Berkshire beds

Testing mattresses with Warren Buffett

Our visit to Omaha’s 80-acre furniture store.

When the weather turns warm, some people head to the beach. Some like a picnic in the park. Personally, there is one place I visit every spring no matter what: Omaha, Nebraska, the site of Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholders weekend with the company’s CEO and chairman (and my friend) Warren Buffett.

“Woodstock for Capitalists” is always a magical weekend, and this year’s was no exception. Tens of thousands of people came to buy stuff from Berkshire companies, check out the local steakhouses, and most of all, soak up the wit and wisdom of Warren and his partner, Charlie Munger. I would go even if I weren’t on the company’s board of directors. Despite all the changes in the business landscape during Warren’s 52-year tenure, he has lived by the same principles of integrity and creating business value since day one. He sets a wonderful example, and even though I have known him well for more than 25 years, I have never stopped learning from him.

Although the Berkshire weekend is always busy, Warren and I usually find time to goof off with a few games of bridge or a golf-cart ride around the showroom. (See my posts from 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. I didn’t post anything last year, but we goofed off then too.)

This year, Warren took me on a tour of Nebraska Furniture Mart, a super-successful megastore owned by Berkshire. We tried out some lounge chairs, played with remote-controlled mattresses, and somehow managed to get lost. Take a look:

