Nuts and bolts

The start-ups making robots a reality

Here’s why I’m excited about the potential of robotics technology.

Is it harder for machines to mimic the way humans move or the way humans think? If you had asked me this question a decade ago, my answer would have been “think.” So much of how the brain works is still a mystery. And yet, in just the last year, advancements in artificial intelligence have resulted in computer programs that can create, calculate, process, understand, decide, recognize patterns, and continue learning in ways that resemble our own.

Building machines that operate like our bodies—that walk, jump, touch, hold, squeeze, grip, climb, slice, and reach like we do (or better)—would seem to be an easier feat in comparison. Surprisingly, it hasn’t been. Many robots still struggle to perform basic human tasks that require the dexterity, mobility, and cognition most of us take for granted.

But if we get the technology right, the uses for robots will be almost limitless: Robots can help during natural disasters when first responders would otherwise have to put their lives on the line—or during public health crises like the COVID pandemic, when in-person interactions might spread disease. On farms, they can be used instead of toxic chemical herbicides to manually pull weeds. They can work long days lugging hundred- or thousand-pound loads around factory floors. A good enough robotic arm will also be invaluable as a prosthesis.

I understand concerns about robots taking people’s jobs, an unfortunate consequence of almost every new innovation—including the internet, which (for example) turned everyone into a travel agent and eliminated much of the vacation-planning industry. If robots have a similar impact on employment, governments and the private sector will have to help people navigate the transition. But given present labor shortages in our economy and the dangerous or unrewarding nature of certain professions, I believe it’s less likely that robots replace us in jobs we love and more likely that they’ll do work people don’t want to be doing. In the process, they can make us safer, healthier, more productive, and even less lonely.

That’s why I’m so excited about the companies across the country and around the world that are at the forefront of robotics technology, working to usher in a robotics revolution. Some of their robots are humanoid or human-like—constructed so they can interact easily in environments built for people. Others have super-human traits like flight or extendable arms that can supplement an ordinary person’s abilities. Some move around on legs. Others have wheels. Some navigate using sensors. Others are operated by remote controls.

Despite their differences, though, one thing is certain: In healthcare, hospitality, agriculture, manufacturing, construction, and even our homes, robots have the potential to transform the way we live and work. In fact, a few of them already are.

Here are some of the cutting-edge robotics start-ups and labs that I’m excited about:

Agility Robotics

If we want robots to operate in our environments as seamlessly as possible, perhaps those robots should be modeled after people. That’s what Oregon-based Agility Robotics decided when creating Digit, what they call the “first human-centric, multi-purpose robot made for logistics work.” It’s roughly the same size as a person—it’s designed to work with people, go where we go, and operate in our workflows—but it’s able to carry much heavier loads and extend its “arms” to reach shelves we’d need ladders for.

Tevel

For farmers in some rich countries, around 40 percent of costs can come from labor—with workers spending entire days out in the hot sun and then stopping at night. But given the labor shortage in agriculture, farms often have to throw away fruit that’s not harvested in time. That’s why Tevel, founded in Tel Aviv, has created flying autonomous robots that can scan tree canopies and pick ripe apples and stone fruits around the clock, while simultaneously collecting comprehensive harvesting data in real time.

Apptronik

What’s more useful: multiple robots that can each do one task over and over, or one robot that can do multiple tasks and learn to do even more? To Apptronik, an Austin-based start-up that spun out of the human-centered robotics lab at the University of Texas, the answer is obvious. So they’re building “general-purpose” humanoid bi-pedal robots like Apollo, which can be programmed to do a wide array of tasks—from carrying boxes in a factory to helping out with household chores. And because it can run software from third parties, Apollo will be just a software update away from new functionalities.

RoMeLa

Building a robot that can navigate rocky and unstable terrain, and retain its balance without falling over, is no small task. But the Robotics and Mechanisms Lab, or RoMeLa, at UCLA is working on improving mobility for robots. They may have cracked the code with ARTEMIS, possibly the fastest “running” robot in the world that’s also difficult to destabilize. ARTEMIS actually competed at the RoboCup 2023, an international soccer competition held in France in July.

