Lamb. Jackson Lamb.

I binge-watched this great British spy series

Slow Horses stars Gary Oldman as the anti-James Bond.

I’m a huge fan of spy movies and shows. Although I like James Bond just fine, I really go for the characters who rely on their brains, aren’t especially good in a fistfight, and don’t fill out a tuxedo too well.

Jackson Lamb, the lead character in the Apple TV+ series Slow Horses, is an extreme version of one of those spies. He rarely bathes. His shirt is always covered with crumbs, and he wears a stained trench coat that hasn’t been washed in years. He’s a smoker and an alcoholic. He has a terrible temper and is nasty to his subordinates. He doesn’t even attempt to hide his flatulence. If you asked an AI to invent the opposite of James Bond, it would give you Jackson Lamb.

But Lamb has one thing in common with 007: He is really good at his job. Played by Gary Oldman, he’s the head of Slough House, a fictional group inside the British intelligence agency that people get sent to when they mess up badly, but not quite badly enough to get fired. It’s a bureaucratic dumping ground where the agents aren’t expected to do any real work—they’re just biding their time until they can get reassigned. Slow Horses gets its title from the derisive nickname that the rest of British intelligence uses for Slough House agents.

The show reminds me of John le Carré novels, which have lots of complex characters and complicated plots. (In fact, Slow Horses is based on a series of novels by British novelist Mick Herron.) Lamb clearly resents getting stuck with this dead-end job—you eventually find out how he ended up there—but he’s incredibly capable and takes his work seriously. Just when it seems like things can’t turn out well, you find out that he has outsmarted everybody. And he manages to get the best out of his people in a tough love kind of way.

One of Lamb’s key agents is River Cartwright, who’s assigned to Slough House after taking the blame for a big foul-up in the show’s opening scene. River makes a lot of mistakes, often with serious consequences, but he’s a good agent and you’re always rooting for him. His grandfather was a legendary intelligence agent, and River struggles to live up to his expectations.

The other characters are well fleshed out too—well enough that when one of the agents is killed, you really feel it. (At least I did!) You also meet some powerful and fascinating people at the main office who plot and scheme against each other to gain power. Kristin Scott Thomas is especially good as Lamb’s clever boss, Diana Taverner.

Although I don’t know anything about the world of spies, most of the spycraft seems pretty believable—there are no tricked-out Aston Martins in this show. Still, I had to laugh at the way Slough House’s computer expert can hack into any device anywhere in record time. It moves the plot along, but it’s hard to believe.

Whenever I’m talking with someone about great spy movies, I always mention two that both happen to star Robert Redford: Three Days of the Condor, which was a hit in 1975, and a hidden gem called Spy Game, which came out in 2001. Now I’m going to add Slow Horses. It’s up there with the best spy stuff I’ve seen.

Production diary

Behind the scenes of my new Netflix series

I had a lot of fun filming What’s Next?, which you can watch now.

I've always thought of myself as a student trying to get to the bottom of things. A good day for me is one where I go to sleep with just a little bit more knowledge than I had when I woke up in the morning. So, when I am deciding how to spend my time these days, I usually ask myself three questions: Will I have fun? Will I make a difference? And will I learn something?

My new Netflix Series, What’s Next? The Future with Bill Gates, is out today. And when I think back on the process of working on it over the last two years, the answer to all three questions is a resounding “yes.”

I had an amazing time working with the super talented director, Morgan Neville. Morgan directed one my favorite documentaries, Best of Enemies, which is about Gore Vidal’s and William Buckley’s debates during the 1968 U.S. presidential election. Morgan also won an Oscar for his terrific film 20 Feet from Stardom.

As you might guess from the title, What’s Next? is a show about the future. I’m very fortunate to get to work on a number of interesting problems. Between fighting to reduce inequities through the Gates Foundation, leading Breakthrough Energy’s work on the climate crisis, and my continued engagement with Microsoft, I have a front seat to some of the biggest challenges facing us today.

I feel extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to work with and learn from some truly incredible people during the making of this show. (I’m hesitant to even use the word “work” because the process was so much fun!) My hope is that people watch What’s Next? and feel like they’re joining me on my learning journey.

Each episode focuses on a different challenge: artificial intelligence, climate change, misinformation, disease eradication, and income inequality. I sat down with some of the big thinkers and innovators who are pushing for progress. Some of them have different ideas than I do about how to tackle these challenges, and I loved getting to hear their perspectives. It was an eye-opening experience.

I got to have conversations on camera with familiar faces like Dr. Anthony Fauci, Open A.I. co-founder Greg Brockman, and the groundbreaking director James Cameron. And I made a lot of new friends as well—including an ingenious malaria researcher from Burkina Faso named Abdoulaye Diabaté, young climate activists who impressed me with their intelligence and passion, and an amazing group of people from across the Bay Area who overcame tremendous adversity in their path from poverty to stability.