Starting line

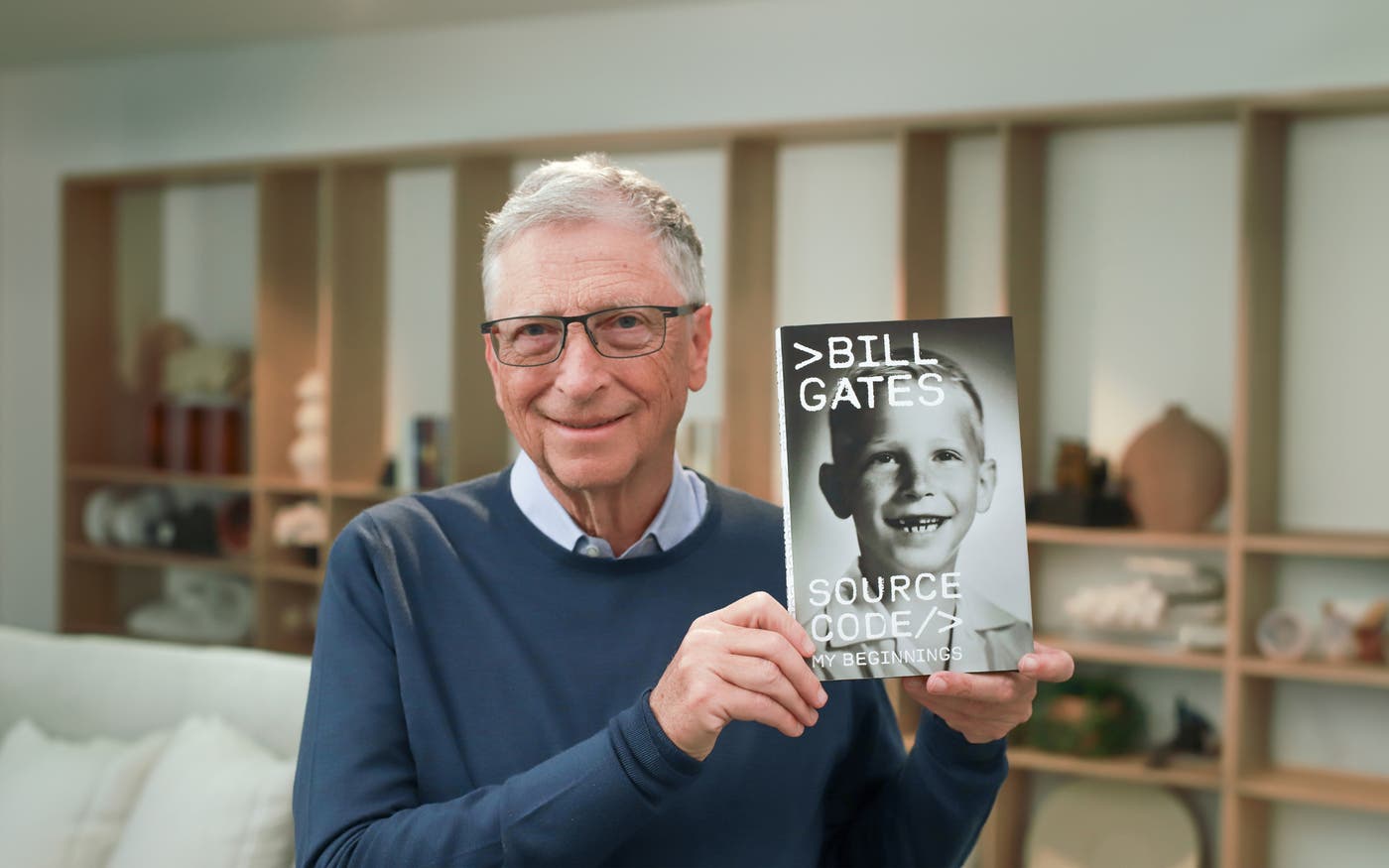

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

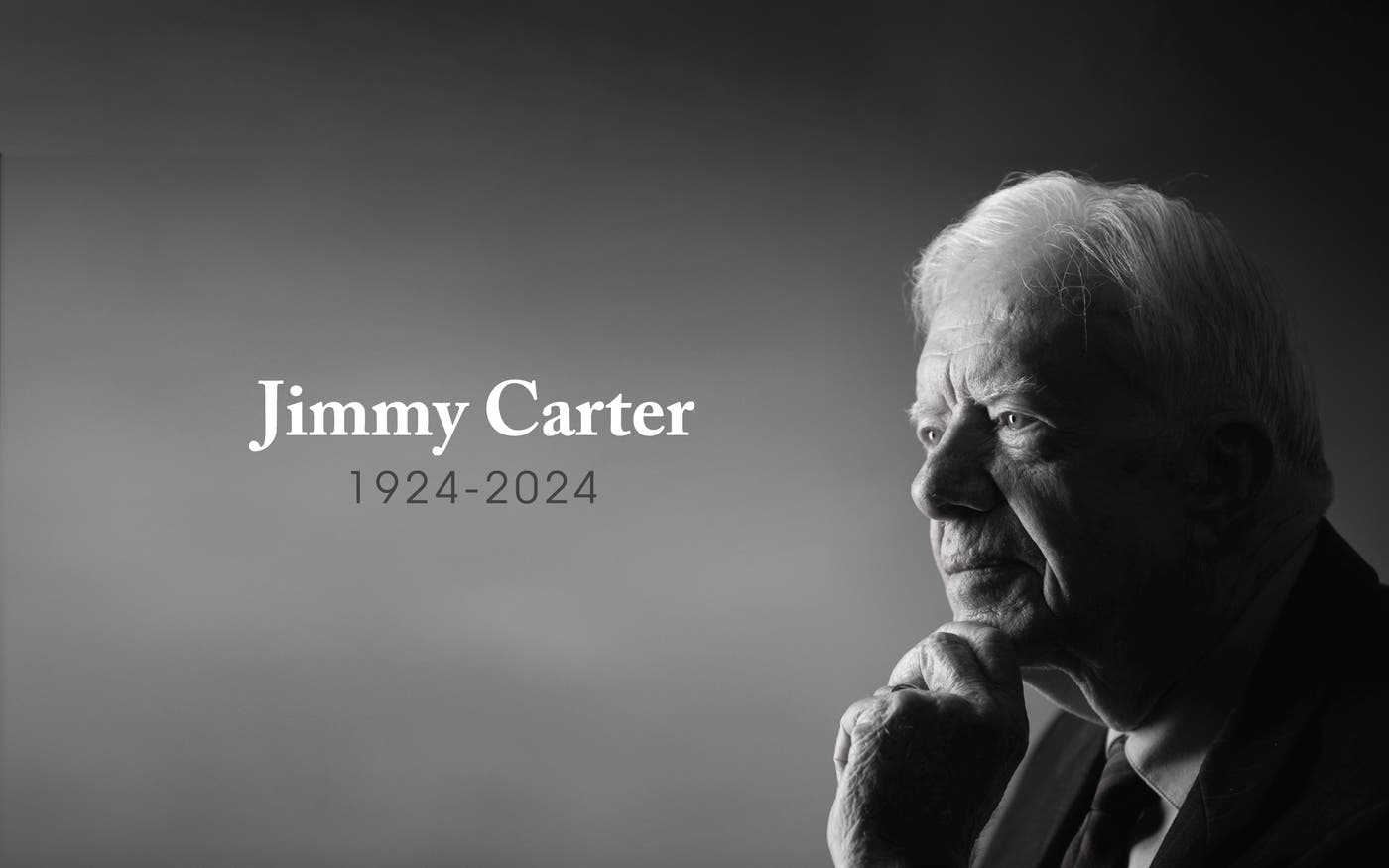

Moral center

My fondest memories of Jimmy Carter

He and Rosalynn were among my first and most inspiring role models in global health.

I am deeply saddened to learn of the passing of former president Jimmy Carter, and my heart is heavy for the whole Carter family. For more than two decades, I’ve had a chance to work with Jimmy, Rosalynn, and the Carter Center on several global health efforts, including our mutual work to eliminate deadly and debilitating diseases.

The Carters were among my first and most inspiring role models in global health. Over time, we became good friends. They played a pretty profound role in the early days of the Gates Foundation. I’m especially grateful that they introduced us to Dr. Bill Foege, who once helped eradicate smallpox and was a key advisor for our global health work.

Jimmy and Rosalynn were also good friends to my dad. One of my favorite photographs of all time shows Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela, and my dad in South Africa holding babies at a medical clinic. I remember my dad coming back from that trip with a whole new appreciation for Jimmy’s passion for helping people with HIV. At the time, then-President Thabo Mbeki was refusing to let people with HIV get treatment, and my dad watched Jimmy almost get into a fist fight with Mbeki over the issue. As Jimmy said in a 2012 conversation at the Gates Foundation hosted by my dad, “He was claiming there was no relationship between HIV and AIDS and that the medicines that we were sending in, the antiretroviral medicines, were a white person’s plot to help kill black babies.” At a time when a quarter of all people in South Africa were HIV positive, Jimmy just couldn’t accept Mbeki’s obstructionism.

As with HIV, Jimmy was on the right side of history on many issues. During his childhood in rural Georgia, racial hatred was rampant, but he developed a lifelong commitment to equality and fairness. Whenever I spent time with him, I saw that commitment in action. He had a remarkable internal compass that steered him to pursue justice and equality here in America and around the world.

After Jimmy “involuntarily retired” (his term) from the White House, he reset the bar for how Presidents could use their time and influence after leaving office. When he started the Carter Center, he gave a huge shot in the arm to efforts to treat and cure diseases that rich governments were ignoring, like river blindness and Guinea worm. The latter once devastated an estimated 3.5 million people in Africa and South Asia every year. That total dropped to just 14 cases in 2023, thanks to the incredible efforts of the Carter Center.

When the world eradicates Guinea worm, it will be a testament to Jimmy’s dedication—and yet another remarkable achievement to add to his list of accomplishments. He won the United Nations Human Rights Prize and the Nobel Peace Prize. He wrote 30 books. He helped monitor more than 100 elections in countries with fragile democracies—and did not pull and punches about the ways America’s own democracy was being undermined from within.

He worked to erase the stigma of mental illness and improved access to care for millions of Americans. He taught at Emory University. He built hundreds of homes with Habitat for Humanity. And, as I saw when I visited with Jimmy and Rosalynn in Plains a few years ago, he also painted, built wooden furniture, and took the time to offer his intellect and wisdom to people from all walks of life. As he once told my dad, tongue in cheek, “I have Secret Service protection, so I can pretty well do what I want to!”

Whenever I have struggled with a global health challenge, I knew I could call him and ask for his candid advice. It’s just starting to sink in that I can no longer do that.

But President Carter’s example of moral leadership will inspire me for as long as I’m able to pursue philanthropy—just as it will the hundreds of millions of people whose lives he touched through peacemaking, preaching, teaching, science, and medicine. James Earl Carter Jr. was an incredible statesman and human being. I will miss him dearly.

