Road trip

A novel about going west in a Studebaker

I loved the latest from the author of A Gentleman in Moscow.

Whenever I choose a novel and put it in my canvas book bag, I optimize for great storytelling—almost regardless of the topic. One of my new favorite storytellers is the writer Amor Towles. In 2019, I reviewed his book A Gentleman in Moscow, which was fantastic. So it was a no-brainer to pick up his next novel, The Lincoln Highway, when it came out last October.

Once again, I was wowed by Towles’s writing—especially because The Lincoln Highway is so different from A Gentleman in Moscow in terms of setting, plot, and themes. Towles is not a one-trick pony. Like all the best storytellers, he has range.

The title of this latest book refers to America’s first cross-country roadway for automobiles, which stretched from New York City to San Francisco. The story takes place over ten days in 1954, when two young brothers, Emmett and Billy, intend to drive their Studebaker from Nebraska to California. (I could picture the car clearly—my dad had one too.) But fate, in the form of a sympathetic but volatile character named Duchess, forces them to travel in the opposite direction before they can have a chance to start fresh in the West.

Towles takes inspiration from famous hero’s journeys, including The Iliad, The Odyssey, Hamlet, Huckleberry Finn, and Of Mice and Men. He seems to be saying that our personal journeys are never as linear or predictable as an interstate highway. But, he suggests, when something (or someone) tries to steer us off course, it is possible to take the wheel.

My favorite character is Billy, an eight-year-old who has endured abandonment by his mother and the death of his father. At the beginning of the story, when Billy’s brother, Emmett, returns home after 15 months of juvenile detention, Billy comes across as a sweet but hapless dreamer who has survived by escaping into adventure stories. By the end of Billy and Emmett’s journey east, it’s clear that Billy is anything but a tragic figure. He is amazingly clever and resilient. In that way, he reminds me of Nina, the precocious nine-year-old from A Gentleman in Moscow.

Emmett also seems like a tragic character early on. He has the tragic flaw of anger: His juvenile detention was the result of punching (and inadvertently killing) a bully who was taunting him. But Emmett finds ways to overcome his temper.

Another hero is Sally, a young neighbor who cares deeply for both Billy and Emmett. I think she represents a type of kindness that’s been almost non-existent for Billy or Emmett. Sally turns out to be a bold and wise character—she bristles at the strictures placed on women in 1950s America and has what it takes to overcome them. We don’t know if she and Emmett fall in love; Towles doesn’t give his story such a tidy narrative. But I suspect most readers will hope they end up that way.

I definitely finished Lincoln Highway hoping that Towles is busy writing his next novel. It almost doesn’t matter what time or place he decides to write about. I just know I’ll want to read it.

Under the sea

Growing older with Remarkably Bright Creatures

Shelby Van Pelt’s novel was the perfect way to start my next decade of life.

I turned 70 years old last month. I don’t feel like it, though. I still have a ton of energy, and I have no plans to retire. But somehow, I have officially reached an age my younger self would have called “old.” It’s hard to wrap my head around.

Fortunately, I recently read Remarkably Bright Creatures, a terrific novel that helped me make a bit more sense out of aging. Shelby Van Pelt released her debut novel a couple years ago. It was a huge hit, and I think I might be one of the last people to read it—but I’m glad I waited until now.

Tova, the main character, is also 70, and she feels every single one of those years. Her life hasn’t been easy. Tova’s son is presumed dead after he disappeared when he was a teenager, and her husband died from cancer five years earlier. To pass the time, she works night shifts cleaning the local aquarium, which is where she meets Marcellus, an elderly giant Pacific octopus who is nearing the end of his life.

Marcellus is a fascinating character. Octopuses are some of the smartest animals in the world, and although Marcellus can’t speak, he is super observant. Van Pelt cleverly includes chapters from his perspective, so you get to learn about how he sees the world. He considers Tova a friend after she rescues him after a late-night excursion from his tank goes dangerously wrong. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but Marcellus’s power of observation ends up changing the lives of many of the books’ characters.

Tova gets a much-needed sense of fulfillment from caring for Marcellus and the aquarium. She struggles with purpose throughout the book. Her friends are motivated by their grandchildren, but without her husband and son, Tova feels aimless and alone (even though the reader knows that she has plenty of people in her life who love her—including Ethan, the owner of the local grocery store). Early in the book, she feels so lost that she considers moving away from her hometown and into a senior living community.

Tova’s struggle is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about, because I worry that we might soon see more people feeling like her. As life expectancies go up, many people are living for years and even decades after they stop working. That sounds like a luxury, and it is in a lot of ways—but it is also a lot of time to fill. The decline of third places like churches and libraries makes it harder than ever to find connections that keep the days interesting. Fewer families are having children, which means that fewer older people are becoming grandparents. And while part-time work can help give life meaning, not everyone is physically capable of working.

“Tova has always felt more than a bit of empathy for the sharks, with their never-ending laps around the tank. She understands what it means to never be able to stop moving, lest you find yourself unable to breathe,” Van Pelt writes. Her message is clear: People need a reason to get out of bed in the morning. For many, it’s hard to transition from a lifetime of working to retirement. So, what can we do to help older people find purpose? And how can we prepare for a potential future where technological advances mean all of us have less work to fill our days?

Remarkably Bright Creatures doesn’t try to answer those questions, but Tova’s story really makes you think about how people find meaning in life. Her story is mirrored by Cameron’s, a young man who struggles to find his own purpose and ends up working with Tova at the aquarium. Although their lives couldn’t be more different, I loved seeing how Tova and Cameron help each other find reasons to get out of bed over the course of the story (with help from Marcellus the octopus).

I think anyone who enjoys fiction would enjoy this book, but it’s a must-read for people who grew up in Western Washington like I did. The novel takes place in Sowell Bay, a fictional coastal town that will feel familiar to anyone who has spent time around Puget Sound. Van Pelt captures the specific feeling of weathered charm you get when you visit places like Hood Canal or Anacortes.

I usually read non-fiction books, but Remarkably Bright Creatures gave me exactly what I want whenever I pick up a novel. It transported me to a different world, and it illuminated something new for me—in this case, about relationships and getting older. Reading Tova and Marcellus’s story was the perfect way to start my next decade of life.

