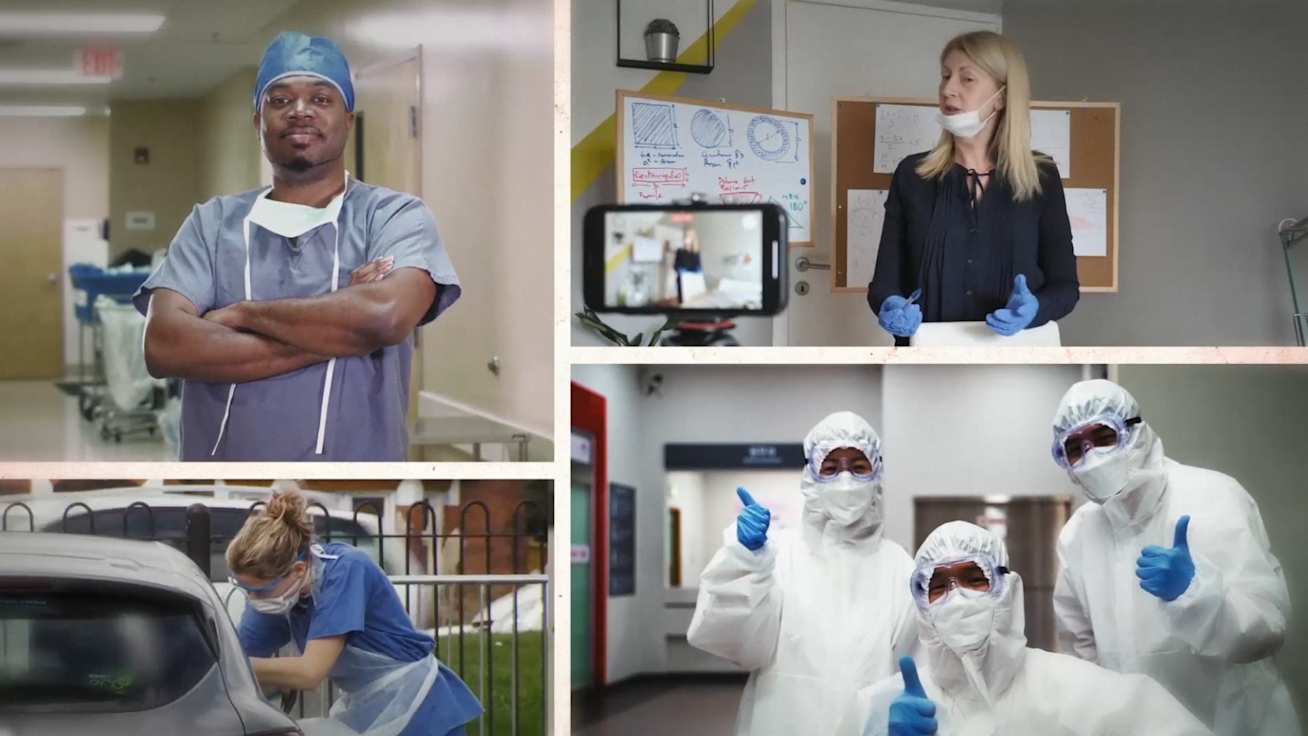

Inspiring acts

7 unsung heroes of the pandemic

Incredible people caring for those in need during COVID-19.

When I was a kid, my image of a hero was largely inspired by my dad’s collection of early Superman comics. I read them all. A “hero” was somebody who had supernatural powers like flying, laser vision, or the strength to bend steel.

As humans, of course, we’re all pretty limited in our physical powers. We don’t fly. We can’t see through walls. But what’s unbounded in us is our ability to see injustices and to take them on—often at great risk to ourselves.

My work in global health and development has introduced me to many extraordinary heroes with this kind of superpower. And I’ve had the honor of highlighting many of them on this blog: An epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox. A doctor working to end sexual violence in Africa. A researcher working to end hunger with improved crops. Just to name a few.

Why do we need heroes?

Because they represent the best of who we can be. Their efforts to solve the world’s challenges demonstrate our values as a society and they serve as powerful examples of how to make a positive difference in the world. And if enough people hear about their actions, they can inspire others to do something heroic too.

If there’s ever been a time that we need heroes, it’s now. The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented health and economic challenges, especially for the most vulnerable among us. The good news is that many people from all walks of life are doing their part to help them. Health care workers. Scientists. Firefighters. Grocery store workers. Aid workers. Vaccine trial participants. And ordinary citizens caring for their neighbors.

Here are portraits of a few individuals from around the world working to alleviate suffering during this pandemic. I hope their stories inspire you just as much as they have me.

To these heroes and heroes everywhere, thank you for the work you do!