There also were dozens of people who participated in the series with standalone interviews, like my friend Bono and the brilliant Mark Cuban—each of whom brings an inspiring and grounded view of the challenges we’re facing. My hope is that, together, we can combat the doomsday narratives that so often surround these issues.

It’s hard to pick which discussion I learned the most from. But three conversations will always stand out in my memory: the ones with Lady Gaga, Senator Bernie Sanders, and my younger daughter, Phoebe.

Going Gaga

I couldn’t help but feel a little nervous.

I was in Palm Desert, CA, preparing to have a filmed conversation with Lady Gaga for our episode about misinformation. Being around famous people doesn’t normally affect me. But I’m a big fan of A Star is Born—especially its music—and I was aware of her reputation as an outsized personality. I couldn’t wait to hear what she had to say.

Luckily, I had nothing to worry about. I was blown away by how thoughtful Gaga was. She made me laugh with the outrageous stories of how she’s been the subject of misinformation in the past—and inspired me with some of the ways she thinks about the topic.

In the early years of her career, one of the most persistent internet rumors about Gaga was that she was actually a man. It became so mainstream that reporters would ask about it during interviews. She refused to confirm or deny it. Instead, Gaga turned it back on the interviewer and asked, “Would it matter if I was?”

On the day of our Netflix conversation, I had been filming earlier with my two sisters, Kristi and Libby. So I asked them to come and watch the conversation between Lady Gaga and me.

Mistle-tones

My holiday Spotify playlist

The soundtrack to my season is snow joke.

When I think of the holidays, two things always come to mind: matching pajama sets—a tradition in my family—and, of course, holiday music. As soon as Thanksgiving is near, I switch up my soundtrack to something festive, cheerful, and seasonally appropriate.

This Spotify playlist is a collection of tracks that help me get into the holiday spirit. It’s a mix of my favorite classics (and some more modern tunes) from around the world. Whether you listen in an ugly sweater, while wrapping presents, or around the table with family and friends, I hope these songs bring as much joy to your holidays as they do to mine.

Happy holidays, and happy listening!

Econo-mix

The economics of binge-watching

I love these online courses by Timothy Taylor on the real-world applications of an abstract subject.

I love taking online courses. With just a few hours of dedicated watching, I’ve been able to dive deep into topics as varied as the science of language, the human body, glassmaking, particle physics, the weather, classical mathematics, birdwatching, and the history of everything. Before there were streaming platforms like Wondrium (also known as the Great Courses), which offers on-demand access to some of the best courses out there, I sometimes gave the DVD sets of my favorites as holiday gifts.

Three of those favorites are economics courses by Timothy Taylor, who is one of my all-time favorite professors. I watched all of them over a decade ago; even so, when one of my kids recently asked me to recommend a book on economics, Taylor’s video lectures were the first thing I thought of.

The simply titled Economics, 3rd Edition is Taylor’s most straightforward offering. Divided into 36 episodes (lectures), this online course is one of the best primers out there on the fundamentals of the field—covering concepts and topics like price floors and ceilings, the division of labor, supply and demand, public goods, banking, international trade, inequality, regulation, and more. Whether you’ve never taken an economics class before, or you majored in the subject and graduated with honors, I’m confident that Taylor’s approach to these not-so-basic ideas will still teach you something.

The next course is Taylor’s America and the New Global Economy. It’s a fantastic introduction to macroeconomics that charts 50 years of global economic history to explain how each region of the world developed and changed over time. I found Taylor’s region-by-region analysis incredibly valuable, especially when he discusses the impact of certain government policies like investing in education and infrastructure. The course was released over 15 years ago, and I wish it were updated to cover the 2008 financial crisis and everything that’s happened since.

One of Taylor’s strengths as a teacher is his knack for presenting complex, often misunderstood ideas in a way that's both enlightening and accessible. This is no small feat when tackling the expansive and frequently abstract world of economics, but Taylor makes it seem easy. And nowhere is this strength more apparent than in the third course of his, Unexpected Economics—a series of 24 lectures on topics that most of us wouldn’t connect to his area of expertise. If you liked Freakonomics, you’ll probably like Unexpected Economics too.

Unexpected Economics starts with “The World of Choices,” a compelling opening lecture that reframes economics as the science of decision-making in every aspect of life. It’s an invitation to view our daily actions through an economic lens, and to consider the hidden costs and benefits that accompany every choice we make.