On the frontlines

The Women gave me a new perspective on the Vietnam War

Kristin Hannah’s wildly popular novel about an army nurse is eye-opening and inspiring.

When I was 15 years old, one of my teachers took me to my first Vietnam War protest.

My teacher ended up getting in a bit of trouble for it, but I’m thankful he took us. The war was such a centerpiece of what was going on in the 1960s. It was incredible to experience what seemed like (and turned out to be) history in the making. I remember feeling like I was a very small part of something big.

I thought about that experience a lot while I was reading The Women by Kristin Hannah. This terrific novel tells the story of Frankie McGrath, an army nurse who serves two tours on the frontlines in Vietnam before returning home to a country rocked by protest and anti-war sentiment.

I wasn’t familiar with Kristin Hannah before reading The Women, even though she’s written a number of books that have done quite well (and this one is already a huge hit). My brother-in-law John—who served two tours in Vietnam and found the book fantastic—recommended it to me when he found out I was headed there for vacation. I actually read the book in Da Nang, which was where U.S. troops first landed back in 1965.

Although I’ve read and watched a lot about the war in Vietnam, The Women made me think about it in a new light. I didn’t know about the critical role so many women played, and it was both eye-opening and inspiring to learn more about the frontline nurses who saved countless lives.

At the beginning of the book, Frankie is inspired to enlist in the army after a friend suggests that women can also be heroes. She grew up looking at her father’s wall of veterans in his office, where portraits hung of all the male family members who had served. Hannah writes, “Why had it never occurred to Frankie that a girl, a woman, could have a place on her father’s office wall for doing something heroic or important, that a woman could invent something or discover something or be a nurse on the battlefield, could literally save lives?”

The book makes it clear that Frankie and her colleagues are true heroes—but their presence in Vietnam is largely ignored and forgotten, even by those who served with them. In one particularly memorable scene after she returns from war, Frankie seeks mental health treatment at her local VA hospital. It’s clear that she is suffering from PTSD and needs help. But the hospital turns her away because she is a woman and, therefore, couldn’t possibly be a veteran.

Frankie hears the phrase “there weren’t women in Vietnam” from her fellow veterans over and over in the book. What they mean is that women weren’t on the frontlines. But as the book makes clear, if you’re in a medical role near the war front, you experience every bit of the trauma of war. Frankie treats hundreds of people who died or suffered life-changing wounds. She is forced to hunker down whenever the base she works on is under attack. There are moments when she thinks she is going to die. Her time overseas is grim and horrifying, and I can’t imagine how devastating it must have been for real female Vietnam veterans to have their experiences discounted after coming home.

This is a novel, of course, and not a history book. But the author spent a lot of time talking to female Vietnam veterans about their experiences, and the depth of her research comes through in the writing.

I was especially interested to read about Frankie’s slow revelation that the U.S. government has been lying about the war. When she first arrives in Vietnam, she believes that the U.S. is winning the war. Over time, she begins to notice that the upbeat message coming from the military leadership doesn’t match with what she’s experiencing on the ground. After one particularly gruesome day of fighting, Frankie’s friend and coworker Barb notes that “the Stars and Stripes reported no American casualties yesterday. Seven men died in OR One alone.”

I remember watching the nightly news with my parents during the war and hearing that way more North Vietnamese soldiers had died than American soldiers. The government told us that casualty counts were the figure of merit, and by that measure, we were winning the war. Later, we found out the numbers had been distorted. And death totals were not even the right metric in the end, because the North Vietnamese were fighting for their very existence. The number of men they could call up at will was way beyond anything we could ever deal with. (I highly recommend reading H.R. McMaster’s book Dereliction of Duty if you want to learn more about this.)

The Women is an important reminder that no one was more impacted by these lies than the brave men and women serving overseas. They were sent to the frontlines of an unwinnable conflict, and they returned home to a nation that had turned against both the war and the people who served in it. Frankie reflects that “the world of hippies and protesters felt far, far away. It had nothing to do with the guys dying over here. Except that it did. The protests made them feel that their sacrifices meant nothing or, worse, that they were doing something wrong.”

I like to think that has changed by now. Enough time has passed that most people acknowledge the individual heroism that took place in Vietnam, even though history doesn’t look kindly on the war itself. People over there did things that we can—and should—be proud of. That’s one reason why I’m glad to see a book like The Women doing so well. It’s a beautifully written tribute to a group of veterans who deserve more appreciation for the incredible sacrifices they made.

Co-op mode

This novel about video games felt personal to me

I never thought I’d relate to a book about gaming, but I loved Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.

Am I a gamer? For a long time, I would have said no because I don’t spend hundreds of hours going deep on one game.

But when I was younger, I loved arcade games and got very good at Tetris. And in recent years, I have started playing a lot of online bridge and games like Spelling Bee and a bunch of the Wordle variants. The definition of a gamer is becoming a lot broader and more inclusive, and it might be fair to start calling me one.

Either way, I don’t think you need to be a hardcore gamer to enjoy Gabrielle Zevin’s terrific novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. It tells the story of Sam and Sadie, two friends who bond over Super Mario Bros. as kids and grow up to make video games together. Tomorrow was one of the biggest books of last year, and it’s easy to see why. Zevin is a great writer who makes you care deeply about her characters.

Although there are plenty of video games mentioned in the book—Oregon Trail is a recurring theme—I’d describe it more as a story about partnership and collaboration. When Sam and Sadie are in college, they create a game called Ichigo that turns out to be a huge hit. Their company, Unfair Games, becomes successful, but the two start to butt heads. Sadie is upset that Sam got most of the credit for Ichigo. Sam is frustrated that Sadie cares more about creating art than about making their company viable.

Zevin is such a good writer that she makes you sympathize equally with both of them. Female game developers often struggle to receive recognition, so Sadie’s position is understandable. But she also comes from a well-off family unlike Sam, who grew up poor and sees Unfair Games as his gateway to achieving financial stability for the first time. Most of the book is about how a creative partnership can be equal parts remarkable and complicated.

I couldn’t help but be reminded of my relationship with Paul Allen while I was reading it. Sadie believes that “true collaborators in this life are rare.” I agree, and I was lucky to have one in Paul.

An early chapter describing how Sam and Sadie worked until sunrise in a dingy apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, could have just as easily been about Paul and me coming up with the idea for Microsoft. Like Sam and Sadie, we worked together every day for years. Paul’s vision and contributions to the company were absolutely critical to its success, and then he chose to move on. We had a great relationship, but not without some of the complexities that success brings.

