Starting line

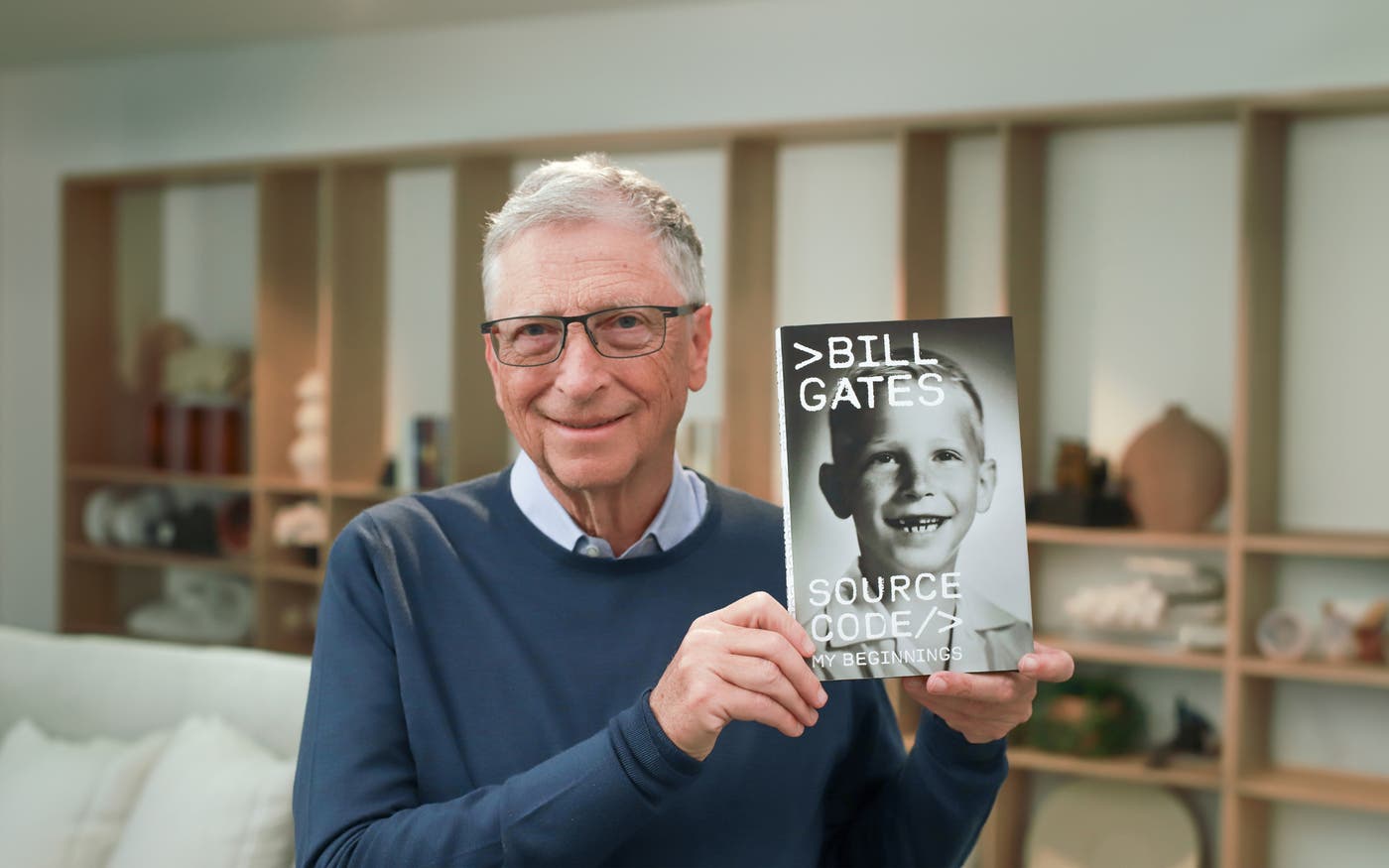

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

Endgame

Let’s make this the last pandemic

My new book is all about how we eliminate the pandemic as a threat to humanity.

The great epidemiologist Larry Brilliant once said that “outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional.” I thought about this quote and what it reveals about the COVID-19 pandemic often while I was working on my new book.