Given that the holidays are just around the corner, I also recommend the lecture called “Altruism, Charity, and Gifts.” Taylor’s investigation into the nature of giving concludes with him sharing what kinds of gifts are most valuable to their recipients. It was fitting to be reminded of “the deadweight loss of Christmas”—a term that economist Joel Waldfogel coined to describe his finding that the average Christmas gift is worth 15 percent less to its recipient than what its giver paid for it.

Another of the course's standout lectures, “Traffic Congestion – Costs, Pricing, and You,” turns an everyday annoyance into a lesson on the “tragedy of the commons.” As someone who loves driving and hates being stuck in a long, unmoving line of cars, it was a good reminder: All of us prefer to think of ourselves as victims of traffic, but in reality, we’re also causes of it. The lecture’s exploration of London's congestion pricing, soon to be implemented in New York City, is a testament to how economics can inform public policy solutions—and the consequences and negative externalities that arise when economics aren’t considered.

That’s a recurring theme throughout the course. In “The Economics of Natural Disasters,” Taylor explains that although natural disasters are events within nature, their effect on people “is a matter of trends and policies that have a strong economic component.” That’s why two earthquakes with the exact same magnitude on the Richter scale can have radically different outcomes depending on how many people were exposed to one versus the other—and, crucially, on the vulnerability of each exposed population. What happens beneath the earth’s surface might not be a matter of economics, but where a city is developed, how big its population is, and whether or not people live clustered together in less-stable, unregulated structures or spread out in reinforced buildings that abide by strict codes… All of that is economics.

I mentioned that I wish Taylor’s America and the New Global Economy had been updated, and I feel the same about Unexpected Economics. A lot has happened in the world since this series was recorded in 2011, and I can’t help thinking about how useful Taylor’s perspective—which uses economics to explain human behavior, health, politics, sports, prediction markets, and even parenthood—would be today.

At the same time, I was struck by the enduring relevance of the content. For example, in the lecture on natural disasters, Taylor notes that news outlets tend to disproportionately cover the ones that look scary—but not necessarily the ones that are most lethal. He quotes a fascinating study that found that for every person who dies in an earthquake, more than 19,000 must die of food shortages to receive the same expected media coverage. I’ve seen something similar when it comes to climate change: The headlines often fail to reflect the trendlines.

Long after I first watched all three of his lectures, Taylor’s work still feels fresh and urgent. More than a course on a single subject, Unexpected Economics, America and the New Global Economy, and Economics, 3rd Edition are all masterclasses in how to look at the world—and how to understand the invisible forces shaping our lives. And even if Taylor doesn’t directly apply his wisdom to the issues we face in 2023, he provides enough of a foundation for us to connect the dots and do it ourselves.

Sound advice

My summer Spotify playlist

Not bad for a granddad.

I can’t imagine my life without music. Some of my fondest childhood memories took place in Paul Allen’s basement, where he’d turn on the record player and turn me on to artists like Jimi Hendrix and albums like Are You Experienced? And like a lot of people, when I got older, I discovered the joys of listening to a great song while going for a drive. These days, I love learning about new songs and artists through recommendations from my kids, who have great ears, and friends like Bono (whose ear isn’t too shabby, either).

This Spotify playlist includes many of my favorites—songs newer and older that have stuck with me over the years. Whether you're hosting a backyard BBQ, sitting on the beach, or just driving around with the windows down, feel free to make it part of the soundtrack to your summer, too.

Happy listening!

A great Dane

This political drama from Denmark stands out

Borgen has a lot to say about coalitions and the people who form them.

I’m fascinated by coalitions: how difficult they are to build, how complicated they are to maintain, and how easily they can break. I know from experience–in business, climate, health, and education—how necessary they are to creating any sort of change that lasts.

So after watching one episode of the Danish drama Borgen, which follows the journey of the country’s (fictional) first female prime minister and her coalition government, I was hooked. As someone who’s been deeply engaged with global issues and public policy for much of my life, I feel like I can never know enough about what it takes to turn a proposal into a program, to bring a law to life. Before long, I’d binged all four seasons.

Borgen is first and foremost a TV series about politics. The show begins with an unexpected come-from-behind electoral win by Moderate Party leader Birgitte Nyborg. Before she can take a victory lap, though, she has to cobble together other players from parties across the political spectrum to form her government. And even once she does, the process isn’t permanent. With coalitions, it never is. There’s a constant back-and-forth involved in making a majority out of minority stakeholders who agree on some issues and disagree, sometimes vehemently, on others.

America’s two-party system makes us pretty unique. And these days, in American politics, compromise is the exception. But in countries with multiple parties, when none has a clear majority, compromise is the name of the game. In Borgen, politicians with vastly different priorities and agendas on immigration, the economy, and the environment must find a way to work together, always with the shadow of the next election (and the possibility that it might come early) looming. I think Borgen explores that dynamic with nuance, and captures its messiness really well.

