Know your enemy

The U.S. military versus the mosquito

Finding ways to protect soldiers from mosquitoes is a top priority at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

The most dangerous foe U.S. soldiers may have ever encountered is the mosquito, which has caused more casualties than bombs or bullets during the nation’s conflicts.

One of the first military expenditures by the Continental Congress was $300 for quinine to protect General George Washington’s troops from malaria. During the Civil War, there were over a million cases of malaria in Union troops alone. In World War II, there were nearly 700,000 cases of malaria. In Vietnam, 50,000 cases. And more recently, of all the American soldiers deployed in Afghanistan, one out of every 20 of them battled malaria.

Finding ways to protect soldiers from the mosquito—the world’s deadliest animal—is a top priority at the U.S. Department of Defense’s Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR).

I expect most people have never heard about WRAIR—or, if they have, they may be confusing it with the more familiar but separate institution, the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where U.S. presidents visit wounded troops and go for medical treatment.

It’s too bad more people don’t know about the work being done at WRAIR. Since its founding in 1893, WRAIR has been a global research leader into new malaria drugs, mosquito control, and more recently, vaccines, to protect people from mosquito-borne diseases. This research benefits the lives of not only American soldiers, but also billions of people living in areas where mosquito-borne diseases are a threat. That’s why our foundation collaborates with WRAIR on a range of research projects in malaria and other diseases that endanger the lives of people living in some of the world’s poorest areas.

Here’s one of many incredible facts that speak to WRAIR prominence in malaria research: WRAIR has contributed to the discovery and development of all FDA-approved malaria drugs, including primaquine, mefloquine, atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone), tafenoquine, and doxycycline. If you’ve ever traveled to an area where malaria is prevalent you’ve probably been prescribed one of these drugs for protection. And because of the spread of malaria drug resistance, WRAIR continues to explore new drugs to stay one step ahead of this threat.

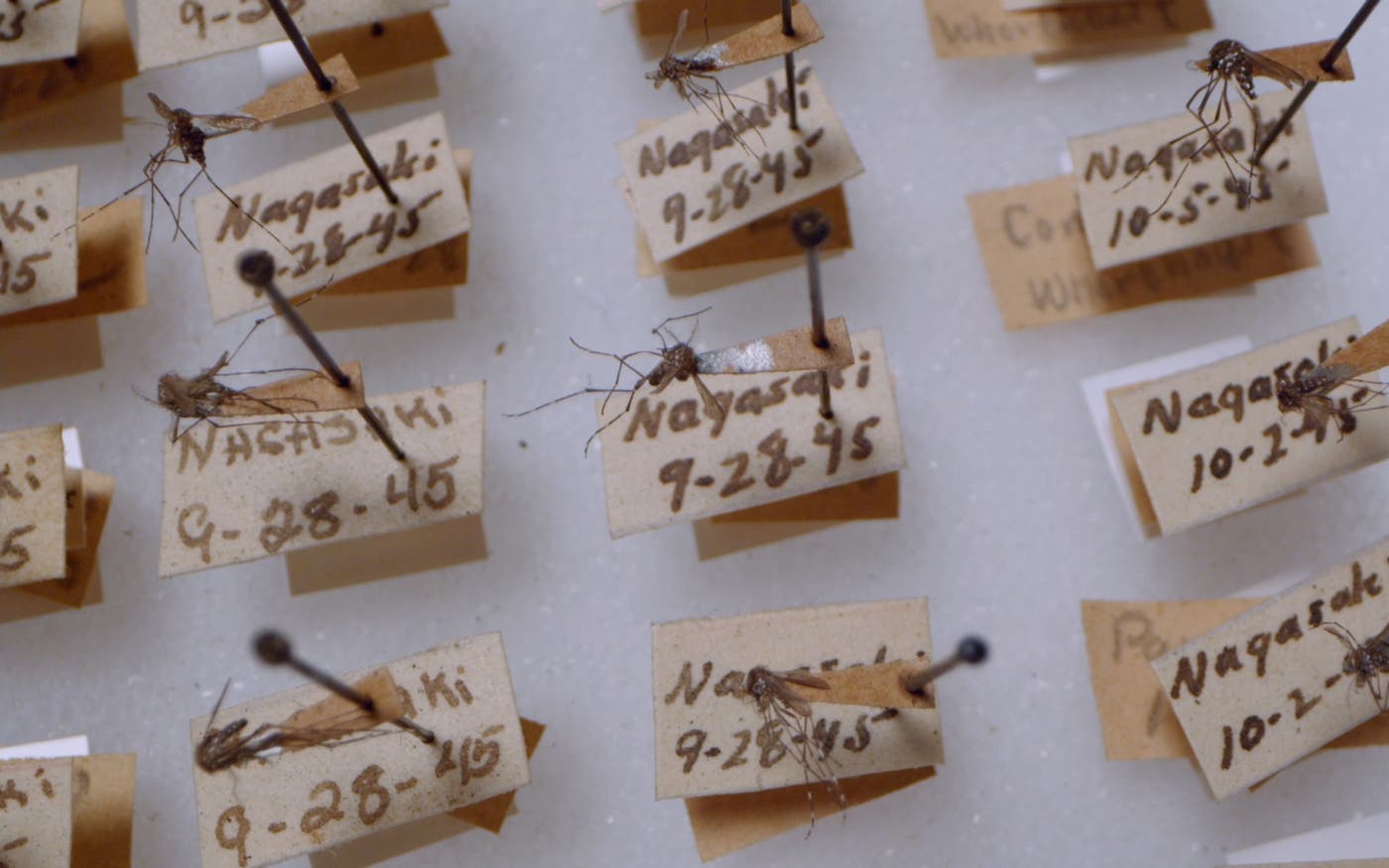

WRAIR, in partnership with the Smithsonian Institute, also manages the world’s largest mosquito collection, which currently has more than 1.7 million specimens. Some of the oldest were collected by Walter Reed, the Army major who helped discover that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes. WRAIR is named in his honor.

This large mosquito collection allows WRAIR researchers to “know their enemy,” by giving them a deep understanding of the huge variety of mosquito species that populate the globe so they can mount the most effective defenses against them.

The first line of defense for soldiers is their clothing and WRAIR has developed uniforms treated with insecticides to protect them. Then, there are mosquito nets and various repellents, including ones that double as camouflage paint.

Highly effective vaccines against malaria and other mosquito-borne disease are also a priority at WRAIR. WRAIR developed the first-ever malaria vaccine in conjunction with GlaxoSmithKline. Researchers at WRAIR also led the development of a Zika vaccine.

One of the most surprising and important areas of research at WRAIR are the human malaria infection challenge trials. As part of this program, WRAIR recruits volunteers who agree to be bitten by malaria-infected mosquitoes, exposing themselves to a curable form of the disease to test the effectiveness of various interventions. This might sound scary, but the trials are extremely safe. The volunteers are carefully monitored and are quickly cured before they become too ill. In the last 30 years, WRAIR has performed over 100 trials on over 2,200 volunteers. Thanks to this research, WRAIR has greatly accelerated the development of experimental vaccines and malaria drugs.

What’s most exciting at WRAIR is the research that will help us all prepare for the threats of the future, including climate change, which will increase the spread of mosquito-borne diseases.

As Col. Brian Evans, WRAIR’s chief entomologist, says, “The challenge is always evolving and the role of WRAIR is to keep up with that, to stay ahead of the game.”

Thanks to their incredible work for more than 125 years, WRAIR has done just that.