On the one hand, it’s disheartening to imagine how much loss and suffering could’ve been avoided if we’d only made better choices. We are now more than two years into the pandemic. The world did not prioritize global health until it was too late, and the result has been catastrophic. Countries failed to prepare for pandemics, rich countries reduced funding for R&D, and most governments failed to strengthen their health systems. Although we’re finally reaching the light at the end of the tunnel, COVID still kills several thousand people every day.

On the other hand, Dr. Brilliant’s quote makes me feel hopeful. No one wants to live through this again—and we don’t have to. Outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional. The world doesn’t need to live in fear of the next pandemic. If we make key investments that benefit everyone, COVID-19 could be the last pandemic ever.

This idea is what my book, How to Prevent the Next Pandemic , is all about. I’ve been part of the effort to stop COVID since the early days of the outbreak, working together with experts from inside and out of the Gates Foundation who have been fighting infectious diseases for decades. I’m excited to share what I've learned along the way, because our experience with COVID gives us a clear pathway for how to be ready next time.

So, how do we do it? In my book, I explain the steps we need to take to get ready. Together, they add up to a plan for eliminating the pandemic as a threat to humanity. These steps—alongside the remarkable progress we’ve already made over the last two years in creating new tools and understanding infectious diseases—will reduce the chance that anyone has to live through another COVID.

Imagine a scenario like this: A concerning outbreak is rapidly identified by local public health agencies, which function effectively in even the world’s poorest countries. Anything out of the ordinary is shared with scientists for study, and the information is uploaded to a global database monitored by a dedicated team.

If a threat is detected, governments sound the alarm and initiate public recommendations for travel, social distancing, and emergency planning. They start using the blunt tools that are already on hand, such as quarantines, antivirals that protect against almost any strain, and tests that can be performed anywhere.

If this isn’t sufficient, then the world’s innovators immediately get to work developing new tests, treatments, and vaccines. Diagnostics in particular ramp up extremely fast so that large numbers of people can be tested in a short time. New drugs and vaccines are approved quickly, because we’ve agreed ahead of time on how to run trials safely and share the results. Once they’re ready to go into production, manufacturing gears up right away because factories are already in place and approved.

No one gets left behind, because we’ve already worked out how to rapidly make enough vaccines for everyone. Everything gets where it’s supposed to, when it’s supposed to, because we’ve set up systems to get products delivered all the way to the patient. Communications about the situation are clear and avoid panic.

And this all happens quickly. The goal is to contain outbreaks within the first 100 days before they ever have the chance to spread around the world. If we had stopped the COVID pandemic before 100 days, we could’ve saved over 98 percent of the lives lost.

I hope people who read the book come away with a sense that ending the threat of pandemics forever is a realistic, achievable, and essential goal. I believe this is something that everyone—whether you’re an epidemiologist, a policymaker, or just someone who’s exhausted from the last two years–should care about.

The best part is we have an opportunity to not just stop things from getting worse but to make them better. Even when we’re not facing an active outbreak, the steps we can take to prevent the next pandemic will also make people healthier, save lives, and shrink the health gap between the rich and the poor. The tools that stop an outbreak can also help us find and treat more HIV cases. They can protect more children from deadly diseases like malaria, and they can give more people around the world access to high quality care.

Shrinking the health gap was the life’s work of my friend Paul Farmer, who tragically died in his sleep in February. That’s why I’m dedicating my proceeds from this book to his organization Partners in Health, which provides amazing health care to people in some of the poorest countries in the world. I will miss Paul deeply, but I am comforted by the knowledge that his influence will be felt for decades to come.

If there’s one thing the world has learned over the last two years, it’s that we can’t keep living with the threat of another variant—or another pathogen—hanging over our heads. This is a pivotal moment. There is more momentum than ever before to stop pandemics forever. No one who lived through COVID will ever forget it. Just like a war can change the way a generation looks at the world, COVID has changed the way we see the world.

Although it may not always feel like it, we have made tremendous progress over the last two years. New tools will let us respond faster next time, and new capabilities have made us better prepared to fight deadly pathogens. The world wasn’t ready for COVID, but we can choose to be ready next time.

Just 230 pages

My new climate book is finally here

Everything you need to know about avoiding the worst climate outcomes.

When I worked at Microsoft, it was always a thrill to see a product we’d been working on for years finally get released to the public. I’m feeling the same sense of anticipation today. My new book on climate change is available now online and in bookstores.