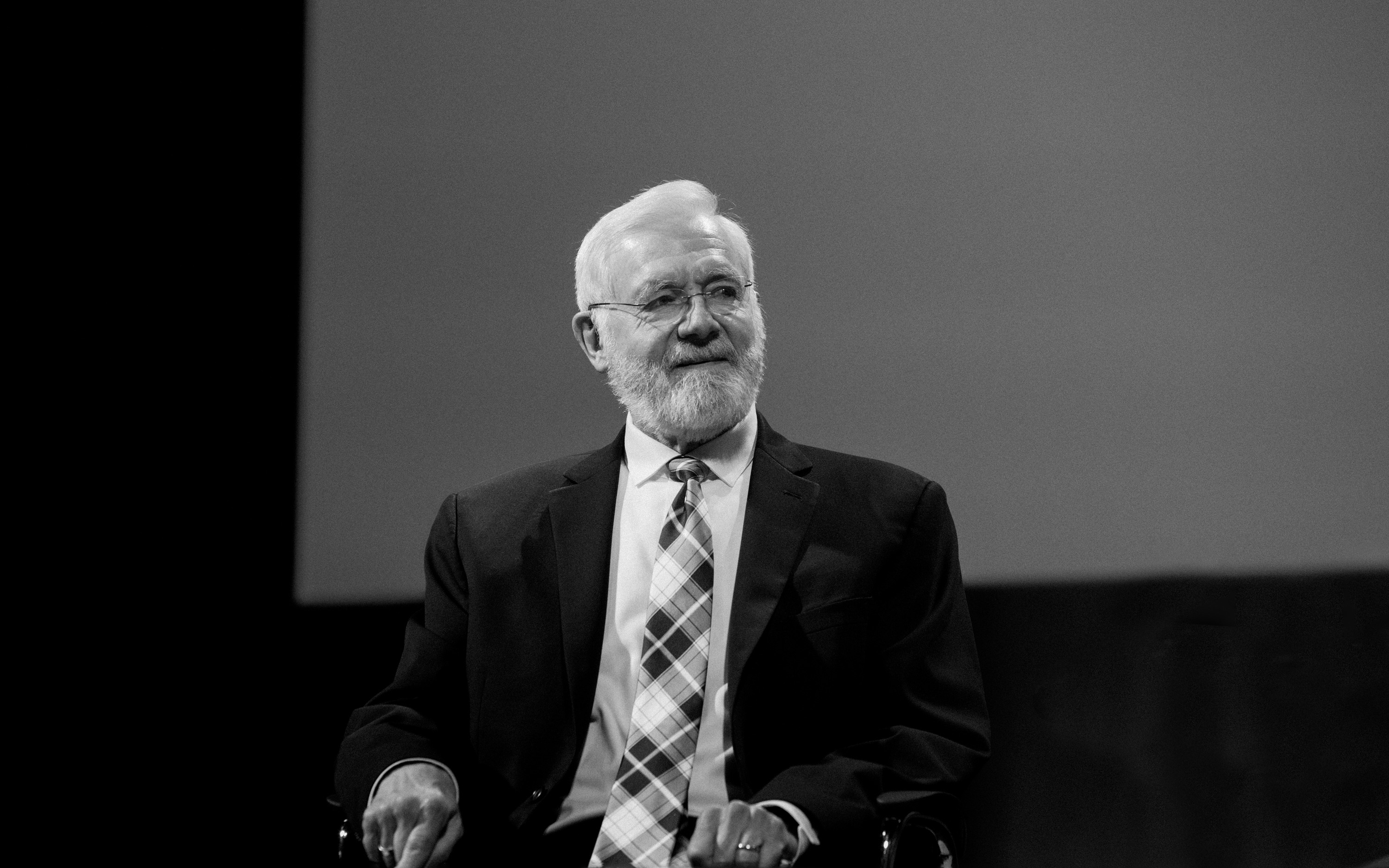

A global health giant

Dr. Bill Foege, a hero who saved hundreds of millions of lives

Celebrating the life of a mentor and friend.

I’m greatly saddened to learn of the passing of Dr. Bill Foege. Bill was a towering figure in global health—a man who saved the lives of literally hundreds of millions of people. He was also a friend and mentor who gave me a deep grounding in the history of global health and inspired me with his conviction that much more could be done to alleviate suffering.

I first met Bill in 1999. At the time, I was interested in global health but didn’t know much about it. Soon after, we asked Bill to join the Gates Foundation as a senior advisor. In doing so, we used the oldest trick in the leadership handbook: get people who know more than you do to join your team.

It was obvious right away that Bill was a special person—not just because he was so accomplished but also because of his compassion for humanity. In that way, he reminded me of my dad.

Bill loved to send me books to help me educate myself about global health. In fact, right after we met for the first time, Bill followed up by sending me a list of 82 books and articles.

One of those books was Out of My Life and Thought, the autobiography of the global health pioneer Albert Schweitzer. “Fortunate are those who succeed in giving themselves genuinely and completely,” Schweitzer wrote in 1933. “[But] anyone who proposes to do good must not expect people to roll any stones out of his way, and must calmly accept his lot even if they roll a few more into it. Only force that in the face of obstacles becomes stronger can win.” That passage perfectly describes Bill and his willingness to do whatever it took to help the world’s poorest people.

Bill read Schweitzer’s book as a teenager growing up in rural eastern Washington, and it helped inspire him to dedicate his life to global health. When Bill attended medical school, the field of global health was sorely neglected. “At my fiftieth medical school class reunion, a classmate confessed that when I told him I wanted to go into global health, he said to himself, What a waste,” Bill wrote in his book The Fears of the Rich, the Needs of the Poor. And then Bill helped invigorate that neglected field.

He was best known for the strategy and leadership that helped the world eradicate smallpox, one of the most important victories in the history of public health. That success brought an end to a horrific disease that killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone. It also gave the world the confidence to try to eradicate polio, Guinea worm, measles, malaria, and other diseases.

Bill sometimes put his own life at risk to do his work. While fighting smallpox outbreaks during the Nigerian civil war, he was arrested and held in prison twice— “not a sought-after experience,” he wrote with his usual understatement. “But interestingly, my concern at the moment was for the time being lost for planning Monday’s [vaccination efforts].”

I had long known about his accomplishments as director of the Centers for Disease Control, but reading The Fears of the Rich, the Needs of the Poor gave me a deep understanding of the constant political and policy battles he had to fight during these years. “Reason was [often] brushed aside,” he wrote. “The power of science is often neutralized by the power of power.” Bill showed tremendous patience and moral courage in fighting for what he believed in.

When I first met Bill, I was also blown away by what he had done to expand vaccination for the world’s poorest children. He was instrumental in launching the Task Force for Child Survival, which quadrupled the percentage of children around the world who receive basic vaccinations. He also used his positions at the task force and as director of the Carter Center to help deliver a miracle drug called Mectizan to tens of millions of people a year suffering from a debilitating disease called onchocerciasis. Very few other people could have brought together such a diverse coalition of partners—including African health ministers, nonprofits, churches, and a major pharmaceutical company. Bill told that story in an essay that he let me share on Gates Notes in 2014. It is an amazing piece of writing and gives you a sense of the kind of person he was.