Zevin really captures what it feels like to start a company that takes off. It’s thrilling to know your vision is now real, but success brings a lot of new questions. Once you make money, do you still have something to prove? How does your relationship with your partner change once a lot more people get involved? How do you make the next idea as good as the last?

You can’t help but wonder whether you would’ve been as successful if you started up at a different time. Sadie says, “If we’d been born a little bit earlier, we wouldn’t have been able to make our games so easily. Access to computers would have been harder… And if we’d been born a little bit later, there would have been even greater access to the internet and certain tools, but honestly, the games got so much more complicated; the industry got so professional. We couldn’t have done as much as we did on our own.” I know what she means: Paul and I were very lucky in terms of our timing with Microsoft. We got in when chips were just starting to become powerful but before other people had created established companies.

Another part of the book that felt familiar to me was Sam and Sadie’s dynamic with Marx, a college friend who is an equal partner in their work. Marx isn’t a game designer like Sam and Sadie, but Ichigo and Unfair Games wouldn’t have happened without his production and business savvy. He’s also a charming, funny character who you can’t help but root for throughout the book.

If Paul and I were Sam and Sadie, Steve Ballmer was our Marx. He didn’t write code, but the success of Microsoft was highly dependent on him. Like Marx, Steve made sure we hired the right people and had the tools we needed for the company to take off. The comparison isn’t perfect: We always appreciated Steve’s value, but in the book, Sam comes to resent Marx and downplays his contributions. (And of course Steve became Microsoft’s CEO, a position that Marx never reaches at Unfair Games.) But Zevin understands that dreamers alone can’t turn big ideas into reality—you need doers, too.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow resonated with me for personal reasons, but I think Zevin’s exploration of partnership and collaboration is worth reading no matter who you are. Even if you’re skeptical about reading a book about video games, the subject is a terrific metaphor for human connection. As Zevin writes, “To allow yourself to play with another person is no small risk. It means allowing yourself to be open, to be exposed, to be hurt. To play requires trust and love.”

To be or not to be

Hamnet pierces the boundary between real life and play

Maggie O’Farrell’s novel is a beautiful, well-written look at how grief tears a family apart.

If you live in the Pacific Northwest, you can’t find a better place to see a play than the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. I’ve been six or seven times, and I’m always blown away by the productions they put on. Some of the shows take place in this gorgeous outdoor theater that’s decorated like it’s from the Elizabethan era. There’s something special about seeing A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Othello under the stars.

The festival has made me even more of a fan of Shakespeare than I already was. I’m in awe of the timelessness and cleverness of his plays. It’s amazing how vivid, clever, and poignant his work remains centuries later.

But who was Shakespeare really? We know shockingly little about the man behind the plays, although there have been a lot of films and books speculating about his personal life. (I’m particularly a fan of Shakespeare in Love.) Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet is the latest, and I thought it was a beautiful, well-written look at how grief tears a family apart.

O’Farrell centers her book on two things that we know are true: Shakespeare’s son Hamnet died at 11 years old, and Shakespeare wrote a tragedy called Hamlet just a couple years after his passing. (Many scholars believe that the names Hamnet and Hamlet were interchangeable in his era.) She explores the days leading up to Hamnet’s death and hypothesizes about how that event may have influenced the writing of one of the greatest plays of all time.

The most interesting choice she makes is to focus not on Shakespeare himself but on his family instead. The words “William” and “Shakespeare” are never used, and if you didn’t know what the book was about, I don’t know if you would recognize who “the husband” is until the end. You develop sympathy for him, but it’s really his wife, Agnes Hathaway, and their three children who are at the center of the story.

Agnes (whom most people probably know as Anne) is a fascinating character. She’s been painted by history as a calculating woman who trapped the much younger Shakespeare into marriage by getting pregnant, but O’Farrell has a different take on her. This Agnes is a mysterious and almost supernatural figure who has a deep connection with nature. She’s a talented healer who can see the future—she knows her first child will be a girl and that only two of her children will live to watch her die.

Most of Stratford-upon-Avon is afraid of her, but Shakespeare is drawn to the things that make her different and falls in love with her. When telling his sister about Agnes, he says, “She is like no one you have ever met... She can look at a person and see right into their very soul. There is not a drop of harshness in her. She will take a person for who they are, not what they are not or ought to be.”

When two of their children fall ill—first their younger daughter Judith, and then her twin Hamnet—Agnes is forced to care for them on her own. Shakespeare is in London working in the theater, and he only finds out that they’re sick once it’s too late.

No one knows what killed the real Hamnet. O’Farrell proposes that it was the bubonic plague, which is plausible for that era. It’s interesting to read about the plague right now, because it was such a different kind of pandemic than the current one. You wouldn’t see big outbreaks across entire communities. It would seem to show up randomly in a household, which is what happens to Agnes’s family.

You know from the beginning that Hamnet’s story is going to end in tragedy. It’s a testament to how talented of a writer O’Farrell is that you can’t but believe it might turn out differently and that Agnes might save him. It reminded me a bit of the George Saunders novel Lincoln in the Bardo. Both books imagine how historical figures would’ve responded to the loss of a child, although Bardo is a lot more fantastical. Sadly, this wasn’t an uncommon situation. Only two-thirds of children lived to see their fifth birthdays in Lincoln’s time, and the odds were much worse in Shakespeare’s day. O’Farrell and Saunders capture how devastating and shocking it is to lose a child, even in an era when it was somewhat expected.

Hamnet is ultimately a story about how the death of a son haunts his parents, while Hamlet is a tale about how the death of a parent haunts his son. O’Farrell cleverly ties the two together and offers a moving explanation for how Shakespeare channeled his grief and guilt into writing. She makes me want to go back and re-read the play.

If you’re familiar with Shakespeare’s writing, I think you’ll enjoy Hamnet. It’s surprisingly easy to read, even though the subject matter is heavy. I would describe it as emotional rather than depressing. At the end of the book, Agnes says she wishes she could “pierce the boundary between audience and players, between real life and play.” O’Farrell has done a remarkable job crossing that line and imagining how real life may have influenced one of history’s greatest plays.