I wrote How to Avoid a Climate Disaster because I think we’re at a crucial moment. I’ve seen exciting progress in the more than 15 years that I’ve been learning about energy and climate change. The cost of renewable energy from the sun and wind has dropped dramatically. There’s more public support for taking big steps to avoid a climate disaster than ever before. And governments and companies around the world are setting ambitious goals for reducing emissions.

What we need now is a plan that turns all this momentum into practical steps to achieve our big goals. That’s what How to Avoid a Climate Disaster is: a plan for eliminating greenhouse gas emissions.

I kept the jargon to a minimum because I wanted the book to be accessible to everyone who cares about this issue. I didn’t assume that readers know anything about energy or climate change, though if you do, I hope it will deepen your understanding of this incredibly complex topic. I also included ways in which everyone can contribute—whether you’re a political leader, an entrepreneur, an inventor, a voter, or an individual who wants to know how you can help.

The effort I founded called Breakthrough Energy, which started with a venture fund to invest in promising clean energy companies, has expanded to a network of philanthropic programs, investment funds, and advocacy efforts to accelerate energy innovation at every step. We’ll be supporting great thinkers and cutting-edge technologies and businesses, as well as pushing for public- and private-sector policies that will speed up the clean energy transition. Over the coming weeks and months, we’ll be turning the ideas in my book into action and trying to turn this plan into reality.

Below is an excerpt from the introduction, which gives you a sense of what the book is about and how I came to write it. I hope you’ll check out the book, but much more important, I hope you’ll do what you can to help us keep the planet livable for generations to come.

Excerpt from How to Avoid a Climate Disaster

Two decades ago, I would never have predicted that one day I would be talking in public about climate change, much less writing a book about it. My background is in software, not climate science, and these days my full-time job is working with my wife, Melinda, at the Gates Foundation, where we are super-focused on global health, development, and U.S. education.

I came to focus on climate change in an indirect way—through the problem of energy poverty.

In the early 2000s, when our foundation was just starting out, I began traveling to low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia so I could learn more about child mortality, HIV, and the other big problems we were working on. But my mind was not always on diseases. I would fly into major cities, look out the window, and think, Why is it so dark out there? Where are all the lights I’d see if this were New York, Paris, or Beijing?

I learned that about a billion people didn’t have reliable access to electricity and that half of them lived in sub-Saharan Africa. (The picture has improved a bit since then; today roughly 860 million people don’t have electricity.) I began to think about how the world could make energy affordable and reliable for the poor. It didn’t make sense for our foundation to take on this huge problem—we needed it to stay focused on its core mission—but I started kicking around ideas with some inventor friends of mine.

In late 2006 I met with two former Microsoft colleagues who were starting nonprofits focused on energy and climate. They brought along two climate scientists who were well versed in the issues, and the four of them showed me the data connecting greenhouse gas emissions to climate change.

I knew that greenhouse gases were making the temperature rise, but I had assumed that there were cyclical variations or other factors that would naturally prevent a true climate disaster. And it was hard to accept that as long as humans kept emitting any amount of greenhouse gases, temperatures would keep going up.

I went back to the group several times with follow-up questions. Eventually it sank in. The world needs to provide more energy so the poorest can thrive, but we need to provide that energy without releasing any more greenhouse gases.

Now the problem seemed even harder. It wasn’t enough to deliver cheap, reliable energy for the poor. It also had to be clean.

Within a few years, I had become convinced of three things:

- To avoid a climate disaster, we have to get to zero greenhouse gas emissions.

- We need to deploy the tools we already have, like solar and wind, faster and smarter.

- And we need to create and roll out breakthrough technologies that can take us the rest of the way.

The case for zero was, and is, rock solid. Setting a goal to only reduce our emissions—but not eliminate them—won’t do it. The only sensible goal is zero.

This book suggests a way forward, a series of steps we can take to give ourselves the best chance to avoid a climate disaster. It breaks down into five parts:

Why zero? In chapter 1, I’ll explain more about why we need to get to zero, including what we know (and what we don’t) about how rising temperatures will affect people around the world.

The bad news: Getting to zero will be really hard. Because every plan to achieve anything starts with a realistic assessment of the barriers that stand in your way, in chapter 2 we’ll take a moment to consider the challenges we’re up against.

How to have an informed conversation about climate change. In chapter 3, I’ll cut through some of the confusing statistics you might have heard and share the handful of questions I keep in mind in every conversation I have about climate change. They have kept me from going wrong more times than I can count, and I hope they will do the same for you.

