The path forward

A map from classroom to career

A community college in California is streamlining the journey from high school to higher education to the workforce.

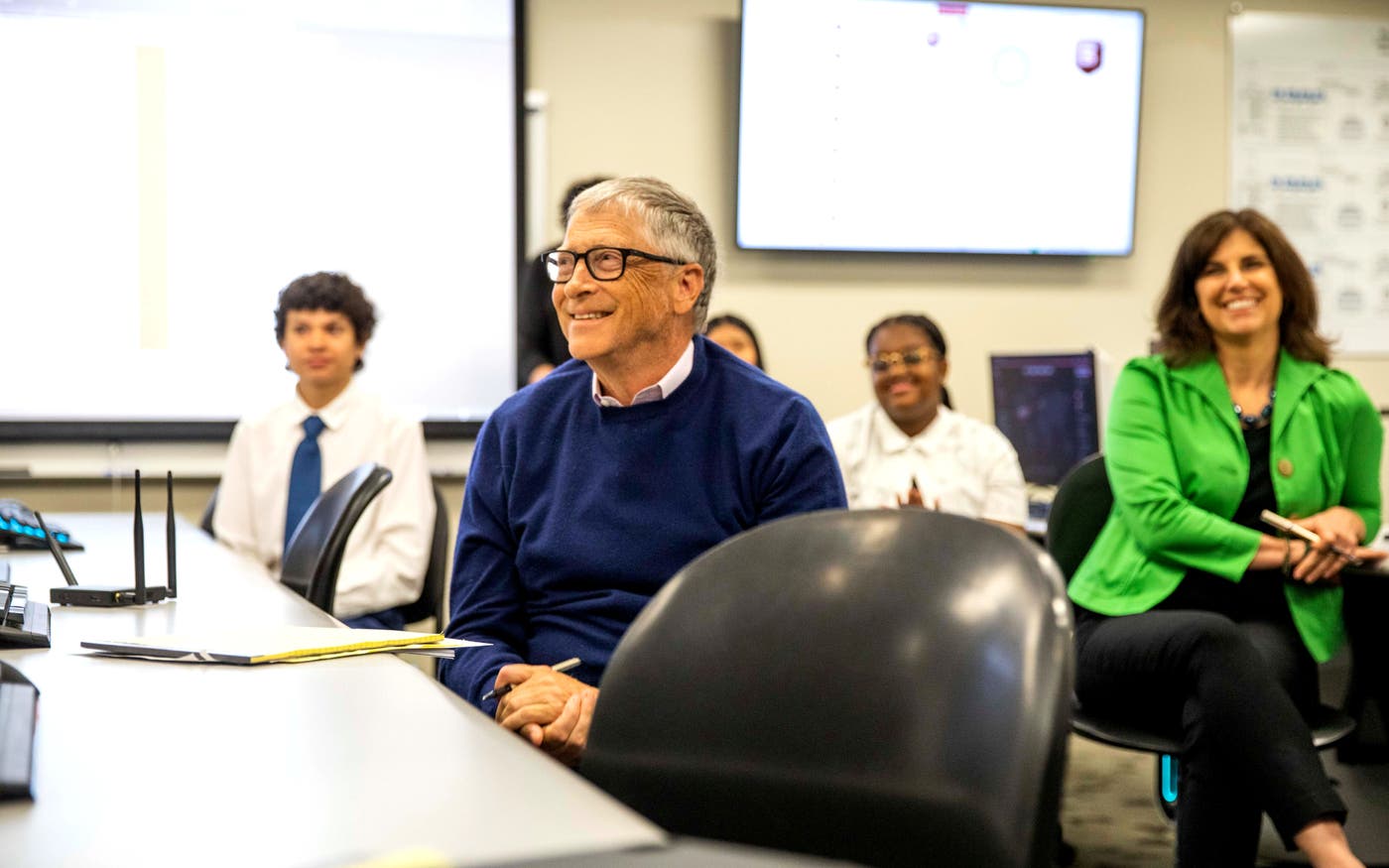

In April, I sat inside a computer lab at Chaffey College in Rancho Cucamonga, California and talked with students—some too young to drive—about cybersecurity. Many seemed as fascinated by technology as I’ve always been. One even taught himself to build computers during the pandemic. Despite their different backgrounds and ambitions, they were all there for the same reason: They’re part of the cybersecurity track, or pathway, at Chaffey.

If you spend time working on education in the United States, there’s a decent chance you’ll hear the word “pathways” tossed around. Most likely, you’ll hear it in discussions about the journey from high school to higher education to fulfilling career—a journey that, for many Black and Latino students and those from low-income backgrounds, is often anything but smooth. For a disproportionate percentage of them, it’s never completed. There are too many speed bumps, roadblocks, and detours along the way and not enough direction to guide them.