Out of the woods

This novel changed how I look at trees

If you are in the mood for something that stimulates your thinking, you’ll love The Overstory.

I grew up (and still live) in a place known for its beautiful forests. Almost everywhere you look here in Washington state—at least in the western part of it—you can find massive fir trees and towering red cedars. When you spend most of your life here, it’s tempting to take them for granted. But what would happen if one day you woke up and they were gone?

In The Overstory by Richard Powers, Mimi Ma arrives at her office one morning to find that the woods she can see from her desk have been cut down. Powers describes the moment the “outrage floods into her, the sneakiness of man, a sense of injustice larger than her whole life, the old loss that will never, ever be answered.” This reaction starts her on a path to become a radical activist willing to throw her entire life away to protect trees.

Mimi is just one of the nine characters that Powers follows in The Overstory, which won the Pulitzer Prize two years ago. Each character has some kind of connection to trees, including a Vietnam veteran who gets a job planting seedlings and an artist whose family has been photographing the same chestnut tree for a century. I thought the most interesting was Olivia Vandergriff, a college student who becomes a tree sitter named Maidenhair after being nearly electrocuted to death.

A good friend thought I might enjoy reading about all the different stories, and he was right. This isn’t a book where everything gets tied up with a bow. Some of the characters meet up with each other, and others have totally separate stories. In the end, it’s not clear whether you’re supposed to see their actions as morally right or just kind of crazy. (You don’t even find out whether one of the main characters lives or dies.)

I didn’t mind the lack of clarity, but some other people might. If you are in the mood for something that stimulates your thinking instead of providing answers, though, you’ll love The Overstory. It’s very well-written and takes twists you wouldn’t expect.

The book made me want to learn more about trees. You don’t need any special knowledge to follow the story, but it left me super curious about the subject. There’s a certain elegance to how trees fit into their ecosystems. It’s amazing that they live for so long—the oldest tree in the world is over 4,800 years old!—despite being stationary.

Powers is interested in the damage humans can do to something that has otherwise withstood hundreds of years of change. It’s a fascinating idea for a book, although I don’t subscribe to his idea that the world started off in this positive state and has been going downhill since we came along. I think the relationship between people and nature is a bit more complicated than The Overstory suggests. (I wrote more about this in my review of Under a White Sky.)

The novel has a pretty negative view of humanity. That didn’t make me enjoy it any less. On the contrary, I loved following Powers’ characters as they became more and more passionate about their love for trees. There was something pure about the way they set aside their individual needs for a greater cause, even as several of them make choices that I strongly disagreed with—including the decision to commit acts of ecoterrorism.

Near the end of the book, Powers writes that “the most wondrous products of four billion years of life need help.” The Overstory may not have convinced me to move to a remote forest so I can live in a canopy, but it did make me think differently about my relationship with the trees right outside my window.

A lot o’ true

A wonderful, mind-bending novel

Cloud Atlas is a touching and very clever story about moral choices.

Cloud Atlas is a wonderful book that is hard to describe. I can tell you that it is a touching and clever novel about moral choices. It explores how self-centered and bad people can be, but also how supportive and good people can be. Yet if you haven’t already read it (it came out in 2004) or seen the movie with Tom Hanks and Halle Berry, I suspect that my summary of the plot will make it sound quite strange.

Written by the British author David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas is made up of six inter-related stories set in different times and places. One involves a young American doctor on a sailing ship in the South Pacific in the mid-1800s. Another—a very funny story about an editor caught up with gangsters—is set in London in the 2000s. Two are set in the future, one after an apocalypse has set civilization back to something like the Stone Age and people speak in a distinctive way. (“Most yarnin’s got a bit o’ true, some yarnin’s got some true, an’ a few yarnin’s got a lot o’ true.”)

In each story, at least one character is the reincarnation of someone from a previous story. Mitchell doesn’t come out and tell you that explicitly, though. He reveals it through hints, including a recurring birthmark that shows up on different characters. Although I think you could enjoy the novel without worrying too much about what this means, it’s fun to try to catch all the connections in the different stories.

Just to complicate things even more, the novel has a mind-bending nested structure. I had never come across anything quite like it in a book before. Most of the stories are split into two parts. You read part of the first story, and then at an important turning point, the book suddenly jumps mid-sentence to the next story. After a while, the second one switches unexpectedly to a third tale, and so on. Eventually, they pick up in reverse order, so the last thing you read is the conclusion of the story you started on page 1.

You might be tempted to quit reading the book if a new story does not grab you right away. I was a bit worried when the setting switched from the South Pacific to something about a young musician in 1930s Belgium—the first part had been so compelling, I wanted to know what happened. But Mitchell does such a great job of capturing the different worlds and the characters’ inner voices that I never wanted to stop reading. And I was eager to see how he would connect each story to the ones that came before.

In a way, what the stories have in common is just as important as what makes them different. This is a grand tale about human nature and human values—the things that change and the things that don’t, over hundreds or even thousands of years.

I wish I could remember who recommended Cloud Atlas to me, because it’s the kind of book you’ll want to discuss with someone else. I’m sure that I didn’t catch everything going on—reading it is a bit like putting together a puzzle—and I’m hoping to persuade Melinda or a friend to pick it up so we can share the different pieces of the puzzle that we figured out. You’ll think and talk about Cloud Atlas for a long time after you finish reading.

Out for the count

A Gentleman in Moscow has a little bit of everything

Towles’s novel is technically historical fiction, but you’d be just as accurate calling it a thriller or a love story.

Melinda and I sometimes read the same book at the same time. It’s usually a lot of fun, but it can get us in trouble when one of us is further along than the other—which recently happened when we were both reading A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.

At one point, I got teary-eyed because one of the characters gets hurt and must go to the hospital. Melinda was a couple chapters behind me. When she saw me crying, she became worried that a character she loved was going to die. I didn’t want to spoil anything for her, so I just had to wait until she caught up to me.

That one scene aside, A Gentleman in Moscow is a fun, clever, and surprisingly upbeat look at Russian history through the eyes of one man. At the beginning of the book, Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov is sentenced to spend his life under house arrest in Moscow’s Metropol Hotel. It’s 1922, and the Bolsheviks have just taken power of the newly formed Soviet Union. The book follows the Count for the next thirty years as he makes the most of his life despite its limitations.