The good news: We can do it. In chapters 4 through 9, I’ll break down the areas where today’s technology can help and where we need breakthroughs. This will be the longest part of the book, because there’s so much to cover. We have some solutions we need to deploy in a big way now, and we also need a lot of innovations to be developed and spread around the world in the next few decades.

Steps we can take now. I wrote this book because I see not just the problem of climate change; I also see an opportunity to solve it. That’s not pie-in-the-sky optimism. We already have two of the three things you need to accomplish any major undertaking. First, we have ambition, thanks to the passion of a growing global movement led by young people who are deeply concerned about climate change. Second, we have big goals for solving the problem as more national and local leaders around the world commit to doing their part.

Now we need the third component: a concrete plan to achieve our goals.

Just as our ambitions have been driven by an appreciation for climate science, any practical plan for reducing emissions has to be driven by other disciplines: physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, political science, economics, finance, and more. So in the final chapters of this book, I’ll propose a plan based on guidance I’ve gotten from experts in all these disciplines. In chapters 10 and 11, I’ll focus on policies that governments can adopt; in chapter 12, I’ll suggest steps that each of us can take to help the world get to zero. Whether you’re a government leader, an entrepreneur, or a voter with a busy life and too little free time (or all of the above), there are things you can do to help avoid a climate disaster.

That’s it. Let’s get started.