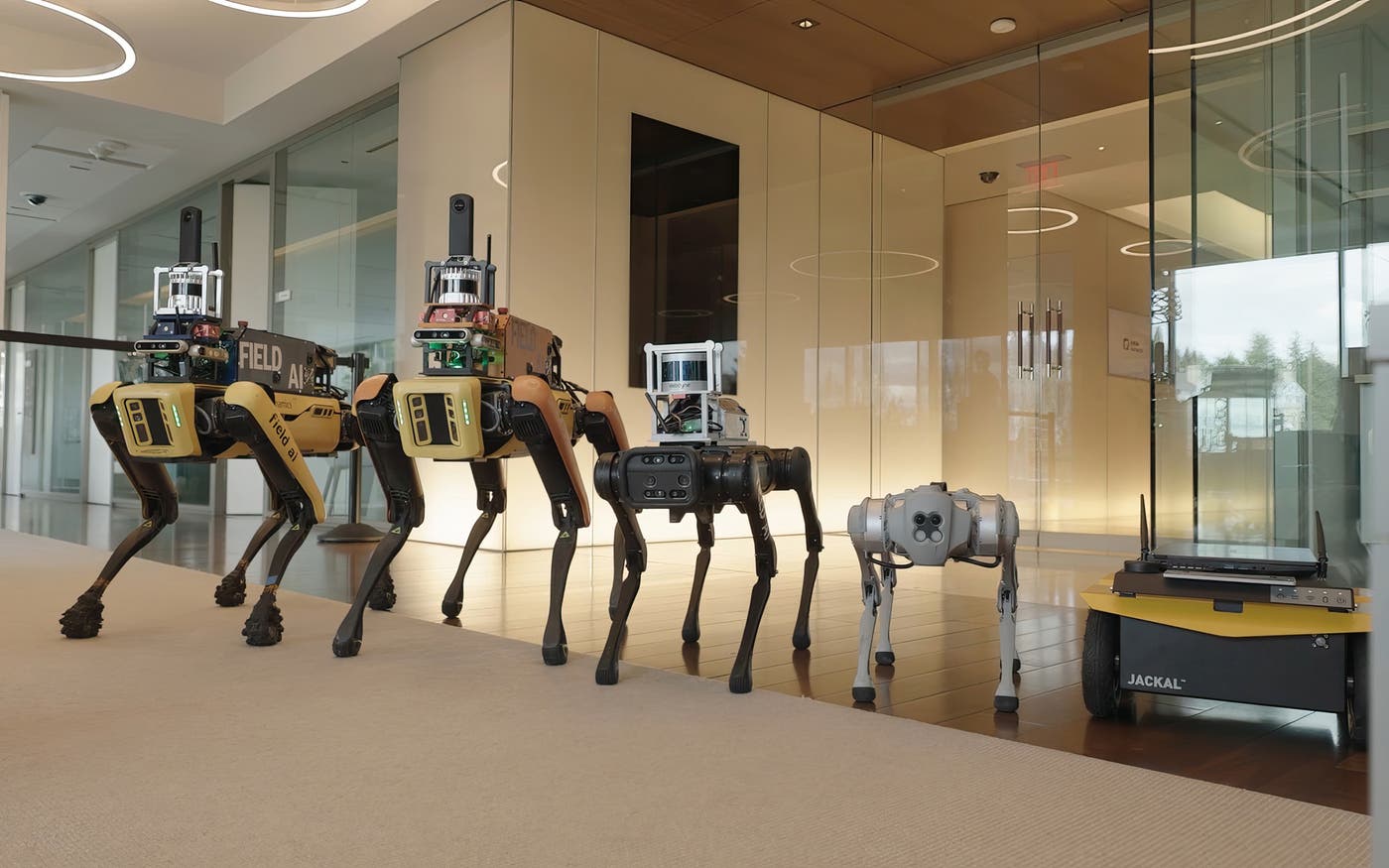

Field AI

Some robots don’t just need great “bodies”; they need great brains, too. That’s what Field AI—a robotics company based in Southern California that doesn’t build robots—is trying to create. Instead of focusing on the hardware of these machines, Field AI is developing AI software for other companies’ robots that enables them to perceive their environments, navigate without GPS (on land, by water, or in the air), and even communicate with each other.