Although the book is fictional, the Metropol is a real hotel. I’ve even been lucky enough to stay there (and it looked mostly the same as Towles describes in the book). It’s the kind of place where you can’t help but picture what it was like at different points in time. The hotel is located across the street from the Kremlin and managed to survive the Bolshevik revolution and the rise and fall of the Soviet Union. That’s a lot of history for one building.

Many scenes in the book never happened in real life (as far as I know), but they’re easy to imagine given the Metropol’s history. In one memorable chapter, Bolshevik officials decide that the hotel’s wine cellar is “counter to the ideals of the Revolution.” The hotel staff is forced to remove labels from more than 100,000 bottles, and the restaurant must sell all wine for the same price. The Count—who sees himself as a wine expert—is horrified.

Count Rostov is an observer frozen in time, watching these changes come and go. He felt to me like he was from a different era from the other characters in the book. Throughout all the political turmoil, he manages to survive because, well, he’s good at everything.

He’s read seemingly every book and can identify any piece of music. When he’s forced to become a waiter at the hotel restaurant, he does it with this panache that is incredible. He knows his liquor better than anyone, and he’s not shy about sharing his opinions. The Count should be an insufferable character, but the whole thing works because he’s so charming.

Towles has a talent for quirky details. Early-ish in the book, he says the Count “reviewed the menu in reverse order as was his habit, having learned from experience that giving consideration to appetizers before entrees can only lead to regret.” A description like that tells you so much about a character. By the end of the book, I felt like the Count was an old friend.

You don’t have to be a Russophile to enjoy the book, but if you are, it’s essential reading. I think early 20th century Russian history is super interesting, so I’ve read a bunch of books about Lenin and Stalin. A Gentleman in Moscow gave me a new perspective on the era, even though it’s fictional. Towles keeps the focus on the Count, so most major historical events (like World War II) get little more than a passing mention. But I loved seeing how these events still shifted the world of the Metropol in ways big and small. It gives you a sense of how political turmoil affects everyone, not just those directly involved with it.

A Gentleman in Moscow is an amazing story because it manages to be a little bit of everything. There’s fantastical romance, politics, espionage, parenthood, and poetry. The book is technically historical fiction, but you’d be just as accurate calling it a thriller or a love story. Even if Russia isn’t on your must-visit list, I think everyone can enjoy Towles’s trip to Moscow this summer.

Measures of devotion

An all-American ghost story

Lincoln in the Bardo gave me a new perspective on America’s 16th president.

I find anything related to Abraham Lincoln super interesting. His personal story—of someone from humble beginnings who successfully navigated the political world without compromising his beliefs—is fascinating. I’ve read a lot about him over the years and thought I knew pretty much everything there was to know. But I recently read a book about Lincoln that surprised me.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders gave me a new perspective on America’s 16th president. Despite being a work of fiction, it offered fresh insight that made me rethink parts of his life. The novel takes place over the course of one night not long after the death of Willie, Lincoln’s beloved 11-year-old son. The “bardo” in the title refers to a purgatory-like place where spirits linger after death—in this case, a spectral version of the Washington, DC cemetery where Willie was buried.

It’s dangerous for children to linger in the bardo (for reasons that are never explained), but Willie refuses to leave after his father visits his grave. Most of the book focuses on the other spirits trying to convince Willie to depart. There are 166 spirits in total, and Saunders uses a script format to make it clear who is speaking when. It’s disorientating at first, but you get the hang of it pretty quickly.

Saunders also uses excerpts from historical texts to tell the story of Willie’s death and its aftermath. I loved how he uses these flashbacks to show how fuzzy our recollections of the past can be. In one chapter, he weaves together conflicting quotes about Lincoln’s appearance. Were his eyes gray, or were they green? The answer changes depending on who you ask. It reminded me of the musical Hamilton, which deals with similar ideas about how storytellers shape history.

Saunders blends history and fiction seamlessly throughout the book. Some of the snippets in the flashbacks come from real sources (like Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals), and others are made up. The same is true of the ghosts: some are based on real people, but most are fictional. Lincoln really did visit Willie’s grave, although scholars disagree about whether he opened the coffin as he does in the book.

Saunders’ Lincoln is a man crushed by the weight of both grief and responsibility. Although his early life had its own share of tragedy, he’s now experienced the greatest heartbreak a parent can have. “The essential thing (that which was borne, that which we loved) is gone,” he thinks as he looks down at Willie’s coffin toward the end of the book.

Losing a child is unbearable for any parent, but Lincoln is also burdened by timing. Willie died less than a year after the Civil War started. The president has a new understanding of the grief he’s creating in other families by sending their sons off to die in battle. He must make a choice. Should the war go on? If it does, how can we ensure the end result justifies the cost of such suffering?

As far as I know, there’s no evidence linking Lincoln’s decision-making in the war to his son’s death—but Saunders cleverly makes the connection. Although the Gettysburg Address isn’t mentioned in the book, the results of Lincoln’s choice are echoed in some of its most famous lines: “From these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.”

More than once while reading Lincoln in the Bardo, I found myself wanting to discuss it with someone else. A tennis buddy recommended the book to me, and I couldn’t wait to get back on the court and talk to him after I finished. Many parts of the book are intentionally mysterious. The study guide at the end is helpful, but I think it’s more fun to hear what other people think.

Lincoln in the Bardo is heavy stuff for a summer book, but I’m really glad I picked it up. It’s a quick read thanks to its play-like format, and some of the ghosts’ stories are surprisingly funny given the subject matter. If you’re an Abraham Lincoln buff like me, you won’t regret taking this one on your next vacation.

Infinite spiral

My family loved reading this book together

Readers of all ages will enjoy John Green’s latest novel, Turtles All the Way Down.

When Melinda and I did an event with John Green in New York a couple years ago, we knew we had to bring our youngest daughter, Phoebe, along. He is one of her favorite authors, and she’s converted our entire family to fans of his books.

Before we went on stage, John pulled Phoebe aside to share a secret with her: the plot of his new book. He made her promise not to share it with anyone, and she stayed true to her word for nearly two years. She wouldn’t even tell Melinda and me!

Phoebe doesn’t have to keep the secret any longer, because that book—Turtles All the Way Down—was released late last year.

I’ve read a couple of John’s books and enjoyed each one, and his latest is no exception. Turtles All the Way Down tells the story of Aza Holmes, a high school student from Indianapolis. When a local billionaire goes missing and a $100,000 reward is offered for information about his disappearance, she and her best friend decide to track him down.