But integrated, intentionally-designed programs and structures that span K-12, college, and work can help, by creating high-quality pathways for students—from education to employment—that are seamless, structured, and commonsensical. That’s why pathways are the core of our education work at the Gates Foundation. We don’t just want students to graduate from high school. We don’t even just want them to complete college. We want to make sure they have paths to follow—and finish—from classroom to commencement to career that align with their interests, and to feel supported at every step along the way. That means addressing the transition points in the educational journey that often turn into those speed bumps, roadblocks, and detours.

At the Foundation, we believe there are four key components to creating these pathways. The first is providing quality advising to students that helps them identify the right college and career plan. The second is giving them access to (and credit for) college-level coursework—so they can see themselves as successful college students and save time and money getting that degree. The third is ensuring those credits are transferable between institutions and count toward their degrees. And the fourth is helping them have career-connected learning experiences, like project-based assignments, internships, and job shadows; that way, they can understand what it’s like to actually do the work they’re interested in, gain relevant skills and experience, and make connections in the field.

There are other organizations and initiatives that approach pathways differently. But the goal—for students to graduate with valuable credentials and transition successfully to the workforce—is the same.

And it’s becoming increasingly urgent. As I’ve written about before, by 2025 two thirds of all jobs in the United States will require some education beyond high school. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a lot of students to put off that postsecondary education; many had no other choice. But the data tells us that people who don’t start college within two years of getting their high school diplomas are less likely to persist and eventually get that postsecondary degree or credential. So the best way to get people graduating from college, so they can get the best jobs for themselves and make the most out of their careers, is to reach them early and ensure they have what they need to stay on the path.

That brings me back to my day in Rancho Cucamonga, where Chaffey has established pathways that align with the Foundation’s approach to providing the structure and support students need for the education they need to build a great career.

As a community college, Chaffey has an incredibly diverse student population that comes from largely underserved communities. Sixty-seven percent are Hispanic or Latino, eight percent are Black, and many are parents, veterans, and returning students. As one of Chaffey’s leaders, Dr. Laura Hope, put it, none of them are in the position to take an extended “vow of poverty” for the sake of education. While community colleges often emphasize exploration above all else, endless exploration that doesn’t result in skills, degrees, and jobs for students doesn’t actually serve students.

So Chaffey’s job is to help students first understand and then attain the credentials and degrees required, either to land a certain job or to transfer to a four-year college, as efficiently as possible.

As I saw firsthand, Chaffey’s pathways are increasingly focusing on just that. Rather than ask what people want to do with their careers—a mammoth question for both 18-year-olds and older students alike, and one that limits them only to professions they already know about—Chaffey’s advising program asks what they’re interested in, what their strengths are, what they care about, and, critically, how much time they have.

As a result, a student interested in technology who feels called to helping others might discover, for instance, that it’s cybersecurity—and not medicine—she wants to pursue. Then, Chaffey provides the student with a “map” that guides them and supplies them with all the information they need to succeed: the exact coursework they have to complete, the degree they need and can expect to attain (including both career-related certificates and associates degrees), the credits they can bring with them if they choose to transfer to a four-year university, the universities Chaffey has those matriculation agreements with, the jobs they’ll be qualified for upon completion, even the salary they can expect to earn. The school shows them there’s a path, and then helps shorten it.

But Chaffey doesn’t just show that path to “traditional” community college students. Through its dual enrollment program, which has grown from around 20 people to around 3,500 in the past four years, Chaffey is also reaching high school students and helping them find a path to post-secondary and professional success. I met some of them in the cybersecurity class I sat in on, and I was impressed by them, and by what Chaffey is doing for them. While dual enrollment programs that allow high school students to earn college credits exist throughout the United States, not enough schools encourage them to take courses that are intentionally designed to relate to their interests and expose them to potential future careers. Instead, students often end up attaining a random assortment of unrelated credits that are irrelevant to them later on. Chaffey’s pathways approach is one way to address this problem.

This benefits students at every age and stage of their educational journey in obvious ways, helping them avoid wasted credits—and wasted time and money. But it also benefits the economy, both locally in the Inland Empire region where Chaffey is located and statewide. When the school decided to become a leader in cybersecurity, one impetus was the region’s emerging cyber and tech industries, which were growing so fast that they couldn’t find enough qualified people to hire. With its cybersecurity pathway, Chaffey is filling a local need, serving as a regional economic engine, and preparing students for success in a field with around 72,000 job openings—many of them six-figure—in California alone. Thanks to internship opportunities with regional partners, also part of the pathways approach, some of the students I met already have jobs waiting for them once they graduate.

According to Dr. Hope, the number one thing colleges like Chaffey have to teach students is belief: belief in themselves, and belief that their education is really supporting them and setting them up for success. That’s easier said than done. But with a pathway to follow, students are less likely to feel lost and more likely to find their way—through school and to a fulfilling career. The more high-quality pathways we can create for them, the better.