I also want people to know how humble Bill was. One of my favorite examples comes from the final days of the push to eradicate smallpox, when he and his family decided to return to the U.S. from India. His boss at the time urged Bill to remain in India until he and his team could celebrate the world’s final case of smallpox. Bill told his boss, “If I remain in India, too much attention would be directed toward the external support that India received, and it is very important that recognition be given to the accomplishments of hundreds of thousands of Indians who really did the work.”

Late in life, Bill spoke openly about his own mortality. “I feel so enthusiastic every day about seeing the newest thing in science and health,” he told an interviewer. “The part that’s going to be hard about dying is not dying but not being able to see what’s happening next.” The legacy of Bill’s career is that many of the remarkable developments to come will have his imprint all over them.

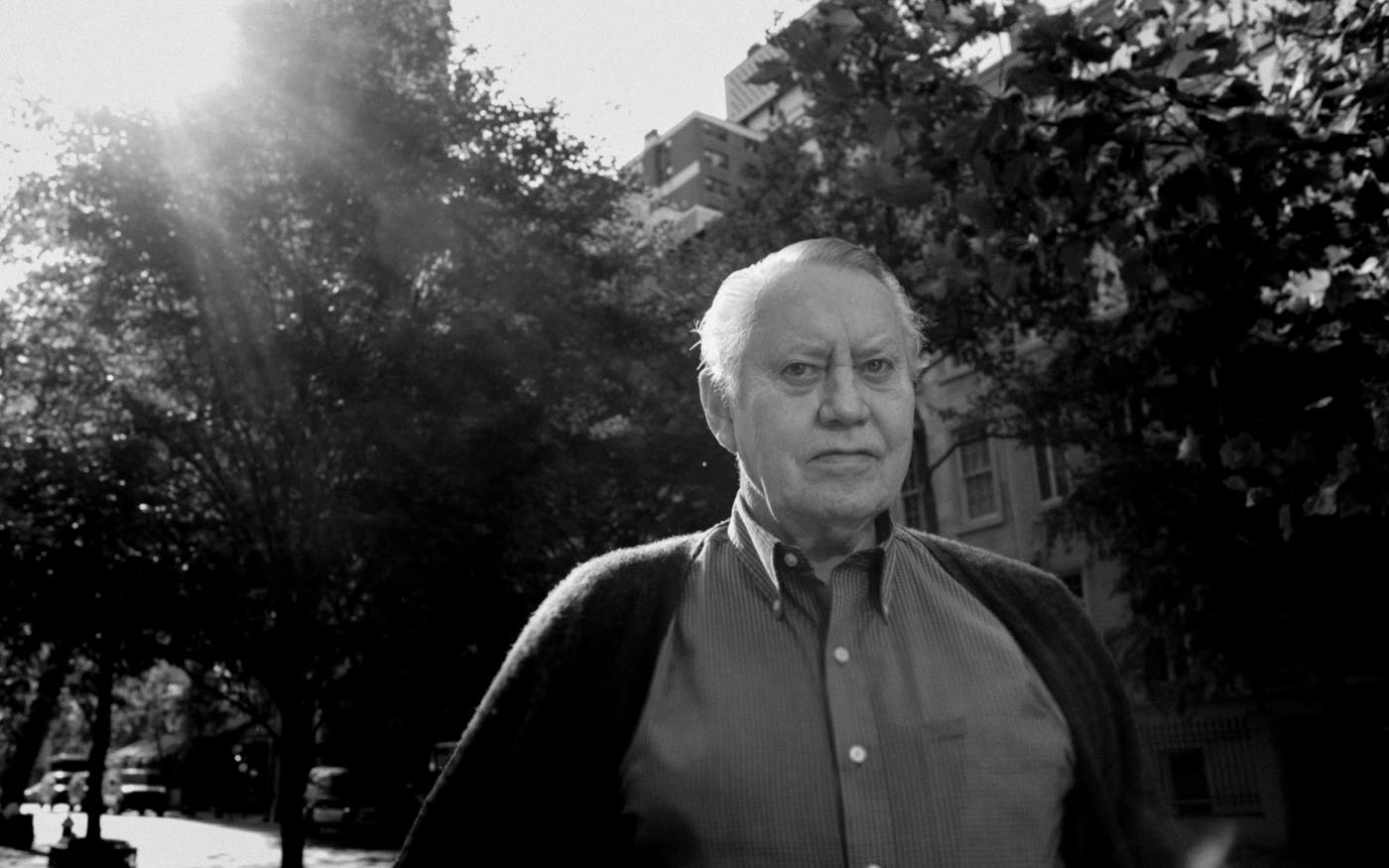

Goodbye

Remembering my father

I will miss my dad every day.

My dad passed away peacefully at home yesterday, surrounded by his family.

We will miss him more than we can express right now. We are feeling grief but also gratitude. My dad’s passing was not unexpected—he was 94 years old and his health had been declining—so we have all had a long time to reflect on just how lucky we are to have had this amazing man in our lives for so many years. And we are not alone in these feelings. My dad’s wisdom, generosity, empathy, and humility had a huge influence on people around the world.

My sisters, Kristi and Libby, and I are very lucky to have been raised by our mom and dad. They gave us constant encouragement and were always patient with us. I knew their love and support were unconditional, even when we clashed in my teenage years. I am sure that’s one of the reasons why I felt comfortable taking some big risks when I was young, like leaving college to start Microsoft with Paul Allen. I knew they would be in my corner even if I failed.

As I got older, I came to appreciate my dad’s quiet influence on almost everything I have done in life. In Microsoft’s early years, I turned to him at key moments to seek his legal counsel. (Incidentally, my dad played a similar role for Howard Schultz of Starbucks, helping him out at a key juncture in his business life. I suspect there are many others who have similar stories.)

My dad also had a profound influence on my drive. When I was a kid, he wasn’t prescriptive or domineering, and yet he never let me coast along at things I was good at, and he always pushed me to try things I hated or didn’t think I could do (swimming and soccer, for example). And he modeled an amazing work ethic. He was one of the hardest-working and most respected lawyers in Seattle, as well as a major civic leader in our region.

My dad’s influence on our philanthropy was just as big. Throughout my childhood, he and my mom taught me by example what generosity looked like in how they used their time and resources. One night in the 1990s, before we started our foundation, Melinda, Dad, and I were standing in line at the movies. Melinda and I were talking about how we had been getting more requests for donations in the mail. Dad simply said, “Maybe I can help.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation would not be what it is today without my dad. More than anyone else, he shaped the values of the foundation. He was collaborative, judicious, and serious about learning. He was dignified but hated anything that seemed pretentious. (Dad’s given name was William H. Gates II, but he never used the “II”—he thought it sounded stuffy.) He was great at stepping back and seeing the big picture. He was quick to tear up when he saw people suffering in the world. And he would not let any of us forget the people behind the strategies we were discussing.