Aza’s quest is complicated by the fact that she has obsessive compulsive disorder and severe anxiety. Her struggles are a huge part of the book, as her compulsions constantly get in the way of her social life. John’s writing feels almost claustrophobic when describing Aza’s mental swirl. Some people might find those parts difficult to read, but he really gives you a sense of what it feels like to live with OCD.

Because this is a John Green novel, romance must factor into the equation. Aza begins to develop feelings for Davis, the son of missing billionaire Russell Pickett. He is initially skeptical about her intentions, because he’s used to people sucking up to him to get close to his dad. While I hope I’m nothing like the morally bankrupt Russell—he wants to give all of his money to his pet lizard and was under investigation for fraud and bribery—I think my own kids can relate to some of Davis’ experiences.

John actually talked to Phoebe in New York about what it was like growing up with me as her dad. I asked her to write up her own mini-review now that’s she had a chance to read the book. Here’s what Phoebe had to say:

“For years I have been a loyal John Green fan—devouring his novels in the back of coffee shops, while traveling, and curled up on my couch. Something about the imagery of his books makes me get caught up in the fantasy of his stories, but Turtles All the Way Down hit closer to home for me than the rest. As someone who has struggled with OCD for years, I saw some of myself in the main character. But more than anything, this book struck close to home due to the intriguing character of Davis.

“Never has a book been able to capture so well what it is like to live in the shadow of someone else’s legacy. This story shows how Davis struggled to find his own identity outside of his father’s fame and wealth. Although we have very different relationships with our dads, I recognized his struggle, which also plays into my own life as I find my way in this world. This read was captivating like none other I have read before.”

Phoebe is much closer to John’s intended demographic than I am, but I think readers of all ages will enjoy Turtles All the Way Down. It’s a fun, moving story filled with quirky but relatable characters. Paper Towns is still my favorite John Green book—but my family loved talking about Turtles at the dinner table, and I think yours will, too.

Graphic insights

The mystery of mom and dad

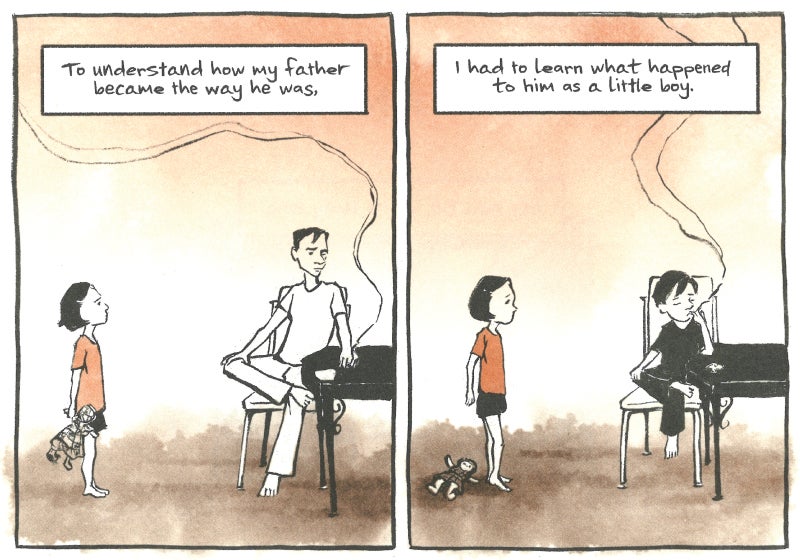

This powerful graphic novel explores parenthood and life during wartime.

How well do we really know our parents?

That’s the question Thi Bui grapples with in her stunning graphic novel The Best We Could Do. Bui is the daughter of Vietnamese refugees who came to America after the fall of Saigon. She knew that her parents were deeply traumatized by their past but never felt comfortable asking them about their experiences.

Everything changed when Bui’s son was born. The book—which is autobiographical—opens with the author giving birth as her mother slips out the door, unable to watch the delivery for reasons she doesn’t yet understand. As Bui holds her new baby, she begins to appreciate the immense responsibility that comes with parenthood—and decides to learn more about the sacrifices her parents made for her and her siblings.

What she discovers is heartbreaking. I don’t want to spoil anything, but both of her parents get sucked into the turmoil created by the foreign forces present in their country (first the French, and later the Americans). The book jumps around from family member to family member, exploring different time periods. It’s a bit confusing, but I don’t think it takes away from the powerful story.

I was struck by how the experiences Bui illustrates manage to be both universal and specific to their circumstances. Any parent will recognize many of the challenges her mom and dad faced raising their four kids. I thought she did a great job capturing how daunting it feels to be responsible for your family. At the same time, her family’s experience is different from most (and certainly mine). It’s clear that a lot of the dysfunction surrounding her childhood is a direct result of what happened in Vietnam.

After finishing The Sympathizer, I was eager to read more books written from the Vietnamese perspective. The Best We Could Do covers more of the past than The Sympathizer, which doesn’t really get into the French occupation. Bui’s memoir is more personal and a lot quicker to read.

But both books helped me better understand how Vietnam’s history shaped its people. When you grow up in the United States, it’s hard to escape the Good Morning, Vietnam view of the war—to understand how the war was awful for reasons that go beyond the draft, the protests, and even the soldiers who died on the battlefield. It was a completely horrific situation for the people who lived there, many of whom weren’t combatants on either side. In different ways, The Best We Could Do and The Sympathizer are cautionary tales about the collateral damage of war.

Despite covering such heavy subject matter, The Best We Could Do is ultimately a hopeful book. After learning what happened to her parents, Bui concludes that—even though “being their child… means that I will always feel the weight of the past”—her son doesn’t have to share the same burden. And she finally understands what’s true for all parents: when it comes to raising our kids, we simply do the best we can do.

Spy games

A fresh take on the Vietnam War

I thought this thrilling story about a double agent lived up to the hype.

I didn’t know what to expect the first time I visited Vietnam.

Although I’m a bit too young to have worried about my draft number, the Vietnam War cast a long shadow over my youth. Like many people of my generation, my view of the conflict was influenced by violent, American-centric movies like The Deer Hunter. So I was unsure when I found myself on a plane to Hanoi in 2006. Many of the people I was scheduled to meet with lived through the war. Would they resent me for being American?