For me, the show was certainly educational—but I also appreciated that it wasn’t exactly aspirational. If anything, I’d describe it as excruciatingly realistic. That’s because it portrays the people who make up these alliances and oppositions as, well, people. In and out of power, Nyborg is a principled, charismatic, and talented leader who’s also susceptible to moments of arrogance, ruthlessness, and deeply clouded judgment. Watching the show, you can’t help but root for her. But from early on, you’re also under no illusions that she’s perfect, or anything close to it.

Often forced to choose between what’s politically expedient, what’s right for her country, and what’s right for herself and her family, she fails on all three fronts more than once. Her kids, her friendships, even her relationships pay a huge price. Nyborg is just deeply human, with deeply human struggles that anyone can relate to.

I would say the same thing about the show’s entire cast of characters. Katrine Fønsmark, a budding TV journalist whose character arc I won’t spoil here, is the show’s secondary protagonist-slash-heroine: also principled, also flawed, also doing her best at any given moment—even if the results come up short. She has to cope with tragedy, navigate multiple tricky work situations, and toe the line between right and wrong. Again, you can’t help but empathize with her, mistakes and all.

In the show’s fourth and final season, the writers really pour on the realism. The storyline centers on the discovery of oil in Greenland—something that hasn’t actually happened yet. But the political complexities that arise between Denmark and Greenland and the U.S. and China could have been pulled straight from any newspaper headline. And even so, complicated and lifelike people dealing with everyday issues like illness, aging, and workplace politics are at the heart of it all.

In the end, in a genre often categorized as being either naïve or cynical, Borgen is a political drama that stands out. Rather than villainize, victimize, or deify any of its characters, or any of the situations they find themselves in, the show just makes them feel real. It asks lots of questions—about political compromising, juggling work, the responsibility of media, and what it means to be a good parent—and is uninterested in providing easy answers. Instead, the writers provide some really compelling television and let us come to our own conclusions. I’d highly recommend it to anyone interested in politics, coalition-building, and the triumphs and challenges of leadership.

Lost Time

A powerful look at one family’s hardship and resilience

Time is an emotional, intimate documentary.

I have written before about two books—An American Marriage and The New Jim Crow—that really broadened my understanding of some of the hardships faced by Black people in America. There’s a movie out now called Time that ranks up there with both of them. It was nominated for Best Documentary at the Academy Awards this year, and I can see why. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

I saw Time at the Sundance Film Festival last year (before the COVID-19 pandemic shut things down) on the recommendation of a friend who served as an executive producer on the movie. It is available for streaming now on Amazon Prime; in fact, you can watch it for free this week, even if you don’t have a Prime subscription.

On the surface, Time is about a Black mother of six named Sibil Fox Richardson who is trying to get her husband, Robert, out of state prison in Louisiana. He was sentenced to 60 years for armed robbery; much of the movie takes place at a time when he has been in prison nearly 18 years. Sibil—who also goes by the name Fox Rich—participated in the robbery and served three and a half years herself.

The movie is not about whether Robert and Sibil committed the crime. They did. It is partly about the impact on a family of locking up a father for 60 years—and very much about their family’s resilience.

Many documentaries I’ve seen lay out all the facts in a clear storyline: this happened, then that happened. Time doesn’t work that way. The director, Garrett Bradley, is not interested in explaining every fact. You learn only a few details about the robbery and their separate trials, although there is a long sequence in which Sibil talks about making amends with the victims of their crime.

Although Time doesn’t tell you much, it shows you a lot. It is a poetic portrait of a family who love and support each other despite their difficult circumstances. In one scene, one of the couple’s sons graduates from a dental program. But the movie doesn’t take time to explain what kind of degree he got, or much of anything else. It is all about the joy of his accomplishment and how the family comes together to celebrate. The details are not as important as the way they show up for each other.

The same is true of the movie’s portrayal of Sibil’s efforts to help Robert and speak out more broadly against mass incarceration. She is repeatedly told that there is no news about her husband’s case. There are painfully long scenes of her waiting on the phone to speak to a bureaucrat about a judge’s ruling. It is not always quite clear what the particular ruling in question might be, but again, that is not what matters. The point is how impersonally and inhumanely the system treats everyone caught up in it, including the offenders and their families, and how much time and energy are required to navigate it. This idea is important in American Marriage and New Jim Crow too, but with this movie, you see it first-hand.

If Time wins the Oscar this year, it will be the first documentary directed by a Black woman to do so. Garrett Bradley’s talent makes her worthy of that milestone. This is one of the most intimate movies I have ever seen. It records events that are almost unbearably emotional. There is one scene at the end that is unlike anything I had ever seen before in a documentary. I don’t want to reveal what happens, so I will just say that I could not believe I was watching it. It was that powerful.