People who came through the doors of the Gates Foundation felt honored to work with my dad. He saw the best in everyone and made everyone feel special.

We worked together at the foundation not so much as father and son but as friends and colleagues. He and I had always wanted to do something concrete together. When we started doing so in a big way at the foundation, we had no idea how much fun we would have. We only grew closer during more than two decades of working together.

Finally, my dad had a profoundly positive influence on my most important roles—husband and father. When I am at my best, I know it is because of what I learned from my dad about respecting women, honoring individuality, and guiding children’s choices with love and respect.

Dad wrote me a letter on my 50th birthday. It is one of my most prized possessions. In it, he encouraged me to stay curious. He said some very touching things about how much he loved being a father to my sisters and me. “Over time,” he wrote, “I have cautioned you and others about the overuse of the adjective ‘incredible’ to apply to facts that were short of meeting its high standard. This is a word with huge meaning to be used only in extraordinary settings. What I want to say, here, is simply that the experience of being your father has been… incredible.”

I know he would not want me to overuse the word, but there is no danger of doing that now. The experience of being the son of Bill Gates was incredible. People used to ask my dad if he was the real Bill Gates. The truth is, he was everything I try to be. I will miss him every day.

My family worked together on a wonderful obituary for my dad, which you can read here.

A true hero

Paul Farmer’s legacy is the lives he saved

I have never known anyone who was more passionate about reducing the world’s worst inequities in health.

When I found out yesterday morning that Paul Farmer had died, I thought first of his wife, Didi, and their three children. I thought of his colleagues, and of everyone whose life was saved or changed for the better by him. And then I thought of all the people who know and care about global health because of Paul, far too many to count.

Paul is a hero, and I was fortunate to call him a friend. Although we crossed paths at various conferences over the years, the first time I really got to hang out with him was during a trip to Cange, a small town in central Haiti, with Melinda in 2005. We were there to visit a health clinic run by Partners in Health, the incredible organization that Paul co-founded (and that our foundation is proud to support). At the time, PIH was providing world-class healthcare to people in Haiti, Peru, and Russia, although it’s since expanded to eight more countries.

I’ve visited a lot of rural health clinics through my work with the foundation. I’m always blown away by the remarkable and dedicated people working at them, but Paul was special even among such peers.

He was able to connect with his patients in a way that would be exceptional for any doctor, but was especially so for a gangly white guy from the Berkshires working in rural Haiti. He was a teacher who loved educating his students, whether they were future doctors studying at Harvard Medical School or community health workers-in-training at one of PIH’s clinics. But the thing that always stood out to me most about Paul was his single-minded focus on helping people in the world’s poorest countries.

In Tracy Kidder’s book Mountains Beyond Mountains—which I can’t recommend highly enough if you want to learn more about Paul’s career—there’s a story about a young child whom Paul and his team treated for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru. After the boy was discharged from the hospital, his mother approached Paul to thank him as he was getting into his car to head home. Paul responded in Spanish, “For me, it is a privilege.”

He was never happier than when he was caring for patients in one of the clinics he helped create. I have never known anyone who was more passionate about reducing the world’s worst inequities in health—or who did more to live by his values.

Even as Paul’s reputation as a global health hero grew, his focus never wavered from helping people directly on the ground. He was a humble man who never had any interest in seeking attention unless it would make life better for the people he served. I remember meeting with one of his patients during that first visit to Haiti. The woman spoke Creole, so Paul had to translate for us. At one point, she launched into what was clearly a long story about him—I could hear the words “Doktè Paul” mentioned several times. When she finished, I turned to Paul and asked what she had said. He sheepishly replied, “Just some obligatory praise for me.”

The only time Paul sought the spotlight was when he knew he had an opportunity to highlight inequality and speak to the next generation of global health leaders. He gave many commencement addresses over the years, and I suspect he’s the reason a lot of young people have entered careers in public health. He is one of the most inspirational people I’ve ever met. His ability to inspire was one of the reasons why, when Melinda and I went back to visit Paul in Haiti in 2014, we brought our children with us.

Although his work was his life’s joy, he was a wonderful person to be around when he was off the clock, too. I have fond memories of visiting his modest house in Haiti, which had a lovely garden that he was proud of. One of my favorite Paul stories happened when I traveled to visit PIH’s facilities in Rwanda. After our meetings were done, we decided to visit the mountains nearby to see the gorillas—but Paul hadn’t brought a change of clothes with him. I’ll never forget the image of Paul trekking up the steep misty hillside wearing a suit and tie.

There will never be another Paul Farmer, and I will miss him deeply. I am comforted by the knowledge that his influence will be felt for decades to come. His work will continue through Partners in Health, and it will be carried on by the many people he trained and inspired.

At the end of the day, though, Paul’s most lasting impact can be found in the patients he loved so dearly—all of the mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters who are alive today because Paul dedicated his life to helping them.

I can’t imagine a more phenomenal legacy.

This article originally appeared in The Atlantic.

…and many more

Happy 90th, Warren!

It’s hard to believe Warren Buffett is entering his tenth decade.

Warren Buffett turns 90 years old today. It’s hard to believe that my close friend is entering his tenth decade. Warren has the mental sharpness of a 30-year-old, the mischievous laugh of a 10-year-old, and the diet of a 6-year-old. He once told me that he looked at the data and discovered that first-graders have the best actuarial odds, so he decided to eat like one. He was only half-joking.

Here’s a short birthday video in honor of his dietary preferences:

Warren is still so youthful that it’s easy to forget he was once an actual young man, just starting out in his career. Here he is with his first wife, Susan, and their first two children, Susie and Howard. (Peter hadn’t been born yet.) This photo was taken in 1956, around the time Warren started the Buffett Partnership, the investment firm that eventually morphed into Berkshire Hathaway.

Upsidedownright

Grilling and chilling with Warren

Learn what Warren Buffett and a Dairy Queen Blizzard have in common.

If you’ve ever been to a Dairy Queen, you’re probably familiar with one of their most popular menu items, the Blizzard, soft serve ice cream mixed with sundae toppings, cookies, brownies, or candy. You might also be aware that every Blizzard is served upside down—a surprising piece of fast food performance art to prove that each treat is so thick it will defy gravity.

“Thinking differently and celebrating an upside-down philosophy runs deep in the DQ system,” is how one Dairy Queen executive once explained the practice.