Rear view mirror

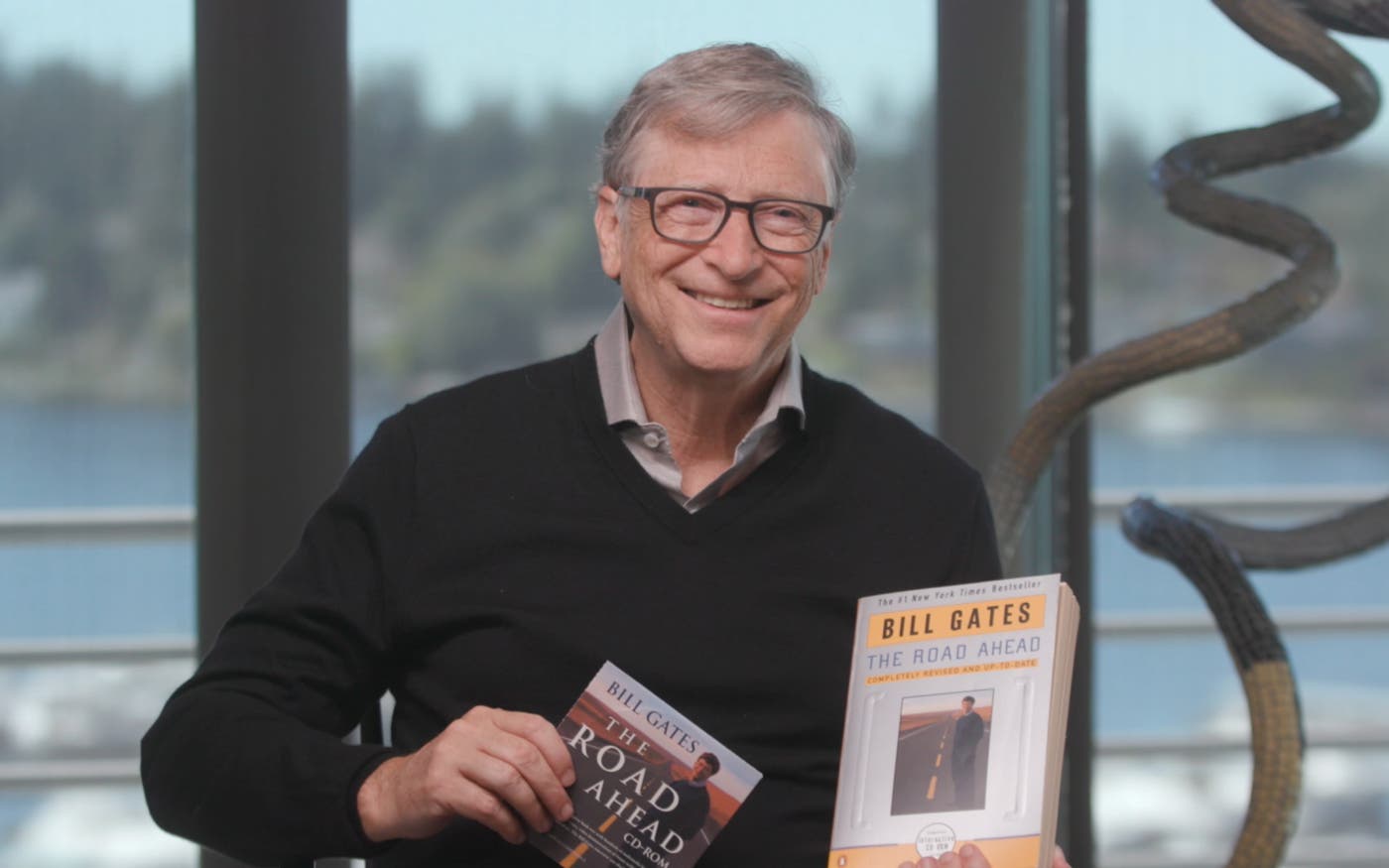

The Road Ahead after 25 years

The predictions I got right and wrong in my first book.

Twenty-five years ago today, I published my first book, The Road Ahead. At the time, people were wondering where digital technology was headed and how it would affect our lives, and I wanted to share my thoughts—and my enthusiasm. I also had fun making some predictions about breakthroughs in computing, and especially the Internet, that were coming in the next couple of decades.

Next February, I’ll release another book, this one about climate change. Before it hits the shelves, I thought it would be fun to look back at The Road Ahead and see how things turned out.

As I wrote in The Road Ahead, we tend to overestimate the changes that will happen in the short term and underestimate the ones that will happen over the long term. That is certainly my experience with the book itself. I was too optimistic about some things, but other things happened even faster or more dramatically than I imagined.

These days, it’s easy to forget just how much the Internet has transformed society. When The Road Ahead came out, people were still navigating with paper maps. They listened to music on CDs. Photos were developed in labs. If you needed a gift idea, you asked a friend (in person or over the phone). Today you can do every one of these things much more easily—and in most cases at a much lower cost too—using digital tools.

That’s all covered in the book (I was thinking and learning about these things obsessively back then). For instance, there’s a chapter on video on demand and computers that will fit in your pocket. You can download it here for free:

One thing I was probably too optimistic about is the rise of digital agents. It is true that we have Cortana, Siri, and Alexa, but working with them is still far from the rich experience I had in mind in 1995. They don’t yet “learn about your requirements and preferences in much the way that a human assistant does,” as I wrote at the time. We’re just at the beginning of what agents will eventually be capable of.

Another idea that’s central to The Road Ahead—that technology would allow unprecedented social networking—has pretty much come to pass. I am surprised, though, by the way social networks are both bringing us together and contributing to a more polarized atmosphere. I didn’t anticipate how much people would choose to filter out different perspectives and harden their own views.

One thing I wrote about that hasn’t happened yet—but I still think will happen—is the way the Internet will affect the structure of our cities. Today the cost of living in a dense downtown, like Seattle’s, is so high that many workers (including teachers, police officers, and baristas) can’t afford to live there. Even high earners spend a disproportionate percentage of their income on rent. As a result, some cities are arguably too successful, and others are not successful enough. It’s a real problem for our country.

But as digital technology makes it easier to work at home, then you can commute less often. That, in turn, makes it more attractive to live father away from the office, where you can afford a bigger house than in the city center. It also reduces the number of cars on the road at any given time. Over time, these shifts would mean major changes in the ways our cities work and are built.

We’re starting to see some of these effects come into play now, as office workers stay home because of COVID-19. Microsoft recently announced a policy recognizing that doing some work from home (for less than 50 percent of the time) will be standard even after the pandemic is over and their offices open back up. I think this trend will accelerate in the coming years.

The Road Ahead has a lot in common with my new book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster. Both are about how technology and innovation can help solve important problems. Both share glimpses into the cutting-edge technology I get to learn about.

One thing is different: The stakes are higher with climate change. As passionate as I am about software, the effort to avoid a climate disaster has a whole other level of urgency. Failing to get this right will have bad consequences for humanity. But you can also see the glass as half full. There are huge opportunities to solve this problem, eliminate our greenhouse gas emissions, and create new industries that make clean energy available and affordable for everyone—including people in the world’s poorest countries.

I’m excited to get the new book out there and continue the conversation about how to keep the planet livable for everyone.