The answer was, to my relief, a resounding no. Everyone I talked to was warm and welcoming. You would have never known our countries were at war just decades earlier. But the visit made me realize how little I had seen or read about the Vietnamese perspective on the war.

In the years since that trip, I’ve tried to learn more about the Vietnamese experience. Most recently, I picked up The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen. I don’t usually reach for historical fiction, but when a good friend recommended it, I picked up a copy—and I’m glad I did.

The Sympathizer’s narrator—we never learn his name—is a communist double agent embedded with the South Vietnamese Army and their American allies. After he’s air-lifted out of the country during the fall of Saigon, he ends up in California spying on his fellow refugees and sending reports written in invisible ink to his handler back in Vietnam.

The story we’re reading is the narrator’s confession, which he is forced to write while held in a North Vietnamese reeducation camp. Much to the chagrin of the camp’s commandant, this confession makes it clear that the narrator is not a true believer in their cause. Instead, he “sympathizes” with people on both sides of the conflict.

For a novel that’s been met with such commercial success and critical acclaim (it won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction last year, and Nguyen recently received a MacArthur genius grant), it is surprisingly bleak. Nguyen doesn’t shy away from how traumatic the Vietnam War was for everyone involved. Nor does he pass judgment about where his narrator’s loyalties should lie. Most war stories are clear about which side you should root for—The Sympathizer doesn’t let the reader off the hook so easily.

More than 40 years later, many Americans still grapple with the big questions surrounding the Vietnam War: should we have gotten involved? Did our political and military leaders know what they were doing? Did they understand what the human cost of the war would be? (If you’re interested in reading more about this debate, I recommend H.R. McMaster’s excellent book Dereliction of Duty.)

Nguyen largely ignores these questions and instead tackles the role of individual morality in a time of war. The narrator commits horrible acts on behalf of the North Vietnamese government he serves and the refugee community he’s spying on. He plays both sides to survive. In the end, his lack of conviction makes him the most immoral character of all.

Despite how dark it is, The Sympathizer is still a fast-paced, entertaining read. I liked one particularly memorable section where the protagonist meets a famous Hollywood director and becomes a consultant for the Vietnam War epic he’s working on called The Hamlet. His attempts to bring the Vietnamese perspective into the film are thwarted at every turn by the director, who eventually grows so sick of the narrator that he may have tried to kill him with a stunt explosion gone wrong (the book doesn’t make it clear whether he did or not). If you’re a movie The Hamletbuff, you’ll notice that bears more than a passing resemblance to Apocalypse Now.

In an interview with NPR last year, Nguyen shared the story of the first time he saw Francis Ford Coppola’s classic film. He described watching a scene where American soldiers kill Vietnamese people as “the symbolic moment of my understanding that this was our place in an American war, that the Vietnam War was an American war from the American perspective and that, eventually, I would have to do something about that.” The Sympathizer offers a much-needed Vietnamese perspective on the war. I’m glad that it’s experienced such mainstream success, and I hope to read more books like it in the future.

Heart ache

A poetic novel about grief

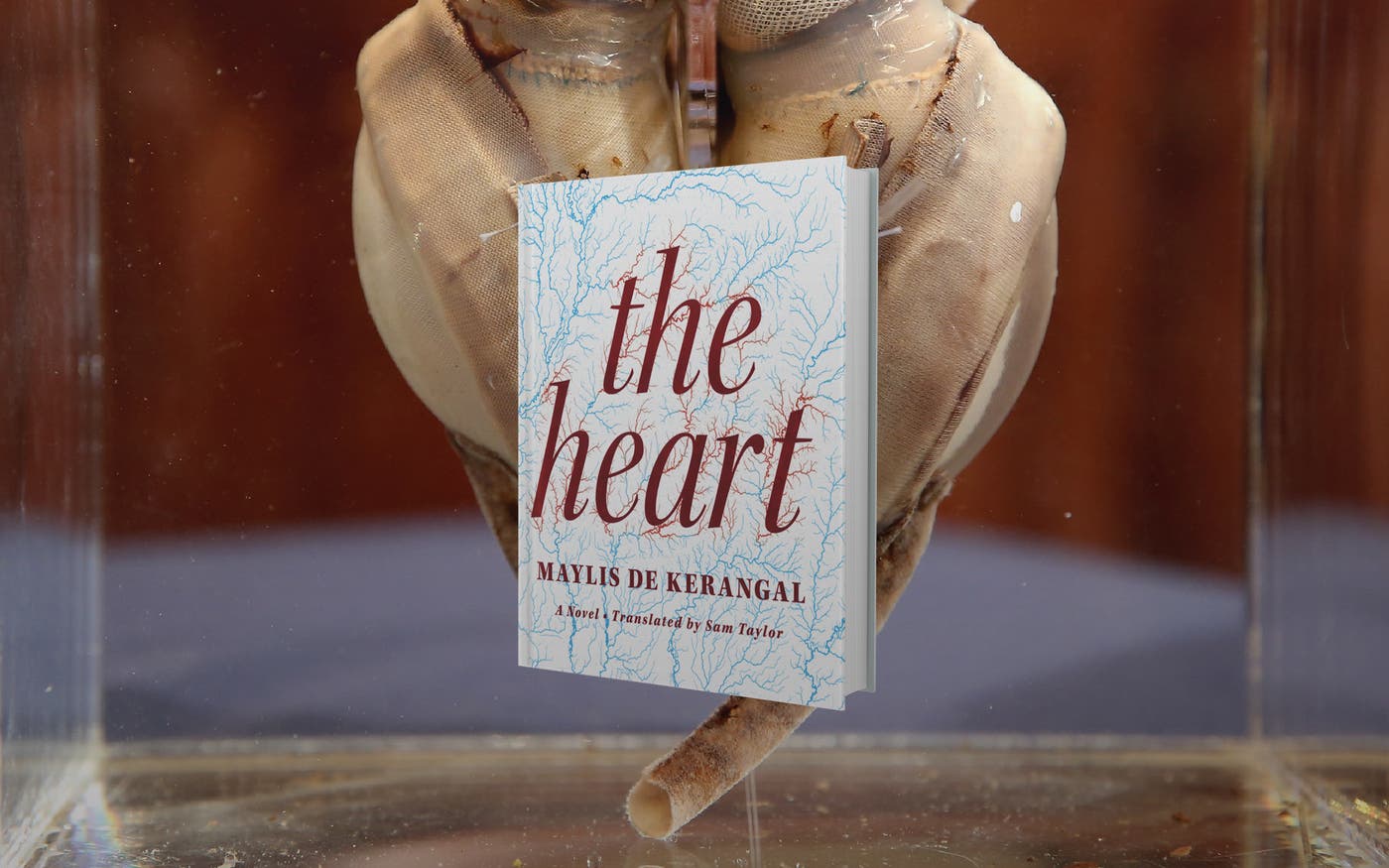

Melinda thought I would love Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart. She was right.