COMEDY GOLD

If you want to understand Silicon Valley, watch Silicon Valley

The HBO series gets the tech industry just right.

Considering the huge impact that Silicon Valley has on our lives, I’m surprised by how rarely pop culture really gets it right. I can count the best stuff on one hand. The book Fire in the Valley did a good job of capturing what things were like back in the early years, and the relationship between Steve Jobs and me. (It was turned into a pretty good movie too.) Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve is terrific, and I was blown away by how much history and technical information he synthesized in his book The Innovators. It’s a tour de force.

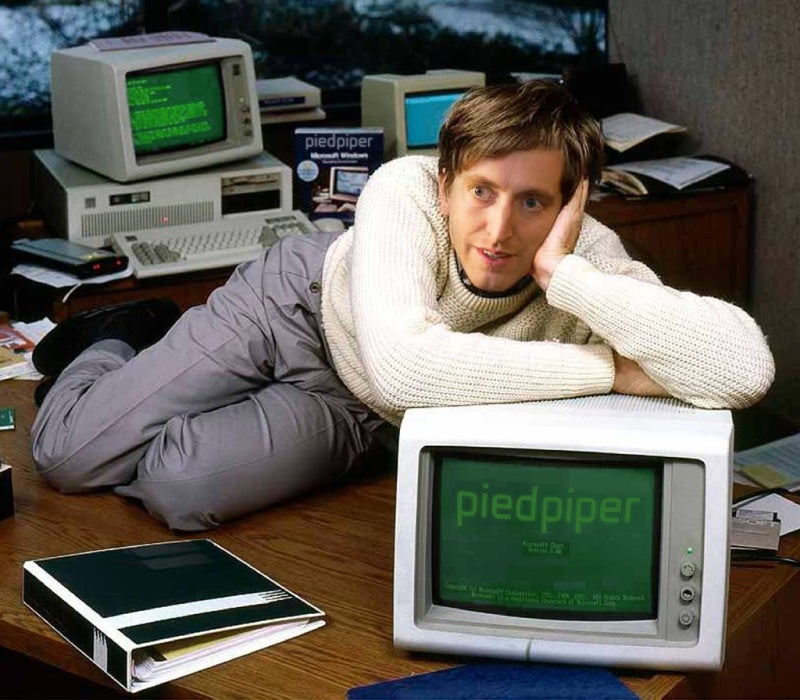

But if you really want to understand how Silicon Valley works today, you should watch the HBO series Silicon Valley.

It’s about a small team of developers at an Internet startup called Pied Piper. You watch them struggle to figure out their strategy, build their product, raise money, and take on Hooli, the tech giant that bears an obvious but superficial resemblance to Google or Microsoft.

The show is a parody, so it exaggerates things, but like all great parodies it captures a lot of truths. Most of the different personality types you see in the show feel very familiar to me. The programmers are smart, super-competitive even with their friends, and a bit clueless when it comes to social cues. Personally, I identify most with Richard, the founder of Pied Piper, who is a great programmer but has to learn some hard lessons about managing people.

And the entrepreneurs are well intentioned but prone to over-the-top vision statements. Even a huge believer in technology like me has to laugh when some character talks about how they’re going to change the world with an app that tells you whether what you’re eating is a hot dog or not.

The accuracy is well-earned. The producers and writers do a lot of research before each new season of the show. Last year I was one of several people they met with to talk about the history of the industry and kick around some of their ideas for season 5. (They didn’t give me any spoilers, though.)

I have friends in Silicon Valley who refuse to watch the show because they think it’s just making fun of them. I always tell them: “You really should watch it, because they don’t make any more fun of us than we deserve.” You can believe, as I do, that tech companies really are improving life with amazing tools and also admit that sometimes, who wins and who loses is pretty arbitrary. Somebody gets an idea almost right, but not quite, and their business fails; then someone else does it just a little bit better and they are viewed as a genius for the rest of their life. The show captures that perfectly.

I do have one minor complaint. Silicon Valley gives you the impression that small companies like Pied Piper are mostly capable while big companies like Hooli are mostly inept. Although I’m obviously biased, my experience is that small companies can be just as inept, and the big ones have the resources to invest in deep research and take a long-term point of view that smaller ones can’t afford. But I also understand why the show focuses so much on Pied Piper and makes Hooli look so goofy. It’s more fun to root for the underdog.

I’ve seen every episode of the first four seasons and am working my way through season 5, which ended in May. I’ve read that the show’s creators originally planned to stop after six seasons, but now they’re open to doing more. I hope they do. I’ll keep watching as long as they keep making this hilarious show.