The same could be said of the genius of Dairy Queen’s owner, Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway empire acquired the restaurant chain in 1998. (A frequent Dairy Queen customer, Warren explained at the time that he and his business partner, Charlie Munger, “put our money where our mouth is.”)

Every time I get to see Warren, I’m struck by his surprising, insightful, “upside-down” view of the world. He thinks differently—about almost everything. For starters, he credits his amazing success to something anyone could do. “I just sit in my office and read all day,” he explained.

In a time when instant gratification is craved in all aspects of life, Warren is one of the most patient people I know, willing to wait to get the results he wants. As he once said, “Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

And, as I’ve learned again and again during my visits with him even his diet is oddly upside down. Instead of ending his day with dessert, that’s how he likes to begin the day. He counts Oreos and ice cream among his breakfast foods!

During my visit to Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting in Omaha last month, I learned more about Warren’s sweet tooth. Warren and I broke away from the meetings to visit a Dairy Queen for some lunch and to get some restaurant training. We learned how to work the cash register, greet guests, and make a Blizzard (including the proper way to serve it, “Always upside down with a smile!”) I think I may have been a quicker study than Warren in the Blizzard department but watch the video above and you can judge for yourself.

Now that Warren knows how to make a Blizzard, I suspect it will be on his breakfast menu too. (Warren, just be careful turning it upside down!)

Sweet emotion

Warren and I visited a fantastic candy store in Omaha

And had a blast.

Whenever I hang out with Warren Buffett, I feel like a kid in a candy store. And not just because of his famous sweet tooth (one of the first times he came to visit in Seattle, our kids were stunned when they saw him chowing down Oreos for breakfast). We’ve been close friends for more than 25 years, and we have just as much fun together now as we did when we first met. In all that time we have never run out of things to talk about and laugh about.

So when we got together in Omaha during this year’s Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, we decided to check out a real candy store. Actually, although the Fairmont Antiques & Mercantile has just about every kind of sweet you can imagine, it is much more than a candy store. It’s also an old-fashioned soda shop, used record store, vintage memorabilia shop, and pinball museum. We had a blast reminiscing about our favorite treats, Melinda’s and my special history with Willie Nelson, why pinball machines were the best business Warren ever had, and a lot more. Take a look:

A War on Twaddle

Remembering David MacKay

He was committed to clear thinking about clean energy.

I was sad to learn last month that David MacKay had died of cancer. He was just 48 years old. David was well known among those who study clean energy, and he had a big influence on a lot of people, including me. But if you don’t follow the issue closely, you may not have heard of him. So I want to take a minute to tell you about David and his work.

I discovered David through his eye-opening book Sustainable Energy—Without the Hot Air. He was a physicist at Cambridge University, and his goal was to, as he put it, cut “UK emissions of twaddle” by helping people think more rigorously and numerically about clean energy. His book doesn’t favor one zero-carbon solution over another. He just shows you how to do the math for yourself, so you can work out the answers to big questions like “how much carbon do cars emit?” and “how much energy can we expect to get from renewable sources?”

Sustainable Energy really shaped my thinking. A few years ago, when I gave a TED talk on energy, I bought 2,000 copies to pass out to everyone in the audience. To this day, if you want to understand the opportunities for clean energy, nothing else comes close. I still go back and re-read parts of it myself.

Revisiting his work will be a bittersweet experience now. I had the pleasure of getting to know David and learning from him. He was always generous with his time, and he was just as thoughtful and unassuming in person as he was in writing. (Although he was a knight, he never went by Sir David.) He also inspired colleagues to take on related topics with the same rigor and sense of fun. One group of Cambridge researchers followed his lead with the excellent Sustainable Materials With Both Eyes Open.

David made Sustainable Energy—Without the Hot Air available as a free download. He also gave a very good TED talk on clean energy. If you are at all interested in the topic, I strongly encourage you to take a look at the book and the talk. You will not find a more generous and engaging guide to energy than David MacKay. I will miss him a lot, but I am grateful that he left behind so much fantastic work. It is a fitting legacy.

Update: This post has been edited to fix an error. David was knighted this year, not years ago.

The secret billionaire

Chuck Feeney was one of the greatest philanthropists ever

I’m grateful that I got to learn from him.

I was very sad to hear about the passing of Chuck Feeney. He was one of my personal heroes and one of the greatest philanthropists of all time.

Chuck had four important traits that made him so special.

First, he was totally dedicated to giving away everything he had. In the 1980s, at the height of his entrepreneurial success, he gave his entire stake in his company to his foundation and then spent the next 32 years awarding all of that money to nonprofits around the world. He and his foundation helped build more than 1,000 buildings across five continents, and yet Chuck decided he didn’t even need to own a home. After giving away his $8 billion fortune, he and his wife lived in a rented apartment.

Second, Chuck started humble and stayed humble. He was born during the Depression and had a very modest upbringing in New Jersey. He went to college on the G.I. Bill after serving as an Army radio operator during the Korean War. Once his wealth enabled him to start giving away huge sums of money, he insisted on doing so without any publicity; his giving was strictly anonymous until his identity was revealed in 1997. Chuck wanted to give away his entire $8 billion fortune without anyone outside his immediate circle knowing.

Third, he was passionate about philanthropy. I’m sure he felt pride at what he created in his business life, including not only Duty Free Shoppers but also the investment firm General Atlantic Partners. But I know he got a lot of personal satisfaction helping solve big social problems around the world. He loved meeting people, learning about issues, and thinking about the best ways to help out with his time, knowledge, and money.

Fourth, as a result of all of the above, he was a very effective philanthropist. He had a major hand in bringing about the Irish Republican Army ceasefire in 1994 and the historic peace agreement in Northern Ireland. His “big bets” helped rebuild Vietnam’s primary health care system for the benefit of millions of rural families. In education and health care, he helped his grantees build strong institutions that will produce meaningful, measurable change for many years.

I had the honor of meeting Chuck at the time Melinda, Warren, and I were starting to think about launching the Giving Pledge. We were blown away by how approachable he was. And we could tell immediately that Chuck really enjoyed giving. As he later put it when he joined the Giving Pledge, “I cannot think of a more personally rewarding and appropriate use of wealth than to give while one is living—to personally devote oneself to meaningful efforts to improve the human condition.”

Despite his soft-spoken nature and desire for anonymity, he was always glad to talk about what he was learning in the hope of helping others find the same joy and impact that he did. As a result, he had a very positive influence on many other givers. He inspired others to think about the merits of spending down a foundation’s assets, or as he put it, “giving while living.” He helped donors see how rewarding it was to get deeply and personally involved. His bold stand on HIV encouraged others to support advocacy.