I recommend a lot of nonfiction books on Gates Notes, and every once in a while I review a novel. But I don’t think I’ve ever written about a book of poetry before. That’s almost what Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart is, though. It’s poetry disguised as a novel.

The story itself is simple: three French 20-year-olds go surfing in the middle of the night, and as they’re driving back from the beach just before sunrise they get in a car accident. Two of them survive but one of them, Simon, dies, and his parents have to decide whether to donate his heart or not. They decide to do it, and doctors transplant the heart, and the book is over. That’s it.

The car crash happens in the first 15 pages, so the rest of the book is a meditation on life, death, and, as the title suggests, the heart. There aren’t even that many characters: you meet Simon’s father and mother, the doctor on duty at the hospital when Simon gets there, the nurse assisting him, the head of the organ donation organization, the woman who gets the heart in the end, and a few other people.

But just describing the plot is like saying “during a heart transplant, doctors put one person’s heart into another person’s body” and leaving it at that. It’s not the plot that makes The Heart such a wonderful book. First of all, there’s the language. It makes me think of Vladimir Nabokov more than anybody else. The sentences are rich and full, and they go on and on, which is the exact opposite of how I write. There are sentences that last entire paragraphs.

At times I found myself reading more slowly than usual, simply because the way she describes things is so beautiful: at one point she describes a character’s words as “reddening rocks from a still-burning fire.” The word choices are very specific—I went to the dictionary a dozen times to look up words I didn’t know—but “rhizomic” turned out to be exactly what the passage needed.

The book connects you deeply with people who are only in the story for a few minutes. You get really detailed backstories about all the characters: Kerangal goes on for pages about the girlfriend of the surgeon who does the transplant, for example, even though you never meet that character. In the end, the effect is to remind you that all the people you meet in the novel— and all the people you meet every day, even if it’s just for a few seconds—have lives as full as yours.

And then there are the themes Kerangal is dealing with: grief most of all, and how it feels to have to change your life suddenly because somebody who was in it isn’t in it anymore. When I travel for the foundation, I meet parents whose children have died and children whose parents have died, and I get sad every time. This book forced me to feel the depth of that grief, and it was an experience I appreciated.

I told a friend the other day that she especially would like The Heart. Just like me, she mostly reads nonfiction, and this book is a good counterweight. When Melinda recommended the book to me, she said, “It’s different from most of the books you read.” And that’s true—but part of the reason for that is that it’s different from most books.

Different ≠ Less Than

The novel I gave to 50 friends

Graeme Simsion’s second Rosie book is just as smart, funny, and sweet as his first.

If somebody asked me, “what do you think your decades of working in technology have prepared you for?” my first answer definitely wouldn’t be, “writing a best-selling novel that beautifully explores the human condition.” But Australian author Graeme Simsion has taken his extensive experience in the data modeling industry and used it to do just that.

Melinda and I loved his first book, The Rosie Project. It starts when a geneticist who may or may not have Asperger’s Syndrome decides to put together a double-sided, 16-page questionnaire as the obvious first step to finding a wife. Ultimately the book is less about genetics or thinking too logically or the main character’s hilarious journey than it is about getting inside the mind and heart of someone a lot of people see as odd—and discovering that he isn’t really that different from anybody else.

Since then, I must have given The Rosie Project to at least 50 friends. Graeme has been busy too, writing a sequel called The Rosie Effect. As soon as we heard about it, Melinda and I asked him for an advance copy, and we enjoyed it so much that we invited Graeme to come to Seattle to talk to us about it.

I was happy to learn that one of my favorite things about both books is also one of Graeme’s favorite things. Usually, when we meet people who are different from us, in whatever way, we tend to treat them as inferior, even though we say that’s not what we’re doing. We may not even consciously realize we’re doing it. But through Don Tillman, the hero of both books, Graeme casts the issue in a different light. True, Don may not be the best at picking up on subtle social cues. But if you need to secretly collect DNA samples from 117 people at a party, there’s nobody in the world who’s going to do a better job. Different doesn’t mean less than.

What Don allows readers to appreciate is that, just because somebody might not be highly literate in the language of emotions doesn’t mean he doesn’t have emotions, and powerful ones at that. He sees the world in terms of logic, but he feels just as deeply about that world as everybody else. That puts him in a difficult position, and Graeme puts you right there with him.

The Rosie Effect, the second book, shows that Graeme isn’t a one-trick pony. It’s got a lot of the same characters, and of course they have the same foibles as they did in the first book. They even find themselves in some of the same kinds of situations. But somehow Graeme manages to make everything look and feel totally new. Don does aikido in the first book, and so when you get to aikido in the second book you think, is this just going to be the same thing again? But then it turns out to be funny in a completely different way.

The Rosie Effect, which will be released in the United States at the end of the year, improves on its predecessor in one interesting way. In the first book, you won’t necessarily see yourself in Don. (I’d say most readers will see somebody they know in him, but not necessarily themselves.) Anybody who’s a parent, though, has experienced what Don goes through in the second book. Am I doing this right? Because this isn’t what the pregnancy book says to do. Or this professional is judging me. What if she’s right and I’m wrong? Will my child be ruined? These are powerful fears we all have, and seeing them in Don makes you feel like you’re not the only one. And the outlandish plot—at one point Don decides the most logical thing to do is to have a New York accountant pretend to be an Italian peasant pretending to be a Columbia medical student—makes it impossible not to laugh at it all.

Graeme says that his comedy mentor’s mantra is, “Make ’em laugh. Make ’em cry. Make ’em think.” I think that with The Rosie Project and The Rosie Effect Graeme has written two books that would make his mentor proud.