Documentary now

From the cutting room floor

Read some of the stories that didn’t make the new Netflix docuseries about my life.

Over the last couple of years, I participated in a Netflix series called Inside Bill’s Brain looking at my work and portions of my life. It was fun to spend time with the filmmaker Davis Guggenheim answering questions both serious and silly, and helping him explore my motivations and memories. I hope many people will watch and learn more about the amazing job I’m lucky to have and the people I’m able to meet through this journey Melinda and I find ourselves on as philanthropists. The series is made up of three episodes and is available now on Netflix.

Working on this project gave me a deep regard for how much time and effort goes into crafting a documentary. Filmmakers spend many hours behind the camera to get just a few minutes of the stuff that makes it into the film that viewers see. So much is left on the cutting-room floor. As the project wound down, I decided I’d pick up some of the stories that didn’t make it, ones that I think complement what you’ll see on Netflix. In some cases, the stories I’ll post dive deeper into an issue raised by the documentary. In others, I’ll give the history of why I made an important decision. In all cases, I hope I can show a little bit about myself and the joy I get from trying to help solve the puzzles we face in advancing the human condition.

Speaking up

The day I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life

How giving a speech helped me decide to focus on philanthropy.

Part 1 of the Netflix documentary series Inside Bill’s Brain tells the story of the Gates Foundation’s quest to rethink sanitation for the world’s poorest. First step: reinvent the toilet! This belief in the power of innovation has been a constant in my life, starting from the time I fell in love with software in high school to my work today at our foundation. What follows is the story of a moment of clarity for me on that path and the influence of someone who’s been a critical guide along the way.

If you’d have asked me in my twenties if I’d ever retire early from Microsoft, I’d have told you that you were crazy. I loved the magic of software, and the ever-rising learning curve that Microsoft provided. It was hard for me to imagine anything else I’d rather do.

By my mid-forties my perspective was changing. The U.S. government’s antitrust suit against Microsoft had drained me, sucking some of the joy out of my work. Stepping down as CEO in early 2000, I hoped to focus more on building software products, always the best part of my job.

Also, my world view was broadening. Both Melinda and I were feeling a strengthening pull toward our young foundation and its work in U.S. education and the development of drugs and vaccines for diseases in poor countries. For the first time in my adult life I allowed myself space for non-Microsoft reading, soaking up books on the immune system, malaria and the history of plagues just as I had once scoured The Art of Computer Programming.

With our commitment to philanthropy growing, Melinda and I transferred $20 billion of Microsoft stock to our foundation, making it the largest of its kind in the world. Within a year I’d taken my first overseas trip for the foundation, to India, where I squeezed drops of polio vaccine into babies’ mouths. Melinda traveled to Thailand and India to study how those countries were handling AIDS.

Our good friend Warren Buffett was curious about this new journey we were on. So in the fall of 2001, he invited me to a resort in West Virginia and asked me to speak to a group of business leaders about what Melinda and I were learning.

I’m not a natural public speaker. But at Microsoft, speech after speech, year after year, I learned to step out on a stage and paint a vision of technology for our customers, partners and the media. It helped that people wanted to hear about the white-hot software industry. I grew to enjoy it.

I felt like I was starting over with our foundation. At big global meetings, like the World Economic Forum, people flocked to hear me detail some cool piece of software, but the crowd and the energy would be gone when later that day I’d announce an innovative plan to get vaccines to millions of children.

At the time, many people I met thought health problems in low-income countries were so big and intractable that no amount of money could make any significant difference. I could see why. It was easy to ignore death and disease happening so far away. And so much of what we read in the news about global health focused on doom and gloom. This frustrated me. The problems were real enough, but so is the power of human ingenuity to find solutions. Melinda and I felt a strong sense of optimism, but we didn’t see that reflected in these stories.

Right around the time Warren asked me to give the talk, Melinda and I were trying to figure out how we might use our voices to raise the visibility of global health. Would anyone listen?

My speech to Warren’s friends was a chance to practice. If I could stir them, it would be a step towards persuading the people with the power to make the biggest difference: the legislators and heads of countries who decide how much money flows into foreign aid and global health.

I was a little nervous heading to the conference room where Warren’s group was gathered—but more than that, I was exhausted. We were in the midst of negotiations over the antitrust case, and I’d been on the phone with lawyers deep into the night. I hadn’t had time to write a full speech. I’d just jotted notes between calls, trying to simplify all we had learned into the clearest possible story.

I started talking, haltingly at first. Our big revelation, I explained, had come in the mid-1990s when Melinda and I realized how much misery in poor countries is caused by health problems that the rich world had stopped trying to solve because we’re no longer affected by them. That incensed us. The cost of that inequity at the time was three million children dying ever year, I said.

