. It’s real. And you’ll understand in the final pages why, despite all of the hardships he experienced along the way, Knight says, “God, how I wish I could relive the whole thing.”

Infinite Genius

A literary master serves up a winner

I loved this book on tennis as much for the writing as its insights into my favorite sport.

When it comes to books, it’s pretty rare that I get intimidated. I read all kinds of books, including ones that only the harshest college professors would assign. And yet I must admit that for many years I steered clear of anything by David Foster Wallace. I often heard super literate friends talking in glowing terms about his books and essays. I even put a copy of his tour de force Infinite Jest on my nightstand at one point, but I just never got around to reading it.

I’m happy to report that has now changed. It started last year when I watched “The End of the Tour,” a great movie with Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg that takes place when Wallace was on the road somewhat reluctantly promoting Infinite Jest. The movie made Wallace seem so damn interesting, and it really humanized him for me. In addition to shedding light on the nature of his literary genius, it also foreshadows the depression that led him to commit suicide in 2008. Recently, I also watched an amazing video of Wallace’s famous 2005 commencement speech at Kenyon College. It is one of the most moving speeches I’ve heard in a long time.