I’m grateful to have known and learned from Chuck. His remarkable legacy will live on for generations to come, through all of the organizations he strengthened and all the ways he influenced others to give of their fortunes and of themselves.

A Girl’s Effect

Meeting Malala

My conversation with the Nobel Prize winner about her amazing work.

Two weeks ago, I had a big honor. I got to spend some time in New York with Malala Yousafzai, one of the most courageous people I’ve ever met.

As I’m sure you know, Malala is the Pakistani teenager who was shot by a Talib gunman for her belief that all girls should be able to go to school. After meeting her, I can tell you that there is much more to Malala than the story of a brutal shooting and a miraculous recovery. She’s a really impressive person and a compelling, sophisticated advocate. I loved chatting with her and just wish the conversation could have gone on longer.

Even though she nearly died, will have lifelong physical challenges, and is living in exile in England, she harbors no ill will toward the man who shot her. Rather than dwelling in a place of anger or fear, she’s sweet and funny. And even more impressive, she has managed to keep her feet on the ground despite the rush of attention she has gotten since she became the youngest Nobel laureate in history and, as New York Times columnist Nick Kristof wrote, “perhaps the most visible teenage girl in the world.”

That humility is a good thing because her visibility is about to increase yet again. The Academy Award–winning filmmaker Davis Guggenheim, who spent the better part of a year living and traveling with Malala and her family, has just released his feature-length documentary He Named Me Malala. (Full disclosure: Davis Guggenheim is a friend of mine.)

I recently had a chance to see the movie with Phoebe, my 13-year-old daughter, and a friend of hers. I thought the movie was great. And so did Phoebe. She was truly inspired by Malala and her mission to make sure all girls can get a high-quality education. Keep in mind that Phoebe is already quite connected with the issue of girls’ education, in part because she got to spend ten days last summer as an assistant teacher in a primary school in Rwanda. But I believe that most people her age and older who see this movie will be compelled by the story and how well Davis tells it.

I loved how we see Malala flying around the world defending life, liberty, and the pursuit of education one day and the next being a normal teenager struggling with homework and her brothers. I also loved the visually stunning animated sequences that bring the backstory to life.

I was most compelled by the film’s exploration of how Malala’s father, Ziauddin, encouraged his daughter to find her voice and speak out with courage, as he wished he could have done earlier in his own life. Malala made it clear in the movie and in my conversation with her that she does not believe her father pushed her onto her life path or put her in harm’s way. But I suspect the movie will spark a lot of provocative conversations among parents about risk-taking, moral courage, and how we shape our children to stand up for what’s right.

I’m quite sure that most moviegoers will leave the theater feeling far more hope than grief—just like Malala herself. And they’ll probably ask the same question Phoebe asked me: “How can I help?”

I think Davis accomplished exactly what he set out to do. Despite having to overcome the “spoiler-alert” challenge of telling a story whose ending we already know, he grabs us by the lapels and motivates us to act. Personally, I’ll be looking for ways our foundation can help Malala use that magnificent voice of hers to the best possible effect.

Data master

Our memories of Hans Rosling

Remembering a wonderful friend, teacher, and champion for the poorest.

We are sad to report that Hans Rosling, a friend and teacher we both admired a great deal, died February 7. He was 68 years old.

Like many people, we first became aware of Hans when he gave a mind-blowing TED talk in 2006. He had spent decades working in public health, with a focus on poor countries, and he used his talk to share some surprising facts about how life is getting better, even for the world’s poorest.

We loved his message, but even more, we loved the way he delivered it. (We weren’t alone: That talk has been viewed more than 11 million times.) We had been trying without much luck to explain some of the same ideas, and Hans found a breakthrough way to make them clear and compelling. He could make you laugh and get you excited about the subject, while explaining something super-important. It was magical.

Later, we got to know Hans and his family personally, and we discovered that off-stage, Hans was pretty much the same person. Having dinner with him was every bit as fun and inspiring as watching him lecture.

In the last year of his life, Hans sent us a very touching letter. He told us that he had cancer, and then he made a request. He wasn’t asking for any personal favors. He simply hoped that we would promise to keep spreading the message he was so passionate about: that the world is making progress, and that policy decisions should be grounded in data. Of course we were happy to make that pledge. Hans was a great champion for the world’s poorest, and for clear thinking. He was also a wonderful man and we will miss him a lot.

If you want to know more about Hans and his work, we recommend this short article in Nature, any one of his many TED talks, and any of the many videos he posted on his Gapminder site.

Fighting Blindness

A story from one of my heroes

How a global coalition came together to curb a crippling disease.

Bill Foege is one of my heroes. He’s a giant in the field of global health, having devised the strategy that led to the eradication of smallpox (among many other accomplishments). Melinda and I are very lucky that he has been an adviser to us since the early days of our health work.

Bill is not only a great thinker and doer, he is also a great writer. He recently sent Melinda and me a fascinating note about his experience working to save children’s lives with vaccines and medicine in the 1980s and ’90s. The whole thing is too long to post here, but I want to share this excerpt with you.

It’s the story of how a coalition came together to fight a debilitating disease called river blindness (or onchocerciasis), which is caused by a parasitic worm and was one of the leading causes of blindness in poor countries. The coalition set out to deliver a drug called Mectizan, which was made by the pharmaceutical company Merck, to everyone who needed it. In Bill’s telling, the story is filled with twists and turns, and success was hardly preordained.

Bill’s note captures the power of partnerships to improve health for the poorest people in the world. It is also a good account of all the logistical details required to pull off an ambitious goal. And it is a vivid reminder of why Melinda and I love what we do. I hope you find this story as instructive and inspiring as I do.

It starts in 1997, after the Mectizan program has been in place for several years…

Bill Foege writes:

In November 1997, I visited a village in Mali and sat with a gathering of village residents on benches that had been pulled together for the meeting. One bench was for blind people. And there was one young man, only 39 years of age, who had been blind for 21 years! Blind for over half of his life! The people in that village were very sophisticated about onchocerciasis. They knew that their children would never have to put up with this cause of blindness, and they were grateful. The visit helped those of us who spend time in meetings, thinking about policy, or writing papers. It helped us to be grounded, to see the impact of the Mectizan program on people. But it was also a chance for the villagers to become connected, to see Merck employees and to know that medicine doesn’t just appear in a village by magic. They saw the faces of people who spend their days worrying about schedules and customs, about dosage and packaging, about storage and records. We were reminded that we live in an interdependent world where it takes the whole world to raise a healthy child!