Those deaths, we realized, weren’t caused by a bunch of runaway diseases, but by a handful of illnesses that are largely treatable. Diarrhea and pneumonia alone were responsible for half of the deaths among children. Many of those children could be saved with medicines and vaccines that already existed. All that was lacking were incentives and systems to get those life-saving technologies to the people and places where they were needed—and some new inventions to speed the change.

Our philanthropy, I explained, followed the same philosophy that guided Microsoft: relentless innovation. The right vaccine can wipe a deadly virus off the planet. A better toilet can help stop diarrheal disease. Investments in science and technology can help millions to survive their childhood and lead healthy productive lives—potentially the greatest return in R&D spending ever.

As I spoke, the legal tangles that had consumed me the night before vanished. I was energized. When ideas excite me, I rock, I sway, I pace—my body turns into a metronome for my brain. For the first time, all the facts and figures, anecdotes and analyses cohered into a story that was uplifting—even for me. I was able to make clear the logic of our giving and why I was so optimistic that a combination of money, technology, scientific breakthroughs, and political will could make a more equitable world faster than a lot of people thought.

I could tell from the nods and laughs and caliber of questions that the group got it. Afterward, Warren came over with a big smile. “That was amazing, Bill,” he said. “What you said was amazing, and your energy around this work is amazing.” I grinned back at him. Three ‘amazings’—a first.

The confidence I found that day encouraged me to take a more public role on global health issues. Over the next year, I refined my message at events and in interviews. I spent more time talking about health with government leaders. (That’s now a big part of my job.)

But something else had happened, too. The speech helped me see more clearly a life for myself after Microsoft, centered on the work that Melinda and I had started. Software would remain my focus for years and I will always consider it the thing that most shaped who I am. But I felt energized to get further along this new path we were traveling, to learn more and to apply myself to the obstacles in the way of more people living better lives. Eventually, I would retire from Microsoft almost a decade earlier that I had planned. The 2001 speech was a step, a private moment, on the way to that decision.

Now I get to focus every day on trying to deliver the vision I outlined in that conference room almost two decades ago. The world is more equitable now than it was then. But we’ve still got a long way to go. By letting Netflix’s cameras in, I hope you can see the joy I get from my work and why I am so optimistic that with ingenuity, imagination, and determination, we can make even more progress towards that goal.

Calculated risk

A bet on humanity worth every dollar

The story behind one of the riskiest ventures our foundation has ever attempted.

In Part 2 of the Netflix documentary series Inside Bill’s Brain, the director notes that my analytical approach to my job isn’t particularly inspiring. He’s got a point. I describe what I do as “optimization”—a wonky way of saying I try to make sure our limited resources help as many people as possible. I’ll never be the intrepid health worker on the front lines fighting disease. But if our foundation and its partners can help that worker reach more children with better tools, we all can create better lives for generations to come. Our decision to fight polio is one of the best examples.

In 2007, our foundation joined a decades-long effort to eradicate polio. We made our first big grants for what we thought would be a five-year, final push to end polio, a disease that had terrorized the human race for thousands of years. Over a decade later we are still pushing. Risky bet? Yes, but I think we were right.

The Netflix documentary talks a lot about my willingness to dive into projects, like polio eradication, where there’s no guarantee of success. In the second episode, my friend Bernie describes me as a risk taker, making his point with a story that involves a surfboard, a volcano, and a dislocated shoulder.

Watching the series got me thinking about what the word “risk” really means. In the polio fight, the risk takers are the thousands of health workers and volunteers braving war zones and getting to some of the hardest-to-reach places on earth to deliver vaccines to kids. They are the heroes of polio eradication.

The risks I take are more like what Warren Buffett does when he makes an investment on the bet that it will be worth ten times as much down the road. Warren spends a lot of time looking for a company that has great long-term prospects. Then he makes a big investment and holds it for many years. He’s famous for staying the course through market gyrations and economic cycles.

Our foundation isn’t after financial gain, but we’re aiming for similar ten-fold returns in social impact—in people living better-educated, more productive, longer and healthier lives. Like Warren, Melinda and I pick our areas of focus carefully. Whether we invest $100,000 or $100 million, the decision is always calculated. I spend a lot of time thinking, analyzing data, and talking to experts to judge whether we can really help make a difference. It’s the part of my job I love the most. I’m never happier than when I’m diving deep into the details of a problem, to understand how any proposed solution would work—or fail.

I also feel pressure to make every dollar and every day count. Warren gifted our foundation his wealth to make the world better, and Melinda and I feel a lot of responsibility to use that gift wisely. I say no to a lot more opportunities than I say yes to.

