Bite back

Great news for mosquito haters

With some breakthrough tools, the end of malaria could be here soon.

I was scrolling Reddit recently when I saw a video of a mosquito trying and failing to suck someone’s blood. Some of the replies were pretty funny, but I noticed that most of them were just some form of “How do I get this person’s superpower?” It was a great reminder of how universally hated these bloodsuckers are.

But I have good news—for Reddit users and everyone else: Real progress has been made in the fight against mosquitoes and specifically against malaria, the deadliest disease they carry. And I believe we’ll soon have the transformational tools needed to end malaria entirely.

Eradication is a goal Melinda and I set back in 2007, when we stood before a group of global health leaders and called for something many considered impossible: wiping malaria out completely from every country. And until that happened, our goal was—and is—to save as many lives as possible by maximizing the impact of the tools we already have. Eradicating the disease wasn't a new idea; the World Health Organization had made a similar declaration back in 1955. But that earlier campaign, while successful in many wealthier parts of the world, had fallen short across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Oceania. Despite half a century of effort, malaria was still infecting up to half a billion people—and claiming a million lives—annually.

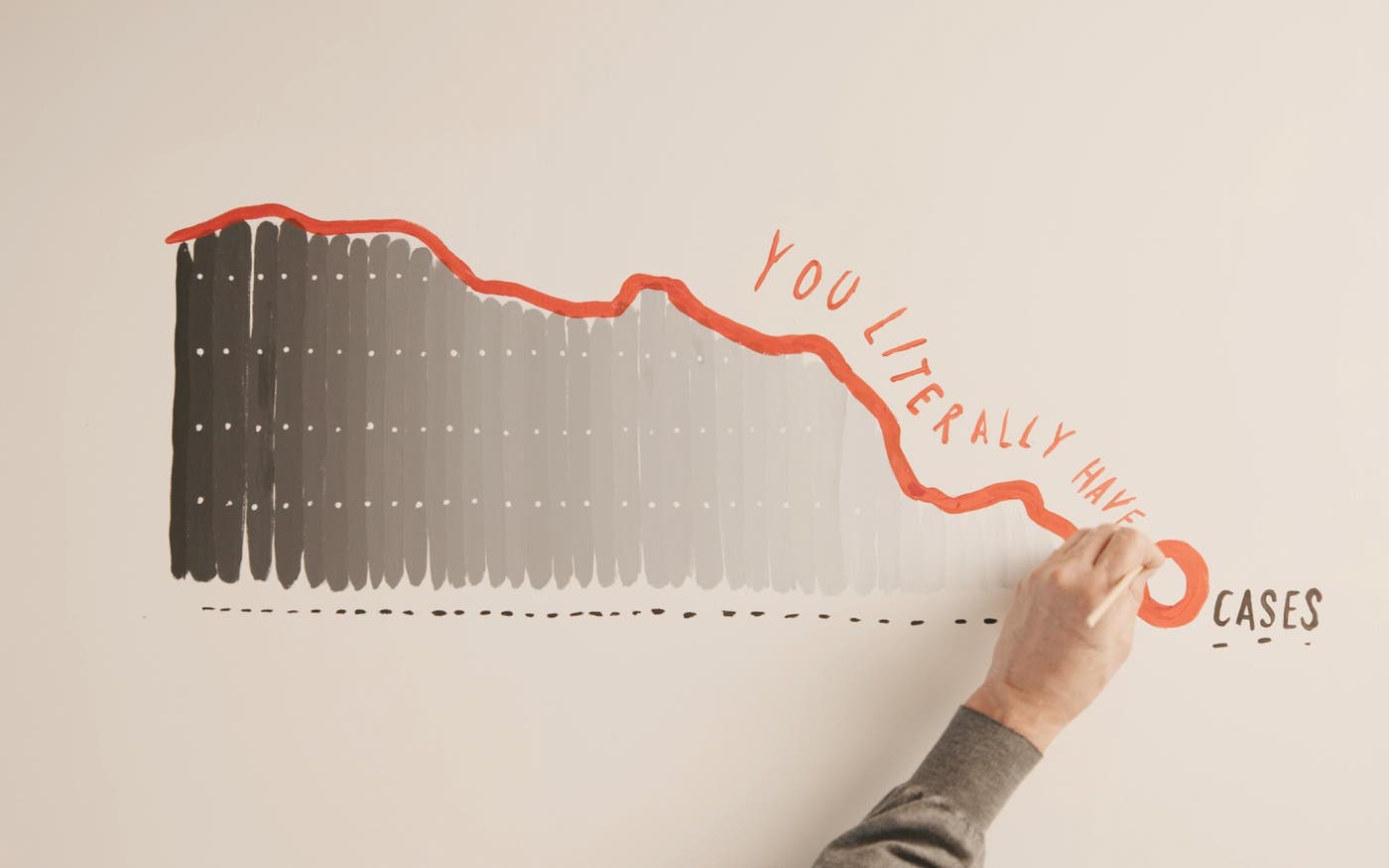

Today, the landscape has changed dramatically. In 2022—the last year we have data on—there were 249 million cases worldwide and 608,000 deaths. Those are staggering numbers, but they’re also improvements from where the world was back in 2007. Since then, 17 additional countries have been declared malaria-free by the World Health Organization. Outside of Africa, deaths from the disease have mostly been eliminated.