What led up to that meeting in Mali? And where does one start? History is always a book that we begin in the middle; however, we must begin someplace. It was in 1893 that onchocerciasis was first described. It was in 1926 that the life cycle was finally understood. And it was in 1974 that the Onchocerciasis Control Program was established by World Health Organization (WHO). That is a story in itself.

But the story took a leap forward in 1978, when Merck researcher William Campbell went to see Roy Vagelos, head of the Merck Research Labs, with the idea that ivermectin, being used to prevent heartworm in dogs, might have an impact on onchocerciasis in humans. It would take millions of dollars to determine if that was true… and the potential market was small. Roy Vagelos decided to approve the proposal.

It is hard to reconstruct the ethos of this company, where the founders’ son, George Merck, declared, “We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for profits, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear.” Add to that Roy Vagelos and you have an understanding of what followed.

In February 1981, the first human tests were conducted at the University of Dakar. By 1983, the results were so encouraging that Phase II studies began and by 1986 Phase III studies on 1,200 patients in Ghana and Liberia had determined optimal dosing. In 1987 papers were filed in France for regulatory approval.

Roy Vagelos tried to find a way to distribute the drug. He went to WHO and found himself overwhelmed by the bureaucracy, then to USAID. USAID was not interested. On Oct. 21, 1987, at press conferences in Washington and Paris, Merck said it would supply Mectizan, for the treatment of river blindness, to everyone who needed it, for as long as necessary, at no charge.

That is as important in the history of global health as the breaching of the Berlin Wall was to democracy. John Maynard Keynes once said, “The day is not far off when the economic problems will take a back seat to our real problems.” He was talking about human relations, behavior, health, and religion. Maybe Oct. 21, 1987 was that day. The moment when a corporation had the audacity to make social need more important than profits. To make a commitment that went beyond what could actually be seen. To treat anyone free, as long as required.

Merck came to the Task Force for Child Survival [a group Foege was working with—ed.] and made the same offer they had made to WHO and USAID. If they gave the drug free, would we figure out a way to distribute it?

The Mectizan Expert Committee was formed in 1988 to provide a mechanism to make Mectizan available for community use to any applicant who could show they would get the drug to the right people, in the right amounts, that the drug would not be diverted to the marketplace, and that all applications would be approved by the Ministry of Health of their country so that we could have total transparency with the government. I chaired that committee for 12 years and the Task Force hired a few people to run the program.

I believe in a cause and effect world rather than a world of magic. And yet that doesn’t keep me from being filled with awe at the inspirational and even miraculous ingredients of this program.

The birth of the drug involved a soil sample taken from a golf course in Japan, the scientific facilities and managerial abilities of Merck in the United States, the obsession and zeal of a researcher named Mohammad Aziz (a product of the Indian subcontinent), field trials involving people and sites in Africa, and finally, regulatory approval by France. This is a global story.

We saw a magical coalition for Mectizan. It started quite small, including a few people on the Mectizan Expert Committee, the group interested at Merck, and the Onchocerciasis Control Program in West Africa. But it grew. As church-sponsored medical mission groups found they could get Mectizan, but only if they applied through the Ministry of Health to the committee, they worked with governments, and a widening coalition developed. And soon even the World Bank was involved in developing a fund for Mectizan distribution.

So the gift, in turn, was amplified by a coalition of global organizations, ministries of health, foundations, mission groups, community organizations, and volunteers, all held together by a shared goal rather than a true organizational structure.

Then there is the miracle of Mectizan delivery. We originally hoped to reach 6 million people in six years. We did it in four. When President Carter got involved, the distribution increased rapidly. He would talk to Heads of State in Africa and they would find an interest in the disease. If they were interested, one could depend on their Ministers of Health to become interested. Soon the program was reaching 10 million, then 20 million a year. Each person was at the end of a delivery system that included:

- Applications requiring mail, telephone, fax, and computers,

- A secretariat and committee,

- Orders placed and sorted in New Jersey,

- Tablets bottled, boxed, and shipped from France,

- Airlines and Customs,

- Storage and delivery,

- A pipeline that branches into thousands of spigots,

- Clinics, mobile teams, village workers, drivers, enumerators, and scribes,

- Dirt roads, flooded rivers, war and conflict, and every ample barrier that Africa has to offer in reaching its poor.

Millions of separate stories, with millions of people playing supporting roles… and yet despite the odds, it actually works! We can never become too jaded to simply be amazed at what a coalition can do.

Blindness has decreased, transmission rates are being reduced, and we can even dream of a time when onchocerciasis is but a memory, a footnote in medical texts, a curiosity in the oral history of a village.

There is a metal sculpture commissioned by John Moores, one of the outstanding warriors in the battle against onchocerciasis. The sculpture shows the familiar figure of a small boy, investing in the future of his African village by guiding a blind man with a stick. The original of this sculpture was dedicated in the Merck headquarters’s lobby. It doesn’t highlight the most clever product of Merck, the most profitable product, or the most scientifically advanced example of the company. Instead, it is a monument to human and corporate decency.

There are also copies of this statue at the Carter Center, the World Bank, and WHO headquarters, serving as a symbol of hope in the midst of world problems… a statement that individuals can make a difference… and a reminder that we can mobilize the riches of the world to improve the health of the poorest of the poor.

Farewell, Madiba

Remembering Nelson Mandela

Melinda and I admired Nelson Mandela for his courage.

Melinda and I admired Nelson Mandela, as the world did, for his courageous stand against apartheid. But we came to know him personally for a different reason: the fight against HIV/AIDS.

He was especially powerful in speaking out against stigma. In many countries, especially in the early years of the HIV epidemic, there was a lot of misinformation about how the virus was passed. Some people were afraid to touch a person with HIV.

President Mandela knew how damaging that was. He knew it made fighting the epidemic harder, and it wrecked the lives of people suffering from the disease. He also knew the stigma was just based on fear and ignorance. He thought he could make a difference by teaching people the facts.

This was something we talked about a lot every time we met: How could we fight stigma and spread reliable information about the disease?

You can see the power of his example in one of my favorite photographs ever. My dad went to visit him in South Africa along with President Jimmy Carter. President Mandela took them to a clinic that cared for infants born with HIV. As reporters and photographers looked on, he picked up one of the babies and held it in his arms. President Carter and my dad did the same. The next day, the image of all three men cradling HIV-positive babies was broadcast throughout South Africa.

It sent a powerful message: that people did not need to be afraid of touching a person with HIV.

It was just one small step, and we still have a long way to go in the fight against AIDS. But Nelson Mandela played a crucial role in the progress we have made so far. I will never forget the example that he set.