Ultimately, no matter how much analysis we do, I have to be comfortable with a lot of uncertainty. We are tackling problems where progress is measured not just in years but often decades—where your end goal doesn’t change, but your path to get there might have to. The trick is to do whatever I can to keep learning and to be open to new and novel ways to bring us a step closer to our goals. That approach has guided every big bet I’ve made in my career from Microsoft to today—including polio.

In the spirit of the title of the documentary, here’s a look at what I was thinking when we took that bet and set our foundation on one of the riskiest ventures it’s ever attempted.

I had a model in my mind: smallpox, the only human disease ever successfully wiped out. Smallpox was one of humanity’s big killers—at least 300 million people died of it in the 20th century alone. But by 1980, the disease was gone, thanks to a concerted push by global health organizations and thousands of dedicated health workers. That’s one of the greatest achievements of our age.

Early on, Melinda and I were lucky to work with Bill Foege, a key architect of that feat. He made it clear to me why eradicating a disease is a gift to all future generations. People are freed forever from a deadly threat, while the resources that were devoted to fighting that disease are freed up for solving other problems. Plus, victory is energizing: the defeat of smallpox helped inspire a global push to raise vaccination rates and lower childhood mortality. Such benefits, Bill Foege said, can make eradication “the ultimate return on investment.”

Galvanized by the smallpox success, health ministers from United Nations member states came together in 1988 and targeted polio as the next disease to go. They formed the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI)—a partnership that includes WHO, Rotary International, UNICEF and CDC.

Polio can wither limbs, paralyze lungs, and even kill. There is no cure. And yet we’ve long had the means to prevent the disease: with a cheap, safe, easy-to-administer vaccine. When the GPEI started running vaccination campaigns in 1988, polio was paralyzing 350,000 people a year. By 2007, there were only about 1,300 cases—but progress had stalled, raising the risk that the virus would surge back, and decades of gains would be lost. At the time, I was soaking up everything I could on eradication, its history, science, and epidemiology. I had only seen one polio vaccination campaign (in India) so I planned more trips.

Bill Foege and others at the foundation put together a team and we walked through the possible advances that could help us break through. Polio travels with stealth; nine out of ten people who are infected develop mild symptoms, if any, but can still spread the virus to others. So to stop it, you have to reach nearly every child with multiple doses of the vaccine over time.

That takes money and organization; it requires political cooperation and parents who trust the process and are willing to have their children be immunized. It takes an army of volunteers and trained health workers who can be counted on to knock on doors throughout a village in search of every last child and keep accurate records of who they immunized and who they missed. Stopping polio requires scientists and trained people on the ground watching out for reports of children whose limbs become abruptly paralyzed. None of the countries where polio remained in 2007 had all the pieces needed to complete that puzzle. That was the challenge, but also where we saw opportunities.

We bet that with innovations including better disease surveillance and improved mapping, we could get a clearer picture of where the virus was hiding, and that computer models could better predict where it might go. We saw ways to increase the number of vaccination campaigns and improve their quality. Deploying precise genetic tests to sample sewage could help us track the travels of different strains of the virus in the environment before it paralyzed children.

We spent about six months studying the problem and then dove in. Back then I was sure we’d be done with polio by now.

Ten years have taught us a lot. For all the great technologies and fresh ideas about how to stop polio, the real test is how they play out on the ground—in the villages and clinics of the last few countries where the disease has dug in. Unfortunately, in some places, these last steps to eradication have been slowed by risks that I underestimated, including war and political unrest. But in far more places, we’re beating the disease, as people, from parents to presidents, commit to the hard work of ending polio.

As of 2011, polio was completely gone from India, a country that experts thought would be the last place to wipe out the virus because of its size, complexity and the fact that tens of millions of its citizens live in extreme poverty. The children most at risk were in underserved, inaccessible regions, where they were often missed because of their families’ frequent moves in search of work. But leaders at all levels of government made it a priority to find those children—setting up vaccine booths in train stations, sending out vaccinators on motorbikes, boats and donkeys—and halt the disease.

In Nigeria, both traditional religious leaders and local, state and federal officials have been instrumental in building community trust in the polio program, ensuring parents allow their children to be immunized, and strengthening the quality of the vaccination campaign. It’s commitment like this that has enabled Nigeria to reach three years without a single case of wild poliovirus, which means Africa could be certified wild polio-free in 2020. This is unprecedented progress.

Global cases of wild polio this year have ticked up from the 33 cases last year, and no doubt we’ll face new challenges as we focus on Afghanistan and Pakistan, the two remaining countries where the virus has yet to be stopped. The job is to keep moving forward, adjusting to the unexpected with new ideas and energy so we can reach the last unprotected child and achieve a polio-free world. That’s a bet worth every dollar.